Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Baseline-Assessments for Wind Energy Projects

The Clean Development Mechanism

In the Kyoto Protocol the industrialised countries committed themselves to binding reduction targets for greenhouse gases (GHG). In order to enable these countries to fulfil their commitment in a cost-efficient way, three flexible mechanisms - Emissions Trading (ET), Joint Implementation (JI) and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) - were developed. ET is a trade-based mechanism allowing states to buy or sell emissions rights, JI and CDM are project-based mechanisms allowing the generation of emission reductions, which are attributable to the domestic target, by investing in projects abroad.

Under the CDM, an Annex I country[1] invests in an emission-reducing project in a Non-Annex I country. These countries are also referred to as „investor country“ and „host country“. The emission reductions - the so-called certified emission reductions (CERs) - can be gained from 2000 onwards, and will be issued retrospectively as soon as the rules have been fixed and the Kyoto Protocol has come into force.

CDM requirements

For the CDM two sets of requirements exist: requirements for the participation in the mechanism in general (relating to states) and requirements for the projects (relating to the design of projects).

Regarding participation, host countries have to have ratified the Kyoto Protocol. Apart from the ratification, the investor countries have to fulfil a set of requirements relating to the estimation and reporting of domestic emissions and the booking of emission rights and certificates into a national registry.

Regarding the requirements of projects, as a technological restriction the CDM does not allow the usage of nuclear facilities. But CDM projects also have to fulfil additional requirements:

- Existing official development assistance resources must not be diverted for project financing; other public funding used for this purpose is to be separate from and not counted towards the financial obligations of the industrialised countries.

- Sustainable development: projects shall promote sustainable development in the host country. The respective requirements are specified and applied by the host country. In case of approval, the project participants are provided with a so called „letter of approval“ by the host country.

- Additionality: the emission reductions resulting from the project are to be additional to reductions which would have occurred otherwise. This requirement is checked by comparing the project emissions with the emissions of a hypothetical reference case (the "baseline") – this reference case is used to simulate the situation without the project. So determining the additionality of a project mainly depends on the choice and calculation of the baseline.

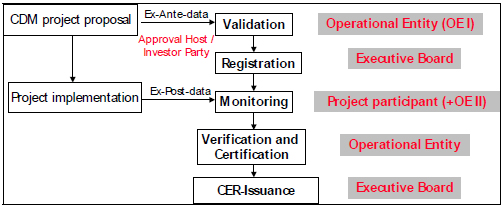

CDM project cycle

Projects wanting to qualify as CDM projects have to undergo the following project cycle:

A) Project Design: The project participants (the investor and the organisation carrying out the project) draw up a so-called project design document (PDD). An outline for such a document has already been developed by the UNFCCC.

The PDD contains

- a general as well as a technical description of the project

- the construction of the baseline and calculation of baseline emissions

- the information needed to assess the fulfilment of the CDM project requirements

- a plan for the monitoring of the project emissions

- the calculation of the project emissions.

In order to gain information about the sustainability of the project, the following activities have to be conducted:

- analysis of the environmental impacts of the project

- invitation of stakeholders’ comments. Based on the PDD, the project participants apply for the "letter of approval", to have the project recognised as a CDM project by the government of the host country. The host countries may then give their approval that the activity satisfies their sustainable development requirements.

B) Validation: the next step is the validation of the project by an appointed "Operational Entity“ (OE), which evaluates the project using the project design document with regard to the CDM criteria. OE are independent bodies which have been accredited by the "Executive Board" (EB). The EB is the central authority for the CDM, it is responsible for monitoring the CDM. It consists of 10 members (6 non-Annex I: 4 Annex-I parties) from parties to the Kyoto Protocol.

C) Registration: after a project has been validated, the documents are passed on to the EB for registration - i.e. formal acceptance as a CDM project.

D) Monitoring: subsequently, monitoring takes place. This is a task for the project participants. The verification, which takes place at regular intervals, is also conducted by an OE (different from the OE which conducted validation) which checks the accuracy of the estimated CERs ex-post. The certification involves the written assurance of the OE that the project has resulted in the verified emission reductions within a certain period. The certification report actually represents an application for the issuing of emission credits to the amount of the verified emission reductions. The EB issues the CERs, unless there is an application submitted by a third party within a certain time to re-examine the CDM project. When issued, the CERs are individually marked with a serial number, the Share of Proceeds[2] is deducted and the remaining CERs credited to the account/s of the project participants. The CERs rewarded for a project can then be used to fulfil an emission reduction commitment or can be sold to other countries with a commitment

Calculation of emission reductions

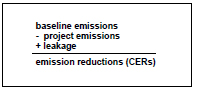

The assumption of a baseline - the amount of anthropogenic emissions which would occur if the project did not take place - is of crucial significance for the amount of credits a CDM project can generate. The amount of CERs issued for a project equals the difference between the actual emissions and the baseline. Three basic approaches are eligible for the construction of the baseline.

The most appropriate approach is to be chosen and this choice has to be explained and justified. The following approaches were developed:

- current or historical emissions,

- emissions of a technology which represents an economically attractive course of action, taking barriers to investment into account,

- average emissions of similar project activities undertaken in the previous five years, in similar social, economic, environmental and technological circumstances, and whose performance is among the top 20 percent of their category.

More detailed methodologies for the construction of the baseline are to be developed by the Executive Board in the future.

Projects can generate CERs only for a specified period, the crediting period. Participants can choose between two approaches for the crediting period:

- either a maximum of seven years which may be renewed twice at most. For each renewal an operational entity has to determine whether the baseline is still valid

- or a maximum of ten years with no option of renewal.

In order to promote small projects, simplified regulations regarding baseline construction and monitoring are applied for the following project categories:

- renewable energy project activities with a maximum output capacity of up to 15 MW,

- energy efficiency improvement project activities which reduce energy consumption, on the supply and / or demand side by up to 15 GWh per year,

- other project activities that both reduce anthropogenic emissions by sources and that directly emit less than 15 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent annually.

The simplified regulations will be worked out by the Executive Board.

When calculating the project emissions, a project boundary has to be defined, which encompasses all GHG emissions which are significant and reasonably attributable to the project and are under the control of the project participants.

If projects lead to a net change of emissions occurring outside the project boundary, this is referred to as leakage. The calculation of emission reductions incurred by the project has to be adjusted accordingly. The emission reductions attributed to a project are then calculated as follows:

Example: Preliminary CDM and Baseline-Study for the Jordan – Wind Park "Shawbak”

The CDM and Baseline study for the Shawbak wind project has been prepared by S. C. Wartmann of the German Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovations Research (ISI) for the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ).

Description of the project

- Project purpose: Construction of a privately owned 25 MW wind park at Shawbak, Jordan, to satisfy the country’s rising energy demand with a technology independent of fossil fuels.

- Project developers: The project is being developed by the GTZ on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, which was asked for assistance in developing wind power projects in Jordan by the Jordanian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources.

- Background: Electricity demand in Jordan rose at an average rate of 6.9 % p.a. from 1994-1999 and peak demand is expected to rise annually by around 4 % (with the morning demand growing stronger than the peak evening demand) between 2000-2015, with the overall demand being expected to double in this period (peak demand 1999: 1,173 MW, 2015: 2,207 MW). At present 1,540 MW are available with 66 % of this coming from steam turbine plants fired with heavy fuel oil, 30 % from gas turbines fired with diesel and natural gas, 3 % from diesel engines and 1 % from hydro and wind power. As there are currently no overcapacities in the Jordan electricity sector, generating capacities have to be expanded in order to avoid shortages in the future. The expansion plans include a 300-450 MW combined cycle power plant at Samara starting operation in 2003 at the earliest, and a 100 MW gas turbine at Rehab Power station which will be run on diesel at first and then be changed to a combined cycle plant together with an existing 100 MW gas turbine at Rehab as soon as natural gas becomes available.

Jordan is heavily dependent on fuel imports as only small resources of natural gas (5.5 billion cubic feet p.a., wells in the Risha district) and oil (600 barrels per day, Hamzeh) are available. At present, only one fourth of the existing gas turbine capacity is fired with natural gas, the rest is fired with diesel. Heavy fuel oil is imported from Iran, it is planned to import natural gas from Egypt from 2003 at the earliest. A 30-year agreement was signed in 2001, but financing for the necessary pipeline is still pending, so the start of the gas imports might be delayed. Wind power could help to decrease Jordan’s dependence on fuel imports. - Technical description of the project: The project site is located on a plateau close to King’s Highway, Shawbak. It has not been defined exactly, which part of the plateau will be designated as wind park area. On the site it is planned to erect 32-42 wind energy converters (WEC) with a capacity ranging between 600 - 800 kW[3] each, with a hub height of 50 m. Thus a capacity of approx. 25 MW will be reached. The wind park will be connected to the Jordanian grid via an 132 kV line through the substation in Rhashadiya. Due to very specific wind patterns in the eastern part of the area, electricity production for this area could not be estimated. The estimates made for the western part of the wind park area underlie uncertainties in wind behaviour patterns: the yearly electricity production (including losses, uncertainty and climatic variation) is estimated between 35,000 MWh/a (pessimistic) and 76,000 MWh/a (optimistic) with the average ranging between 51,000 and 58,000 MWh/a (this range as well depending on the types of turbines chosen).[4] The technical equipment will be imported, so the project does not aim at

technology transfer. The construction period is planned to be 1 year, the operation period 20 years. - Project boundary: The project boundary will encompass the electricity produced by the wind park excluding transmission and distribution losses. As the electricity is fed directly into the Jordanian grid, the losses suffered will be the same as for all other power plants.

- Crediting period CDM projects can receive CERs only for a defined period, the so called crediting period. A crediting period of 10 years without renewal or a crediting period of 7 years which can be renewed up to two times with a baseline review before each renewal can be chosen.

As the operational lifetime of the project will be 20 years, a renewable crediting period of 7 years – with the second crediting period also lasting 7 years and the third lasting only 6 years – is suggested. So at best CERs could be rewarded for the whole operational lifetime of the project. As the baseline will be checked and, if necessary, revised before each renewal of the crediting period, the amounts of rewarded CERs may be lower for the crediting periods 2 and 3.

Proposed baseline methodology

As mentioned before, the baseline is the level of GHG emissions against which the emission reduction incurred by the project activity is measured. Project participants have to construct the baseline according to a baseline methodology approved by the Executive Board, the supervisory authority for the Clean Development Mechanism. The simplified methodologies for small projects cannot be applied for the Aqaba wind park project, as the project capacity of 25 MW exceeds the threshold for renewable energy project activities of 15 MW. As no methodologies have been approved so far, a simple methodology was developed for this study.

Basic assumptions: The first question in baseline construction is, what would have happened without the project in question? For projects concerned with power generation this means: how would the demand satisfied by the project plants haven been met otherwise? So the question is, which power plants will the wind park replace and to which extent? These may be existing generating capacities or capacities which are considered as an alternative to the project in question. For baseline construction the following three basic baseline approaches exist:

Existing actual or historical emissions

- Emissions from a technology that represents an economically attractive course of action, taking into account barriers to investment

- the average emissions of similar project activities undertaken in the previous five years in similar social, economic, environmental and technological circumstances, and whose performance is among the top 20 per cent of their category there.

The approach deemed most appropriate has to be selected for baseline construction. The first approach is selected for the Shawbak wind park project. As the wind park output is highly dependent on the wind regime, wind independent excess capacities are needed which can substitute the capacity of the wind park in order to avoid shortages in power supply, if the wind conditions are not favourable. So as long as wind power is available, the electricity output of the conventional power plants will be decreased by the amount of electricity produced by the wind park.

In view of the dependency on wind patterns, economically more attractive wind independent plants can hardly be considered an equal alternative to the wind park, which has to be assumed when the second approach is applied. So only other wind park projects could be considered as an alternative. As wind power is an emission-free technology, baseline and project emissions would both amount to zero emissions – leading to the conclusion that wind power does not lead to emission reductions.

The third approach is based on the assumption that more advanced technologies provide for lower emissions. So this approach is only suitable for projects which actually lead to emissions – comparing the Shawbak project to another wind park (which is suitable according to the third approach)) again means comparing an emissions-free project to a zero emissions baseline.

When applying the first approach, the Shawbak project will be compared to existing generating capacities in Jordan. As the baseline will have to be estimated for up to 20 years, planned changes in the existing generating capacity have to be considered. So the baseline construction for the three crediting periods will not be based on the same assumptions.

In general, the following assumptions are made for the substitution of power from fossil fueled power plants with wind power: the electricity produced by the Shawbak wind park will replace electricity produced by other Jordanian power plants, i.e. these plants will produce less electricity. As the wind park production is dependent on the wind regime, the power plants chosen for substitution will not be shut down completely, as they have to function as back-up in case of unfavourable wind conditions. The plants preferably replaced by wind power are the ones showing comparably lower efficiency and higher fuel costs.

Table 1 shows the degrees of efficiency (MWh sent out/MWh fuel input) and other characteristics of several Jordanian power stations[5]:

References

- ↑ The countries with an emission reduction target are listed in Annex I of the Protocol and are thus referred to asfckLR„Annex I countries”, the countries without a target, the developing countries, are referred to as “Non-Annex IfckLRcountries”.

- ↑ The Share of Proceeds is a levy on the amount of CERs issued for a CDM project activity. The resources fromfckLRthis levy are to be used for two purposes: to cover the administrative costs of the CDM and to provide fundingfckLRfor the Adaptation Fund, used to finance adaptation measures for countries most affected by climate change.fckLRFor the Adaptation Fund, the levy is 2 % of the issued CERs; for the coverage of the administrative costs, afckLRpercentage still has to be fixed which will be proposed by the Executive Board.

- ↑ The calculations were conducted for four types of turbines: Enercon E40 (600 kW), Vestas V47fckLR(660 kW), Neg Micon NM 48 (750 kW), Nordex N50 (800 W).

- ↑ See MEMR(2001), p.27.

- ↑ The efficiency was calculated by applying the standardised heating values for heavy fuel oil, diesel and naturalfckLRgas to the specific fuel consumption of the power stations which were given in the DECON/NERC study, seefckLRMEMR (2001), p.14. For the conversion factors mass/volume see J.W. Rose; J.R. Cooper (1977): TechnicalfckLRData on Fuel, Istanbul; Shell; http://www.shell.ch/gas/de/fg_01.htm. For the calculations see the filefckLR“Shawbak-PDD-calculations”.