Difference between revisions of "Financing energy access"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) m |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | = | + | = Overview<br/> = |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | According to the IEA “Energy for all Case”, providing electricity and clean cooking for all would require $786 billion in cumulative investment in the period from 2017 to 2030, equal to 3.4% of the total energy sector investment over the period. This would mean an additional $31 billion per year on top of the $25 billion per year projected under the “New Policies Scenario”, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for the largest share of investment, followed by developing Asia. | + | According to the IEA “Energy for all Case”, providing electricity and clean cooking for all would require $786 billion in cumulative investment in the period from 2017 to 2030, equal to 3.4% of the total energy sector investment over the period. This would mean an additional $31 billion per year on top of the $25 billion per year projected under the “New Policies Scenario”, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for the largest share of investment, followed by developing Asia.<ref name="IEA, World Energy Outlook 2017 Special Report, Energy Access Outlook">IEA, World Energy Outlook 2017 Special Report, Energy Access Outlook</ref> |

| + | <p style="text-align: center">[[File:Cumulative investment in modern energy access, 2017-2030 (IEA).png|center|500px|alt=Cumulative investment in modern energy access, 2017-2030 (IEA).png]]</p><p style="text-align: center">Cumulative investment in modern energy access, 2017-2030 (IEA)</p> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| − | + | With the '''increased role of decentralized solutions for electrification''', the target of this investment is continuously shifting in that direction, with mini-grids expected to get the largest share with 48%, followed by grid with 29% and off-grid with 23%. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | With the increased role of decentralized solutions for electrification, the target of this investment is continuously shifting in that direction, with mini-grids expected to get the largest share with 48%, followed by grid with 29% and off-grid with 23%. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[File:Additional average annual investment related to electricity access in the Energy for All Case relative to the New Policies Scenario, 2017-2030 (IEA).png|center|500px|alt=Additional average annual investment related to electricity access in the Energy for All Case relative to the New Policies Scenario, 2017-2030 (IEA).png]] | ||

| + | <p style="text-align: center">Additional average annual investment related to electricity access in the Energy for All Case relative to the New Policies Scenario, 2017-2030 (IEA)</p> | ||

<br/><br/> | <br/><br/> | ||

| − | = Electrification models | + | = Electrification models = |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | Nearly all developed countries have reached 100% electrification by grid-extension, which was financed by cross-subsidizing the costly rural connections with the profitable urban connections, resulting in an overall profit for the utility.<span style="font-size: 0.85em | + | Nearly all developed countries have reached 100% electrification by '''grid-extension''', which was '''financed by cross-subsidizing''' the costly rural connections with the profitable urban connections, resulting in an overall profit for the utility.<span style="font-size: 0.85em"> </span> |

| − | In some developing countries this electrification model has proven suitable. In India for example, 500 million people, nearly half the country’s population, gained energy access between 2000 and 2016. This was heralded as “one of the largest electrification success stories in history”. More than 99% of this segment gained energy access through grid extensions. This account demonstrates that high levels of centralized energy access are indeed achievable within the developing world. | + | In some developing countries this electrification model has proven suitable. In '''India''' for example, 500 million people, nearly half the country’s population, gained energy access between 2000 and 2016. This was heralded as “one of the largest electrification success stories in history”. More than'''99% of this segment gained energy access through grid extensions'''. This account demonstrates that high levels of centralized energy access are indeed achievable within the developing world. |

| − | However, India is rather the exception than the rule, as the situation in most developing countries, especially sub-Saharan Africa, is very different because nearly all state owned utilities are running their business with vast annual deficits. Where a company is running at a loss it is difficult to make investments in new grid-connections, especially for the poor that will have a low demand and low capacity to pay. <span style="font-size: 0.85em | + | However, India is rather the exception than the rule, as the situation in most developing countries, especially '''sub-Saharan Africa''', is very different because nearly all '''state owned utilities are running their business with vast annual deficits'''. Where a company is running at a loss it is difficult to make investments in new grid-connections, especially for the poor that will have a low demand and low capacity to pay. <span style="font-size: 0.85em"> </span> |

| − | Furthermore, assumptions that are usually taken for granted in developed countries, such as stable regimes and clearly defined tax laws, are not necessarily present in many developing countries that need to increase the pace of electrification. Efforts are often met with weak regulation and heavy corruption, all of which creates a much higher level of risk in investments. | + | Furthermore, assumptions that are usually taken for granted in developed countries, such as '''stable regimes''' and '''clearly defined tax laws''', are not necessarily present in many developing countries that need to increase the pace of electrification. Efforts are often met with '''weak regulation''' and '''heavy corruption''', all of which creates a much higher level of risk in investments. |

| − | + | <br/> | |

= Funding methods = | = Funding methods = | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | Over the previous years, we have observed substantial growth in private sector investment. Creative new business models are increasing private sector investment in projects which range from large-scale infrastructure to targeted micro schemes. | + | Over the previous years, we have observed substantial growth in'''private sector investment.''' Creative new business models are increasing private sector investment in projects which range from large-scale infrastructure to targeted micro schemes.<ref name="UNCTAD, The role of development banks in promoting growth and sustainable development in the South, 2016">UNCTAD, The role of development banks in promoting growth and sustainable development in the South, 201</ref> Despite these positive trends, electricity infrastructure assets, whether on-grid or off-grid, typically require a relatively large upfront investment that is not likely to generate a return on investment in the initial phases of the project, especially where large sections of the population have limited payment abilities. As a result, we find that many projects that target energy access to the poor un-electrified population face an '''additional funding challenge''', especially in the initial phases of the project were the income generated is minimal. This is why many projects that aim to close the energy access gap are not commercially viable: in these cases, innovative partnerships and business models will have to be developed to secure the upfront costs and the long-term sustainability of the projects.One example of this type of funding gap can be found in a case study done in '''Bihar, India''', where the up-front cost for a hybrid micro-grid would be about $44,000, but analysis showed that a $27,000 subsidy was needed before potential investors would consider coming on board.Diverse and innovative funding methods and partnerships are crucial to meet the increased financing needs to ensure universal access to energy by 2030. '''Loans, grants''' and '''subsidies''' will play an important role in getting projects off the ground, while '''foreign investment''' will be fundamental in taking these projects to scale. Many different players and stakeholders will have to be involved in the process, a process that is often highly complex. '''Both centralized and decentralized electrification are essential''' as they will serve different populations. They must be coordinated so they complement each other rather than unnecessarily compete. Electrification through grid-connection will require a specific approach and an appropriate funding mechanism, while electrification through off-grid and stand alone systems will need a different approach with coordinated funding mechanisms. |

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | {{Go to Top}} | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| − | + | = Funding sources = | |

| − | + | <br/>Currently, funding to the energy sector comes from a number of different sources, and a rough estimate from the IEA is as follows: '''developing countries own budgets 37%''','''multilateral organisations 33%''', '''private investors 18%''' and '''bilateral aid 12%'''. [[File:World energy access investment by type and source, 2013 (IEA).png|center|500px|alt=World energy access investment by type and source, 2013 (IEA).png]] | |

| + | <p style="text-align: center">World energy access investment by type and source, 2013 (IEA)</p> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| − | + | == Own sources == | |

| − | + | <br/>Most countries have a central '''Ministry''' directly responsible for electricity supply. They may also set up agencies inside the Ministry itself, in charge of individual elements such as '''rural electrification''' or '''financial planning'''. In India, for example, the Ministry of Power is the overarching body across the sector. Within it, the Rural Electrification Corporation (REC) has the key objective to finance and promote energy access projects across the country. The governing body in Indonesia also has a similar structure, with a national utility PLN and a Ministry agency (DGEEU) handling the rural electrification programs. The budget comes from a specially allocated fund known as the Dana Alokasi Khusus (DAK). It is a highly useful policy tool designed by the government to make monetary transfers to the regional and district level governments, earmarked for energy access as well as other initiatives.<br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Most countries have a central Ministry directly responsible for electricity supply. They may also set up agencies inside the Ministry itself, in charge of individual elements such as rural electrification or financial planning. In India, for example, the Ministry of Power is the overarching body across the sector. Within it, the Rural Electrification Corporation (REC) has the key objective to finance and promote energy access projects across the country. The governing body in Indonesia also has a similar structure, with a national utility PLN and a Ministry agency (DGEEU) handling the rural electrification programs. The budget comes from a specially allocated fund known as the Dana Alokasi Khusus (DAK). It is a highly useful policy tool designed by the government to make monetary transfers to the regional and district level governments, earmarked for energy access as well as other initiatives. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Multilateral Development Banks <u>(National, regional and international)</u> == | == Multilateral Development Banks <u>(National, regional and international)</u> == | ||

| − | + | <br/>Multilateral aid is delivered through international institutions such as the various agencies of the '''World Bank''' and '''the United Nations''', and has a '''broad mandate to finance development and structural reform'''. Their priority is predominantly '''socioeconomic '''rather than purely commercial, which explains why they have a key role to play in filling the gaps left by governments and private companies in relation to access to energy. This is particularly true for large-scale energy projects with long maturation periods which require long-term, risky financing that commercial banks are reluctant to provide. Furthermore, many such large-scale energy projects have greater social rather than economic returns, and are therefore an obvious target for multilateral aid.In addition to addressing long-term funding needs, Development Banks can also play an important role in shaping and '''steering the national and regional financial development system''' by creating and providing financing instruments that better spread the financial risk among creditors and borrowers and over time. Furthermore, as established institutional players, development banks can influence and support a proactive '''national and regional development strategy''' and help leverage resources by attracting other lenders and providing guarantees.<br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | Multilateral aid is delivered through international institutions such as the various agencies of the World Bank and the United Nations, and has a broad mandate to finance development and structural reform. Their priority is predominantly socioeconomic rather than purely commercial, which explains why they have a key role to play in filling the gaps left by governments and private companies in relation to access to energy. This is particularly true for large-scale energy projects with long maturation periods which require long-term, risky financing that commercial banks are reluctant to provide. Furthermore, many such large-scale energy projects have greater social rather than economic returns, and are therefore an obvious target for multilateral aid. | ||

| − | |||

| − | In addition to addressing long-term funding needs, Development Banks can also play an important role in shaping and steering the national and regional financial development system by creating and providing financing instruments that better spread the financial risk among creditors and borrowers and over time. Furthermore, as established institutional players, development banks can influence and support a proactive national and regional development strategy and help leverage resources by attracting other lenders and providing guarantees. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Private Investors == | |

| − | + | <br/>There are many '''investment firms''' dedicated to development initiatives, including energy access. '''Private equity funds''' are also numerous and active. One example is Energy Access Ventures (EAV), which promotes low-cost and low-carbon solutions to address the lack of electrification across Sub-Saharan Africa. It specifically caters to geographical areas that cannot gain access to traditional methods of finance. '''Multinational corporations''' (MNCs) also play a significant role by either entering the industry themselves, usually by investing in local companies already present in the space, or by donating to international organizations tackling the issue. Key examples include Samsung, Schneider Electric, Caterpillar Incorporated, Ikea, Google, Microsoft and Tesla.<br/> | |

== Bilateral aid == | == Bilateral aid == | ||

| − | + | <br/>Bilateral aid is given by one government directly to the government of a developing country to '''support economic, environmental, social, and political development'''. Although the SDG target 17.2 reiterates developed countries’ longstanding commitment to provide 0.7 % of their gross national income (GNI) in Official Development Assistance (ODA) to developing countries, only a handful of countries, mainly from Scandinavia and northern Europe, are meeting this target. | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | Bilateral aid is given by one government directly to the government of a developing country to support economic, environmental, social, and political development. Although the SDG target 17.2 reiterates developed countries’ longstanding commitment to provide 0.7 % of their gross national income (GNI) in Official Development Assistance (ODA) to developing countries, only a handful of countries, mainly from Scandinavia and northern Europe, are meeting this target. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Pilot projects == | == Pilot projects == | ||

| − | + | <br/>Aid effectiveness has been a hot topic in previous years. Without entering into the debate, it is clear that '''development aid '''has made it possible to fund energy '''pilot projects in rural communities''' in some of the least developed countries, which would have otherwise been impossible. While these pilot projects have only, at most, provided low levels of energy access to very few, they have served as the '''test and trial ground '''upon which some solid business cases have been built and which the private sector now is considering to scale up.<br/>Recent political developments and continued economic stress in major donor economies, combined with the aid effectiveness debate, are causing some donors to rethink their development aid commitments, including possibly abandoning the commitment to provide 0.7 % GNI in ODA and reducing contributions to multilateral bodies such as the World Bank. | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | Aid effectiveness has been a hot topic in previous years. Without entering into the debate, it is clear that development aid has made it possible to fund energy pilot projects in rural communities in some of the least developed countries, which would have otherwise been impossible. While these pilot projects have only, at most, provided low levels of energy access to very few, they have served as the test and trial ground upon which some solid business cases have been built and which the private sector now is considering to scale up. Recent political developments and continued economic stress in major donor economies, combined with the aid effectiveness debate, are causing some donors to rethink their development aid commitments, including possibly abandoning the commitment to provide 0.7 % GNI in ODA and reducing contributions to multilateral bodies such as the World Bank. | + | {{Go to Top}} |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

= Potential Solutions = | = Potential Solutions = | ||

| − | + | <br/>We may perceive that a '''new development finance paradigm is emerging''', one in which traditional development aid is replaced by a blend of public and private finance that includes a wider range of investors like development finance institutions, private equity managers, impact investors and institutional investors alongside NGOs and philanthropists. The result is an '''interlaced web of public and private interests and motivations''', which has exhibited a remarkable ability to raise large amounts of development finance. In recent years we have observed a growing trend of such partnerships including the European Sustainable Development Fund, Africa-EU Energy Partnership (AEEP), ElectriFi, Africa Power Vision, Energies pour l’Afrique etc, and a large majority of them focus on the '''promotion of renewable energy''' and address the electricity sector. Furthermore, there has been a proliferation of infrastructure- and energy-specific development funding as well as the creation of '''climate and green financing '''facilities, at the bilateral, regional and multilateral level. Such initiatives are often linked to climate-change policy or sustainable development and may or may not target energy infrastructure and/or access. | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | We may perceive that a new development finance paradigm is emerging, one in which traditional development aid is replaced by a blend of public and private finance that includes a wider range of investors like development finance institutions, private equity managers, impact investors and institutional investors alongside NGOs and philanthropists. The result is an interlaced web of public and private interests and motivations, which has exhibited a remarkable ability to raise large amounts of development finance. In recent years we have observed a growing trend of such partnerships including the European Sustainable Development Fund, Africa-EU Energy Partnership (AEEP), ElectriFi, Africa Power Vision, Energies pour l’Afrique etc, and a large majority of them focus on the promotion of renewable energy and address the electricity sector. Furthermore, there has been a proliferation of infrastructure- and energy-specific development funding as well as the creation of climate and green financing facilities, at the bilateral, regional and multilateral level. Such initiatives are often linked to climate-change policy or sustainable development and may or may not target energy infrastructure and/or access. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Impact Investing == | == Impact Investing == | ||

| − | + | <br/>The field of impact investing, in particular, has made significant strides and continues to gain momentum in this domain. '''North American '''and '''European institutions''' have played a key role in the development of the industry and we are starting to see its rise in '''Asia'''. For the most part, these are private firms with strong links to the public sector, whose distinguishing factor is their desire to achieve something of intrinsic value while generating a profit. '''Financial and social/environmental impacts are equally important''' factors that contribute to the decision-making regarding companies/projects to invest in. These projects cover a range of fields, such as '''education''', '''healthcare '''and '''sustainability''', with renewable energy playing an increasingly important role. Most other organizations are unwilling or do not have the capacity to take on long-term investments of about 25 years, which is what the traditional grid sector has generally required. However, impact investment firms might finally provide substantial help to finding solutions to bridging the funding gap in financing energy access. | |

| − | |||

| − | The field of impact investing, in particular, has made significant strides and continues to gain momentum in this domain. North American and European institutions have played a key role in the development of the industry and we are starting to see its rise in Asia. For the most part, these are private firms with strong links to the public sector, whose distinguishing factor is their desire to achieve something of intrinsic value while generating a profit. Financial and social/environmental impacts are equally important factors that contribute to the decision-making regarding companies/projects to invest in. These projects cover a range of fields, such as education, healthcare and sustainability, with renewable energy playing an increasingly important role. Most other organizations are unwilling or do not have the capacity to take on long-term investments of about 25 years, which is what the traditional grid sector has generally required. However, impact investment firms might finally provide substantial help to finding solutions to bridging the funding gap in financing energy access | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | + | The United Nations Foundation understands the power of impact investing and created a directory of impact investing opportunities in 2013. Known as the “'''Energy Access Practitioner Network'''”, the report provides a comprehensive look at investment opportunities around the world in order to achieve universal energy access by 2030. The network comprises of more than 1,500 organizations specifically geared towards tailoring financial solutions for social enterprises in the sector. They are clear in their thinking that one size does not fit all, thus considering off-grid solutions, accounting for local conditions as well as customers’ payment capacity.For example, Schneider Electric entered the field in 2009 due to its strong belief that “impact investing will be part of the solution to close the energy gap in the coming years”. The Schneider Electric Energy Access (SEEA) fund supports small and medium businesses with innovative solutions for providing energy access to the 1.06 billion people who still lack it; Schneider also participates in the EAV mentioned above. |

== Political and regulatory framework == | == Political and regulatory framework == | ||

| − | + | <br/>There are additional matters that need to be prioritized in order to concretely bridge the funding gap, not only from the finance side but also from the policy viewpoint. The current situation needs to be thoroughly assessed and modified based on innovative mechanisms that have quickly come into play over recent years. “'''Pay-as-you-go” models '''and '''microfinance institutions''' have achieved considerable results but need to be supplemented through other initiatives. While high/middle income countries are more likely to raise private funds, public organizations are still the best options for low income countries and must be given their due credit. '''Regulatory agencies''' are key in tracking their progress and ensuring that resources are being effectively allocated to financing mechanisms. | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | There are additional matters that need to be prioritized in order to concretely bridge the funding gap, not only from the finance side but also from the policy viewpoint. The current situation needs to be thoroughly assessed and modified based on innovative mechanisms that have quickly come into play over recent years. | + | {{Go to Top}} |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

= Conclusion = | = Conclusion = | ||

| − | + | <br/>Although the prospect of universal energy access may seem daunting, it is indeed achievable given the right methodologies in both finance and technology. The amount of '''funding needed is much higher than what is currently available'''. Equally as important to funding quantity, however, are the '''financial procedures and structures '''that need to be implemented to attract foreign investment in low and medium access countries. Without that, these countries will have to rely more heavily on traditional loans, grants and subsidies which may also yield results in time. Innovation in the financial sector must also play a key role in years to come as methods that have worked for traditional, grid-based systems may no longer be valid in the developing world. In conclusion, achieving the SDG7 hinges on greater and different methods of funding the energy gap. | |

| − | |||

| − | Although the prospect of universal energy access may seem daunting, it is indeed achievable given the right methodologies in both finance and technology. The amount of funding needed is much higher than what is currently available. Equally as important to funding quantity, however, are the financial procedures and structures that need to be implemented to attract foreign investment in low and medium access countries. Without that, these countries will have to rely more heavily on traditional loans, grants and subsidies which may also yield results in time. Innovation in the financial sector must also play a key role in years to come as methods that have worked for traditional, grid-based systems may no longer be valid in the developing world. In conclusion, achieving the SDG7 hinges on greater and different methods of funding the energy gap. | ||

| − | |||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| + | {{Go to Top}} | ||

| + | <br/><br/> | ||

= References = | = References = | ||

| − | <br/> | + | <references /><br/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Countries Portal, Energypedia. | + | *IEA, [https://webstore.iea.org/weo-2017-special-report-energy-access-outlook World Energy Outlook 2017 Special Report, Energy Access Outlook], 2017 |

| + | *World Bank, [http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/energy/publication/global-tracking-framework-2017 Global Tracking Framework - Progress Toward Sustainable Energy], 2017 | ||

| + | *UNCTAD, [http://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=1699 The role of development banks in promoting growth and sustainable development in the South], 2016 | ||

| + | *OECD, [https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/Towards-a-Framework-for-the-Governance-of-Infrastructure.pdf Towards a Framework for the Governance of Infrastructure], Public Governance and Territorial Development Directorate, 2015 | ||

| + | *Florence School of Regulation, [http://fsr.eui.eu/training/energy/regulation-universal-access-energy/ Regulation for Universal Access to Energy online course] | ||

| + | *IIED, [http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/16621IIED.pdf Unlocking climate finance for decentralized energy access], 2016 | ||

| + | *India historic success for electricity access, future connections will be decentralized: IEA. Power for All, 2017. | ||

| + | *[[:Portal:Countries|Countries Portal, Energypedia.]] | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

= Further Information<br/> = | = Further Information<br/> = | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{EnergyAccessPortal}} | ||

*[[Portal:Energy Access|Portal:Energy Access]] | *[[Portal:Energy Access|Portal:Energy Access]] | ||

| Line 175: | Line 117: | ||

*[[Off-grid Energy Companies and Financial Institutions - Need and Options for Collaboration|Off-grid Energy Companies and Financial Institutions - Need and Options for Collaboration]] | *[[Off-grid Energy Companies and Financial Institutions - Need and Options for Collaboration|Off-grid Energy Companies and Financial Institutions - Need and Options for Collaboration]] | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | '''Written by: [http://fsr.eui.eu/people/pia-lovengreen-alessi/ Pia Lovengreen Alessi], [http://fsr.eui.eu/universal-access-energy/ Florence School of Regulation] | + | {{Go to Top}}<br/>{{Access_Footer}}<br/>'''Written by: [http://fsr.eui.eu/people/pia-lovengreen-alessi/ Pia Lovengreen Alessi], [http://fsr.eui.eu/universal-access-energy/ Florence School of Regulation] Advisor and [http://www.wame2015.org/ WAME] project coordinator and Aakriti Samaiyar'''.<br/> |

| + | [[Category:Financing_and_Funding]] | ||

[[Category:Energy_Access]] | [[Category:Energy_Access]] | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 10:08, 1 May 2018

Overview

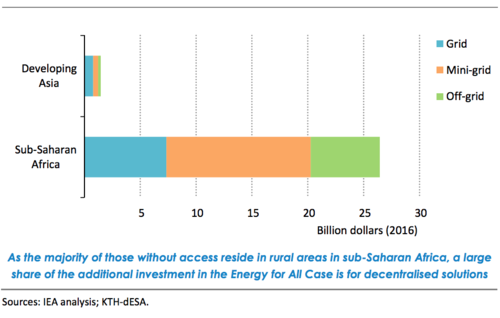

According to the IEA “Energy for all Case”, providing electricity and clean cooking for all would require $786 billion in cumulative investment in the period from 2017 to 2030, equal to 3.4% of the total energy sector investment over the period. This would mean an additional $31 billion per year on top of the $25 billion per year projected under the “New Policies Scenario”, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for the largest share of investment, followed by developing Asia.[1]

Cumulative investment in modern energy access, 2017-2030 (IEA)

With the increased role of decentralized solutions for electrification, the target of this investment is continuously shifting in that direction, with mini-grids expected to get the largest share with 48%, followed by grid with 29% and off-grid with 23%.

Additional average annual investment related to electricity access in the Energy for All Case relative to the New Policies Scenario, 2017-2030 (IEA)

Electrification models

Nearly all developed countries have reached 100% electrification by grid-extension, which was financed by cross-subsidizing the costly rural connections with the profitable urban connections, resulting in an overall profit for the utility.

In some developing countries this electrification model has proven suitable. In India for example, 500 million people, nearly half the country’s population, gained energy access between 2000 and 2016. This was heralded as “one of the largest electrification success stories in history”. More than99% of this segment gained energy access through grid extensions. This account demonstrates that high levels of centralized energy access are indeed achievable within the developing world.

However, India is rather the exception than the rule, as the situation in most developing countries, especially sub-Saharan Africa, is very different because nearly all state owned utilities are running their business with vast annual deficits. Where a company is running at a loss it is difficult to make investments in new grid-connections, especially for the poor that will have a low demand and low capacity to pay.

Furthermore, assumptions that are usually taken for granted in developed countries, such as stable regimes and clearly defined tax laws, are not necessarily present in many developing countries that need to increase the pace of electrification. Efforts are often met with weak regulation and heavy corruption, all of which creates a much higher level of risk in investments.

Funding methods

Over the previous years, we have observed substantial growth inprivate sector investment. Creative new business models are increasing private sector investment in projects which range from large-scale infrastructure to targeted micro schemes.[2] Despite these positive trends, electricity infrastructure assets, whether on-grid or off-grid, typically require a relatively large upfront investment that is not likely to generate a return on investment in the initial phases of the project, especially where large sections of the population have limited payment abilities. As a result, we find that many projects that target energy access to the poor un-electrified population face an additional funding challenge, especially in the initial phases of the project were the income generated is minimal. This is why many projects that aim to close the energy access gap are not commercially viable: in these cases, innovative partnerships and business models will have to be developed to secure the upfront costs and the long-term sustainability of the projects.One example of this type of funding gap can be found in a case study done in Bihar, India, where the up-front cost for a hybrid micro-grid would be about $44,000, but analysis showed that a $27,000 subsidy was needed before potential investors would consider coming on board.Diverse and innovative funding methods and partnerships are crucial to meet the increased financing needs to ensure universal access to energy by 2030. Loans, grants and subsidies will play an important role in getting projects off the ground, while foreign investment will be fundamental in taking these projects to scale. Many different players and stakeholders will have to be involved in the process, a process that is often highly complex. Both centralized and decentralized electrification are essential as they will serve different populations. They must be coordinated so they complement each other rather than unnecessarily compete. Electrification through grid-connection will require a specific approach and an appropriate funding mechanism, while electrification through off-grid and stand alone systems will need a different approach with coordinated funding mechanisms.

►Go to Top

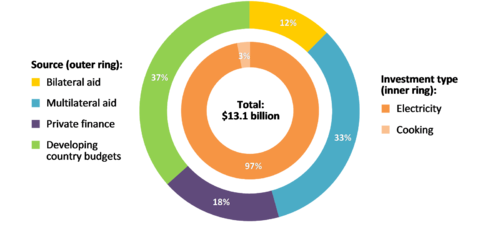

Funding sources

Currently, funding to the energy sector comes from a number of different sources, and a rough estimate from the IEA is as follows: developing countries own budgets 37%,multilateral organisations 33%, private investors 18% and bilateral aid 12%.

World energy access investment by type and source, 2013 (IEA)

Own sources

Most countries have a central Ministry directly responsible for electricity supply. They may also set up agencies inside the Ministry itself, in charge of individual elements such as rural electrification or financial planning. In India, for example, the Ministry of Power is the overarching body across the sector. Within it, the Rural Electrification Corporation (REC) has the key objective to finance and promote energy access projects across the country. The governing body in Indonesia also has a similar structure, with a national utility PLN and a Ministry agency (DGEEU) handling the rural electrification programs. The budget comes from a specially allocated fund known as the Dana Alokasi Khusus (DAK). It is a highly useful policy tool designed by the government to make monetary transfers to the regional and district level governments, earmarked for energy access as well as other initiatives.

Multilateral Development Banks (National, regional and international)

Multilateral aid is delivered through international institutions such as the various agencies of the World Bank and the United Nations, and has a broad mandate to finance development and structural reform. Their priority is predominantly socioeconomic rather than purely commercial, which explains why they have a key role to play in filling the gaps left by governments and private companies in relation to access to energy. This is particularly true for large-scale energy projects with long maturation periods which require long-term, risky financing that commercial banks are reluctant to provide. Furthermore, many such large-scale energy projects have greater social rather than economic returns, and are therefore an obvious target for multilateral aid.In addition to addressing long-term funding needs, Development Banks can also play an important role in shaping and steering the national and regional financial development system by creating and providing financing instruments that better spread the financial risk among creditors and borrowers and over time. Furthermore, as established institutional players, development banks can influence and support a proactive national and regional development strategy and help leverage resources by attracting other lenders and providing guarantees.

Private Investors

There are many investment firms dedicated to development initiatives, including energy access. Private equity funds are also numerous and active. One example is Energy Access Ventures (EAV), which promotes low-cost and low-carbon solutions to address the lack of electrification across Sub-Saharan Africa. It specifically caters to geographical areas that cannot gain access to traditional methods of finance. Multinational corporations (MNCs) also play a significant role by either entering the industry themselves, usually by investing in local companies already present in the space, or by donating to international organizations tackling the issue. Key examples include Samsung, Schneider Electric, Caterpillar Incorporated, Ikea, Google, Microsoft and Tesla.

Bilateral aid

Bilateral aid is given by one government directly to the government of a developing country to support economic, environmental, social, and political development. Although the SDG target 17.2 reiterates developed countries’ longstanding commitment to provide 0.7 % of their gross national income (GNI) in Official Development Assistance (ODA) to developing countries, only a handful of countries, mainly from Scandinavia and northern Europe, are meeting this target.

Pilot projects

Aid effectiveness has been a hot topic in previous years. Without entering into the debate, it is clear that development aid has made it possible to fund energy pilot projects in rural communities in some of the least developed countries, which would have otherwise been impossible. While these pilot projects have only, at most, provided low levels of energy access to very few, they have served as the test and trial ground upon which some solid business cases have been built and which the private sector now is considering to scale up.

Recent political developments and continued economic stress in major donor economies, combined with the aid effectiveness debate, are causing some donors to rethink their development aid commitments, including possibly abandoning the commitment to provide 0.7 % GNI in ODA and reducing contributions to multilateral bodies such as the World Bank.

►Go to Top

Potential Solutions

We may perceive that a new development finance paradigm is emerging, one in which traditional development aid is replaced by a blend of public and private finance that includes a wider range of investors like development finance institutions, private equity managers, impact investors and institutional investors alongside NGOs and philanthropists. The result is an interlaced web of public and private interests and motivations, which has exhibited a remarkable ability to raise large amounts of development finance. In recent years we have observed a growing trend of such partnerships including the European Sustainable Development Fund, Africa-EU Energy Partnership (AEEP), ElectriFi, Africa Power Vision, Energies pour l’Afrique etc, and a large majority of them focus on the promotion of renewable energy and address the electricity sector. Furthermore, there has been a proliferation of infrastructure- and energy-specific development funding as well as the creation of climate and green financing facilities, at the bilateral, regional and multilateral level. Such initiatives are often linked to climate-change policy or sustainable development and may or may not target energy infrastructure and/or access.

Impact Investing

The field of impact investing, in particular, has made significant strides and continues to gain momentum in this domain. North American and European institutions have played a key role in the development of the industry and we are starting to see its rise in Asia. For the most part, these are private firms with strong links to the public sector, whose distinguishing factor is their desire to achieve something of intrinsic value while generating a profit. Financial and social/environmental impacts are equally important factors that contribute to the decision-making regarding companies/projects to invest in. These projects cover a range of fields, such as education, healthcare and sustainability, with renewable energy playing an increasingly important role. Most other organizations are unwilling or do not have the capacity to take on long-term investments of about 25 years, which is what the traditional grid sector has generally required. However, impact investment firms might finally provide substantial help to finding solutions to bridging the funding gap in financing energy access.

The United Nations Foundation understands the power of impact investing and created a directory of impact investing opportunities in 2013. Known as the “Energy Access Practitioner Network”, the report provides a comprehensive look at investment opportunities around the world in order to achieve universal energy access by 2030. The network comprises of more than 1,500 organizations specifically geared towards tailoring financial solutions for social enterprises in the sector. They are clear in their thinking that one size does not fit all, thus considering off-grid solutions, accounting for local conditions as well as customers’ payment capacity.For example, Schneider Electric entered the field in 2009 due to its strong belief that “impact investing will be part of the solution to close the energy gap in the coming years”. The Schneider Electric Energy Access (SEEA) fund supports small and medium businesses with innovative solutions for providing energy access to the 1.06 billion people who still lack it; Schneider also participates in the EAV mentioned above.

Political and regulatory framework

There are additional matters that need to be prioritized in order to concretely bridge the funding gap, not only from the finance side but also from the policy viewpoint. The current situation needs to be thoroughly assessed and modified based on innovative mechanisms that have quickly come into play over recent years. “Pay-as-you-go” models and microfinance institutions have achieved considerable results but need to be supplemented through other initiatives. While high/middle income countries are more likely to raise private funds, public organizations are still the best options for low income countries and must be given their due credit. Regulatory agencies are key in tracking their progress and ensuring that resources are being effectively allocated to financing mechanisms.

►Go to Top

Conclusion

Although the prospect of universal energy access may seem daunting, it is indeed achievable given the right methodologies in both finance and technology. The amount of funding needed is much higher than what is currently available. Equally as important to funding quantity, however, are the financial procedures and structures that need to be implemented to attract foreign investment in low and medium access countries. Without that, these countries will have to rely more heavily on traditional loans, grants and subsidies which may also yield results in time. Innovation in the financial sector must also play a key role in years to come as methods that have worked for traditional, grid-based systems may no longer be valid in the developing world. In conclusion, achieving the SDG7 hinges on greater and different methods of funding the energy gap.

►Go to Top

References

- IEA, World Energy Outlook 2017 Special Report, Energy Access Outlook, 2017

- World Bank, Global Tracking Framework - Progress Toward Sustainable Energy, 2017

- UNCTAD, The role of development banks in promoting growth and sustainable development in the South, 2016

- OECD, Towards a Framework for the Governance of Infrastructure, Public Governance and Territorial Development Directorate, 2015

- Florence School of Regulation, Regulation for Universal Access to Energy online course

- IIED, Unlocking climate finance for decentralized energy access, 2016

- India historic success for electricity access, future connections will be decentralized: IEA. Power for All, 2017.

- Countries Portal, Energypedia.

Further Information

- Portal:Energy Access

- Portal:Financing and Funding

- Barriers and Risks to Renewable Energy Financing

- Off-grid Energy Companies and Financial Institutions - Need and Options for Collaboration

|

This article is part of the Energy Access Portal which is a joint collaboration between energypedia UG and the “World Access to Modern Energy (WAME)". WAME is managed by the Museo Nazionale della Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci (MuST), the Fondazione AEM and the Florence School of Regulation (FSR) and it is supported by Fondazione CARIPLO. |

Written by: Pia Lovengreen Alessi, Florence School of Regulation Advisor and WAME project coordinator and Aakriti Samaiyar.