Promotion of Private Sector Participation

The term 'private' loosely describes all non-governmental parties; it has come into general use although its precise meaning is not always clear. The term is applied conventionally in contrast to governmental or quasi-governmental, in effect to the public sector. Perhaps it would be more correct to employ the term non-governmental which is in any case more appropriate in connection with small-scale power supply where a number of non-governmental bodies other than strictly private individuals or corporations can playa significant role. The key to sectoral definition is perhaps that the promoter - the driving force for initiating and implementing a project - should be independent of government although he may well be subject to some measure of government supervision and, in some cases, benefit from active government participation.

The general approach to participation of the private sector in public electricity supply can be grouped into three categories:

- an open market policy in which the whole electricity sector, or particular sections of it, are available to investment of private capital under minimal governmental direction or control and allow free range to market forces;

- a controlled policy with government or public utility - as an instrument of government determining where and to what extent a private initiative can be brought to bear, the private sector activity being closely supervised and exposed to market forces to only a limited extent. Naturally, there are various degrees of control, mitigated through enabling measures to make the venture sufficiently attractive for private enterprise;

- a promotional policy for encouraging non-governmental organizations to participate in local electrification where it is of special concern to them. Here again, the range of possibilities is wide and may extend from exclusive licensing of non profit-making bodies to cost and benefit sharing with private promoters on a fully commercial basis. Regulatory arrangements will be shaped accordingly.

There are basically five ways by which participation by the private sector can be brought about:

- by government - national or local - through advertisement or direct approach to known interest groups or potential developers;

- by technical assistance or aid agencies who, having identified a problem area, are looking for a developer whom they can propose to government;

- by interest groups or concerned organizations who wish to foster electrification in a given locality;

- by individuals or corporations who are attracted by the commercial prospects of an electrification proposal;

- by companies looking for markets for their equipment and services.

A combination of any of these initiatives is possible; both local and foreign sources can be employed.

The choice of potential non-governmental sources that can be tapped for expertise and finance is wide but becomes narrowed in the context of the local situation. Whoever carries out the pre-investment studies - utility, development agency or consultant - will have to examine what sources are appropriate for the particular case and draw up an activities and funding schedule as a basis for further progression of the project. This schedule sets out the sequence of actions that must be taken and identifies potential investors who could contribute to the funding requirements. Many small hydro schemes have failed to materialize in spite of a favourable and bankable feasibility report because the implementation schedule, or action plan, was not acted upon; the link between the investigator and the developer had not been established. A contributory factor was also in many cases that grants or aid funds were available for the pre-investment work but were not sufficient to bring the project to fruition. New sources had to be looked for and a procedure for doing so had not been set up.

The significance of support from the private sector in the context of small-scale electrification, primarily from hydropower, the preconditions to be met and the issues involved are discussed below.

Loan

Equity participation

If the private investor were to be offered equity participation through his purchase of share capital, he would become part-owner - in proportion to his shareholding - of whatever new facilities are created or existing facilities are transferred or sold. He will thus become directly involved, or at least interested, in the management and operation of these facilities and in the supply arrangements for the markets to be served. The profitability of his investment will depend on the financial performance of the enterprise in which the share capital has been invested. There is no guaranteed return. The incentive for contributing to what is essentially risk capital has to be based on a forward estimate of the future yield on the subscribed capital. On a strictly commercial basis, the yield has to be competitive with the opportunity cost prevailing in the particular country. Foreign investors may like to base their investment appraisal on the return that can be earned from industrial investment at home but they must be quite clear that this yardstick is by no means appropriate for investment in a developing economy. If they are concerned with the socio-economic betterment in backward areas, they may have less stringent expectations and may indeed wish to use equity participation as a vehicle for technical and economic assistance.

Where a single investor, or a group of investors, can acquire or control a predominant share in the capital structure (debt and equity) of a new undertaking and where, because of centralisation, there is little prospect of public-sector involvement, the private financier may have the opportunity to take charge of the whole scheme throughout its development and construction phases and run it for an agreed period of time. Indeed, the primary objective of private-sector financial participation may be the scope this offers to build up a local privately run utility service. Governments will tend to strike a balance between their reluctance to abrogate responsibility for a public service, even if only localized in a remote area, and the advantages they - and the local population - achieve through a soundly based and forward looking development effort, in effect through making electricity available to an area previously starved of it.

A privatised local electricity undertaking centred on a small power source need not necessarily be financed entirely from either public or private funds. Mixed loan/equity financing is now common, with financial inputs contributed by governments, financing agencies and non-governmental sources and also supported by aid in appropriate cases. Depending on national policy, aid funds intended for the electricity sector may not always be directed to it. Although aid is becoming increasingly project orientated, some governments insist on channelling these funds to the national exchequer and making them available to the promoter of a particular scheme by way of a government loan, usually with fixed loan life and interest charges.

Equity participation implies contributing risk capital to an enterprise, under the condition that revenue will be generated out of which the shareholder can be recompensed. The precise nature of the enterprise is not material for the funding process as such; it is of course material for the investor. In principle, a distinction need not be made between programme and project finance although the purposes of each must be sufficiently clear and transparent to satisfy the investor that a reasonable return can in fact be achieved. In the hydro case, for example, a small utility may attract programme finance for development which is not necessarily linked with a single hydro scheme. On the other hand, a single scheme attracting project finance may be developed into a vertically integrated local utility warranting programme finance for further expansion. With a mixed funding package the loan and equity components must be devoted to the same objective to ensure compatibility of the financial inputs.

Concessionary Finance

A new power scheme can be contracted for in three ways:

- Contracts are let separately for all major items of the installation, sections of the civil works and components of the electro-mechanical equipment. Procurement and contract management as well as project coordination remains in the hands of the developer. The advantage of this arrangement is that competitive bids can be invited for each major plant item and some cost savings achieved in this way. On the other hand, specifications have to be prepared for each of the items, the bids evaluated and the work of a number of contractors monitored and coordinated. This work can be onerous and its expense may well outweigh any savings resulting from the competitive bidding procedure.

- The scheme is contracted for in packages, say one for the civil works and another for the electro-mechanical plant and equipment. The number of specifications and invited bids is thus greatly reduced and project management and supervision simplified. Coordination within each package is left to the contractor and, although he will make a charge for this service, competitive bidding will tend to keep his prices in check.

- The whole scheme is contracted for in one part on a turnkey basis. Turnkey bids are still competitive but the selected contractor will now be responsible for a full project management and coordination service; the developer will have no more than a monitoring function.

If the financing arrangements allow the developer a free hand for contract allocation and if the developer has adequate resources for undertaking the project management and supervision, he can follow whatever contracting procedure is most suitable for his particular purpose. Under grant/loan financing, the borrower remains free to follow his own investment policy - subject to restrictions on sources in the case of nationally-tied loans - and the lender retains no interest in the facilities created under the loan other than requiring normal commercial collateral security and appropriate guarantees. It is immaterial in this connection whether any of the investment funds come from public or private sources.

Since much of the expertise and the plant and equipment employed under any of the three contracting arrangements will come from the private sector, it is to be expected that finance for development and construction should also be sought from that source. Competition between industrialised countries has encouraged banks and private sector financing institutions to make available loan capital for specific projects on concessionary terms with a long loan life and low interest rate; both are favourable in comparison with the terms offered by public sector financing institutions and with commercial terms. Loans are provided in two ways:

- in the form of buyers's credit, which leaves the borrower free to place contracts with whoever he wishes (subject to national restrictions in the case of tied loans).

- in the form of suppliers' credit under which services, materials and plant are offered on lease terms matched to the most favourable concessionary rates that can be secured. Contract arrangements are not limited by type of service or plant but they are of course restricted to the particular suppliers that offer the credit terms.

Both credit facilities often enjoy the support from government agencies of the exporting countries and can contain an element of grant or aid in kind (i.e aid given indirectly through credit support in the form of "seed money").

Training and technology transfer often did not prove adequate in the past to keep a new plant in satisfactory operating condition, particularly in the case of small schemes which suffered from marginalisation of effort due to the overriding needs of the central areas. Packages financed under suppliers' credit were thus expanded to include post-commissioning support. Cost-effective management usually meant that the supply was limited to a turnkey plant for which the supplier could offer a range of follow-on options. These are the following:

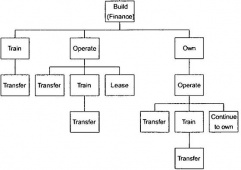

Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT)

Under Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) contracts the supplier provides and installs the plant and includes a subsequent operating service in his supply package. The plant usually remains the property of the borrower and he disposes of the electricity produced. He will take over the operation of the plant after a pre-arranged span of time. The aim is to cross the interface between construction and routine operation gradually and expertly and to give time to the ultimate owner to become fully familiar with all aspects of the plant's functioning.

Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT)

Under Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT) contracts the plant remains the property of the supplier and is operated by him for an agreed period of time. The electricity produced is sold on pre-arranged terms to the ultimate owner or to the local utility. This is a first step in privatisation. The duration of private ownership depends on the commitment the supplier is prepared to take on and the extent to which government or the national utility will accept a privately owned plant. Throughout the period of ownership, the supplier will be reimbursed through the revenue from electricity sales; if the period of ownership is too short to permit full cost recovery by the supplier, the ultimate owner may have to pay a balancing charge on transfer.

Build-Own-Operate-Train-Transfer (BOOTT)

Build-Own-Operate-Train-Transfer (BOOTT) contracts these are similar to BOOT, but include a training component prior to transfer for the plant to the ultimate owner. Training is intended to ensure that local operating personnel becomes fully familiar with the characteristics of the plant and is able to run it safely and effectively. International development agencies now consider inclusion of a training component to be an essential feature of a turnkey project.

Build-Own-Operate (BOO)

Build-Own-Operate (BOO) contracts, or DBFO (design, build, finance, operate) contracts, are a more advanced form of privatisation in which the plant remains in the hands of the original supplier for an indeterminate period of time, limited only by the duration of government consents on private-sector inputs to the public utilities system. This is an attractive option from the public point of view because an electricity service is made available at no cost to the public purse. The scheme can be financed by a consortium of private and public sources and the supplier can also form a team of different contracting and service organisations. The expertise of other utilities can likewise be drawn on.

Build-Operate-Lease (BOL)

The plant is built for and owned by the local utility, or by the ultimate owner as previously mentioned, and is leased back either to the original turnkey supplier or to an operator working in consort with this supplier. The critical point in a lease arrangement is that the costs incurred by the original supplier have to be covered with an adequate margin. This may be satisfactory if he can run the plant for a sufficiently long time and obtain sufficient revenue from electricity sales to recover the original investment and the ongoing operating and maintenance expenses. If, in addition, he has to pay a license fee to the ultimate owner and if, at the same time, power sale rates are too low to permit proper cost recovery, the concept will not be attractive for a private investor. It should be borne in mind that sale of electricity to a newly-developed market and a hitherto underprivileged population is unlikely to yield a satisfactory return in the early years. If the service had been provided by the National Utility, the return achieved could have been boosted by cross-subsidisation from consumers of greater purchasing power or from more profitable parts of the network.

Other combinations will no doubt be developed in time.

Suppliers' credit now forms the principal vehicle for private-sector inputs to electricity supply. The package includes final design of the scheme, construction works on site, manufacture and installation of plant and equipment, construction supervision, commissioning, operation, delivery of the output to the pre-determined parties and all financial inputs consistent with this scope of supply. The costs of other pre-investment investigations which may not be covered from the developer's own funds or from aid can also be included in the package, the supplier then becoming involved in the project from its initial identification or soon after. Interfaces between different parties can be avoided in this way and the preparatory work - especially for a small project - simplified and cheapened. Appropriate performance guarantees will still be asked for but will now involve a group of contractors and financiers; the negotiations are likely to be protracted. The linkage of financing conditions with the performance of the plant and with extended repayment periods can be of considerable help to the developer in cases where transfer is ultimately envisaged. Where the plant remains in the supplier's hands for an unspecified period, he will aim to redeem his investments out of the revenue he can obtain but he will have to face the difficulty of converting local revenue into the currency in which the imported part of the original investment was procured. Transfer of local revenues into foreign currency may be difficult; suitable conversion arrangements involving government intervention will have to be incorporated in the original contract.

Buy-Out and Lease

Non-governmental management and operation of a local utility is generally treated as a separate issue from the installation of a generating plant. It is licensed by governments:

- where their own resources are not sufficient for providing an effective service;

- where the non-governmental sector can offer such a service;

- where socio-economic needs are recognized to be pressing.

Provision of capital or plant does not by itself confer a prescriptive right for subsequent involvement in the running of the scheme and in the distribution and marketing of its output; this has to be negotiated for even where governments may wish to be relieved of this task. The following text refers to the transfer of an existing plant from the public to the private sector for the very purpose of relieving the owner from further responsibility for its operation. Existing means in this context that the plant has been satisfactorily commissioned and is now owned by a public entity.

Take-over and running of an existing hydro station will probably interest only those parties that either draw direct benefit from the output or, for charitable reasons, want to encourage better and more widespread local use of electricity. Such parties may be:

- commercial or industrial undertakings wishing to control or firm up their power supply;

- local interest groups or co-operatives wishing to be assured of a regular and secure supply;

- local, national and foreign welfare organizations or charities wishing to see an improved electricity service in the particular locality.

Take-over, or in effect privatization, of small local plants is rarely motivated by profit. The scope for profitability is likely to be severely limited by the low purchasing power of the consumers and consequently by the low tariff rates that have to be maintained.

There are basically two ways by which an existing plant is transferred to private management:

Buy-Out

A buy-out involves the straightforward purchase of the existing assets by lump-sum payment, deferred payment through annual installments or an injection of equity.

Deferred Payments

In this method, the existing owner gives in effect a loan to the purchaser. The loan is redeemed over an agreed period of time by annual charges of principal (a proportion of the value of the assets on take-over) and interest on the outstanding amount of the loan. Deferred payments can also be in the form of an annuity at fixed annual installments payable over the agreed redemption period.

Equity Participation

The purchaser takes equity capital up to the value of the plant at the time of take-over. The yield on the issued capital remunerates the vendor but a management company will now have to ensure that the equity is adequately serviced; profits arising out of operating revenue will have to be remitted to the equity holder.

Valuation

The value of the plant at the time of purchase has to be properly established. If it is an isolated scheme, agreement on a purchase price can be based on the depreciated value of the original investment in the plant, depreciation being computed up to the time the plant is sold. In addition, the vendor may require to be remunerated for the loss of profit he suffers by foregoing future sales of electricity; this matter arises only if indeed there has been a profit and if electricity has not been sold either at a loss or at a break-even price. The capitalized loss of profit would normally be the present-value of anticipated annual profits over an agreed span of time. A further consideration is the value of the resource that is being transferred. There are basically two possibilities:

- The water resource is owned by the public and exploited by the public sector; current ownership confers on the exploiter free use of the resource. On transfer to a new owner of the water-to-power conversion facilities - the site and the plant - the current owner can either:

(a) transfer the water rights for the capitalized benefit that can be derived from the water rights; this will in effect be the loss of profit as mentioned above.

(b) licence use of the water rights for a periodic fee and for a given period of time, with provision for periodic reconsideration of the licence conditions.

- Rights for resource exploitation are held by the body currently operating the scheme. Transfer conditions are then dependent on the terms under which the rights are held. The rights may be transferred as part of the inventory of the plant, or sold or leased as in the first case.

It is important to avoid double-counting the benefits of resource exploitation, i.e. both as water rights and as a source of profit. An unduly high water rate would reduce or eliminate all profit or, alternatively, raise electricity costs to unacceptable levels.

Determination of buy-out values follows basically the same approach as that used for privatisation of electricity supply facilities i.e. it requires asset valuation as described above. This can be a fairly complex matter but, in the case of a small plant, shortcuts can probably be introduced by agreement between vendor and buyer.

Lease

The plant remains the property of the original owner but is leased to a new operator. This means that the latter pays a licence fee or royalty to the owner. The fee is based on the capital charges or redemption payments to be defrayed on this plant, on the assumption that the plant is not yet fully depreciated at the time of purchase. A goodwill payment may also be required by the owner for loss of profit. The purchaser takes over the operation and collects the revenue. Naturally, a lease arrangement is only feasibility if the revenue likely to be obtained is sufficient to pay for the demands of the original owner and the running expenses of the plant.

A special form of lease is the contracting-out of operation and maintenance to a management company. In this case, the original owner retains the plant and also collects the revenue. He pays an agreed service fee to the management company. He can thus benefit from hiring outside expertise without affecting his position with respect to his power plant.

As in the case of turnkey contracts, buy-out and lease arrangements also offer scope for developing new approaches in due time.

Experience with Private Sector Participation:

PSP Hydro - Rwanda:

The PSP Hydro project in Rwanda supports the development of privately owned and operated Micro Hydro Power plants. So far two plants have been commissioned within the framework of the project, the first in mid 2010 and the second in April 2012. Further reading at EnDev Rwanda.