Energy Access for Displaced People

Overview

Today, more than 134 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance due to conflicts, natural disasters, and other global challenges. Among them are refugees, internally displaced people, returnees to areas rebuilding after conflict or disaster, as well as returnees settling outside their areas of origin.[1] According to the UNHCR “Global Trends” (2017)[2], 68.5 million of these people have been displaced as a result of persecution, conflict or generalized violence. In 2007, this population numbered 42.7 million. Over the last 10 years, this figure has increased by over 50%.

Access to energy is a basic human need. Energy services provide cooking, lighting, heating and clean water. In situations where large numbers of people are moving within or across borders, access to energy is a priority for basic survival. Safe and accessible fuel is needed for cooking food and to maintain suitable home temperatures. Power is needed both for lighting to provide protection and safety, as well as to support households in their economic activities and for children to study in the evening hours. Power is also needed to charge mobile phones that enable communications, which facilitates contact with family members and free flow of information. Providing energy also supports the transfer of money in cash-assistance programs.[1] Despite these needs, energy is a scarce resource in situations of displacement; the majority of displaced people do not have access to affordable, safe, reliable and clean energy. Preliminary calculations indicate that 80 % of the 8.7 million refugees and displaced people in camps have absolutely minimal access to energy, with high dependence on traditional biomass for cooking and no access to electricity[3].

Energy Access for Displaced People

This lack of access to safe and sustainable energy comes at a high cost to the health, safety and welfare of displaced people:

Health

Lack of adequate and safe energy for cooking and heating presents a serious health risk for displaced populations. Especially in countries with cold winters, heating is necessary for survival. Open fires, candles, illegal electricity connections and the use of kerosene for lighting all present serious health and safety risks. This reliance on primitive fuels (firewood, charcoal, and kerosene), is triggering respiratory and heart conditions especially in children and the elderly and is believed to be the cause of premature death for some 20,000 displaced people per year[3]. Smoke inhalation in poorly ventilated cooking areas poses a significant health risk, especially for women and children, who have the greatest exposure to indoor pollution. The children are sometimes poisoned by accidentally drinking kerosene from plastic bottles. Open fires may also lead to fire that can spread quickly in densely populated camps, resulting in severe burns or death. People’s need for energy may also force them to deploy high-risk coping strategies such as power theft. The risk of electrocution is an additional health risk to refugees and internally displaced households. Energy scarcity may also lead to malnutrition. In Chad, some 35 percent of displaced households surveyed reported skipping meals during the previous week because they lacked fuel to cook with. In Ugandan refugee camps, about half the households have admitted undercooking food more than twice a week.[3]

Security

Women and girls frequently experience intimidation and sexual violence when leaving camps to collect firewood. Within a five-month period in Sudan, some 500 displaced Darfuri women and girls were raped while collecting firewood and water (Médecins Sans Frontières, 2005). The fact that firewood collection outside camps is illegal in many countries further encourages exploitation of the vulnerable as well as the under-reporting of assaults.

Many refugee families cannot afford lighting. At night they live in darkness, using only the light of their cooking stoves. In the Dadaab camps in Kenya, 61 percent of households rely on no more than a torch for lighting.[4] Darkness facilitates violence in camps, especially against the most vulnerable members. The provision of reliable energy for lighting will result in the reduction of night-time violence. As was previously stated, the use of firewood for cooking and heating, especially in dry climates or where shelters are made of wood and textiles, leads to many fire-related accidents that can be lethal.

Environment

is a major problem in many countries containing large numbers of forcibly displaced people. An estimated 64,700 acres of forest, the equivalent of 49,000 football pitches, are burned each year by forcibly displaced families living in camps[3]. Open fires, kerosene lamps and candles cause accidental fires and generate disproportionate CO2 emissions.

According to Lahn and Grafham (2015)[3], the level of displaced people’s current energy use is economically, environmentally and socially unsustainable. Improving access to cleaner and more modern energy solutions would reduce costs, cut emissions and save lives. The EUEI PDF report on “The role of Sustainable Energy Access in the Migration Debate”[5], underlines the fact that improving energy services can have a twofold benefit, before and after migration takes place.

Before Migration

The two main reasons for migration, as directly related to energy access, are economic and environmental drivers:

Energy and Economic Migration

Economic drivers of migration, such as rural poverty, food insecurity, insufficient economic opportunities, unemployment as well as deficient healthcare and education services, are exacerbated further by a lack of energy access. The providing of energy access can improve the lives of the people in underserved communities, thus preventing some migration.

Energy and Environmental Migration

Environmental migrants are persons or groups who, for compelling reasons of sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affect their lives or living conditions, are obliged to leave their homes or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their country or abroad.[6]

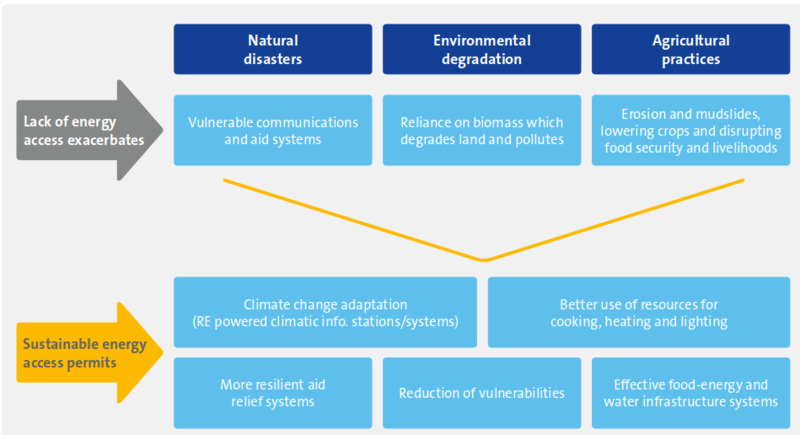

In agreement with the EUEI PDF report, the two main drivers related to environmental migration are environmental degradation and natural disasters. Progressive environmental degradation is linked to the lack of clean and sustainable fuel products for cooking, because this lack of fuel can accelerate environmental degradation; communities that rely on firewood and charcoal for cooking are directly affected by deforestation, yet at the same time contribute to it. Access to sustainable, clean energy can help the communities adapt to environmental degradation and at the same time prevent further environmental deterioration due to energy use.

Other environmental drivers of migration are natural disasters. After a disaster, clean energy technologies could provide energy for health and communication services much more rapidly than traditional generation plants[5].

Graph 1: Environmental drivers of migration, EUEI PDF report, 2017

After Migration

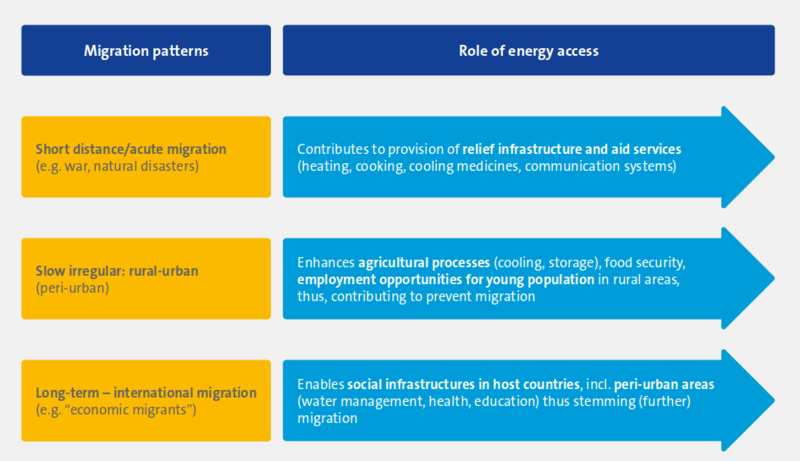

Improving energy access can increase levels of safety, comfort and economic opportunity. Additionally, it can assist with the integration of displaced populations by helping the host communities/countries cope with additional pressure on resources.

Graph 2: The role of sustainable energy access in migration patterns, EUEI PDF report, 2017

Global Plan of Action for Sustainable Energy Solutions in Situations of Displacement (GPA)

The aforesaid issues have been acknowledged and recognized by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal number 7, which aims to ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services by 2030. To this purpose, the Global Plan of Action for Sustainable Energy Solutions in Situations of Displacement (GPA)[1] was created, a framework that aims to provide concrete actions towards the vision of the United Nations’ SDG 7. According to the GPA, current energy practices in situations of displacement are often inefficient, polluting, unsafe, expensive and inadequate for displaced people and are harmful to the environment and costly to implement.

There is a need for systemic actions to mobilize resources, build capacity, raise awareness, and use the development of sustainable energy solutions to positively impact sectors such as health, protection and food security. The GPA results in a series of recommendations to address these problems. As a next step, a consultation process will be implemented to translate these recommendations into a work plan with concrete objectives, outputs and actions, to be taken in the coming 2-3 years.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Global Plan of Action for Sustainable Energy Solutions in Situations of Displacement (GPA)

- ↑ UNHCR “Global Trends” (2017), http://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2017/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Chatham House Report for the Moving Energy Initiative (2015) https://mei.chathamhouse.org/heat-light-and-power-refugees-saving-lives-reducing-costs-summary-page

- ↑ GVEP International field survey in Dadaab, Kenya, 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 EUEI PDF report on “The role of Sustainable Energy Access in the Migration Debate”, http://www.euei-pdf.org/sites/default/files/field_publication_file/the_role_of_sustainable_energy_access_in_the_migration_debate_euei_pdf_2017.pdf

- ↑ International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2014). IOM Outlook on Migration, Environment and Climate Change. http://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mecc_outlook.pdf

Further Information

- Energy Access Portal

- Figures on Energy Poverty

- Energy Access for Refugees

- Cooking Energy in Refugee Situations

- Cooking Energy in Refugee Camps- Challenges and Opportunities

- Preparation Guide for a Sustainable Energy Project in Refugee Settings

- ENERGYCoP Platform

- Energy for Displaced People - A Global Plan of Action

- A Global Plan of Action - Background, Visions and Outcomes

- The Moving Energy Initiative

- Publication - Prices, Products and Priorities: Meeting Refugees’ Energy Needs in Burkina Faso and Kenya

- Publication - Towards an holistic approach to energy access in humanitarian settings: the SET4food project from technology transfer to knowledge sharing

- Publication - Energy, Migration and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- Cooking with Clean Fuels: Designing Solutions in Kakuma Refugee Camp

|

This article is part of the Energy Access Portal which is a joint collaboration between energypedia UG and the “World Access to Modern Energy (WAME)". WAME is managed by the Museo Nazionale della Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci (MuST), the Fondazione AEM and the Florence School of Regulation (FSR) and it is supported by Fondazione CARIPLO. |

This article was written by *****.