Difference between revisions of "Urban Freight in Developing Cities"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

This form of distribution implies that a member of the farmer’s family travels to town, either on foot, by bicycle or a motorised vehicle and commercialises farm produce to local retailers or directly to the end consumers. Alternatively, a farmer sends his own pickup truck to town, the truck parks besides the pavement or at a road intersection and the produce is sold to passers-by straight from the truck.<br/> | This form of distribution implies that a member of the farmer’s family travels to town, either on foot, by bicycle or a motorised vehicle and commercialises farm produce to local retailers or directly to the end consumers. Alternatively, a farmer sends his own pickup truck to town, the truck parks besides the pavement or at a road intersection and the produce is sold to passers-by straight from the truck.<br/> | ||

| − | + | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:Non-motorised goods transport to the market in Vientiane, Laos..png|left|412px|alt=Non-motorised goods transport to the market in Vientiane, Laos..png]]<br/></p> | |

| − | [[File:Non-motorised goods transport to the market in Vientiane, Laos..png|left]]<br/> | ||

| − | |||

== '''Organised street markets'''<br/> == | == '''Organised street markets'''<br/> == | ||

| Line 59: | Line 57: | ||

Farmers bring their produce to a specialised morning market in the outskirts of a city. Sometimes they contract truck operators for the transportation. Shop owners and hawkers purchase produce and sell it in their shops or on local street markets, while restaurant owners purchase for in-house consumption. Wholesale trading with inventory: These establishments do not only trade perishables, but also food products from industrialised production, packaged and non-perishable. The producer can deal with few business partners and logistical destinations, the retailer may be able to purchase his complete demand for supplies from one business partner. The main purpose of a wholesale function is to bundle the regional demand into larger quantities, thus increasing commercial bargaining power towards producers.<br/> | Farmers bring their produce to a specialised morning market in the outskirts of a city. Sometimes they contract truck operators for the transportation. Shop owners and hawkers purchase produce and sell it in their shops or on local street markets, while restaurant owners purchase for in-house consumption. Wholesale trading with inventory: These establishments do not only trade perishables, but also food products from industrialised production, packaged and non-perishable. The producer can deal with few business partners and logistical destinations, the retailer may be able to purchase his complete demand for supplies from one business partner. The main purpose of a wholesale function is to bundle the regional demand into larger quantities, thus increasing commercial bargaining power towards producers.<br/> | ||

| − | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:Urban beverage distribution in Bangkok.png|left|379px|Urban beverage distribution in Bangkok]]<br/></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:Urban beverage distribution in Bangkok.png|left|379px|Urban beverage distribution in Bangkok|alt=Urban beverage distribution in Bangkok]]<br/></p> |

== '''Delivery of building materials''' == | == '''Delivery of building materials''' == | ||

| Line 67: | Line 65: | ||

In a typical developing country situation, a large portion of the goods volume is usually moved through “own account” vehicles. This means that vehicles are owned and deployed either by the vendor or purchaser of the merchandise. Own account operations tend to be logistically less efficient than third account hauliers. This is due to generally smaller vehicle sizes, lower load factors and the lack of return cargo. The latter implies that the vehicle is only loaded with cargo one-way and returning totally empty from its delivery trip. The development of a competitive and professional dedicated freight company structure should be one of the policy objectives for metropolitan authorities.<br/> | In a typical developing country situation, a large portion of the goods volume is usually moved through “own account” vehicles. This means that vehicles are owned and deployed either by the vendor or purchaser of the merchandise. Own account operations tend to be logistically less efficient than third account hauliers. This is due to generally smaller vehicle sizes, lower load factors and the lack of return cargo. The latter implies that the vehicle is only loaded with cargo one-way and returning totally empty from its delivery trip. The development of a competitive and professional dedicated freight company structure should be one of the policy objectives for metropolitan authorities.<br/> | ||

| − | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:Own account vehicle freight transport in Johannesburg.png|left|421px]]<br/></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:Own account vehicle freight transport in Johannesburg.png|left|421px|alt=Own account vehicle freight transport in Johannesburg.png]]<br/></p> |

== '''Proprietary logistics centres''' == | == '''Proprietary logistics centres''' == | ||

Proprietary logistics hubs are owned and operated by a single company for their specific business only. Parcel services have professionalized this concept. In general, they run one or several distribution centres on the outskirts of a city or close to a freeway exit. Proprietary logistics hubs are also operated by retail chains, as for instance grocery discounters. The purpose of these distribution centres is to break the transport run into the long-haul and the delivery portion. From all incoming long-distance truckloads, destination specific, route specific or area specific loads are consolidated.<br/> | Proprietary logistics hubs are owned and operated by a single company for their specific business only. Parcel services have professionalized this concept. In general, they run one or several distribution centres on the outskirts of a city or close to a freeway exit. Proprietary logistics hubs are also operated by retail chains, as for instance grocery discounters. The purpose of these distribution centres is to break the transport run into the long-haul and the delivery portion. From all incoming long-distance truckloads, destination specific, route specific or area specific loads are consolidated.<br/> | ||

| − | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:City served through a proprietary consolidation hub.png|left|600px]]<br/></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:City served through a proprietary consolidation hub.png|left|600px|alt=City served through a proprietary consolidation hub.png]]<br/></p> |

= '''Conclusions'''<br/> = | = '''Conclusions'''<br/> = | ||

| Line 86: | Line 84: | ||

Bernhard O. Herzog 2010, ''Urban Freight in developing cities''<br/> | Bernhard O. Herzog 2010, ''Urban Freight in developing cities''<br/> | ||

| + | [[Category:Mobility]] | ||

[[Category:Transport]] | [[Category:Transport]] | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 01:46, 10 April 2013

Relevance of freight in urban transportation

The economic development of urban agglomerations depends heavily on a reliable and friction- free supply of goods and materials. At the same time, freight transportation in urban centres contributes considerably to air pollution, noise emission and traffic congestion. On the level of a typical metropolitan area in a developing country, on average 40–50 % of commercial vehicle freight volume is incoming, 20–25 % is outgoing, and the remaining 25–40 % are intra-metropolitan runs. However, typical good flows vary among different functional city areas. Large urban agglomerations include industrial zones and therefore mostly act more as origin for goods transport than as destination. In contrast, city centres, be it the downtown centre or a suburban commercial centre, are usually strong net goods consumers. This implies that more goods are received than dispatched in these precincts. Delivery of sometimes small shipments to the various retail establishments is the main topic here.

Urban freight transportation and urban development are interdependent: A strangulation of the flow of goods in and out of a metropolis would certainly increase the retail price levels, impair the development of the urban centre itself, slow down economic activity and drain the financial resources from the municipal budget. On the other hand, only a stringent and long term metropolitan policy on urban transport can ensure an efficient and sustainable supply structure.

Development of new models for low and middle income countries

Concepts which have proved useful in a western economy do not necessarily work in a developing country environment. Some Asian conurbations present a much higher pressure for action and may therefore be a fertile ground for the implementation of innovative urban logistics concepts, if approached in the right manner. The measures so far implemented in low- and middle income countries may be less sophisticated, but generally it can be said that there is a high degree of public awareness and a sense of urgency concerning urban logistics problems. Many initiatives are underway in prospering cities of Asia and Latin America, aimed at alleviating the negative effects of urban freight transport while securing a friction-free supply of goods into the cities. In many instances, these programs focus on the eco-efficiency of the national vehicle fleet and on the performance of the road infrastructure. Increasingly, traffic management measures can be observed, in some cases accompanied by the provision of truck parking space or of urban logistics centres.

Problems induced by urban freight traffic

Roadspace occupation

Roadspace is scarce in just about any urban agglomeration. Especially if larger than necessary vehicles are used, if unnecessary long distances are travelled in urban regions, and if the off-loading process is organised in an inefficient way.

Green House Gas (GHG) and particle matter (PM) emissions

GHG emissions and local air pollution are serious consequences. Emissions of GHG such as carbon dioxide (CO2) can be minimised by using clean vehicle technologies and through an optimisation of the logistics system. Especially with diesel-driven vehicles, the particle-matter (PM) emissions are the main problem. They are responsible for major health hazards to the urban populations, including asthma attacks and other forms of respiratory illness. In addition, air pollution can cause damage to historic buildings and other cultural resources.

Noise emissions

Traffic noise has severe impacts on health and overall quality of life. It may lead to stress and increased blood pressure. In the medium and long term, the reduction of traffic noise in the vicinity of residential areas is likely to become a focus in all regions.

Impairment of road safety

Wherever heavy vehicles mix with passenger vehicles, bicycles or pedestrians, the risk of accidents and serious personal damage is increased. In very few situations is it possible to segregate the different vehicle categories. Only professional traffic engineering, good traffic management and an efficient organisation of the logistics sector can alleviate this problem.

Damage to road infrastructure

Heavy freight trucks increase the potential for damage to the infrastructure. Especially overloading and a poor technical condition of the vehicle fleet contribute more than necessarily to road infrastructure wear and tear and reduce their service life.

Congestion/delays

Depending on the way goods traffic is organised, it may even have negative effects on traffic flow way beyond its actual share of the traffic volume. Especially in situations where no efficient parking and loading regime has been established, goods distribution sometimes becomes the main cause of traffic congestion.

Negative impacts on economic competitiveness and urban development

A functioning city goods distribution and transport system is a major precondition for sustained economic development and thus, for poverty reduction. If a reliable and efficient supply of goods to inner city retail outlets cannot be established and ensured, commercial activity might shift to more easily accessible locations.

A review of proven city logistics concepts

Prior to discussing possible measure to improve the efficiency of city logistics systems for developing cities, it is helpful to quickly review the past development of the sector and illustrate some logistical concepts which have proven to be economically viable and sustainable. Usually they have developed organically out of private sector initiative.

Farmer direct selling

This form of distribution implies that a member of the farmer’s family travels to town, either on foot, by bicycle or a motorised vehicle and commercialises farm produce to local retailers or directly to the end consumers. Alternatively, a farmer sends his own pickup truck to town, the truck parks besides the pavement or at a road intersection and the produce is sold to passers-by straight from the truck.

Organised street markets

Street markets are a common appearance in most cities, and may take place daily, weekly or biweekly. Sometimes these markets are specialised, e.g. for fruit, vegetables, seafood. From a logistical perspective, this means that farmers send their produce to an organised market place in town and sell it direct to the public.

Wholesale and morning markets for Perishables

Farmers bring their produce to a specialised morning market in the outskirts of a city. Sometimes they contract truck operators for the transportation. Shop owners and hawkers purchase produce and sell it in their shops or on local street markets, while restaurant owners purchase for in-house consumption. Wholesale trading with inventory: These establishments do not only trade perishables, but also food products from industrialised production, packaged and non-perishable. The producer can deal with few business partners and logistical destinations, the retailer may be able to purchase his complete demand for supplies from one business partner. The main purpose of a wholesale function is to bundle the regional demand into larger quantities, thus increasing commercial bargaining power towards producers.

Delivery of building materials

In rapidly growing urban agglomerations, up to 30 % of the transported goods tonnage is building materials and construction equipment. In congested metropolitan areas and commercial inner city districts, the logistical bottleneck is the off-loading operation at the construction site. Sometimes, no off road parking is available at all, space is always scarce and if not organised correctly, the off-loading operation produces long vehicle queues.

Development of the “third account” transport sector

In a typical developing country situation, a large portion of the goods volume is usually moved through “own account” vehicles. This means that vehicles are owned and deployed either by the vendor or purchaser of the merchandise. Own account operations tend to be logistically less efficient than third account hauliers. This is due to generally smaller vehicle sizes, lower load factors and the lack of return cargo. The latter implies that the vehicle is only loaded with cargo one-way and returning totally empty from its delivery trip. The development of a competitive and professional dedicated freight company structure should be one of the policy objectives for metropolitan authorities.

Proprietary logistics centres

Proprietary logistics hubs are owned and operated by a single company for their specific business only. Parcel services have professionalized this concept. In general, they run one or several distribution centres on the outskirts of a city or close to a freeway exit. Proprietary logistics hubs are also operated by retail chains, as for instance grocery discounters. The purpose of these distribution centres is to break the transport run into the long-haul and the delivery portion. From all incoming long-distance truckloads, destination specific, route specific or area specific loads are consolidated.

Conclusions

Analysing the prevalent trends in demographics, urban structures and industry development it becomes obvious, that many of the developments, such as urban population growth, increased motorisation or shift towards industrialised food production have negative effects on the traffic and environmental situation in cities, or at least represent major challenges to local authorities.

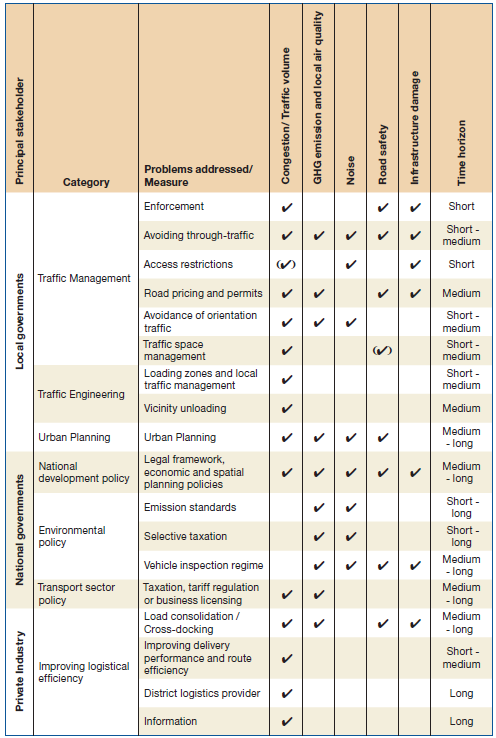

The urban freight policy will have to find the right answers in order to cope successfully with the challenges of the future. Relevant measures are presented in the following figure.

Whatever the approach may be: cities and metropolitan areas have to develop and implement a viable strategy for the optimisation of the urban freight system. The environmental sustainability, economic development and overall quality of urban living depend on it.

Further Information

Further and more detailed information can be found on the homepage of the Sustainable Urban Transport Project. The Sustainable Urban Transport Project aims to help developing world cities achieve their sustainable transport goals, through the dissemination of information about international experience, policy advice, training and capacity building.

References

Bernhard O. Herzog 2010, Urban Freight in developing cities