Inclusive Energy Distribution Strategies for Energy Access Programmes and Companies

Overview

Many companies face difficulties in reaching the “last mile” consumers, “the most vulnerable populations in isolated rural areas”[1]. Hence, many people do not have access to modern energy.

Therefore, many initiatives (public, donor funded, or private companies) have identified different and innovative distribution strategies. Inclusive means that they also include the “last mile” consumers at the bottom of the pyramid. (see inclusive business IFC)

This article outlines some of these distribution strategies, related challenges and further recommendations how to implement them. For technology-specific strategies, please refer to: pico PV distribution and cookstove dissemination strategies.

Inclusive Distribution Strategies

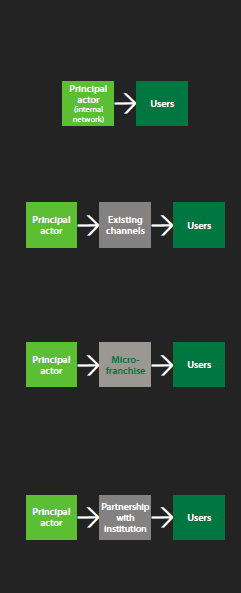

There are four models with different distribution strategies:[1] and [2]

- Internal network (the energy company carries out the distribution, proprietary distribution channel)

- Existing sales channels (distributor-dealer channel)

- Micro-franchises (including rental/leasing systems)

- Institutional partnerships

Figure: Distribution strategies for energy access.[1]

|

Internal network: in this strategy, the company that provides the service also sells it through a network of outlets with paid staff. + direct marketing to the consumers. + one of most effective ways of communicating with the clients. - an extensive sales force in each of the areas of influence is required (particularly expensive in remote rural areas). | |

|

Existing sales channels: with this strategy, the company supplying the service gets support from already existing sales and distribution outlets (general or specialized). This model is widespread. - turning a heterogeneous retailer’s network into an adequate distribution network might be complicated - ensuring adequate after sales service might be challenging. | |

|

Micro-franchises: This strategy constitutes an intermediate solution between the two examples above. - small local entrepreneurs get franchisee packs (including such aspects as initial training, marketing support, funding...) + for the initiative, it is cheaper to their own network of franchisees than their own workforce. - safeguarding the reputation of the brand. | |

|

Institutional partnerships: this strategy consists of forming a partnership with a relevant actor with access or connection to a great number of potential consumers (for example NGOs, suppliers of other products or even the government itself) to provide the product service directly to them. - Third party must be capable of doing business. + Third party might have already be popular/known to customers. |

Challenges for Inclusive Distribution Initiatives

Challenges for these initiatives targeting the last mile consumers, are the limited funding opportunities among donors and public finance, identifying the most suitable quality technological solutions and lobbing for a favourable political environment.

In the long run, sustainability of such initiatives is only granted by identifying the best business model that allows them to become independent from external subsidies. Furthermore, most initiatives work in areas with low population density and therefore, experiences from other areas should also be taken into account along with readapting the model to cultural and social differences of the target area. Similarly, the advantages and disadvantages of the different models should also be weighed for each specific case.[1]

In addition, many households do not pay for their energy needs in cash and have little disposable income to afford energy services. Furthermore, bringing energy services to those remote areas (often with very low population density) is more expensive than in their urban counterparts. In some areas, distribution costs account for 50% of the price.[3] Therefore, there is a need for innovative financing models.

Different innovative financing models are [2]

- One-Stop-Shop model, (sustainable energy products and finance are provided by the same organization)

- Financial institution partnering with energy enterprise,

- Umbrella partnership model (energy enterprise partners with an institution that manages a network of local financial institutions (e.g. a union or organization of credit cooperatives, etc.),

- Franchise/Dealership Model (that allows customers to payment in instalments),

- Brokering Model (A third-party organization or individual is paid by the finance provider and the energy enterprise to market energy products)

- Pay-as-you-go Model / Lease-to-own Model (customers pay regular on demand or on a monthly basis).

Case Studies of Distribution Models

The table below includes eight case studies from ADB report 2016, which demonstrates how innovative strategies can help to reach the last mile consumers by building on the lessons learnt in one country and then transferring and adopting them to the local context in another country. Similarly, suitable case studies from the IEA report ‘Innovative Business Models and Financing Mechanisms for PV Deployment in Emerging Regions’ are added to the table.

Their inclusive distribution aspects and financing aspects are highlighted. Furthermore, information on the respective technology, and relevant public policies are outlined.

Table: Overview of case studies with respective distribution model, finance, technology and public policy.[1] and [4]

|

Case |

Distribution model |

Inclusive distribution |

Finance |

Technology |

Public policy |

|

ACCIONA Microenergia Mexico[1] |

Own agents, institutional partnerships |

Maintenance as a way to create local employment |

Equipment50% subsidized |

Latest lithium-based batteries. Easy to install and maintain equipment |

Public-Private Partnership with regional Government |

|

Existing sales channels |

Support to entrepreneurs for marketing and maintenance of devices. Building on existing distribution networks |

Pay for performance mechanism to encourage micro-financing institutions. Pay through cell phone (pay as you go) in testing phase |

Systems testing and validation campaign prior to marketing. Locally adapted systems (cookstoves) |

Collaboration with public institutions for the development of quality standards to strengthen other aspects of the model | |

|

Energetica Bolivia [1] |

Micro-franchises |

Micro-franchises network for marketing and maintenance of devices |

Sale in instalments adapted to the user |

Close relationship with main supplier allowing adjusts in product design to better meet market needs |

Support from municipalities for awareness and strengthening of user trust |

|

Ilumexico Mexico [1] |

Internal network |

Own network of distribution centres for products and services. Building on existing distribution networks |

Sale on instalments adapted to user |

Simple systems, easy to use, adapted, installable by users. Set in modules to progressively extend use of devices |

Authorities provide information to identify off-grid users and access to communities |

|

Guascor/Eletrobras Amazonas Energia Brazil [1] |

Institutional partnerships |

Development of local retailers thanks to prepayment schemes. Collaboration with local NGO to facilitate dialogue with communities |

Public funding with cross subsidies |

Flexible network. Centralized electric and climate data for all systems |

Joint learning process between company and regional and central government. Public funding for universalizing access in remote areas |

|

Tecnosol Nicaragua [1] |

Internal network, existing sales channels |

Micro-distributors network. Creation of a non-for-profit institute linked to company |

Agreements with micro-financing entities and innovations in cooperation with international organizations |

Marketing of peripheral equipment adapted to core features for generating solutions (TV, radios, lamps...) |

VAT exemption for solar panels and batteries |

|

SunnyMoney Tanzania [1] |

Institutional partnerships, micro-franchises and existing sales channels |

Use of public schools for awareness raising and distribution purposes |

Uptake of losses in order to create market in the long term |

Use of quality standards approved by international initiatives. Transfer of information from clients to suppliers to improve products |

Tax exemptions for solar products. Pressure on government for development of enabling policies |

|

IDCOL Bangladesh [1] |

Institutional partnerships |

Defined partnership between all actors |

Efforts to facilitate clients paying for systems |

Emphasis on quality, warranty and maintenance services |

Progressive subsidies to benefit poorest and tax exemptions for solar products. Commitment from Government. Diversification of donors. Political independence of initiative |

|

Case/company |

Distribution model |

Inclusive distribution/ special features |

Finance |

Technology |

Public policy |

|

Azuri Techologies [4] |

Micro-franchises |

Hardware and service – in the form of top up codes – are sold to distribution partners in developing countries. Global, administrative database |

Pay-as-you-go (weekly installments), equity, working capital loans and loans from donors |

Lighting and phone charging systems |

. |

|

Grundfos (Denmark, in Kenya and Tanzania)[4] |

Institutional partnerships |

PPP approach with donor organisation; Grundfos installs, runs and repairs the systems for water service companies, NGOs, or community - based associations. Global, online water management platform |

Pay-as-you-use (Water-Card via M-Pesa) |

PV water pump technology |

. |

|

Chloride Exide Kenya[4] |

Own existing agents |

making best use of existing resources and infrastructure from the battery business, over 500 dealers and good reputation |

only direct sales, referals to MFI possible |

PV technology, SHS |

since 2013 revoked import duties and VAT on PV products |

|

Gham Power Nepal[4] |

Institutional partnerships |

the company provides complete solar project development, EPC and O&M services to businesses, rural communities and residences. Financing partner is CEDB. |

lease-to-own model; funds from international and national investors |

urban PV micro-grids in existing diesel grids |

. |

Further observations based on the case studies are:

- Along with facilitating access to energy, all initiatives also bring entrepreneurship and business opportunities to the remote areas.

- The structure of all initiatives observed had weaknesses (high operational costs, difficulty to identify the suitable business model, weak managing operations and networks, etc.)

- All initiatives foster the capacity to have a dialogue with the local population.

- The networks are linear and do not (yet) include the reverse logistic for waste management (for e.g. batteries).[1]

- Fine-tuning a business model can easily take time (months or years). The specific regulatory, economic, social and cultural situation in a region has to be well understood and addressed when generating new business models.

- Successful business models usually include a financing component. While traditional trading companies seem to have trouble with financing, younger firms seem to be able to manage this.[4]

Recommendations for Designing Inclusive Distribution Strategies

The following recommendations could be considered by similar initiatives or those initiatives while expanding to other regions:

- Build on existing distribution networks.

- Share the inclusive distribution energy network with others to supply other products and services such as food products, medicines etc.

- Diversify the range of products supplied by the distribution network.

- Incorporate new actors from the service sector into the partnerships.

- Implement advanced management and information systems.

- Build capacities among all the actors in the distribution chain.

- Develop reverse logistics for products.

- Share lessons learned among the different initiatives and actors.

- Build partnerships with financial institutions and capacities within the initiatives themselves.

- Broaden funding sources.

- Incorporate innovations in payment methods.

- Develop and/or harmonize technological standards and manuals and training materials.

- Promote technological collaboration.

- Test the incorporation of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT).

- Create coordination spaces between actors.

- Link initiatives to existing international Initiatives: e.g. “Sustainable Energy for All”, the“Alliance for Rural Electrification” or “Lighting Africa”.

- Reinforce the role of regional and municipal governments.

- Search for other types of collaborative instruments with the private sector. [1]

- Pay particular attention to the distribution channels and marketing activities to reach a large customer base.

- Use well designed hardware to allow easy installation by customers or local technicians.

- Use systems that are easy to operate and largely maintenance free.

- Identify appropriate financing mechanisms addressing the limited purchasing power.[4]

Further Information

- Lamp distribution models

- PicoPV Diffusion

- Solar Lantern Dissemination Models and Their Economic Viability#Conclusion

- Business Operation Models for Solar Home Systems (SHS)

- Solar Marketing

- Commercialisation of Cookstoves: Marketing Improved Cookstoves

- A Study on Biomass Cookstove Business Models from Asia and Africa

- ‘Implementation Strategies for Renewable Energy Services in Low-Income, Rural Areas. Keys to Achieving Universal Energy Access Series Brief 1’. Washington DC: World Resources Institute, 2013. http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/pdf/implementation_strategies_renewable_energy_services_low_income_rural_areas.pdf

- Lighting Africa. ‘Solar Lighting for the Base of the Pyramid - Overview of an Emerging Market -’, 2014. http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/a68a120048fd175eb8dcbc849537832d/SolarLightingBasePyramid.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Fernández, Xoan, and Carlos Mataix. ‘Sustainable Energy Distribution in Latin America. Study on Inclusive Distribution Networks.’ Innovation and Technology for Development Centre at the Technical University of Madrid (itdUPM), 2016. http://mifftp.iadb.org/website/publications/dd7fa2fb-592b-47ca-9fdf-20fea4763d4d.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Scott, Andrew, and Charlie Miller. ‘Accelerating Access to Electricity in Africa with off-Grid Solar - - Research Reports and Studies - 10230.pdf’. Overseas Development Institute, 2016. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10230.pdf.

- ↑ Lighting Africa. ‘Solar Lighting for the Base of the Pyramid - Overview of an Emerging Market -’, 2014. http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/a68a120048fd175eb8dcbc849537832d/SolarLightingBasePyramid.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Meier, Thomas. ‘Innovative Business Models and Financing Mechanisms for PV Deployment in Emerging Regions’. Report IEA - PVPS T9 - 14:2014, 2014. http://www.iea-pvps.org/index.php?id=311&eID=dam_frontend_push&docID=2350.