Difference between revisions of "Senegal Energy Situation"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

Demand for charcoal derived from Senegalese forests is also likely to increase since there will be a phase-out of subsidies for butane gas in reaction to pressure from the West African Monetary Union, most likely prompting poorer households to return to their traditional fuel usage patterns. These traditional ways of cooking are generally characterised by very poor efficiency. | Demand for charcoal derived from Senegalese forests is also likely to increase since there will be a phase-out of subsidies for butane gas in reaction to pressure from the West African Monetary Union, most likely prompting poorer households to return to their traditional fuel usage patterns. These traditional ways of cooking are generally characterised by very poor efficiency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the 1970’s the government launched the national butanisation programme in order to re-place charcoal consumption by Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) through subsidies and pro-motion campaigns. In 2002, around 71 percent of urban households in Senegal and even 88 percent of households in Dakar used LPG as primary cooking fuel (ANSD 2006). The Se-negal Ministry of Energy estimated the annual saving of firewood and charcoal to be 70,000 tons and 90,000 tons, respectively.<br>Nevertheless, biomass resources and wood in particular continue to be unsustainably ex-ploited. In the urban and peri-urban Dakar region, the high demand for traditional fuels can only be met using wood sources 500 km away from the capital. While Senegal still counts a relatively high share of primary forests, deforestation leads to annual losses of forests of 0.5 percent, which comes close to the average of Western African countries. However, figures from FAO on Africa and Senegal in particular indicate that agricultural land clearance has been and will be the predominant cause of deforestation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Due to the high demand, the price of charcoal increased by 42 percent between 2005 and 2008, which is, however, still less than the increase in the ceiling price for LPG that increased by 48 and 63 percent for the two main bottle sizes (3.5 and 6 kg) respectively. Thereby, cooking energy prices soared disproportionately in light of consumer prices that only increased by 14 percent within the same time period. | ||

Some key figures: | Some key figures: | ||

| Line 31: | Line 35: | ||

*40,000 ha of forest are lost every year (to chopping for firewood, forest fires, desertification) | *40,000 ha of forest are lost every year (to chopping for firewood, forest fires, desertification) | ||

*the price of traditional fuels (firewood, charcoal) has more than doubled in the last 10 years | *the price of traditional fuels (firewood, charcoal) has more than doubled in the last 10 years | ||

| − | * | + | *between 5,400 and 6300 people annually die from diseases caused by indoor air pollution |

*45 % of Senegal’s primary energy demand are covered by firewood (31 % directly as firewood and 14 % as charcoal) | *45 % of Senegal’s primary energy demand are covered by firewood (31 % directly as firewood and 14 % as charcoal) | ||

Revision as of 14:55, 24 February 2011

Situation Analysis and Framework Conditions

Energy Situation

The Senegalese energy sector is relatively small. The total final energy consumption in 2006 was about 2.3 Million TOE or 0.2 TOE per habitant, half of the all-africa average (0.45 TOE).

Senegal’s energy balance is predominately biomass (58 %) and petroleum products (38 %). The lack of diversification is compounded by the absence of efficient technologies, a low density of distribution grid, as well as a lack of regulatory framework and weak financial structures.

Electricity and coal account only for 7 % and 4 % respectively. The figure of biomass is of particular interest as biomass is only used for cooking, mostly in rural areas. This fact is represented by the high energy consumption of the household sector, which is responsible for 54 % of the total energy consumption. Within this sector firewood (58 %) and charcoal (26 %) are by far the most important sources of energy, followed by LPG (11 %), Electricity (4%) and lampoil (1 %).

Senegal’s hydroelectric potential remains untapped. However with rainfalls predicted to decline by 17 % over the next 20-50 years, attention will have to be paid to hydro’s role in Senegal’s energy mix. The development of flow regime optimisation plans will help in this regard.

Energy Demand and Supply in the Household Sector

The following figure shows the development of the energy consumption in the sectors household, transport and industry.

Biomass

The described consumption pattern leads to a high pressure on Senegalese forests, especially as it´s unclear if the government will keep the high subsidies for LPG. And a big part of urban households still cooks with wood and charcoal. The use of biomass is one of the key factors responsible for the depletion of the country's forest stocks. In the medium term deforestation will create bottle-necks in the supply of cooking energy, particularly for the poorest households.

Demand for charcoal derived from Senegalese forests is also likely to increase since there will be a phase-out of subsidies for butane gas in reaction to pressure from the West African Monetary Union, most likely prompting poorer households to return to their traditional fuel usage patterns. These traditional ways of cooking are generally characterised by very poor efficiency.

In the 1970’s the government launched the national butanisation programme in order to re-place charcoal consumption by Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) through subsidies and pro-motion campaigns. In 2002, around 71 percent of urban households in Senegal and even 88 percent of households in Dakar used LPG as primary cooking fuel (ANSD 2006). The Se-negal Ministry of Energy estimated the annual saving of firewood and charcoal to be 70,000 tons and 90,000 tons, respectively.

Nevertheless, biomass resources and wood in particular continue to be unsustainably ex-ploited. In the urban and peri-urban Dakar region, the high demand for traditional fuels can only be met using wood sources 500 km away from the capital. While Senegal still counts a relatively high share of primary forests, deforestation leads to annual losses of forests of 0.5 percent, which comes close to the average of Western African countries. However, figures from FAO on Africa and Senegal in particular indicate that agricultural land clearance has been and will be the predominant cause of deforestation.

Due to the high demand, the price of charcoal increased by 42 percent between 2005 and 2008, which is, however, still less than the increase in the ceiling price for LPG that increased by 48 and 63 percent for the two main bottle sizes (3.5 and 6 kg) respectively. Thereby, cooking energy prices soared disproportionately in light of consumer prices that only increased by 14 percent within the same time period.

Some key figures:

- 40,000 ha of forest are lost every year (to chopping for firewood, forest fires, desertification)

- the price of traditional fuels (firewood, charcoal) has more than doubled in the last 10 years

- between 5,400 and 6300 people annually die from diseases caused by indoor air pollution

- 45 % of Senegal’s primary energy demand are covered by firewood (31 % directly as firewood and 14 % as charcoal)

The Senegalese government has recently published several policy orientations, thus beginning to address these extremely urgent issues. Nevertheless the Senegalese forest sector lacks institutional capacities and efficiency in order to launch basic reform processes and to implement sustainable changes on a large scale and to face deforestation.

Electricity

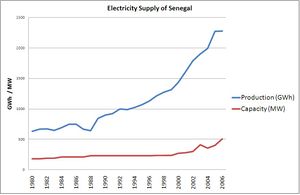

Since the year 2000 the electricity production is increasing annually by 7.2 % and was about 2,401 GWh in 2008,(see figure below), of which 82% of the total electricity generation is produced by petro power plants, 10% by hydropower plants, 2% by gas power plants, 2% by co-generation and 1% by renewable combustible and waste (e.g. biomass)[1]. Thereof 3.6 GWh are produced decentralized with PV application. In 2006 the households consumed 1,438 GWh or 144 kWh per person. But as the demand for electricity grows faster than the supply Senegal has to deal with serious problems. The state-owned electricity supplier SENELEC lacks an efficient organisational structure and investments in the power plants and in transmission lines in order to cope with increasing demand of 8 % annually. In addition, the reserve capacity decreased from 30 % to 11 % what causes scheduled or unscheduled outage of whole districts. Transmission losses, old thermal power plants and increasing oil prices result in high average power production costs of 60 FCFA/kWh.

Anyhow, the electrification rate is relatively high: in urban areas it reaches 75 % and nationwide it´s around 45 %.

Access to Electricity (% of households) 2000: 30% (58% urb.); 2006: 44% (77% urb.)

On the other hand, in 2008 only about 17 % of rural households have access to electricity. Recently, the government set the target to increase rural electrification to 50 % by 2012. The goal seems very ambitious and explains the high ranking of rural electrification on the political agenda.

Electricity Generation, Transmission and Distribution

Electricty Generation:

Senegal’s total installed capacity is 634.9 MW, but in 2008 only 548.8 MW were used. Of these 512.1 MW are connected to the national grid. SENELEC owns power stations with nearly 60 % of the total production capacity while 218.3 MW are private US-owned by GTI-Dakar and ESKOM-Manantali.

The major part is 'generated' by diesel plants, but there are also gas-, steam- and gas-steam power plants. Senegal uses 60 MW of the 200 MW Manantali hydroelectric power plant at the border with Mali. As a result the electricity price strongly depends on the world market oil-price and the local Diesel price in both - national grid as well as in mini-grids. Anyway, due to subsidies the price is relatively low.

Transmission:

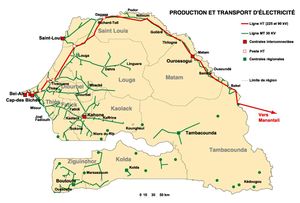

There are two grid-systems: the national grid at 90 kV (327.5 km) and the supranational grid at 225 kV (945 km). Both are operated by SENELEC. The grid only supplies urban areas around Dakar, Thies, St. Louis and Kaolack/Fatick with electricity. But there are several isolated networks in order to power some remote areas.

Length of Domestic Transmission and Distribution Lines 13477 km.

Number and Length of Power Cuts:

- From 2005 – 2008 the quality of service characterised by an increasing number of incidents and non-distributed energy.

- Severe rationing due to lack of production and several major cable faults led to a rise in cuts from 587 to 1792 Over the same 3 year period interruptions due to technical incidents on the 30 KV grid almost doubled from 1257 to 2219 on the 30 kV grid

- The number of high-voltage grid interruptions due to technical failures fell 16% from 150 to 126

The following map shows the current electricity transport lines as well as main power plants.

Distribution:

All distribution activities are carried out by SENELEC.

Rural Electrification

Senegal consist mostly of villages classified as small rural localities with less than 500 inhabitants (84 %). Such villages accounted for 46 % of the rural population in 2003. These communities are of less interest for private investors due to high investment costs and relatively low revenues.

The Senegalese government developed a concessionaire-model to electrify rural areas. The Senegalese Agency for Rural Electrification (ASER) is responsible for its implementation (see Public Institutions and Actors). The model works as follows:

It was decided to divide the whole of Senegal into concession zones (12 concessions remain after a consolidation). International donors and the Senegalese government provide large amounts of money to supply the concessionaires with sufficient funds for their rural electrification activities. The donors involved are the World Bank, the German development bank KfW (1 concession) and the African Development Fund. The government provides up to 70 % of funds required for investment and engineering. The concessionaire is charged with 20 % and the users with 10 %. End users will be charged with cost covering tariffs. All donors have dedicated a share of their funds (ca. 15 %) for the installation of renewable energy systems.

The first concession was awarded in 2008. Within the concessions municipalities can apply for ERIL loans (Electrification Rurale d’Initiative Locale – rural electrification through local initiatives) to implement electrification projects themselves. In ERILs, the same rules apply for subsidies as in the concessions (70 %/ 20 %/ 10 %). For all ERILs an application has to be prepared and submitted. Then, ASER and the respective concessionaire have to approve the project.

The concessionaires will start their rural electrification activities soon, but they will only reach a small part of the rural population. Following ASER's current strategy, almost all villages that are not located in vicinity of medium tension power supply lines will not be supplied with electricity within the next 10 to 15 years. In the concession zones of KfW in the Peanut Basin and the Casamance, for example, about 1 million people in 2,600 villages will not be connected to the grid.

Although in principle the two concession models of ASER (large-scale concessions (PPER), and concessions based on local initiative (ERIL)), in conjunction with the tariffs set by the regulatory authority, ensure profitability for the operators and thus continued maintenance (and hence sustainability), this was not yet proven in practice due to the small number of projects implemented and various delays in the administrative procedures.

Barriers to rural electrification are, among others, low purchasing power of the consumers (implying a need for subsidies if a broad range of people is to be targeted), the small number of qualified enterprises intervening on the rural market, and the incongruity of rural electrification funds and demand. In addition, administrative processes in the rural electrification agency ASER are lengthy and intransparent to potential operators (necessity for capacity building of ASER staff).

Institutional Set Up and Actors in the Energy Sector

Public Institutions and Actors

In 1997 Senegal began a reorganisation of its electricity sector following recommendations by the World Bank. It was decided to privatise the public utility SENELEC, to found the "Agence Sénégalaise d’Electrification Rurale" (ASER – Senegalese Agency for Rural Electrification) and to put in place the "Commission de Régulation du Secteur de l’Electricité" (CRSE – Regulatory Commission for the Electricity Sector).

The Ministry of Energy (Ministère de l’Energie) as the lead agency is in charge of formulating, coordinating, and setting overall objectives, policies, strategies, and general directives for the entire energy sector. Furthermore it is authorized to issue directives to SENELEC. The CRSE is responsible for the distribution and monitoring of concession and licences (except those for rural areas), for the market control (control of competition) and it fixes the end-user prices for electricity. ASER was founded in 2000 and is the governmental agency which is charged with the task of rural electrification. It is financed by the Senegalese government and international donores (such as Worldbank, GTZ, KfW, AfDB, IsDB). ASER tends the concessions for rural areas for private investors and finances 70% of the projects (see Rural Electrification section). Urban electricity supply remained within the responsibility of SENELEC/CRSE.

Non Governmental Service Providers for Rural Areas in the Field of Energy

Commercial Service Providers

During the 1990s, Senegalese companies sold about 2,000 PV systems per year, but the reorganisation of the electricity sector had a negative impact of the nascent Senegalese market for solar energy systems. Only 7 out of 18 solar companies survived the reform. However, 6 new companies have entered the market since 1998, raising the number of solar energy providers to 13. The companies are: SolarSenegal, ....The companies are mainly involved in installation and service for donor-funded systems while the market for unsubsidised systems is very small.

Micro Finance Institutions

- Government

The ministry in charge of micro-finance ist the "Ministére de la Famille,de la Solidarité Nationale, de la Sécurité Alimentaire, de l'Entreprenariat Féminin, de la Micro Finance et de la Petite Enfance".

- Senegal Ecovillage Microfinance Fund

The SEM Fund, or the Senegal Ecovillage Microfinance Fund, is a nonprofit organisation dedicated to poverty alleviation by providing affordable business loans aimed at strengthening the business skills and livelihoods of highly motivated microentrepreneurs that lack access to the commercial banking system.

Policy Framework

Renewable Energy Law

A renewable energy law was signed by president Abdoulaye Wade on Dec, 20 2010 and is currently effective. The law is kept rather general. All details will be determined in by-laws which are currently being elaborated. The text of the law can be found here.

Poverty Reduction Strategy and Energy Policy

Senegegal´s Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) pushes the poverty reduction agenda forward so as to meet the objective of raising economic growth to about 7 percent per year necessary to halve poverty by 2015, in line with the targets set out in the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

The PRSP names are ten overall objectives for the development of the energy sector:

- develop the institutional framework and production capacity for energy

- promote the engine of productive activities

- involve private operators, village associations and local authorities in the development of energy infrastructures and services;

- ensure the financing of activities aimed at developing the energy sector

- diversify energy sources and technologies

- promote the control of energy and renewable energy sources

- create an investment programme for access to energy services aimed at economic and human development

- provide better and safer public access to domestic fuels

- enhance access to energy services in rural and suburban areas so as to facilitate the working of basic infrastructures (schools, healthcare facilities, conservation infrastructures, etc.)

- improve access to oil and gas.

Land ownership and participation

1994: 33.4% 2002: 32.7% Agricultural population

National Energy Sector Development Strategy

The Lettre de Politique de Développement du Secteur de l’énergie (LPDSE) was approved in 2008 to cope with the fundamental problems of the energy sector. There are six main objetives:

- Development and usage of domestic energy resources, particularly biofuels and renewable energies.

- Diversification of energy sources for power generation: increase use of coal, biofuels, biomass (especially biomass produced in sustainable, participative forest management systems)

- Increase share of hydropower through the participation in regional cooperation projects such as OMVG, OMVS and WAPP

- Security in supply of oil products by building own refineries and close cooperation with oil producing countries.

- Increasing the electricity supply in rural areas especially pro social and productive uses

- Reducing the energy demand and increasing the energy efficiency

National Household Fuels Subsector Development Strategy

The Lettre de Politique de développement du sous-secteur des combustibles domestiques (LPDSCD) was also approved in 2008 and aims at

- the management of the supply side through participative forest management systems

- the management of the demand side through the dissemination of improved stoves, gas-stoves and alternative energy sources such as kerosene, biomass-briquettes and gelfuel among others.

- the improvement of the institutional and fiscal framework

- the dissemination of modern energy sources in rural areas (particularly for rural electrification issues).

Climate Change

Senegal already has some key adaptation elements in place. The country has a national contingency plan that includes studies of natural disasters such as flooding, and of the areas where disasters might occur. Maps showing projected cloud cover and wind speeds are available. Biomass consumption is also being tackled with substantial research on biomass issues and promotion of improved woodstoves.

Flooding of thermal plants is a real vulnerability that will need to be addressed. Already one plant has suffered severe damage from heavy rains.

Key Problems Hampering Access to Modern Energy Services in Rural Areas

Obstacles for Grid Based Rural Electrification

- Even though the concessionaires will soon start their rural electrification activities, they will only reach a small part of the rural population. Following ASER's current strategy, almost all villages that are not located in vicinity of medium tension power supply lines will not be supplied with electricity within the next 10 to 15 years. In the concession zones of KfW (German implementing agency for financial cooperation) in the Peanut Basin and the Casamance, for example, about 1 million people in 2,600 villages will not be connected to the grid.

- administrative processes in the rural electrification agency ASER are lengthy and intransparent to potential operators (necessity for capacity building of ASER staff).

- Although in principle the two concession models of ASER (large-scale concessions (PPER) and concessions based on local initiative (ERIL)), in conjunction with the tariffs set by the regulatory authority, ensure profitability for operators and thus continued maintenance (and hence sustainability), this was not yet proven in practice due to the small number of projects implemented and various delays in the administrative procedures.

Obstacles for Off Grid Energy Technologies and Services

- low purchasing power of the consumers (implying a need for subsidies if a broad range of people is to be targeted)

- small number of qualified enterprises intervening on the rural market

- incongruity of rural electrification funds and demand

References

- ↑ IEA-OCDE.2010.Energy balances of Non-OECD countries.Paris, France.p 249-250.

EnDev Senegal