Difference between revisions of "Enhancing Production of Improved Cookstoves (ICS)"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| (65 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | [[File:GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium small.png|left|831px|GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium|alt=GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium small.png|link=GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium]]<br/><br/><!-- | |

| − | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | Cooking Energy System |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Cooking Energy Technologies and Practices|Cooking Energy System]]''' {{!}} | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Cooking Energy Technologies and Practices|Cooking Energy System]] {{!}} | }} <!-- | |

| − | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | Basics |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Basics about Cooking Energy|Basics]]''' {{!}} | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Basics about Cooking Energy|Basics]] {{!}} | }} <!-- | |

| − | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | Policy Advice |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Policy Advice on Cooking Energy|Policy Advice]]''' {{!}} | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Policy Advice on Cooking Energy|Policy Advice]] {{!}} | }} <!-- | |

| − | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | Planning |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Planning Cooking Energy Interventions|Planning]]''' {{!}} | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Planning Cooking Energy Interventions|Planning]] {{!}} | }} <!-- | |

| − | [[ | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | ICS Supply |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Designing and Implementing Improved Cookstoves .28ICS.29 Supply Interventions|Designing and Implementing ICS Supply]]''' {{!}} | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Designing and Implementing Improved Cookstoves .28ICS.29 Supply Interventions|Designing and Implementing ICS Supply]] {{!}} | }} <!-- |

| − | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | Woodfuel Supply |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Designing and Implementing Woodfuel Supply Interventions|Designing and Implementing Woodfuel Supply]]''' {{!}} | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Designing and Implementing Woodfuel Supply Interventions|Designing and Implementing Woodfuel Supply]] {{!}} | }} <!-- | |

| − | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | Climate Change |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Climate Change Related Issues|Climate Change]]''' | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Climate Change Related Issues|Climate Change]] {{!}} | }} <!-- | |

| − | + | -->{{#ifeq: {{#show: {{PAGENAME}} |?Hera category}} | Extra |'''[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Climate Change Related Issues|Extra]]''' | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium#Climate Change Related Issues|Extra]] }} | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | == Product Development<br/> == | |

| − | + | Sometimes, existing improved stoves can be further promoted by investing into scaling up interventions. However, very often there is no ready-made improved cook stove model available that adheres 100% to the specific requirements of the local conditions. Adaptation or even the development of a new product is required to find the best balance between the needs of the targeted customers, the needs of the producers, and the frame conditions of the production chain. For product development the following steps are normally necessary:<br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | <br> | + | <br/> |

| − | + | [[File:Evolution of production in a project.JPG|thumb|center|750px|Evolution of production in a project|alt=Evolution of production in a project.JPG]] | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | Prototypes of new stoves are usually produced in a lab-controlled environment with close collaboration between stove designers and researchers, stove users and potential producers. Once the prototype fulfills the required standards, it has to be field tested at a larger scale to verify if the stove performs well enough and if ordinary households are using it. In reality, there might be alterations between phases of lab testing and field testing.<br/> | |

| + | The development of an ICS is never actually completed. Even after 10 years of promotion, new materials or design features may come up. Researchers and technicians tend to request for long product development phases, whereas project managers tend to push for early piloting. There is no golden rule for identifying when a stove is ready for the market.<br/> | ||

| + | <br/><u>There are, however, some general requirements. These include:</u><br/>• The stove must be safe enough to be used in households without doing harm to the user;<br/>• The stove must perform well enough to satisfy both the potential user as well as the intention by a private or public supporter (e.g. donor) of the improved cook stove;<br/>• The stove must be convenient and appealing enough to convince the target group to buy and use it;<br/>• The cost of stove production (including material cost) must be low enough to allow a retail price which satisfies both the target group (affordability) as well as the producer (profit margin per stove and turn over).<br/> | ||

| − | + | At some stage of the development process, there is a need to interrupt the change processes for at least a year to allow a field based learning on a constant stove model. Otherwise it is difficult to identify which variation of the stove model is related to which feedback or observation. While an early release to the public bears the risk of a public failure (image problem), a prolonged research period increases the cost of development and delays the results of dissemination.<br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | == Piloting of Improved Cookstoves (ICS) Production<br/> == | |

| − | + | Once the field test confirms the satisfaction of the target group with the product, the ICS will be produced for the selected market. As there is still the danger of “teething problems” (see below) in the first few years, it is a common practice to start with a geographically restricted pilot project. This will allow a close follow-up for producers and users through “the project” to ensure that the stoves are properly produced and appropriately used. If problems with the design or the materials are arising, there is still the possibility to correct the faults before large segments of the targeted market are already dissatisfied with the product. | |

| − | + | <br/><u>The initial step from “prototyping” to “piloting production” is very crucial and difficult:</u> | |

| − | + | *we are not yet sure of the product (teething problems); | |

| + | *we are not yet sure of the market (new product); | ||

| + | *we are not yet sure of the market case (production costs vs. sales price); | ||

| + | *we are not yet sure of the marketing system. | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | Because of these uncertainties, many projects feel the need to protect the initial producers against the risks of entering this new production business. <u>This “protection” can take the form of…</u><br/> | |

| + | *providing producers with required tools; | ||

| + | *providing producers with required production materials; | ||

| + | *providing producers with grants or loans; | ||

| + | *giving producers large production contracts ( project buys all their stoves ); | ||

| + | *employ the producers ( time-based contracts); | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <u>While these interventions are useful to get the production going, there are also huge risks for the long term sustainability attached to these approaches:</u> | ||

| + | *The initial producers may consider themselves as “employees of the program”. Therefore, clarification of ownership is a must right from the beginning;<br/> | ||

| + | *If the risk to produce for the market is buffered by a program, there is little motivation for the producers to develop a cost-efficient production concept. The initial price for the stove will always be high as there is no incentive to produce many stoves in short time. As a remedy, projects tend to subsidize the initial price for the customer to still find a market for the stove. Once this system of a high workshop-gate price on the side of the producers and a project-based subsidized low customer price is established, it will be highly difficult to exit this scenario without severe fractions. If the stove price increases up to the real price after the removal of the subsidy, the customers will complain that they are used to having a cheaper stove. Or if the workshop-gate price is pushed lower, than the producers may lose interest. Unless there is a clear element of economy of scale, which will result in a natural reduction of production costs over a short time, there is no easy exit from this system.<br/> | ||

| − | + | <br/>In many countries, there are artisans who have already worked with former “stove projects”. New interventions often have to also combat expectations which are generated from these past experiences. It requires time, good knowledge of the local stove project history, and strong standing to establish a different system. The selection of the location and the initial producers is something which should be carried out with thorough planning.<br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | It is not possible to suggest “the best way” on how to initiate the ICS production as it is highly circumstantial. <u>However, here are some ideas which have worked in the past:</u><br/> | |

| − | + | *At the end of the prototype-development phase, test-sales can be done to assess how much people would pay for the stove. They can also generate orders for stoves.<br/> | |

| + | *Based on this concrete demand, artisans with an already established workshop and business can be asked if they are interested to satisfy this documented demand if trained by the program. It is assumed that these producers have all tools and labor required to manufacture the stoves. The project may give a warranty that the investment into the materials for the stoves will be covered in case the stoves are actually not sold despite the orders of the customers.<br/> | ||

| + | *Once these first stoves are produced and sold, the initial producers are invited to participate in awareness and marketing activities to establish their own links to potential target groups and understand how to find markets for their new product.<br/> | ||

| + | *They are continuously supported through quality control and additional awareness campaigns. Feedback rounds with early customers may assist to create a better understanding of the perception of the customers.<br/> | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <u>There are some lessons from previous interventions to be shared:</u><br/> | |

| − | * | + | *Do not pay artisans for attending a training workshop on stove production.<br/>Some projects pay artisans for attending training courses as “they cannot afford to lose a working days income by attending a training course without pay”. But if you pay for participation, people will attend for the money (as a job) and you do not get the interested people. At least their time should be their contribution into a better future. You can buffer the “income-argument” by providing food and by designing half-day trainings close to the homes or work-places of the participants. Hence they can still work half time in their work-shops and still earn a little money.<br/> |

| − | * | + | *Do not provide free tooling and free materials to kick-start production:<br/>Access to tools and materials for the production of the new product might be a bottleneck for the newly trained producers. Hence it is tempting to provide them with all tools necessary and the materials required for the first number of stoves with the idea that they can afford to purchase the next materials from the income of the first stoves.<br/>In some cases this works out fine. But sometimes this attracts the wrong participants who are using the provided inputs to produce any type of other product and afterwards claim that they have to be given another material for the stoves. To avoid this kind of frustration, another option is to provide tools and inputs on a cost sharing arrangement, and the part to be paid by the artisan can be pre-financed by a micro-credit organization. This goes along with the support of the project to connect the artisans with their first customers. By doing so, a strong motivation to produce stoves is generated.<br/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Scaling-up of Improved Cookstoves (ICS) Production Capacities<br/> == | |

| − | + | Once an initial ICS production is established and the market case has been proven by an increasing demand, there is a need to scale-up the production to satisfy larger customer groups. | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <u>It is important to consider the coordinated growth of both production and demand:</u><br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *demand without products can frustrate the customers and<br/> | |

| + | *production without markets ruins the producers.<br/> | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <u>Scaling-up can be done in two dimensions:</u><br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''1. Increasing the number of small scale supply-demand systems.'''<br/> | |

| − | + | In this case, the concept of “local production for local markets based on local resources and local skills” is maintained. It is a concept which provides a close link between producers and users and is relatively robust against external shocks. For scaling-up this concept, a large effort in capacity building for many artisans is required. Strong and organised partners are needed, who know both the country and its people very well, allowing the project to act as a facilitator. Involvement with other organisations, such as NGOs, the private sector, or governmental bodies, is a precondition for achieving sustainable access to household energy for large numbers of people. These already existing partners can be found in many sectors which are related to cooking energy.<br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | '''2. Inreasing productivity of production systems'''<br/> | |

| − | + | Another way of increasing the production is the transformation of the existing production system to increase the productivity per producer. This can be based on the introduction of improved tooling (e.g. in Senegal the introduction of flanging, bending and rounding machines for metal works) of local artisans or the establishment of semi-industrial production centers (e.g. introduction of an extruder machine for the production of ceramic liners in Ethiopia).<br/> | |

| − | + | <u>The investment into machinery has various dimensions:</u><br/> | |

| − | <br> | + | *The investment has to be financed: there might be a need to support the producers through [[Financing Mechanisms for Cookstove Dissemination|micro-finance instruments]] to facilitate the investment.<br/> |

| + | *The investment must be viable: the additional costs of the investment must be overcompensated by additional income through cheaper production and increase of sales. A business case study for such an investment should be produced before the investment is executed.<br/> | ||

| + | *Staff qualification: new machines require new skills and knowledge. Existing staff has to be trained or better staff has to be recruited to operate the new machines properly. | ||

| + | *The investment can increase the vulnerability of the production: If new machines depend on the availability of electricity or the presence of a specific (qualified) staff member, the production might be more vulnerable for forced interruptions. The risks of such vulnerabilities should be assessed upfront.<br/> | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Donors and Institutions as Customers<br/> == | |

| − | + | Donors such as the '''United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)''', the '''World Food Program (WFP)''', or international NGOs supporting school feeding programmes are potential customers for stoves. | |

| − | + | Institutional stoves can be highly efficient, and their very high savings potential means that institutions (both public and private) spend less on wood fuel, and, for instance, school children spend less time collecting firewood, so more time can be spent in education. Canteens in institutions such as schools, hospitals, or prisons benefit from energy saving stoves. A cost-benefit analysis in Malawi has shown that the use of Institutional Rocket Stoves is profitable in a wide range of institutions. | |

| − | + | Also, an impact study of rocket stove in school canteens highlighted the relevance of proper and practical user training not only of head teachers or coordinators but of the cooks themselves. Read more: [[:File:ProBEC_Study_on_the_Impact_of_the_Institutional_Rocket_Stoves_in_School_Kitchens.pdf|ProBEC Study on the Impact of the Institutional Rocket Stoves in School Kitchens]]. | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | {| style="width: 100%" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="4" border="1" | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | colspan="4" bgcolor="#e0e0e0" | | |

| − | + | '''Institutional rocket stoves in Malawi'''<br/>An orphanage that prepares two meals a day in a 100 litre pot saves 680 US$ yearly on firewood expenditures. If a 200 litre stove is used twice a day throughout the whole year the net benefit during the stove’s four-year life is 4235 US$. Depending on cooking frequency and size, the price for a stove has been paid off after three to nine months. Due to reduced firewood costs canteens save up to 40% on their catering budget.<br/>-> [[:file:Costs-benefits-institutional-stoves malawi-probec-2008.pdf|CBA Malawi Costs and Benefits of Institutional Stoves]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | |} | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | {| style="width: 100%" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="4" border="1" | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | <br> | + | | colspan="4" bgcolor="#e0e0e0" | '''Application of Improved Cooking Stoves in Rural Health Centers'''<br/><div><u>Cooking needs in rural health centers can be divided into two categories, depending on the target group, for whom the food is prepared:</u><br/></div> |

| − | + | *'''Food for staff'''<br/>It depends mainly on the number of staff, the health center management, and/or the degree of self-organization of the staff. If the meals for staff members are prepared communally, an institutional size stoves might make sense.<br/>Examples: Both Mission and the Government hospitals in Mulanje District (Southern Malawi) have institutional size wood-fired rocket stoves to cater for the staff and the students of the nursing college. Cooking is done by a paid cook, who got trained on the proper use of the stoves. The firewood is provided by the hospital. Savings as compared to the open fire are between 70-80 percent. | |

| − | + | *'''Food for patients'''<br/>Most rural health centers do not provide meals for the patients, even if they have in-patient facilities. The meals for patients are prepared individually by the guardians who accompany the patient often with the main purpose to cater or prepare warm bath water for the patient. Thus individual cooking facilities are needed for the guardians. Usually food ingredients, fuel, and cooking utensils have to be organised by the guardians and are not provided by the health center. Thus, the most prevalent cooking facility is the makeshift 3-stone fire fuelled with firewood or any other biomass that the guardians are able to organise in the immediate surroundings of the health center. A good practice is when health centers provide a sheltered cooking place and define the area where cooking is allowed. To minimise the adverse effects of air pollution and prevent smoke from adding to the ailments of the patients, this location should preferably be at a distance from the wards and care units. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <br> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | Mulanje Mission Hospital in Southern Malawi went even further. They had already a roofed kitchen for the guardians with 20 simple fireplaces. As hospital facilities were expanding and the number of in-patients increasing, the kitchen became small.<br/>With advice from GIZ-project staff on stove technology and kitchen design, they added another roofed kitchen with improved fixed ‘Epseranza’ -type stoves and good ventilation. In the first weeks the kitchen was not yet well accepted and rather empty, because people were not familiar with the stoves and were unsure how to use them. Upon realizing this, a permanent security staff of the hospital got trained on the correct stove use and was able to show the ever-changing users, who normally don’t use the kitchen longer than a few days. From then on, the kitchen became more and more popular as people became aware of he advantages: the new stoves were more economic, cooked faster, created less smoke, and the building had a better ventilation. Young mothers felt more comfortable bringing their babies in the new kitchen. The challenge remains to organise the maintenance of the stoves, as some of the ceramic pot-supports of the ‘Esperanza stoves’ went missing and the stoves perform poorly without them. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | <br> | + | <br/>Cooperation with Ministries of Education can further help selling stoves and may offer the opportunity to incorporate household energy into curricula. For example, testing sites at Ethiopian schools offer students and teachers the option of learning more about cooking energy and the dangers involved from smoke inhalation. Programmes for improved housing are potential partners if they provide access to stoves to their beneficiaries. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | For | + | For these initiatives to happen, organisations must be informed about the project and the technology options the producers offer. When the product is launched, it may be necessary to create links between these institutions and the stove producers, and facilitate communication through meetings and workshops. |

| − | + | Experience in Malawi has shown that even if stoves are bought ‘off the counter’ from the producer, training sessions for the purchasers should be part of the package. Correct stove use is crucial for fuel savings, and for the longevity of the device. This also leads to happy customers and successful producers. Voluntary staff often do the cooking at social institutions such as orphanages. Howeve, they may have no experience with fuel-efficient stoves and would benefit from on-site training on how to use the stoves properly. This training can be done either by the project itself or by the institution. In the longer term, it is better for the institution itself to be trained by the project, so that it can train its own staff in the future. | |

| − | < | + | <br/> |

| − | + | '''Industries as customers and development partners'''<br/>Large companies catering for their workers usually cook several hundreds or even thousands of meals every day – often on traditional stoves. Using a fuel efficient cooking technology is very cost effective in such circumstances, and the savings can cover the cost of the stove very quickly. Experience in Malawi has shown that canteens in tea estates or sugar plantations can reduce their fuelwood consumption to 10% of the quantity used on an open fire (a 90% reduction). Companies such as these may be willing to act as development partners by agreeing to test different models in their canteens. | |

| − | + | Many companies also provide their staff with housing and other services. Access to energy can be incorporated into corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives through public/private partnerships (PPP) or similar types of cooperation. Ideally, this is a win-win situation. Risks and costs of research and development, and the cost of improving the house through improved technologies, can be shared between the project and the industry. The agricultural industry (sugar, tea, tobacco) has shown particular interest in CSR activities that involve access to clean, efficient energy, as their corporate social responsibility actions can enable them to achieve a fair trade label. | |

| − | + | -> [[:file:En-probec institutional stoves mw-2007.pdf|ProBEC presentation ‘Institutional Stoves’ with experiences from Malawi]] | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | = Further reading<br/> = | |

| − | + | For over three decades, Aprovecho Research Center has been the global go-to for practical, efficient, and purposeful expertise in the design and testing of biomass cookstoves. Their leading-edge and collaborative research continues to remain open source and accessible to promote the “best use of” resources for everyone from the rural cook to national governments. [http://aprovecho.org/ http://aprovecho.org/]<br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | = References<br/> = | |

| − | + | This article was originally published by [http://www.giz.de/fachexpertise/html/2769.html GIZ HERA]. It is basically based on experiences, lessons learned and information gathered by GIZ cook stove projects. You can find more information about the authors and experts of the original “Cooking Energy Compendium” in the [[Imprint - GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium|Imprint]]. | |

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium|--> Back to Overview GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium]] | |

| − | + | {{#set: Hera category=ICS Supply}} | |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Cooking_Energy_Compendium_(GIZ_HERA)]] |

| + | [[Category:Improved_Cooking]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Cookstoves]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Cooking_Energy]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:39, 10 September 2020

Cooking Energy System | Basics | Policy Advice | Planning | Designing and Implementing ICS Supply | Designing and Implementing Woodfuel Supply | Climate Change | Extra

Product Development

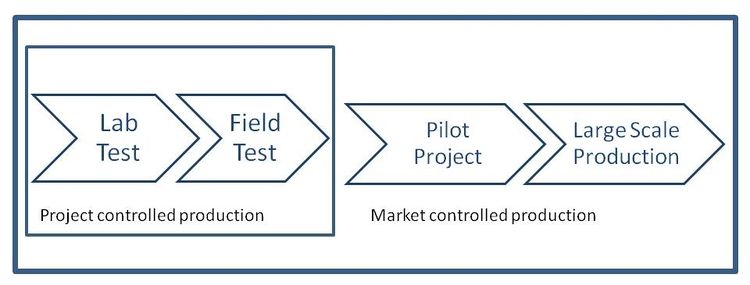

Sometimes, existing improved stoves can be further promoted by investing into scaling up interventions. However, very often there is no ready-made improved cook stove model available that adheres 100% to the specific requirements of the local conditions. Adaptation or even the development of a new product is required to find the best balance between the needs of the targeted customers, the needs of the producers, and the frame conditions of the production chain. For product development the following steps are normally necessary:

Prototypes of new stoves are usually produced in a lab-controlled environment with close collaboration between stove designers and researchers, stove users and potential producers. Once the prototype fulfills the required standards, it has to be field tested at a larger scale to verify if the stove performs well enough and if ordinary households are using it. In reality, there might be alterations between phases of lab testing and field testing.

The development of an ICS is never actually completed. Even after 10 years of promotion, new materials or design features may come up. Researchers and technicians tend to request for long product development phases, whereas project managers tend to push for early piloting. There is no golden rule for identifying when a stove is ready for the market.

There are, however, some general requirements. These include:

• The stove must be safe enough to be used in households without doing harm to the user;

• The stove must perform well enough to satisfy both the potential user as well as the intention by a private or public supporter (e.g. donor) of the improved cook stove;

• The stove must be convenient and appealing enough to convince the target group to buy and use it;

• The cost of stove production (including material cost) must be low enough to allow a retail price which satisfies both the target group (affordability) as well as the producer (profit margin per stove and turn over).

At some stage of the development process, there is a need to interrupt the change processes for at least a year to allow a field based learning on a constant stove model. Otherwise it is difficult to identify which variation of the stove model is related to which feedback or observation. While an early release to the public bears the risk of a public failure (image problem), a prolonged research period increases the cost of development and delays the results of dissemination.

Piloting of Improved Cookstoves (ICS) Production

Once the field test confirms the satisfaction of the target group with the product, the ICS will be produced for the selected market. As there is still the danger of “teething problems” (see below) in the first few years, it is a common practice to start with a geographically restricted pilot project. This will allow a close follow-up for producers and users through “the project” to ensure that the stoves are properly produced and appropriately used. If problems with the design or the materials are arising, there is still the possibility to correct the faults before large segments of the targeted market are already dissatisfied with the product.

The initial step from “prototyping” to “piloting production” is very crucial and difficult:

- we are not yet sure of the product (teething problems);

- we are not yet sure of the market (new product);

- we are not yet sure of the market case (production costs vs. sales price);

- we are not yet sure of the marketing system.

Because of these uncertainties, many projects feel the need to protect the initial producers against the risks of entering this new production business. This “protection” can take the form of…

- providing producers with required tools;

- providing producers with required production materials;

- providing producers with grants or loans;

- giving producers large production contracts ( project buys all their stoves );

- employ the producers ( time-based contracts);

While these interventions are useful to get the production going, there are also huge risks for the long term sustainability attached to these approaches:

- The initial producers may consider themselves as “employees of the program”. Therefore, clarification of ownership is a must right from the beginning;

- If the risk to produce for the market is buffered by a program, there is little motivation for the producers to develop a cost-efficient production concept. The initial price for the stove will always be high as there is no incentive to produce many stoves in short time. As a remedy, projects tend to subsidize the initial price for the customer to still find a market for the stove. Once this system of a high workshop-gate price on the side of the producers and a project-based subsidized low customer price is established, it will be highly difficult to exit this scenario without severe fractions. If the stove price increases up to the real price after the removal of the subsidy, the customers will complain that they are used to having a cheaper stove. Or if the workshop-gate price is pushed lower, than the producers may lose interest. Unless there is a clear element of economy of scale, which will result in a natural reduction of production costs over a short time, there is no easy exit from this system.

In many countries, there are artisans who have already worked with former “stove projects”. New interventions often have to also combat expectations which are generated from these past experiences. It requires time, good knowledge of the local stove project history, and strong standing to establish a different system. The selection of the location and the initial producers is something which should be carried out with thorough planning.

It is not possible to suggest “the best way” on how to initiate the ICS production as it is highly circumstantial. However, here are some ideas which have worked in the past:

- At the end of the prototype-development phase, test-sales can be done to assess how much people would pay for the stove. They can also generate orders for stoves.

- Based on this concrete demand, artisans with an already established workshop and business can be asked if they are interested to satisfy this documented demand if trained by the program. It is assumed that these producers have all tools and labor required to manufacture the stoves. The project may give a warranty that the investment into the materials for the stoves will be covered in case the stoves are actually not sold despite the orders of the customers.

- Once these first stoves are produced and sold, the initial producers are invited to participate in awareness and marketing activities to establish their own links to potential target groups and understand how to find markets for their new product.

- They are continuously supported through quality control and additional awareness campaigns. Feedback rounds with early customers may assist to create a better understanding of the perception of the customers.

There are some lessons from previous interventions to be shared:

- Do not pay artisans for attending a training workshop on stove production.

Some projects pay artisans for attending training courses as “they cannot afford to lose a working days income by attending a training course without pay”. But if you pay for participation, people will attend for the money (as a job) and you do not get the interested people. At least their time should be their contribution into a better future. You can buffer the “income-argument” by providing food and by designing half-day trainings close to the homes or work-places of the participants. Hence they can still work half time in their work-shops and still earn a little money. - Do not provide free tooling and free materials to kick-start production:

Access to tools and materials for the production of the new product might be a bottleneck for the newly trained producers. Hence it is tempting to provide them with all tools necessary and the materials required for the first number of stoves with the idea that they can afford to purchase the next materials from the income of the first stoves.

In some cases this works out fine. But sometimes this attracts the wrong participants who are using the provided inputs to produce any type of other product and afterwards claim that they have to be given another material for the stoves. To avoid this kind of frustration, another option is to provide tools and inputs on a cost sharing arrangement, and the part to be paid by the artisan can be pre-financed by a micro-credit organization. This goes along with the support of the project to connect the artisans with their first customers. By doing so, a strong motivation to produce stoves is generated.

Scaling-up of Improved Cookstoves (ICS) Production Capacities

Once an initial ICS production is established and the market case has been proven by an increasing demand, there is a need to scale-up the production to satisfy larger customer groups.

It is important to consider the coordinated growth of both production and demand:

- demand without products can frustrate the customers and

- production without markets ruins the producers.

Scaling-up can be done in two dimensions:

1. Increasing the number of small scale supply-demand systems.

In this case, the concept of “local production for local markets based on local resources and local skills” is maintained. It is a concept which provides a close link between producers and users and is relatively robust against external shocks. For scaling-up this concept, a large effort in capacity building for many artisans is required. Strong and organised partners are needed, who know both the country and its people very well, allowing the project to act as a facilitator. Involvement with other organisations, such as NGOs, the private sector, or governmental bodies, is a precondition for achieving sustainable access to household energy for large numbers of people. These already existing partners can be found in many sectors which are related to cooking energy.

2. Inreasing productivity of production systems

Another way of increasing the production is the transformation of the existing production system to increase the productivity per producer. This can be based on the introduction of improved tooling (e.g. in Senegal the introduction of flanging, bending and rounding machines for metal works) of local artisans or the establishment of semi-industrial production centers (e.g. introduction of an extruder machine for the production of ceramic liners in Ethiopia).

The investment into machinery has various dimensions:

- The investment has to be financed: there might be a need to support the producers through micro-finance instruments to facilitate the investment.

- The investment must be viable: the additional costs of the investment must be overcompensated by additional income through cheaper production and increase of sales. A business case study for such an investment should be produced before the investment is executed.

- Staff qualification: new machines require new skills and knowledge. Existing staff has to be trained or better staff has to be recruited to operate the new machines properly.

- The investment can increase the vulnerability of the production: If new machines depend on the availability of electricity or the presence of a specific (qualified) staff member, the production might be more vulnerable for forced interruptions. The risks of such vulnerabilities should be assessed upfront.

Donors and Institutions as Customers

Donors such as the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Program (WFP), or international NGOs supporting school feeding programmes are potential customers for stoves.

Institutional stoves can be highly efficient, and their very high savings potential means that institutions (both public and private) spend less on wood fuel, and, for instance, school children spend less time collecting firewood, so more time can be spent in education. Canteens in institutions such as schools, hospitals, or prisons benefit from energy saving stoves. A cost-benefit analysis in Malawi has shown that the use of Institutional Rocket Stoves is profitable in a wide range of institutions.

Also, an impact study of rocket stove in school canteens highlighted the relevance of proper and practical user training not only of head teachers or coordinators but of the cooks themselves. Read more: ProBEC Study on the Impact of the Institutional Rocket Stoves in School Kitchens.

|

Institutional rocket stoves in Malawi |

| Application of Improved Cooking Stoves in Rural Health Centers Cooking needs in rural health centers can be divided into two categories, depending on the target group, for whom the food is prepared:

Mulanje Mission Hospital in Southern Malawi went even further. They had already a roofed kitchen for the guardians with 20 simple fireplaces. As hospital facilities were expanding and the number of in-patients increasing, the kitchen became small. |

Cooperation with Ministries of Education can further help selling stoves and may offer the opportunity to incorporate household energy into curricula. For example, testing sites at Ethiopian schools offer students and teachers the option of learning more about cooking energy and the dangers involved from smoke inhalation. Programmes for improved housing are potential partners if they provide access to stoves to their beneficiaries.

For these initiatives to happen, organisations must be informed about the project and the technology options the producers offer. When the product is launched, it may be necessary to create links between these institutions and the stove producers, and facilitate communication through meetings and workshops.

Experience in Malawi has shown that even if stoves are bought ‘off the counter’ from the producer, training sessions for the purchasers should be part of the package. Correct stove use is crucial for fuel savings, and for the longevity of the device. This also leads to happy customers and successful producers. Voluntary staff often do the cooking at social institutions such as orphanages. Howeve, they may have no experience with fuel-efficient stoves and would benefit from on-site training on how to use the stoves properly. This training can be done either by the project itself or by the institution. In the longer term, it is better for the institution itself to be trained by the project, so that it can train its own staff in the future.

Industries as customers and development partners

Large companies catering for their workers usually cook several hundreds or even thousands of meals every day – often on traditional stoves. Using a fuel efficient cooking technology is very cost effective in such circumstances, and the savings can cover the cost of the stove very quickly. Experience in Malawi has shown that canteens in tea estates or sugar plantations can reduce their fuelwood consumption to 10% of the quantity used on an open fire (a 90% reduction). Companies such as these may be willing to act as development partners by agreeing to test different models in their canteens.

Many companies also provide their staff with housing and other services. Access to energy can be incorporated into corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives through public/private partnerships (PPP) or similar types of cooperation. Ideally, this is a win-win situation. Risks and costs of research and development, and the cost of improving the house through improved technologies, can be shared between the project and the industry. The agricultural industry (sugar, tea, tobacco) has shown particular interest in CSR activities that involve access to clean, efficient energy, as their corporate social responsibility actions can enable them to achieve a fair trade label.

-> ProBEC presentation ‘Institutional Stoves’ with experiences from Malawi

Further reading

For over three decades, Aprovecho Research Center has been the global go-to for practical, efficient, and purposeful expertise in the design and testing of biomass cookstoves. Their leading-edge and collaborative research continues to remain open source and accessible to promote the “best use of” resources for everyone from the rural cook to national governments. http://aprovecho.org/

References

This article was originally published by GIZ HERA. It is basically based on experiences, lessons learned and information gathered by GIZ cook stove projects. You can find more information about the authors and experts of the original “Cooking Energy Compendium” in the Imprint.