Gender Mainstreaming in Energy - Need

Gender Mainstreaming in Mini-grid

According to the United Nations Economic and Social Council gender mainstreaming is defined as “a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design,implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated”[1].

Need for Gender Mainstreaming in Energy

Men and women access and use energy for different purposes and therefore lack of it also affects them differently[2]. This is because access to and use of energy is determined by differnet factors such as their gender roles in the society, the kind of work they do and the resources they have access to.

Understanding these gendered use/impacts of energy helps in designing sustainable energy solutions that benefit both men and women equally. Gender mainstreaming also acknowledges women’s contribution and involves them in all stages of the reneweable system design. It also helps to limit any negative impact that could occur due to the gender blind planning process and policies[3].

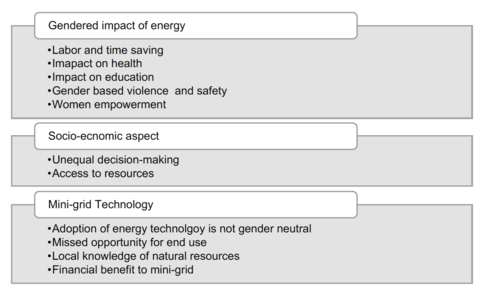

Figure 3 summarizes why gender mainstreaming is important in energy (especially for mini-grids)

Gendered Impact of Energy

Access to or lack of sustainable energy has the following gendered impact on women’s lives:

Labor and time saving: In developing countries, women and girls are mostly responsible for collecting communal resources such as firewood, water and fodder for animals. They spend about 2-20 hours per week or even more on collecting firewood and carrying it over long distances[4]. This limits the time they could have spent on other productive or leisure activities[5][6]. Furthermore, climate change impacts such as deforestation, desertification and ecosystem imbalance have worsened the situation as women now have to travel far off to collect communal resources that were previously available nearby[7].

Women in rural areas are also involved in subsistence farming and this is often laborintensive and time-consuming[6][2]. When activities such as pumping water for irrigation, grinding grains or oil pressing can be mechanized, it greatly reduces the drudgery for the women[2].

Impact on Health: In rural areas, women are the ones responsible for cooking. They use traditional fuels such as firewood, cow-dung and other biomass for cooking. Traditional cook stoves such as the three-stone fire are mostly used for cooking. These cookstoves are highly inefficient and release toxic air pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide and benzene. Since the kitchens are also poorly ventilated, women are then exposed to indoor air pollution. 2 million people worldwide, mostly women and children die each year from indoor air pollution[5][2]. The use of traditional fuels such as kerosene lamps and candles for lighting also result in fire burn and indoor air pollution[8]. As mentioned above, women have to collect and carry firewood over a long distance. Across African countries, IEA estimates that women carry fuel loads that weigh from 25 to 50 kg [9]. It is physically challenging to carry such heavy loads and result in health problems such as backache and miscarriage[10][2]. Solutions such as electric cooking could provide clean alternative to traditional fuels and reduce the burden on women. Access to electricity in hospitals is another crucial need. More than 60% of health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa do not have access to electricity and over 70% of medical devices in developing countries fail due to unreliable power supply[11]. In poor energy situations, the medical staffs also refer to flashlights or kerosene lamps for lighting. This increases the risk of giving birth at night and also affects the neo-natal care of the babies. Therefore, access to reliable electricity for health centers could greatly improve healthcare facilities[12].

Impact on education: Girls are usually responsible for helping their mothers collect firewood and also help in other labor-intensive work such as grinding or water pumping. Access to electricity results in time saving and thus frees up time which can be spent on education. Also lighting at night extends the studying hours in the evening. A study in Vietnam found out that in the newly electrified households, electrification resulted in an increase in enrollment rate for both boys and girl but it was not clear if electrification 15 had a greater impact on girls as compared to boys[13]. Gender based violence (GBV) and Safety: Women and girls usually travel to far-off distance for collecting firewood and other communal resources. Hence, they can become victims of gender-based violence or get bitten by other insects or snakes along the way or in the forest[14]. Unelectrified public spaces limit the women’s ability to go out in the evening and get involved in other income-generating activities. It also increases the crime or sexual violence faced by women in dimly lit or unelectrified spaces[15]. Thus, electrifying public spaces makes it safer for women. A study in Tunisia found that girls felt safer going to school in the morning after street lights were installed along the way to the school[16]. Electrification can also help to reduce the domestic violence within the household[16].

A study in Afghanistan found that after houses were electrified, the women reported reduced domestic violence. Previously, when the child cried in the dark, the husband would get irritated and use violence against the wife. After electrification, if the child cried at night, the women would immediately switch on the light and silent the child so that their husband would not get disturbed[17]. Another study in rural India found that television which was introduced after electrification reduced the domestic violence rate and increased the rate of girls going to school[16]. Women empowerment: Access to electricity increases the income generating opportunities for women, especially in small micro enterprise such as washing and ironing clothes, selling prepared food and beauty parlors [18][16]. A study found that access to electricity increased female employment by almost 10% in newly electrified communities in South Africa[19]. Another study in Nicaragua found that after reliable electricity, the percentage of rural women working outside increased by 23%, resulting in increased income for these households[11]. It is observed that when women received extra income, they are also most likely to invest it in the betterment of their children 16 and homes as compared to men[20]. Thus, access to increased income not only benefits the women but the entire family. Involving women in mini-grid technology also challenges the statuesque about what a woman can or cannot do as energy jobs are mostly considered man’s job. For example, in Kenya, women were trained as solar technicians and then were hired to repair the solar lanterns in the village. In a follow-up survey, men reported that seeing women install solar panels on the roof changed their perception about what a woman can do. The women, on the other hand, responded that this training made them more confident and empowered[21]. Thus, involving women in nontraditional jobs are important to uplift women’s status in society.

- ↑ UNDP. (2007a). Gender mainstreaming: A key driver of development in environment & energy.Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/environmentenergy/sustainable_energy/gender_mainstreamingakeydriverofdevelopmentinenvironmentenergy.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 _

- ↑ _

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedUNDP, 2007b - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHabtezion, 2012 - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLambrou & Piana, 2006 - ↑ World Bank, 2005

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKöhlin, Sills, Pattanayak, & Wilfong, 2011 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedUNEP, 2017 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMahat, 2011 - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIEA, 2017 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMikul et al., 2018 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKhandker, Barnes, Samad, & Minh, 2009 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEnergypedia, 2019 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIIaria, 2019 - ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKöhlin et al., 2011 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedStandal, 2010 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBarron & Torero, 2014 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDinkelman, 2011 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGlemarec, Bayat-Renoux, & Waissbein, 2016 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWinther, Ulsrud, & Saini, 2018