Difference between revisions of "Secure Financial Feasibility"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) m |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

With only about 55% of the population having access to electricity<ref>IEA ''et al.'' (2020) ''Tracking SDG 7: Nigeria''. Available at: <nowiki>https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/country/nigeria</nowiki> (Accessed: 23 September 2022).</ref>, Nigeria is an attractive market for off-grid solar companies. This section will outline the challenges standalone solar (SAS) and mini grid developers face while accessing finance for their businesses, and provide some guidance on what can be done to tackle these. | With only about 55% of the population having access to electricity<ref>IEA ''et al.'' (2020) ''Tracking SDG 7: Nigeria''. Available at: <nowiki>https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/country/nigeria</nowiki> (Accessed: 23 September 2022).</ref>, Nigeria is an attractive market for off-grid solar companies. This section will outline the challenges standalone solar (SAS) and mini grid developers face while accessing finance for their businesses, and provide some guidance on what can be done to tackle these. | ||

| − | This section will firstly describe different key components of financing. Afterwards three challenges of accessing finance are highlighted, followed by three different guiding principles, each of them illustrated by practical examples from established companies. Please keep in mind that this section focuses on business financing and how to access finance for your company. Accessing finance is only one part of a successful business model. For more details on this area, please also consult the | + | This section will firstly describe different key components of financing. Afterwards, three challenges of accessing finance are highlighted, followed by three different guiding principles, each of them illustrated by practical examples from established companies. Please keep in mind that this section focuses on business financing and how to access finance for your company. Accessing finance is only one part of a successful business model. For more details on this area, please also consult the [[Design Business Model|Design Business Model]] section. |

| + | |||

| + | The following video gives an overview of different financing opportunities by the Nigerian Electrification Program for the clean energy sector: | ||

| + | {{#widget:YouTube|id=QAfRvqU0ze8|height=360|width=480}} | ||

==Definitions== | ==Definitions== | ||

| − | There are three funding sources that should be considered when searching for financing options in the off-grid sector. This chapter will give an overview of the most common options. Which options are most suitable for which company stage, will be discussed in detail later in the chapter | + | There are three funding sources that should be considered when searching for financing options in the off-grid sector. This chapter will give an overview of the most common options. Which options are most suitable for which company stage, will be discussed in detail later in the chapter “Target financing that is suitable for the maturity of your company”. |

| − | ''' | + | '''<u>Grant</u>''' |

A grant is a non-repayable award, mostly offered by governments or donors. Companies usually have to face a selection process in a competition with other applicants. | A grant is a non-repayable award, mostly offered by governments or donors. Companies usually have to face a selection process in a competition with other applicants. | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''<u>Equity</u>''' |

Investors are buying shares of the company in order to make money through dividends or by selling their stakes. | Investors are buying shares of the company in order to make money through dividends or by selling their stakes. | ||

| − | |||

| − | ''' | + | '''<u>Debt</u>''' |

Unlike grants, debts are borrowed funds which have to be repaid plus the amount of interest. Debt finance is the main used instrument in the SAS and mini grid sector. | Unlike grants, debts are borrowed funds which have to be repaid plus the amount of interest. Debt finance is the main used instrument in the SAS and mini grid sector. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| − | |+Table 3: Financing models for the OGS sector <ref>USAID and Power Africa (2022) PA NPSP Off-Grid Market Intelligence Report. Available at: <nowiki>https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00ZB5X.pdf</nowiki>.</ref> | + | |+Table 3: Financing models for the OGS sector <ref>USAID and Power Africa (2022) PA NPSP Off-Grid Market Intelligence Report. Available at: <nowiki>https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00ZB5X.pdf</nowiki>.</ref> |

!Type | !Type | ||

!Description | !Description | ||

| Line 37: | Line 39: | ||

==Challenges in raising finance== | ==Challenges in raising finance== | ||

| − | The off-grid electrification sector is growing and attracting more investments and financing. However, there are still difficulties in accessing funding, especially for smaller companies which have been unable to raise equity. Therefore, most of the funding flows to large | + | The off-grid electrification sector is growing and attracting more investments and financing. However, there are still difficulties in accessing funding, especially for smaller companies which have been unable to raise equity. Therefore, most of the funding flows to already established, large companies. This section focuses on the main challenges off-grid solar (OGS) enterprises face when raising finance. |

====Lack of sufficient financing supply==== | ====Lack of sufficient financing supply==== | ||

| − | A main barrier to access funding is the lack of affordable long-term loans. OGS business models are considered very risky as they are quite new and have only a limited track-record which leads to investors expecting only low profits. Besides most of the local investors are not familiar with the credit risk analysis of OGS projects and are therefore skeptical whether a significant cash flow can be generated. Consequently, they are demanding high interest rates and rigid collateral requirements. Especially private local finance suppliers like commercial banks offer debts on extremely high interest rates. Furthermore, despite progress across the industry, factors like perception risk, complex fund design and the time frame required to get through regulatory compliance prevent the disbursement of concessional capital. Concessional funding is needed to unlock commercial investments by decreasing investment risks and to scale up the business. In general, a lack of subsidies, which are needed to close the viability gap of high development costs and the low-income of rural households, in the sector exists<ref name=":0">ACE TAF (2021b) ''Stand-Alone Solar Investment Map Nigeria''. Africa Clean Energy Technical Assistance Facility. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.ace-taf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Stand-Alone-Solar-Investment-Map-Nigeria.pdf</nowiki>.</ref><ref name=":2">Adamopoulou, E. ''et al.'' (2022) ''Benchmarking Africa’s Minigrid Report 2022''. AMDA. Available at: <nowiki>https://africamda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Benchmarking-Africa-Minigrids-Report-2022-Key-Findings.pdf</nowiki>.</ref><ref name=":3">GOGLA (2022) ''Nigeria country brief''. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/resource_docs/nigeria_country_brief_0.pdf</nowiki> (Accessed: 22 September 2022).</ref>. | + | A main barrier to access funding is the lack of affordable long-term loans. OGS business models are considered very risky as they are quite new and have only a limited track-record which leads to investors expecting only low profits. Besides most of the local investors are not familiar with the credit risk analysis of OGS projects and are therefore skeptical whether a significant cash flow can be generated. Consequently, they are demanding high interest rates and rigid collateral requirements. Especially private local finance suppliers like commercial banks offer debts on extremely high interest rates. Furthermore, despite progress across the industry, factors like perception risk, complex fund design and the time frame required to get through regulatory compliance prevent the disbursement of concessional capital. Concessional funding is needed to unlock commercial investments by decreasing investment risks and to scale up the business. In general, a lack of [[Subsidies|subsidies]], which are needed to close the viability gap of high development costs and the low-income of rural households, in the sector exists<ref name=":0">ACE TAF (2021b) ''Stand-Alone Solar Investment Map Nigeria''. Africa Clean Energy Technical Assistance Facility. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.ace-taf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Stand-Alone-Solar-Investment-Map-Nigeria.pdf</nowiki>.</ref><ref name=":2">Adamopoulou, E. ''et al.'' (2022) ''Benchmarking Africa’s Minigrid Report 2022''. AMDA. Available at: <nowiki>https://africamda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Benchmarking-Africa-Minigrids-Report-2022-Key-Findings.pdf</nowiki>.</ref><ref name=":3">GOGLA (2022) ''Nigeria country brief''. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/resource_docs/nigeria_country_brief_0.pdf</nowiki> (Accessed: 22 September 2022).</ref>. |

====Entrepreneurs are not ready to absorb finance==== | ====Entrepreneurs are not ready to absorb finance==== | ||

| − | Many OGS companies are not ready to raise or absorb external capital given their current scale of operations. Smaller companies have shown limited ability to evaluate investment needs and prepare for a capital raise process. Furthermore, smaller companies also have smaller financing needs that are often outside the minimum requirements of investors. Accordingly, companies find it more difficult to access finance, especially at an early stage<ref name=":0" />. Another barrier is the long and elaborate licensing process for mini grid developers. 80% of the compliance time is taken up by licensing, whereby | + | Many OGS companies are not ready to raise or absorb external capital given their current scale of operations. Smaller companies have shown limited ability to evaluate investment needs and prepare for a capital raise process. Furthermore, smaller companies also have smaller financing needs that are often outside the minimum requirements of investors. Accordingly, companies find it more difficult to access finance, especially at an early stage<ref name=":0" />. Another barrier is the long and elaborate licensing process for mini grid developers. 80% of the compliance time is taken up by licensing, whereby Nigeria has the lowest compliance time compared to other African countries. Unlike large-scale power distributors, mini grid developers have to go through the whole regulatory cycle for every 100kWs installed. OGS companies therefore are only operating under limited open market principles, which affects the investments, bankability and profitability<ref name=":2" />. |

====Currency risks==== | ====Currency risks==== | ||

| − | Inconsistencies in local currencies as well as foreign exchange rates lower the ability to absorb funding and manage import costs. Local currency lending is mostly disbursed and repaid in hard currency like dollar or euro, while debt services are fixed in local currencies. In the case of a devaluation or inconsistencies, for example through a pandemic, the borrowers may suffer financial loss. To reduce foreign exchange rate risks, the use of debt financing in local currency offers should be considered<ref>AFDB (2020b) ‘Local currency financing for off-grid energy solutions in Africa limited, needs scaling up - African Development Bank report’. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.afdb.org/fr/news-and-events/press-releases/local-currency-financing-grid-energy-solutions-africa-limited-needs-scaling-african-development-bank-report-39698</nowiki> (Accessed: 23 September 2022).</ref><ref>Hirschhofer, H. and Mittal, V. (2021) ''Africa’s shift to funding sustainable power in local currencies: The opportunity for ECAs''. Berne Union. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.tcxfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/p094-096-KN-Climate-TCX-and-AIDA.pdf</nowiki> (Accessed: 23 September 2022).</ref><ref name=":3" />. | + | Inconsistencies in local currencies as well as foreign exchange rates lower the ability to absorb funding and manage import costs. Local currency lending is mostly disbursed and repaid in hard currency like US dollar or euro, while debt services are fixed in local currencies. In the case of a devaluation or inconsistencies, for example through a pandemic, the borrowers may suffer financial loss. To reduce foreign exchange rate risks, the use of debt financing in local currency offers should be considered<ref>AFDB (2020b) ‘Local currency financing for off-grid energy solutions in Africa limited, needs scaling up - African Development Bank report’. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.afdb.org/fr/news-and-events/press-releases/local-currency-financing-grid-energy-solutions-africa-limited-needs-scaling-african-development-bank-report-39698</nowiki> (Accessed: 23 September 2022).</ref><ref>Hirschhofer, H. and Mittal, V. (2021) ''Africa’s shift to funding sustainable power in local currencies: The opportunity for ECAs''. Berne Union. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.tcxfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/p094-096-KN-Climate-TCX-and-AIDA.pdf</nowiki> (Accessed: 23 September 2022).</ref><ref name=":3" />. |

==Guiding Principles== | ==Guiding Principles== | ||

The following chapter provides guiding principles, consisting of solutions and examples, for the problems highlighted above. | The following chapter provides guiding principles, consisting of solutions and examples, for the problems highlighted above. | ||

| − | ====Target financing that is suitable for the | + | ====Target financing that is suitable for the maturity of your company==== |

When entrepreneurs are looking for funding, various aspects have to be taken into account. Depending on the business stage, a company needs different types of financing. Start-ups, with a high-risk profile, tend to rely mainly on grants. Once a project has received sufficient grant funding, it is financially viable for private sector funding and scaling-up<ref>REA (2016) ''Rural Electrification Strategy and Implementation Plan (RESIP)''. Federal Republic of Nigeria. Available at: <nowiki>http://rea.gov.ng/download/rural-electrification-strategy-implementation-plan-resip/</nowiki> (Accessed: 22 September 2022).</ref>. | When entrepreneurs are looking for funding, various aspects have to be taken into account. Depending on the business stage, a company needs different types of financing. Start-ups, with a high-risk profile, tend to rely mainly on grants. Once a project has received sufficient grant funding, it is financially viable for private sector funding and scaling-up<ref>REA (2016) ''Rural Electrification Strategy and Implementation Plan (RESIP)''. Federal Republic of Nigeria. Available at: <nowiki>http://rea.gov.ng/download/rural-electrification-strategy-implementation-plan-resip/</nowiki> (Accessed: 22 September 2022).</ref>. | ||

For scaling-up their operations developers need access to affordable debt as well as equity. As early-stage companies mostly have not been able to generate much capital, it is more difficult for them to prove their profitability and take out loans. Debt providers such as banks expect to see a track record of profitability in potential investees<ref>Yakubu, A. ''et al.'' (2018) ''Minigrid Investment Report - Scaling the Nigerian Market''. The Nigerian Economic Summit Group (NESG). Available at: <nowiki>https://rmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/RMI_Nigeria_Minigrid_Investment_Report_2018.pdf</nowiki>.</ref>. Concessional financing facilities including debts at subsidized interest rates or credit-risk guarantees, provided by development banks for commercial lenders, should be considered. Many different funding opportunities exist, which offer grant, equity and debt. Existing search platforms can help to find suitable offers and application documents quickly. | For scaling-up their operations developers need access to affordable debt as well as equity. As early-stage companies mostly have not been able to generate much capital, it is more difficult for them to prove their profitability and take out loans. Debt providers such as banks expect to see a track record of profitability in potential investees<ref>Yakubu, A. ''et al.'' (2018) ''Minigrid Investment Report - Scaling the Nigerian Market''. The Nigerian Economic Summit Group (NESG). Available at: <nowiki>https://rmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/RMI_Nigeria_Minigrid_Investment_Report_2018.pdf</nowiki>.</ref>. Concessional financing facilities including debts at subsidized interest rates or credit-risk guarantees, provided by development banks for commercial lenders, should be considered. Many different funding opportunities exist, which offer grant, equity and debt. Existing search platforms can help to find suitable offers and application documents quickly. | ||

| − | Impact equity investors are the most active investors in the Nigerian market. Due to their mostly smaller ticket size, they are especially suitable for new relatively nascent companies, as they are more willing to provide seed capital ( | + | Impact equity investors are the most active investors in the Nigerian market. Due to their mostly smaller ticket size, they are especially suitable for new relatively nascent companies, as they are more willing to provide seed capital<ref>USAID (2019) NPSP Nigeria Off-Grid Energy Market Intelligence Report. Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00XGH7.pdf (Accessed Sept 25, 2023).</ref>. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[File:Bildschirmfoto_2023-03-22_um_10.54.05.png|alt=|718x718px]] | ||

''Figure 1: SAS financing need at different stages of growth and operating models<ref name=":0" />'' | ''Figure 1: SAS financing need at different stages of growth and operating models<ref name=":0" />'' | ||

| Line 84: | Line 78: | ||

Most financing is going to international companies, partly because Nigerian-capital companies are relatively new (3-5 years). Capacity building can lead to more funds being mobilized. An ACE TAF study found that only 21% of surveyed solar technicians across Nigeria had any formal training on repair of solar products. | Most financing is going to international companies, partly because Nigerian-capital companies are relatively new (3-5 years). Capacity building can lead to more funds being mobilized. An ACE TAF study found that only 21% of surveyed solar technicians across Nigeria had any formal training on repair of solar products. | ||

| − | Another method to improve investment readiness and transparency is detailed financial management. Investors usually want to see statements about past and projected financial performance and expect transparency from companies. An adequate record of key financial and operational performance indicators is beneficial. Technical assistance, e.g. in the form of tools, can help to collect this data. To model and assess the economic viability of mini-grid investments, instruments such as MEI's financial feasibility assessment tool exist. By inputting all key data, the model shows the most important features and gives sufficient feedback to fully understand and analyse the economic performance of the target mini-grid project<ref name=":1">ACE TAF (2021a) ''Stand Alone Solar (SAS) Market Update: Nigeria''. Kenya: Africa Clean Energy Technical Assistance Facility. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.ace-taf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ACE-TAF-Stand-Alone-Solar-SAS-Market-Update-Nigeria.pdf</nowiki> (Accessed: 22 September 2022).</ref><ref name=":0" />. | + | Another method to improve investment readiness and transparency is detailed financial management. Investors usually want to see statements about past and projected financial performance and expect transparency from companies. An adequate record of key financial and operational performance indicators is beneficial. Technical assistance, e.g. in the form of tools, can help to collect this data. To model and assess the economic viability of mini-grid investments, instruments such as [[FATE Financial Assessment Tool for Electrification|MEI's financial feasibility assessment tool]] exist. By inputting all key data, the model shows the most important features and gives sufficient feedback to fully understand and analyse the economic performance of the target mini-grid project<ref name=":1">ACE TAF (2021a) ''Stand Alone Solar (SAS) Market Update: Nigeria''. Kenya: Africa Clean Energy Technical Assistance Facility. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.ace-taf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ACE-TAF-Stand-Alone-Solar-SAS-Market-Update-Nigeria.pdf</nowiki> (Accessed: 22 September 2022).</ref><ref name=":0" />. |

'''<u>Example:</u>''' | '''<u>Example:</u>''' | ||

| − | There are several finances existing, which provide technical assistance or capacity building support, to ensure an efficient management of the funding the companies raised (i.e. All On Hub, AECF). | + | There are several finances existing, which provide technical assistance or capacity building support, to ensure an efficient management of the funding the companies raised (i.e. All On Hub, AECF). [http://creedsenergy.com/en/ CREEDS Energy], a Solar Home System (SHS) developer established in 2012, won the Nigerian Off-Grid Energy Challenge among others in the SHS category in 2018. In addition to funding, technical assistance by the United States African Development Fund (USADF) and governance support from the impact investment company All On was provided. Through the technical assistance CREEDS was able to develop a financing application. In 2021, CREEDS signed the Output-Based Fund agreement with REA under the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP). The grant that CREEDS has received helped to leverage other financial resources for scaling-up<ref>Uzoho, P. (2018) ''Ten Off-grid Energy Companies Selected for USADF Funding'', ''This Day''. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2018/10/18/ten-off-grid-energy-companies-selected-for-usadf-funding/</nowiki> (Accessed: 26 September 2022).</ref>. |

| + | |||

| + | ==== Project financing through carbon finance ==== | ||

| + | [[Carbon Finance|Carbon finance]] is a way for entrepreneurs to generate an additional source of revenue by creating a commercial value for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This so-called carbon finance can be accessed by implementing a project under the requirements of the '''[https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-kyoto-protocol/mechanisms-under-the-kyoto-protocol/the-clean-development-mechanism Clean Development Mechanism] (CDM)''' of the Kyoto Protocol or for the '''Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) that generates carbon credits.''' | ||

| − | = | + | The VCM is a market mechanism that enables businesses, governments, and individuals to purchase carbon credits to offset their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions voluntarily. These carbon credits are generated by projects that reduce or remove emissions, such as renewable-energy projects <ref name=":5">USAID (2023). Carbon Credits for Off-grid Solar in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://scms.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/Power-Africa-Carbon-Credits-for-OGS-Companies.pdf</ref>. To expand Africa's share of the global carbon-credit market, the [https://africacarbonmarkets.org/ Africa Carbon Markets Initiative] (ACMI) was launched in 2022. Off-grid solar firms can participate in Africa's VCM in many ways. One approach is to create their own carbon projects, which, though involving a longer timeline and higher initial costs, can minimize risks once carbon credits are issued. Alternatively, companies can join data-driven carbon programs like CarbonClear, leveraging real-time consumption data from pay-as-you-go-enabled devices for a quicker and more cost-effective entry into the carbon market. However, standards from the International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance do not currently recognize digital strategies to participate in the VCM. Consequently, companies must consider trade-offs to select a model aligned with their financial situation, installation portfolio, and market preferences<ref name=":5" />. |

| − | |||

| − | [ | ||

| − | + | ==== Results-based financing (RBF) ==== | |

| + | [[Results-Based Financing|RBF]] is a public funding mechanism by which disbursements by a funder to a recipient are conditional on the achievement of predetermined results. It involves three key features: (i) payments are made when the pre-agreed results have been achieved, (ii) the recipient has agency over how to achieve these results, and (iii) results need to be independently verified to cause a payment <ref>GOGLA (2023). Unlocking Off-Grid Solar: How Results-Based Financing is driving energy access and powering productivity. https://www.gogla.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/How-Results-Based-Financing-is-driving-energy-access-and-powering-productivity.pdf</ref>. | ||

| − | + | RBF is a way for the private sector to leverage funding from governments and development partners to achieve development goals, such as increasing access to electricity. Over the past decade, RBF programmes have been piloted, scaled up and diversified in the energy access sector. In Nigeria, it became a common mode of grant disbursement which is used under the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP) and the REF <ref>GIZ (2021). Nigeria Financing Instruments for the Mini-Grid Market. GET.transform. https://www.get-transform.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Success-in-Rural-Electrification-Case-Study_Nigeria.pdf</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==== | + | ==Existing tools== |

| − | + | {| class="wikitable" | |

| − | + | |+ | |

| + | !Name | ||

| + | !Nigeria specific | ||

| + | !Open source | ||

| + | !Description | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[FATE Financial Assessment Tool for Electrification|FATE - '''Financial Assessment Tool for Electrification''']] | ||

| + | |Yes | ||

| + | |Yes | ||

| + | |PeopleSuN's project partner [https://www.microenergy-international.com/ MEI] developed the FATE tool which is designed to establish the financial viability of mini grid and solar home system (SHS) projects in rural areas of Nigeria. This tool is addressed to companies, project developers, financiers, and policy makers. It is elaborated in a dynamic format, linking all inputs and outputs together, making it easy for the end-user to evaluate electrification projects according to different criteria including: revenues, expenses, and company's financial situation. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''[[Financing Sources Database|Financing Sources Database]]''' | ||

| + | |Yes | ||

| + | |Yes | ||

| + | |The Financing Sources Database provides an overview of existing opportunities for grant, equity, and debt financing or a mix of these. The sources are classified by the type of financing as well as the technological scope, target beneficiaries and geographical scope. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[https://www.usaid.gov/energy/mini-grids/financing USAID Mini-Grids Support Toolkit] | ||

| + | |No | ||

| + | |Yes | ||

| + | |The toolkit includes one module that focuses on challenges and needs in financing mini-grids. It explains (1) different sources of capital for mini-grid projects, (2) financial instruments that are available to cover the costs of building a mini-grid, (3) what sources of grants or concessional financing exist to help with mini-grids in developing countries, and (4) who will finance the needed upgrades to the main grid if mini-grids are integrated with the centralized grid. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[https://bridge.gogla.org/ GOGLA Bridge] | ||

| + | |No | ||

| + | |Yes | ||

| + | |The GOGLA Bridge is a database for GOGLA members and the broader stand-alone solar product sector providing an overview of support services for incubating and accelerating the growth of off-grid solar companies. Users can easily access information about grants, awards and competitions as well as details on relevant financing institutions and crowdfunding opportunities. The database has been developed with support from GET.invest. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | * | ||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

</div><!-- End .NIGERIA--> | </div><!-- End .NIGERIA--> | ||

[[Category:Nigeria Off-Grid Solar Knowledge Hub]] | [[Category:Nigeria Off-Grid Solar Knowledge Hub]] | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

| + | [[Category:Nigeria]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Solar]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Financing Solar]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Mini-grid]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Solar Home Systems (SHS)]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Rural Electrification]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Off-grid]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:44, 9 January 2024

Introduction

With only about 55% of the population having access to electricity[1], Nigeria is an attractive market for off-grid solar companies. This section will outline the challenges standalone solar (SAS) and mini grid developers face while accessing finance for their businesses, and provide some guidance on what can be done to tackle these.

This section will firstly describe different key components of financing. Afterwards, three challenges of accessing finance are highlighted, followed by three different guiding principles, each of them illustrated by practical examples from established companies. Please keep in mind that this section focuses on business financing and how to access finance for your company. Accessing finance is only one part of a successful business model. For more details on this area, please also consult the Design Business Model section.

The following video gives an overview of different financing opportunities by the Nigerian Electrification Program for the clean energy sector:

Definitions

There are three funding sources that should be considered when searching for financing options in the off-grid sector. This chapter will give an overview of the most common options. Which options are most suitable for which company stage, will be discussed in detail later in the chapter “Target financing that is suitable for the maturity of your company”.

Grant

A grant is a non-repayable award, mostly offered by governments or donors. Companies usually have to face a selection process in a competition with other applicants.

Equity

Investors are buying shares of the company in order to make money through dividends or by selling their stakes.

Debt

Unlike grants, debts are borrowed funds which have to be repaid plus the amount of interest. Debt finance is the main used instrument in the SAS and mini grid sector.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Individual Financing | Developer is raising the fund through the company's available cashflow. Not a common method because of the high capital costs needed. |

| Third Party Financing | Developer is seeking funding from external sources. External funding includes grants, loans from banks and equity from impact investors or DFIs. Common financing method for capital intensive projects. |

| Blended Financing | Developer is combining external and internal financing in the form of funds which are raised from the company's cashflow. Usual method with grants when the developer has to raise counterpart funding. |

Challenges in raising finance

The off-grid electrification sector is growing and attracting more investments and financing. However, there are still difficulties in accessing funding, especially for smaller companies which have been unable to raise equity. Therefore, most of the funding flows to already established, large companies. This section focuses on the main challenges off-grid solar (OGS) enterprises face when raising finance.

Lack of sufficient financing supply

A main barrier to access funding is the lack of affordable long-term loans. OGS business models are considered very risky as they are quite new and have only a limited track-record which leads to investors expecting only low profits. Besides most of the local investors are not familiar with the credit risk analysis of OGS projects and are therefore skeptical whether a significant cash flow can be generated. Consequently, they are demanding high interest rates and rigid collateral requirements. Especially private local finance suppliers like commercial banks offer debts on extremely high interest rates. Furthermore, despite progress across the industry, factors like perception risk, complex fund design and the time frame required to get through regulatory compliance prevent the disbursement of concessional capital. Concessional funding is needed to unlock commercial investments by decreasing investment risks and to scale up the business. In general, a lack of subsidies, which are needed to close the viability gap of high development costs and the low-income of rural households, in the sector exists[3][4][5].

Entrepreneurs are not ready to absorb finance

Many OGS companies are not ready to raise or absorb external capital given their current scale of operations. Smaller companies have shown limited ability to evaluate investment needs and prepare for a capital raise process. Furthermore, smaller companies also have smaller financing needs that are often outside the minimum requirements of investors. Accordingly, companies find it more difficult to access finance, especially at an early stage[3]. Another barrier is the long and elaborate licensing process for mini grid developers. 80% of the compliance time is taken up by licensing, whereby Nigeria has the lowest compliance time compared to other African countries. Unlike large-scale power distributors, mini grid developers have to go through the whole regulatory cycle for every 100kWs installed. OGS companies therefore are only operating under limited open market principles, which affects the investments, bankability and profitability[4].

Currency risks

Inconsistencies in local currencies as well as foreign exchange rates lower the ability to absorb funding and manage import costs. Local currency lending is mostly disbursed and repaid in hard currency like US dollar or euro, while debt services are fixed in local currencies. In the case of a devaluation or inconsistencies, for example through a pandemic, the borrowers may suffer financial loss. To reduce foreign exchange rate risks, the use of debt financing in local currency offers should be considered[6][7][5].

Guiding Principles

The following chapter provides guiding principles, consisting of solutions and examples, for the problems highlighted above.

Target financing that is suitable for the maturity of your company

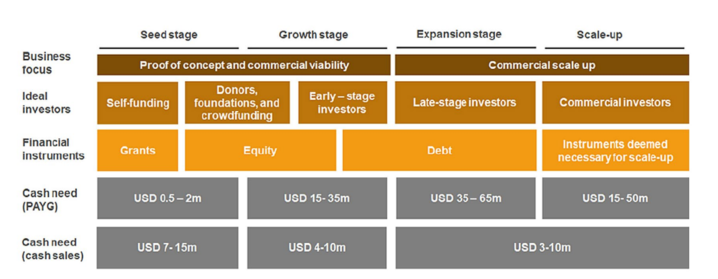

When entrepreneurs are looking for funding, various aspects have to be taken into account. Depending on the business stage, a company needs different types of financing. Start-ups, with a high-risk profile, tend to rely mainly on grants. Once a project has received sufficient grant funding, it is financially viable for private sector funding and scaling-up[8].

For scaling-up their operations developers need access to affordable debt as well as equity. As early-stage companies mostly have not been able to generate much capital, it is more difficult for them to prove their profitability and take out loans. Debt providers such as banks expect to see a track record of profitability in potential investees[9]. Concessional financing facilities including debts at subsidized interest rates or credit-risk guarantees, provided by development banks for commercial lenders, should be considered. Many different funding opportunities exist, which offer grant, equity and debt. Existing search platforms can help to find suitable offers and application documents quickly.

Impact equity investors are the most active investors in the Nigerian market. Due to their mostly smaller ticket size, they are especially suitable for new relatively nascent companies, as they are more willing to provide seed capital[10].

Figure 1: SAS financing need at different stages of growth and operating models[3]

Example:

The Green Village Energy (GVE) project is the largest mini grid developer in Nigeria. Electricity is distributed to communities through a network of retailers. Before GVE received its first grant, the company raised its first round of investment through family and friends. Subsequently, the company received funding in the form of grants from REA, USADF and the USAID Power Africa programme, which also provided transaction advisory support. Furthermore it received loans from the Bank of Industry, which is now a shareholder, and equity as well as debt funding through the impact investor All-On. Although GVE has already received a lot of funding, it has not been able to access credit from local commercial banks due to high interest rates[11]. For further information to GVE see also the case study.

Consider both foreign currency and local currency financing

The Nigerian market for off-grid solar products is mainly driven by foreign investors. In the meantime, there is an increasing number of local financing options, such as commercial banks or government funding for example through REA. Developers often require hard currency finance in order to pay for their equipment imports. However, this may be accompanied by a potential shortage of foreign exchange. Foreign currency risks can be mitigated through the use of local currency debts, but these are often characterized by higher interest rates. Because of the unaffordability of local currency debt finance, companies are reliant on equity finance. When selecting suitable funding, both local and foreign currencies must be taken into account[11].

Example:

The African Development Bank (AfDB) launched with the European Union the DESCOs financing programme in 2018. The programme aims to remove barriers to accessing finance and support growth and expansion into new markets. For this purpose, access to local currency will be facilitated by providing risk mitigation tools to local lenders. This includes partial credit guarantees (PCG) which cover a part of the debt that companies receive from their lenders and credit enhancements which allow the local finance institutions to provide more favorable long-term debts[12][13].

Exploit all opportunities for capacity building and technical assistance

Most financing is going to international companies, partly because Nigerian-capital companies are relatively new (3-5 years). Capacity building can lead to more funds being mobilized. An ACE TAF study found that only 21% of surveyed solar technicians across Nigeria had any formal training on repair of solar products.

Another method to improve investment readiness and transparency is detailed financial management. Investors usually want to see statements about past and projected financial performance and expect transparency from companies. An adequate record of key financial and operational performance indicators is beneficial. Technical assistance, e.g. in the form of tools, can help to collect this data. To model and assess the economic viability of mini-grid investments, instruments such as MEI's financial feasibility assessment tool exist. By inputting all key data, the model shows the most important features and gives sufficient feedback to fully understand and analyse the economic performance of the target mini-grid project[14][3].

Example:

There are several finances existing, which provide technical assistance or capacity building support, to ensure an efficient management of the funding the companies raised (i.e. All On Hub, AECF). CREEDS Energy, a Solar Home System (SHS) developer established in 2012, won the Nigerian Off-Grid Energy Challenge among others in the SHS category in 2018. In addition to funding, technical assistance by the United States African Development Fund (USADF) and governance support from the impact investment company All On was provided. Through the technical assistance CREEDS was able to develop a financing application. In 2021, CREEDS signed the Output-Based Fund agreement with REA under the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP). The grant that CREEDS has received helped to leverage other financial resources for scaling-up[15].

Project financing through carbon finance

Carbon finance is a way for entrepreneurs to generate an additional source of revenue by creating a commercial value for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This so-called carbon finance can be accessed by implementing a project under the requirements of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the Kyoto Protocol or for the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) that generates carbon credits.

The VCM is a market mechanism that enables businesses, governments, and individuals to purchase carbon credits to offset their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions voluntarily. These carbon credits are generated by projects that reduce or remove emissions, such as renewable-energy projects [16]. To expand Africa's share of the global carbon-credit market, the Africa Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI) was launched in 2022. Off-grid solar firms can participate in Africa's VCM in many ways. One approach is to create their own carbon projects, which, though involving a longer timeline and higher initial costs, can minimize risks once carbon credits are issued. Alternatively, companies can join data-driven carbon programs like CarbonClear, leveraging real-time consumption data from pay-as-you-go-enabled devices for a quicker and more cost-effective entry into the carbon market. However, standards from the International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance do not currently recognize digital strategies to participate in the VCM. Consequently, companies must consider trade-offs to select a model aligned with their financial situation, installation portfolio, and market preferences[16].

Results-based financing (RBF)

RBF is a public funding mechanism by which disbursements by a funder to a recipient are conditional on the achievement of predetermined results. It involves three key features: (i) payments are made when the pre-agreed results have been achieved, (ii) the recipient has agency over how to achieve these results, and (iii) results need to be independently verified to cause a payment [17].

RBF is a way for the private sector to leverage funding from governments and development partners to achieve development goals, such as increasing access to electricity. Over the past decade, RBF programmes have been piloted, scaled up and diversified in the energy access sector. In Nigeria, it became a common mode of grant disbursement which is used under the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP) and the REF [18].

Existing tools

| Name | Nigeria specific | Open source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| FATE - Financial Assessment Tool for Electrification | Yes | Yes | PeopleSuN's project partner MEI developed the FATE tool which is designed to establish the financial viability of mini grid and solar home system (SHS) projects in rural areas of Nigeria. This tool is addressed to companies, project developers, financiers, and policy makers. It is elaborated in a dynamic format, linking all inputs and outputs together, making it easy for the end-user to evaluate electrification projects according to different criteria including: revenues, expenses, and company's financial situation. |

| Financing Sources Database | Yes | Yes | The Financing Sources Database provides an overview of existing opportunities for grant, equity, and debt financing or a mix of these. The sources are classified by the type of financing as well as the technological scope, target beneficiaries and geographical scope. |

| USAID Mini-Grids Support Toolkit | No | Yes | The toolkit includes one module that focuses on challenges and needs in financing mini-grids. It explains (1) different sources of capital for mini-grid projects, (2) financial instruments that are available to cover the costs of building a mini-grid, (3) what sources of grants or concessional financing exist to help with mini-grids in developing countries, and (4) who will finance the needed upgrades to the main grid if mini-grids are integrated with the centralized grid. |

| GOGLA Bridge | No | Yes | The GOGLA Bridge is a database for GOGLA members and the broader stand-alone solar product sector providing an overview of support services for incubating and accelerating the growth of off-grid solar companies. Users can easily access information about grants, awards and competitions as well as details on relevant financing institutions and crowdfunding opportunities. The database has been developed with support from GET.invest. |

Bibliography

- ↑ IEA et al. (2020) Tracking SDG 7: Nigeria. Available at: https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/country/nigeria (Accessed: 23 September 2022).

- ↑ USAID and Power Africa (2022) PA NPSP Off-Grid Market Intelligence Report. Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00ZB5X.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 ACE TAF (2021b) Stand-Alone Solar Investment Map Nigeria. Africa Clean Energy Technical Assistance Facility. Available at: https://www.ace-taf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Stand-Alone-Solar-Investment-Map-Nigeria.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Adamopoulou, E. et al. (2022) Benchmarking Africa’s Minigrid Report 2022. AMDA. Available at: https://africamda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Benchmarking-Africa-Minigrids-Report-2022-Key-Findings.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 GOGLA (2022) Nigeria country brief. Available at: https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/resource_docs/nigeria_country_brief_0.pdf (Accessed: 22 September 2022).

- ↑ AFDB (2020b) ‘Local currency financing for off-grid energy solutions in Africa limited, needs scaling up - African Development Bank report’. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/fr/news-and-events/press-releases/local-currency-financing-grid-energy-solutions-africa-limited-needs-scaling-african-development-bank-report-39698 (Accessed: 23 September 2022).

- ↑ Hirschhofer, H. and Mittal, V. (2021) Africa’s shift to funding sustainable power in local currencies: The opportunity for ECAs. Berne Union. Available at: https://www.tcxfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/p094-096-KN-Climate-TCX-and-AIDA.pdf (Accessed: 23 September 2022).

- ↑ REA (2016) Rural Electrification Strategy and Implementation Plan (RESIP). Federal Republic of Nigeria. Available at: http://rea.gov.ng/download/rural-electrification-strategy-implementation-plan-resip/ (Accessed: 22 September 2022).

- ↑ Yakubu, A. et al. (2018) Minigrid Investment Report - Scaling the Nigerian Market. The Nigerian Economic Summit Group (NESG). Available at: https://rmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/RMI_Nigeria_Minigrid_Investment_Report_2018.pdf.

- ↑ USAID (2019) NPSP Nigeria Off-Grid Energy Market Intelligence Report. Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00XGH7.pdf (Accessed Sept 25, 2023).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 AFDB (2020a) Exploring the Role of Guarantee Products in Supporting Local Currency Financing of Sustainable Off-Grid Energy Projects in Africa. Côte d’Ivoire: The African Development Bank. Available at: https://africa-energy-portal.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/Local%20Currency%20Financing%20of%20Off-Grid%20Renewable%20Energy%20Projects%20in%20Africa%20Report.pdf.

- ↑ Ben Abda, F. and Miyares, N. (2019) ‘De-risking the off-grid space with innovative financial solutions’, Africa Energy Portal. Available at: https://africa-energy-portal.org/blogs/de-risking-grid-space-innovative-financial-solutions (Accessed: 26 September 2022).

- ↑ Mpoke-Bigg, A. (2019) ‘African Development Bank approves new financing program for energy providers, 4.5 mln people in sub-Saharan Africa to benefit from off-grid power by 2025’, African Development Bank Group. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/african-development-bank-approves-new-financing-program-energy-providers-45-mln-people-sub-saharan-africa-benefit-grid-power-2025-25545 (Accessed: 26 September 2022).

- ↑ ACE TAF (2021a) Stand Alone Solar (SAS) Market Update: Nigeria. Kenya: Africa Clean Energy Technical Assistance Facility. Available at: https://www.ace-taf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ACE-TAF-Stand-Alone-Solar-SAS-Market-Update-Nigeria.pdf (Accessed: 22 September 2022).

- ↑ Uzoho, P. (2018) Ten Off-grid Energy Companies Selected for USADF Funding, This Day. Available at: https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2018/10/18/ten-off-grid-energy-companies-selected-for-usadf-funding/ (Accessed: 26 September 2022).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 USAID (2023). Carbon Credits for Off-grid Solar in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://scms.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/Power-Africa-Carbon-Credits-for-OGS-Companies.pdf

- ↑ GOGLA (2023). Unlocking Off-Grid Solar: How Results-Based Financing is driving energy access and powering productivity. https://www.gogla.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/How-Results-Based-Financing-is-driving-energy-access-and-powering-productivity.pdf

- ↑ GIZ (2021). Nigeria Financing Instruments for the Mini-Grid Market. GET.transform. https://www.get-transform.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Success-in-Rural-Electrification-Case-Study_Nigeria.pdf