Difference between revisions of "Result Based Monitoring of Cookstove Projects"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

== '''Introduction to Results Based Monitoring (RBM)''' == | == '''Introduction to Results Based Monitoring (RBM)''' == | ||

| − | Results Based Monitoring is an international monitoring standard developed and agreed by the OECD DAC (Development Assistance Committee <font size="2">of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)</font> to monitor development results. Results are defined as development changes that follow directly from an intervention; they can be outputs, outcomes or impacts (intended or unintended, positive and/or negative) resulting from a development intervention. According to the OECD-DAC definition, results occur as causal sequences from a development intervention towards the desired objectives. Results Based Monitoring is a method to examine the result hypotheses in a empirical and systematic way.<br> | + | Results Based Monitoring is an international monitoring standard developed and agreed by the OECD DAC (Development Assistance Committee <font size="2">of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)</font> to monitor development results. Results are defined as development changes that follow directly from an intervention; they can be outputs, outcomes or impacts (intended or unintended, positive and/or negative) resulting from a development intervention. According to the OECD-DAC definition, results occur as causal sequences from a development intervention towards the desired objectives. Results Based Monitoring is a method to examine the result hypotheses in a empirical and systematic way.<br> |

'''<font size="2">Additional Information </font>''' | '''<font size="2">Additional Information </font>''' | ||

| − | + | [http://www.endev.info/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=260&&Itemid=13 GTZ (2008): Wirkungsorientiertes Monitoring Leitfaden für die Technische Zusammenarbeit (deutsch)] | |

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

== '''Results chains''' == | == '''Results chains''' == | ||

Revision as of 11:08, 22 December 2008

--> Back to Overview Compendium

Why monitor?

Projects introduce development changes to make a difference to the lives of target groups. They strive to achieve positive change, and it is essential for them to monitor and evaluate the causal chain from project activity to impacts if they are to prove the value of their project. This information is needed for both project management and for reporting to the outside world (e.g. a partner or donor).

Results Based Monitoring (RBM) serves different purposes:

- To check that set targets have been met

- To provide data and information for reviewing the strategy

- To steer and make changes, where necessary, to an intervention

- To create ownership among various project actors

- To provide evidence on progress/ changes/ achievements for national partners (e.g. ministries).

Results Based Monitoring requires time, personnel and funds, and thus it needs to be included into the activities and budget plan. Ideally, Results Based Monitoring should be planned from the very beginning of a project (concept development, activity planning, budgeting etc.) to ensure that it is an integral part of the approach. Often, however, it is only considered at a later stage. It is important to allocate enough resources (working time, finances) into the budget, and to plan it carefully so that it delivers useful results.

Introduction to Results Based Monitoring (RBM)

Results Based Monitoring is an international monitoring standard developed and agreed by the OECD DAC (Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) to monitor development results. Results are defined as development changes that follow directly from an intervention; they can be outputs, outcomes or impacts (intended or unintended, positive and/or negative) resulting from a development intervention. According to the OECD-DAC definition, results occur as causal sequences from a development intervention towards the desired objectives. Results Based Monitoring is a method to examine the result hypotheses in a empirical and systematic way.

Additional Information

GTZ (2008): Wirkungsorientiertes Monitoring Leitfaden für die Technische Zusammenarbeit (deutsch)

Results chains

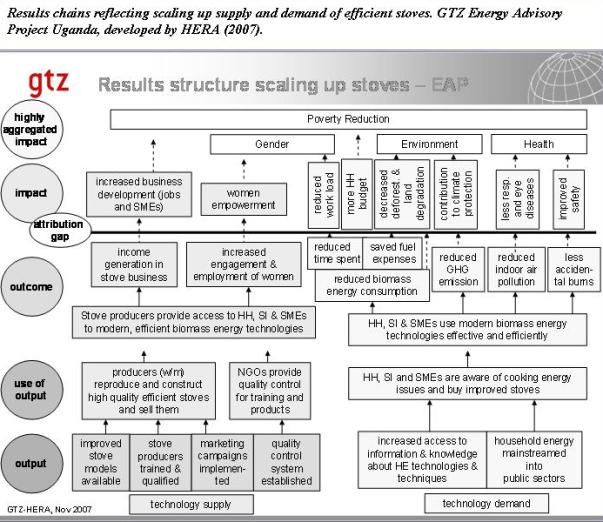

The basis of Results Based Monitoring is the results chain, which describes how a development intervention, through a step-by-step process, contributes to development results. The intervention starts with the inputs used to perform activities, and these lead to the outputs of the project. These outputs, which are used by target groups or intermediaries, lead to outcomes and impacts. In most cases, it is relatively easy to attribute changes, up to the level that identifies the uses of the output.

Beyond this, climbing up to the levels of ‘outcome’ and ‘impact’, external factors influence whether the intended results can be achieved. These external factors can only be controlled or influenced to a certain extent (if at all) by the project or programme. Whether the objectives are met no longer depends solely on the performance of the project, but depends on all the actors and external factors involved. Therefore, achievements are only attributable to the intervention up to a certain level – called the ‘outcome’. Beyond the outcome, effects can no longer be directly linked to this one development intervention. The attribution gap widens at the stage where changes, although observed in the target area, cannot be solely related to project outputs.

Up to where a causal relation between outputs and observed development changes can be demonstrated, projects are entitled to claim the observed development changes as an ‘outcome’ of their activities. Project and programme objectives or targets are set at this level. Beyond the outcome level, projects and programmes aim at further impacts, which are usually the ultimate reason for the intervention.

In most cases it is not possible to bring the ‘impact’ into a causal relation, as too many actors are involved to isolate clearly the effect of a single intervention. Nonetheless, the project should seek to address and verify the contribution of the project impacts against highly aggregated development results (as, for instance, the Millennium Development Goals, MDGs). Even though full-scale attribution cannot be done, GTZ expects its managers to provide plausible hypotheses on the projects contributions to high-level development results (Figure).

Thus, the results chain describes the necessary sequence that a development intervention must take to achieve the desired objectives:

- Inputs to implement activities

- Activities that generate outputs

- Outputs used by target groups, leading to outcomes (which are the objective of the development intervention)

- Outcomes contribute to the impacts

GTZ monitors results regularly up to outcome level. Beyond this level, it demonstrates the contribution to impacts through plausibility and impact assessments.

Examples of results chains for cooking energy projects

The following example of a cooking energy intervention ‘Scaling up of improved biomass stoves’ shows two main chains:

- for stove supply; targeted at producers and traders

- for stove demand; targeting users and the public sector.

Input is not mentioned here, but comprises all the resources provided by all partners: donor organisations, implementers, government partners (money, personnel and material).

Activities that particularly target stove supply include: technology development, training of trainers and producers, marketing, and quality control. Activities focused on stove demand include: mainstreaming cooking energy in the public sector, information and awareness campaigns. They could include establishment of a credit scheme, although this activity is not shown on the table as it was not relevant in this project.

The production outputs of the interventions comprise: improved stove models available, producers trained and qualified, marketing campaigns implemented and quality control system established. This leads to a well-established production and promotion stove initiative, and more stoves on the market.

On the consumption side: the outputs include: increased access to information and knowledge, and household energy mainstreamed into the public sector. This results in more awareness and higher probability of purchase.

Between the output and the use of output lies the system boundary of the project. Up to this point, the project is directly influencing the results; thereafter the success of the intervention is influenced by the targeted groups and their behaviour. But the project is still responsible for achieving results, and therefore the importance of participation and ownership of the target groups becomes very crucial.

The increaseduse of the output, in this case improved biomass stoves, depends on the future users, the project environment and the levels of promotion provided by producers and sales personnel. Support to manufacturers and supplies should be established, or strengthened, by the project.

The outcome of the whole exercise is an increase in access to modern cooking energy technologies. This is the target of the Energy Advisory Project. It enables stove producers to sell their technologies, to generate income and to facilitate the increased involvement of women. Provided that the users cook effectively and efficiently with their new stoves, there will be reduced biomass consumption, a positive impact on time and money, and a reduction in GHG emissions, indoor air pollution, and accidents.

Further results beyond the outcome are not isolated and cannot be attributed to only one project. This is where the attribution gap between outcomes and impacts is located. Impacts are the positive and negative, primary and secondary long-term effects produced by a development intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended. Positive impacts are for example less deforestation, less disease, improved working conditions and more jobs and small/medium enterprises (SMEs) created. A negative impact might be less time for social interaction of women during firewood collection. Where the impacts of scaling up improved biomass stoves finally contribute to the MDGs, they are described as highly aggregated impacts.

Results Based Monitoring is intended to measure the progress and success of the project towards achieving its objectives. To measure this progress, indicators have to be developed. They are quantitative or qualitative values that describe the real situation, and indicate the degree of change. Ideally, these indicators will be measured at the beginning of the project (baseline), during the project, at the end of the project, and perhaps several years later.

The baseline describes the situation prior to the development intervention. It provides a basis against which to monitor whether the intervention has achieved the desired results. Through indicators, project managers are able to trace back the achievement of set targets, to identify unexpected changes, and to identify unintended impacts. It is possible to determine whether outputs achieved have really proved useful, and whether their use has really lead to a worthwhile outcome in development terms. If necessary, the project strategy can be adjusted, additional activities can be included, or further key stakeholders can be involved.

Additional information

- Results chain Ethiopia

- Results chain Kenya

- GTZ (1996) – Measuring Successes and Setbacks. How to Monitor and Evaluate Household Energy Projects

- GTZ (May 2004)– Results-based Monitoring. Guidelines for Technical Cooperation Projects and Programmes

- OECD/DAC (2002) – Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results Based Management

- UNDP (August 2005) - ‘Energizing the Millennium Development Goals‘

- UN Energy (July 2005) - ‘The energy challenge for achieving the Millennium Development Goals

- GVEP M&EED Group (2006) - A Guide to Monitoring and Evaluation for Energy Projects

For setting up Results Based Monitoring for Energy projects compare http://www.gvepinternational.org/gvep_knowledge_base/monitoring__evaluation This Guide proposes a step by step approach to building project-specific M&E procedures. The guide is intended for energy access projects, which don’t have already donor or stakeholder determined M&E methods. The guide was developed by the International Working Group on Monitoring and Evaluation in Energy for Development (M&EED) - Boiling Point No 55 (June 2008) [http://www.hedon.info/BoilingPoint55-June2008 http://www.hedon.info/BoilingPoint55-June2008] -

Outcome-based monitoring

Each project can be monitored for several factors:

- Levels of output

- Increased capacity of producers

- Quality control systems

- Levels of marketing and promotion

- Increased levels of information and knowledge

To measure the use of the outputs, one would measure the production figures, quality and sales of stoves as well as purchase and awareness of households, social institutions, and SMEs.

To describe the outcomes (depending on the objective of the intervention), all information about access to cooking energy services would be monitored. In this instance, people with access to modern and clean cooking energy would be monitored by sales or construction figures, as well as monitoring correct usage by households, social institutions and SMEs.

The two key outcomes are usually considered to be the reduction of biomass energy consumption, and the reduction in indoor air pollution. Technologies are generally selected by the quality of their performance, efficiency and emission reduction as well as affordability. Tests are conducted in laboratories and at project sites, but of greater importance is the performance under ‘real’ conditions in households, social institutions and SMEs.

The stove’s properties will very much depend on the capacity of the user to achieve maximum efficiency and emission reduction. Users are given kitchen and firewood management training as part of each cooking energy intervention, acquiring knowledge about effective cooking techniques. Projects randomly monitor the in-house performance of stoves: many follow standardised testing procedures. Currently GTZ HERA is coordinating a collection and review of these tests to enable it to provide comparable testing procedures for all projects.

Impacts and Impact assessment

Cooking energy projects that enable access to improved energy, contribute to the MDGs. A plausible hypothesis on the project’s positive impacts to the MDGs should be provided, even though these impacts cannot be monitored, and thus cannot be attributed directly to the intervention.

One to five years after the intervention has been implemented, and when communities have had a chance to use the outputs, it can be worthwhile to do an impact assessment to determine whether the assumptions/ hypotheses on which the project was based have achieved the intended impacts (MDGs).

In these impact assessments, the very specific outcomes are monitored and compared with the baseline. These impacts include; income generated, women engaged in new activities, time and expenses saved, reductions in the levels of indoor air pollution, and reduction in the number of accident, relative to the baseline. They can be directly linked to project interventions. Their contribution to the achievement of impacts, such as increased business development, women’s empowerment, decreased deforestation, decreased respiratory and eye diseases, and finally to the MDGs is assessed and plausibly demonstrated. (It might not always be relevant to carry out an impact assessment and demonstrate relevant impacts within the region where the baseline study was undertaken. This is particularly true with nationwide programmes, or with projects that adopt a market-driven approach.)

Impact assessments have recently been carried out for cooking energy projects in Uganda, Malawi, and Ethiopia. The findings are impressive. Further studies are currently being implemented in Kenya and Bolivia (2008).

Impacts assessment – Methodology and tools

To collect empirical data on the impacts of energy projects, a wide range of methods and approaches is available. These may differ significantly in terms of time, money and expertise needed for implementation. The methods described in the following sections are recommended for measuring energy-related project impacts.

Generally, methodologies can be divided into quantitative and qualitative methods. Whereas quantitative approaches are concerned to quantify social phenomena by collecting and analysing numerical data, qualitative methods emphasise personal experience and interpretation. (Also qualitative data can be quantified e.g. counting the numbers of people who have expressed the same opinion.)

a) Quantitative Sample Survey

Structured sample surveys are a good way to obtain quantitative information on the life quality of small groups (called ‘sampling units’) such as households, social institutions and SMEs. Scheduled-structured interviews are the most common form in impact assessments. The questions, their wording and their sequence are fixed within a structured questionnaire and identical for every respondent. Beside standardized information, additional qualitative information can be gathered by the use of open questions.

b) Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative interviews are well suited to reveal background information and detailed opinions regarding particular themes. This type of interview is generally conducted for a small number of sampling units. It is advisable to make use of semi-structured questionnaires containing several open questions.

c) Focus Group Discussions

Focus Group Discussions are one type of qualitative method, allowing interviewers to study people in a more natural setting than in a one-to-one interview. Focus Group Discussions are low in cost, one can get results relatively quickly, and they provide several opinions by talking to several people at once. Care must be taken during these discussions to ensure that those who make the most noise do not dominate the groups with their views.

d) Observations

Observation of the target groups, villages and project interventions through local field staff is a cheap and simple way of gaining a first impression of energy impacts. Even though not as accurate and representative as structured surveys, observations can be especially useful for preparing further scientific research (e.g. questionnaires) by providing site-specific knowledge.

e) Document and Statistics Review

Besides information that needs to be gathered from interviews or observations, data on particular indicators might be readily available from local databases, statistics and registers.

Procedure for developing a questionnaire and interview guidelines:

- Analyse the project strategy

- Consider the projects results chains – do they cover all the relevant results hypotheses to be assessed in the impact assessment?

- Identify relevant assessment fields for the impact assessment along results chains

- Formulate results indicators and convert these into questions and answers, making sure it is easy to understand both the questions and the categories from which an answer is to be chosen.

- It may be necessary to translate the questionnaire into a local language.

- Pilot test your questionnaire before rolling it out to all the involved households.

Sample

In contrast to qualitative interviews, the sample size is fundamental for quantitative surveys. The size of the sample will depend on factors such as the baseline characteristics of the target population, the topics being studied, the resources available, and the degree of accuracy necessary. It has to be statistically significant. As a rule of thumb for household surveys, it is advisable to draw a sample of at least 40 to 50 households for each stratum (see below: stratified sample). In the case of very small numbers of sampling units, e.g. a very limited number of hospitals in the project area, it may be advisable to opt for qualitative approaches.

There are different types of sampling available. Depending on the survey context, one of the following sampling methods may be chosen:

- Full sample

Drawing a full sample represents the whole project. However, due to the large amount of time and effort needed in most cases, conducting interviews with all the sampling units present in the study area is only advisable for small, manageable numbers of sampling units. In most instances it is sufficient to draw smaller samples, since beyond a certain number, results are repetitive and the significance is not really affected by increasing same size.

- Random sample / Systematic sample

In a random sample, every individual unit in the population has an equal chance of being selected for the sample; selection occurs by chance, so a knowledge of the total population group is needed to ensure that everyone is represented. A totally random selection of households is difficult in practice, and the systematic sample is a common technique to draw near-random samples. For a systematic sample, every xth unit is selected (e.g. interviews are conducted in every third household on the interviewers’ way).

Random / systematic samples provide information about distributions within the whole population. For example, to gain information about the percentage of efficient stoves existing in a village, a random sample should be drawn.

- Stratified sample

Stratified samples are used to ensure that appropriate numbers of small subgroups are included in the sample. This could apply to surveys focusing on technologies that have not yet been widely disseminated, such as Solar Cookers. In this case ownership/non-ownership of a Solar Cooker might be a typical variable. Others might include socio-economic groups, districts, professional groups, etc. The percentage drawn from each stratum might be equal or variable, according to the needs of the survey. In the case of different percentages drawn for each stratum, data has to be weighted for analysis to represent the population correctly. For example, in a sample stratified by two household income groups, with 10% of all high-income households and 30% of all low-income households being interviewed, the data for high-income households has to be weighted by a factor of three. To develop a stratified sample, and to structure the sample accurately, requires a lot of reliable information about the total population group. This is a challenge in many cases, since available information is sometimes limited.

Example Kenya

In Kenya, impact assessments were conducted by selecting target group representatives in districts and villages using a set of selection criteria. Qualitative interviews using interview guidelines were conducted with selected local authorities. Selected women’s groups engaged in focus group discussions at village level, using a set of tools developed for Participatory Rapid Appraisal (PRA tools). These included elements such as trend analyses, activity lists, and influence matrices. Trained PRA experts were included in this exercise.

Finally structured interviews were conducted to produce a quantitative sample survey, administering questionnaires with the selected users (households, schools and restaurants) and producers. These interviews were carried out by and carefully chosen and trained enumerators, in most cases local students.

Data Processing

For the final components – data entry, analysis, and interpretation, it is recommended that a consultant, or team of consultants, is employed. These consultants should be involved in whole process of impact assessment, from advising on the crucial indicators through questionnaire development, and taking part in the data entry, analysis, and interpretation. Involvement of project staff, counterparts and local NGOs, students, etc. in various parts of the assessment (like preparation and data interpretation) is helpful and relevant for local knowledge transfer, capacity development, and for creation of ownership among all stakeholders. In Kenya, agricultural officers reported the enthusiasm of the targeted beneficiaries. One student who conducted the interviews in Kenya started his own stove business. Such examples show the secondary effect of these monitoring instruments, which might not have been anticipated.

A set of guiding questions for data analysis and interpretation was developed to support for the consultant in Kenya.

Additional information

- GTZ EnDev Guide Impact Assessment for Energising Development Projects, GTZ 2007

- Model List of Impacts, Observation Fields and Indicators for IA Kenya, GTZ HERA 2007

- Steps and Procedures - documented according to IA in Kenya. GTZ HERA 2007

- Selection Criteria for IA in Kenya, GTZ HERA 2007

Participatory Impact Assessment – an experiment?

In selected SADC countries, where the Programme for Biomass Energy Conservation, ProBEC, is implemented, impact assessment interviews were conducted by local stove artisans. In 2004 the stove promoters and producers from Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania and Kenya were invited to Malawi for a ProBEC Workshop about experience exchange on low-cost clay and ceramics.

Very interesting feedback was given by producers and promoters during the workshop about the results of the impact assessment. For many of them, it was the first time they had exchanged ideas with their customers, and thus they learnt firsthand about how the stoves were used, the way people had understood stove instructions, difficulties, problems and demands.

The stove producers, builders and promoters considered this so important that they passed a resolution asking for training in monitoring and impact assessment as part of their regular training programme. They realized that by asking the questions themselves, it would increase their awareness of the quality of their stoves, improve their marketing skills and thus their access to customers.

This approach to impact assessment requires high involvement by the producers, and creates business awareness. It should be considered as complementary or additional to an external, unbiased impact assessment by an external person. The results of an assessment by the manufacturers should not be considered neutral.

Additional information

Economic Evaluation on the basis of impact assessment data

The data from impact assessment can provide the starting point for an economic evaluation of the project, including a Cost-Benefit-Analysis (CBA) and a Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA). Analysing both the economic efficiency of the investments, and the benefits deriving from energy efficient stoves on a macro and micro level can be helpful for further lobbying, public relations and keeping control of the project.

A Cost Benefit Analysis of the Energy Advisory Project in Uganda demonstrated the economic value, for individual households as well as for the public sector, of using the Lorena Rocket stove. The same was shown in a Cost Benefit Analysis in ProBEC Malawi for social institutions like schools, hospitals and prisons.

GTZ Cost-Benefit Analysis –Tool

This tool is provided as a set of prepared excel sheets, where all data and information required for conduction an economic CBA needs to be entered into reserved cells. In addition GTZ HERA provides explanation on how to use the CBA tool.

Additional information

An evaluation of the costs and benefits of household energy and health interventions at global and regional levels as well as guidelines for conducting such cost-benefit analyses can be found at the WHO website:

http://www.who.int/indoorair/interventions/cost_effectiveness/en/index.html

WHO used the Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) as a tool for assessing the cost-effectiveness ratio of different interventions regarding indoor air pollution. This was applied to identify the intervention that provides the highest ‘value for money’. CEA results can thus help policy makers to choose the interventions and programmes that maximize health benefits for the available resources.

Three scenarios have been assessed: providing the population with access to cleaner fuels (kerosene, liquid petroleum gas); providing the population with access to improved stoves; providing part of the population with access to cleaner fuels and part of the population with improved stoves.

Experiences – pros and cons

Results Based Monitoring examines the assumptions the project has made in an empirical and systematic way. The result hypotheses are examined and may need to be adjusted after the monitoring has been completed. It helps to draw attention to wrong assumptions, and to avoid wrong planning and implementation directions. Beyond that, Results Based Monitoring provides a clear, visual presentation of the results that have been achieved.

Experience shows that the establishment of a solid Results Based Monitoring system is helpful for project management and evaluation, and creates a sense of ownership. The major purposes of Results Based Monitoring are thus to: steer interventions; make people accountable for the results; and contribute to internal learning and knowledge management.

However, there are challenges to this approach. It is important to realize that Results Based Monitoring is not an exercise that can be fully delegated to a consultant visiting the project every six months. As a management tool, Results Based Monitoring is primarily the responsibility of the project manager, and secondly, the joint responsibility of the whole project team. It needs to be included in the project planning, as well as into the budget.

Results Based Monitoring is based on a complex model, creating a lot of discussion among Monitoring and Evaluation experts. Capacity is required for its implementation, and everybody in charge of Results Based Monitoring in the project should be well trained and skilled in the subject.

In certain situations it makes sense to involve external consultants in Results Based Monitoring, particularly when an independent view is needed or required. In this case, a neutral person should carry out the impact assessment. This person should have expertise in qualitative and quantitative monitoring and evaluation methodologies, a minimum knowledge about cooking energy, experience with statistical and analytical tools, and should be given enough time. Enumerators are helpful for larger samples.

The interpretation of data is often too difficult for external experts alone. It is better for the analysed data to be interpreted with the project team, as this creates ownership among project stakeholders.

Finally, results and recommendations are ready to be presented to stakeholders – perhaps at certain occasions like a mid-term review, or at the end of the project. This is a very important part of the process. Time should be taken to prepare it properly, invite relevant stakeholders, and, where appropriate, to celebrate your results! Make sure to discuss and agree on follow-up of the recommendations.