Promotion of Private Sector Participation

The term 'private' loosely describes all non-governmental parties; it has come into general use although its precise meaning is not always clear. The term is applied conventionally in contrast to governmental or quasi-governmental, in effect to the public sector. Perhaps it would be more correct to employ the term non-governmental which is in any case more appropriate in connection with small-scale power supply where a number of non-governmental bodies other than strictly private individuals or corporations can playa significant role. The key to sectoral definition is perhaps that the promoter - the driving force for initiating and implementing a project - should be independent of government although he may well be subject to some measure of government supervision and, in some cases, benefit from active government participation.

The general approach to participation of the private sector in public electricity supply can be grouped into three categories:

- an open market policy in which the whole electricity sector, or particular sections of it, are available to investment of private capital under minimal governmental direction or control and allow free range to market forces;

- a controlled policy with government or public utility - as an instrument of government determining where and to what extent a private initiative can be brought to bear, the private sector activity being closely supervised and exposed to market forces to only a limited extent. Naturally, there are various degrees of control, mitigated through enabling measures to make the venture sufficiently attractive for private enterprise;

- a promotional policy for encouraging non-governmental organizations to participate in local electrification where it is of special concern to them. Here again, the range of possibilities is wide and may extend from exclusive licensing of non profit-making bodies to cost and benefit sharing with private promoters on a fully commercial basis. Regulatory arrangements will be shaped accordingly.

There are basically five ways by which participation by the private sector can be brought about:

- by government - national or local - through advertisement or direct approach to known interest groups or potential developers;

- by technical assistance or aid agencies who, having identified a problem area, are looking for a developer whom they can propose to government;

- by interest groups or concerned organizations who wish to foster electrification in a given locality;

- by individuals or corporations who are attracted by the commercial prospects of an electrification proposal;

- by companies looking for markets for their equipment and services.

A combination of any of these initiatives is possible; both local and foreign sources can be employed.

The choice of potential non-governmental sources that can be tapped for expertise and finance is wide but becomes narrowed in the context of the local situation. Whoever carries out the pre-investment studies - utility, development agency or consultant - will have to examine what sources are appropriate for the particular case and draw up an activities and funding schedule as a basis for further progression of the project. This schedule sets out the sequence of actions that must be taken and identifies potential investors who could contribute to the funding requirements. Many small hydro schemes have failed to materialize in spite of a favourable and bankable feasibility report because the implementation schedule, or action plan, was not acted upon; the link between the investigator and the developer had not been established. A contributory factor was also in many cases that grants or aid funds were available for the pre-investment work but were not sufficient to bring the project to fruition. New sources had to be looked for and a procedure for doing so had not been set up.

The significance of support from the private sector in the context of small-scale electrification, primarily from hydropower, the preconditions to be met and the issues involved are discussed below.Three types of private sector inputs are presented:

- loan,

- equity participation,

- concessionary finance.

Loan

There is still considerable sensitivity in government circles to the opening-up of strategically and economically important public services - not only in the electricity sector - to non-governmental participation, even if carefully regulated and controlled. At the same time, there is also some nervousness in the private sector over entering into long-term commitments in a government dominated field, particularly in view of the risks to which the private party may be exposed.

Both parties may therefore aim initially at only an "arm's length" relationship with minimal mutual involvement and strictly limited risks. This can be achieved through subscription to loan capital - bonds or debentures - issued by governments or government controlled and quasi-governmental utilities. The private sector can thus contribute through arm's length financing to the capital needs for power system expansion without being in any way involved in the management and operation of any part of the utility service or being dependent on its financial success. Bonds and debentures, backed by the government or by governmental agencies, national or international, offer a fixed and guaranteed yield and have a firm redemption life (often termed loan life). The lender is thus shielded from a variable and, to some extent, unpredictable performance of the utility. The governmental utility service is free to develop and run its system as it considers appropriate. Marginal electricity supply development can be financially supported in this way provided the utility has the capacity to take on the necessary development effort and cope with subsequent exploitation. One of the causes of marginalisation is, however, that this capacity has been fully absorbed by the effort devoted to the central areas and that no significant spare capacity can be mobilized for local electrification.

Participation of private capital by way of loans may be more attractive in cases where a small scheme is promoted from the outset as a non-governmental venture by particular interest groups or NGOs. The developer or promoter may then actively canvass for private support and attempt to manage the risk of failing to meet loan redemption commitments. The private investor will remain shielded from the commercial performance of the enterprise and yet have the satisfaction of contributing to a socially and economically important activity, if only in a strictly local context. This role may be particularly attractive for charitable bodies.

Private sector contributions to loan financing can also be secured indirectly through the provision of funds to aid and financing agencies which in turn support or invest in electrification projects. There are many possibilities, from donations to charitable or non profit-making bodies to the purchase of loan stock or bonds issued by multi-lateral agencies - the World Bank and Regional Investment Banks, for example. The funds solicited by multi-lateral agencies are not normally earmarked for a specific purpose but regular statements on the disposition of such funds are published; a fixed return is guaranteed by the governments supporting the agencies in question.

A clear distinction has to be made between:

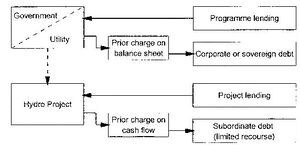

- lending to government or utility. The disbursement of funds for a specific project remains the responsibility of one of these bodies. The lender stays at "arm's length" although he may wish to scrutinize the development programme for which finance is sought; this is certainly done by the financing agencies. Programme loans (which are not tied to a specific project) form a corporate or sovereign debt and a prior charge on the balance sheet of the undertaking concerned; the loan charges incurred by the undertaking have to be met before any other of its borrowings are paid off. Debt management can be difficult where there is scarcity of development capital and defaulting on sovereign debt is not uncommon. Programme lending can therefore be risky in spite of its priority status.

- lending for a particular project (sometimes termed "direct lending"). The organization responsible for project implementation - which may well be government or utility - has to form a separate and financially independent entity to manage this project. With such Project Loans, loan sums are redeemed from the cash flow generated by the project. The borrower's debt is subordinate to indebtedness incurred directly by government or utility. The lender has recourse only to the assets created out of his loan; hence he is lending with "limited recourse". The value of the assets created is his security or collateral but he will naturally look for more far-reaching guarantees from governments - his own and the borrower's and from national and international agencies.

The two alternative loan arrangements are presented in the diagram. Programme lending at government or utility level is still widely practised by public and private financing institutions, especially also in connection with the structural adjustment of economic resources. The focus is however moving more towards project lending and hence towards closer involvement of the lender in the disbursement of the funds and in the objectives of the development proposal. Private-sector inputs, particularly for small schemes, tend now to concentrate on the funding of specific projects, even in the face of opposition to the proposed development on social or environmental grounds.

Equity participation

If the private investor were to be offered equity participation through his purchase of share capital, he would become part-owner - in proportion to his shareholding - of whatever new facilities are created or existing facilities are transferred or sold. He will thus become directly involved, or at least interested, in the management and operation of these facilities and in the supply arrangements for the markets to be served. The profitability of his investment will depend on the financial performance of the enterprise in which the share capital has been invested. There is no guaranteed return. The incentive for contributing to what is essentially risk capital has to be based on a forward estimate of the future yield on the subscribed capital. On a strictly commercial basis, the yield has to be competitive with the opportunity cost prevailing in the particular country. Foreign investors may like to base their investment appraisal on the return that can be earned from industrial investment at home but they must be quite clear that this yardstick is by no means appropriate for investment in a developing economy. If they are concerned with the socio-economic betterment in backward areas, they may have less stringent expectations and may indeed wish to use equity participation as a vehicle for technical and economic assistance.

Where a single investor, or a group of investors, can acquire or control a predominant share in the capital structure (debt and equity) of a new undertaking and where, because of centralisation, there is little prospect of public-sector involvement, the private financier may have the opportunity to take charge of the whole scheme throughout its development and construction phases and run it for an agreed period of time. Indeed, the primary objective of private-sector financial participation may be the scope this offers to build up a local privately run utility service. Governments will tend to strike a balance between their reluctance to abrogate responsibility for a public service, even if only localized in a remote area, and the advantages they - and the local population - achieve through a soundly based and forward looking development effort, in effect through making electricity available to an area previously starved of it.

A privatised local electricity undertaking centred on a small power source need not necessarily be financed entirely from either public or private funds. Mixed loan/equity financing is now common, with financial inputs contributed by governments, financing agencies and non-governmental sources and also supported by aid in appropriate cases. Depending on national policy, aid funds intended for the electricity sector may not always be directed to it. Although aid is becoming increasingly project orientated, some governments insist on channelling these funds to the national exchequer and making them available to the promoter of a particular scheme by way of a government loan, usually with fixed loan life and interest charges.

Equity participation implies contributing risk capital to an enterprise, under the condition that revenue will be generated out of which the shareholder can be recompensed. The precise nature of the enterprise is not material for the funding process as such; it is of course material for the investor. In principle, a distinction need not be made between programme and project finance although the purposes of each must be sufficiently clear and transparent to satisfy the investor that a reasonable return can in fact be achieved. In the hydro case, for example, a small utility may attract programme finance for development which is not necessarily linked with a single hydro scheme. On the other hand, a single scheme attracting project finance may be developed into a vertically integrated local utility warranting programme finance for further expansion. With a mixed funding package the loan and equity components must be devoted to the same objective to ensure compatibility of the financial inputs.

Concessionary Finance

A new power scheme can be contracted for in three ways:

- Contracts are let separately for all major items of the installation, sections of the civil works and components of the electro-mechanical equipment. Procurement and contract management as well as project coordination remains in the hands of the developer. The advantage of this arrangement is that competitive bids can be invited for each major plant item and some cost savings achieved in this way. On the other hand, specifications have to be prepared for each of the items, the bids evaluated and the work of a number of contractors monitored and coordinated. This work can be onerous and its expense may well outweigh any savings resulting from the competitive bidding procedure.

- The scheme is contracted for in packages, say one for the civil works and another for the electro-mechanical plant and equipment. The number of specifications and invited bids is thus greatly reduced and project management and supervision simplified. Coordination within each package is left to the contractor and, although he will make a charge for this service, competitive bidding will tend to keep his prices in check.

- The whole scheme is contracted for in one part on a turnkey basis. Turnkey bids are still competitive but the selected contractor will now be responsible for a full project management and coordination service; the developer will have no more than a monitoring function.

If the financing arrangements allow the developer a free hand for contract allocation and if the developer has adequate resources for undertaking the project management and supervision, he can follow whatever contracting procedure is most suitable for his particular purpose. Under grant/loan financing, the borrower remains free to follow his own investment policy - subject to restrictions on sources in the case of nationally-tied loans - and the lender retains no interest in the facilities created under the loan other than requiring normal commercial collateral security and appropriate guarantees. It is immaterial in this connection whether any of the investment funds come from public or private sources.

Since much of the expertise and the plant and equipment employed under any of the three contracting arrangements will come from the private sector, it is to be expected that finance for development and construction should also be sought from that source. Competition between industrialised countries has encouraged banks and private sector financing institutions to make available loan capital for specific projects on concessionary terms with a long loan life and low interest rate; both are favourable in comparison with the terms offered by public sector financing institutions and with commercial terms. Loans are provided in two ways:

- in the form of buyers's credit, which leaves the borrower free to place contracts with whoever he wishes (subject to national restrictions in the case of tied loans).

- in the form of suppliers' credit under which services, materials and plant are offered on lease terms matched to the most favourable concessionary rates that can be secured. Contract arrangements are not limited by type of service or plant but they are of course restricted to the particular suppliers that offer the credit terms.

Both credit facilities often enjoy the support from government agencies of the exporting countries and can contain an element of grant or aid in kind (i.e aid given indirectly through credit support in the form of "seed money").

Training and technology transfer often did not prove adequate in the past to keep a new plant in satisfactory operating condition, particularly in the case of small schemes which suffered from marginalisation of effort due to the overriding needs of the central areas. Packages financed under suppliers' credit were thus expanded to include post-commissioning support. Cost-effective management usually meant that the supply was limited to a turnkey plant for which the supplier could offer a range of follow-on options. These are the following:

Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT)

Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) contracts where the supplier provides and installs the plant and includes a subsequent operating service in his supply package. The plant usually remains the property of the borrower and he disposes of the electricity produced. He will take over the operation of the plant after a pre-arranged span of time. The aim is to cross the interface between construction and routine operation gradually and expertly and to give time to the ultimate owner to become fully familiar with all aspects of the plant's functioning.

Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT)

Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT) contracts where the plant remains the property of the supplier and is operated by him for an agreed period of time. The electricity produced is sold on pre-arranged terms to the ultimate owner or to the local utility. This is a first step in privatisation. The duration of private ownership depends on the commitment the supplier is prepared to take on and the extent to which government or the national utility will accept a privately owned plant. Throughout the period of ownership, the supplier will be reimbursed through the revenue from electricity sales; if the period of ownership is too short to permit full cost recovery by the supplier, the ultimate owner may have to pay a balancing charge on transfer.