Enhancing Production of Improved Cookstoves (ICS)

==> Back to Overview GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium

Product development

In the planning process, the targeted market segment for the promotion of ICS has been identified. Sometimes existing improved stoves can be further promoted by investing into scaling-up interventions. However, often there is no ready-made improved cook stove model available that adheres 100% to the specific requirements of this market. Adaptation or even the development of a new product is required to find the best balance between the needs of the targeted customers, the needs of the producers and the frame conditions of the production chain.

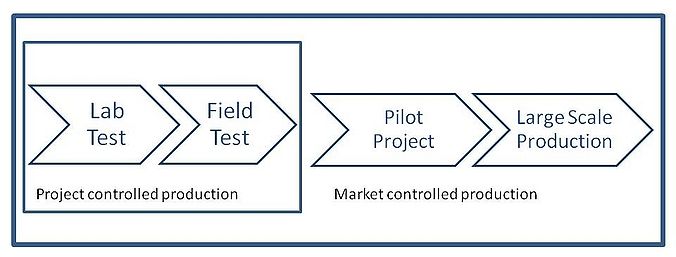

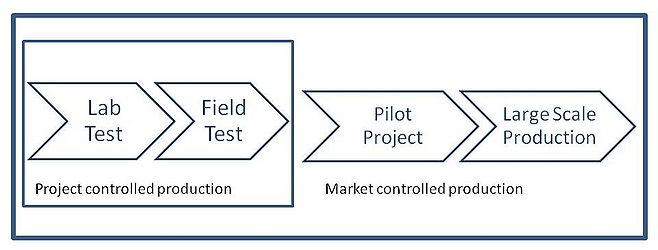

In the phase of product-development or –adaptation, the production of the ICS is controlled by “the project”. Once the ICS is ready for field testing and market introduction, the control of the production is gradually handed over to the market forces. This transition is very difficult and many projects failed due to the incompatibility between the project- and the market controlled production systems.

Prototypes of new stoves are usually produced in a lab-controlled environment with close collaboration between craftsmen, researchers and stove users. Once the prototype fulfills the required standards, it has to be field tested at a larger scale to verify if the stove performs well enough if ordinary households are using it. In reality, there might be alterations between phases of lab testing and field testing. In this period, production is controlled by the project. Market forces do not yet play a role.

The development of an ICS is actually never completed. Even after 10 years of promotion, new materials or design features may come up. Researchers and technicians tend to request for long product development phases, whereas project managers tend to push for early piloting. There is no golden rule to identify when a stove is ready for the market. But there are some general requirements:

• The stove must be safe enough to be used in households without doing harm to the user;

• The stove must perform well enough to satisfy both the potential user as well as the project indicators for “improved cook stoves”;

• The stove must be convenient and appealing enough to convince the target group to buy and use it;

• The stove must be easy to produce (simple tooling and available materials) if the product is targeting a poor population group;

• The cost of stove production (including material cost) must be low enough to allow a retail price which satisfies both the target group (affordability) as well as the producer (profit margin per stove and turn over).

At some stage of the development process there is need to interrupt the change processes for at least a year to allow a field based learning on a constant stove model. Otherwise it is difficult to identify which variation of the stove model is related to which feedback or observation. While an early release to the public bears the risk of a public failure (image problem), a prolonged research period increases the cost of development and delays the results of dissemination.

Piloting of ICS production

Once the field test confirms the satisfaction of the target group with the product, the ICS will be produced for the selected market. As there is still the danger of “teething problems” in the first few years, it is a common practice to start with a geographically restricted pilot project. This will allow a close follow-up or producers and users through “the project” to ensure that the stoves are properly produced and appropriately used. If problems with the design or the materials are arising, there is still the possibility to correct the faults before large segments of the targeted market are already dissatisfied with the product.

The initial step from “prototyping” to “piloting production” is very crucial and difficult. On the one hand:

• we are not yet sure of the product (teething problems);

• we are not yet sure of the market (new product);

• we are not yet sure of the market case (production costs vs. sales price);

• we are not yet sure of the marketing system.

Because of these uncertainties, many projects feel the need to protect the initial producers against the risks of entering this new production business. This “protection” can take the form of…

• providing producers required tools;

• providing producers required production materials;

• providing producers grants or loans;

• giving producers large production contracts (= project buys all the stoves of them);

• employ the producers (=time-based contracts);

While these interventions are useful to get the production going, there are also huge risks for the long term sustainability attached to these approaches.

• The initial producers may consider themselves as “employees of the program” and therefore the program will have to provide a market for the stove/ has to market the stoves for them;

• These “special conditions” for the early producers cannot be maintained on the long run, if sustainable supply-demand systems are the envisaged goal of the intervention. Hence producers who will be trained later will not benefit in the same way as the initial producers. But the knowledge about the initial conditions will spread fast, leading to constant jealousy between old and new producers and demands for support by the “disadvantaged” producers;

• If the risk to produce for the market is buffered by the project, there is little motivation for the producers to develop a cost-efficient production concept. The initial price for the stove will always be high as there is no incentive to produce many stoves in short time. As a remedy, projects tend to subsidies the initial price for the customer to still find a market for the stove. Once this system of a high workshop-gate price on the side of the producers and a project-based subsidized low customer price is established, it will be highly difficult to exit this scenario without severe fractions. If the stove price increases up to the real price after the removal of the subsidy, the customers will complain that they are used to have a cheaper stove. Or the workshop-gate price is pushed lower, than the producers may lose interest. Unless there is a clear element of economy of scale which will result in a natural reduction of production costs over a short time, there is no easy exit of this system.

In many countries, there are artisans who worked already with former “stove projects”. New interventions often have also to combat expectations which are generated from these past experiences. It requires time, good knowledge of the local stove project history and strong standing to establish a different system. The selection of the location and the initial producers is something which should be done based on thorough planning.

It is not possible to suggest “the best way” on how to initiate the ICS production as it is highly circumstantial. However, here are some ideas which have worked in the past:

• At the end of the prototype-development phase, test-sales can be done to assess what would people pay for the stove. They can also generate orders for stoves.

• Based on this concrete demand, artisans with an already established workshop and business can be asked if they are interested to satisfy this documented demand if trained by the program. It is assumed that these producers have all tools and labor required to manufacture the stoves. The project may give a warranty that the investment into the materials for the stoves will be covered in case the stoves actually are not sold despite the orders of the customers.

• Once these first stoves are produced and sold, the initial producers are invited to participate in awareness and marketing activities to establish their own links to potential target groups and understand how to find markets for their new product.

• They are continuously supported through quality control and additional awareness campaigns. Feedback rounds with early customers may assist to create a better understanding of the perception of the customers.

There are some lessons from previous interventions to be shared:

• Do not pay artisans for attending a training workshop on stove production.

Some projects pay artisans for attending training courses as “they cannot afford to lose a working days income by attending a training course without pay”. But if you pay for participation, people will attend for the money (as a job) and you do not get the interested people. At least their time should be their contribution into a better future. You can buffer the “income-argument” by providing food and by designing half-day trainings close to the homes or work-places of the participants. Hence they can still work half time in their work-shops and still earn a little money.

• Do not provide free tooling and free materials to kick-start production:

Access to tools and materials for the production of the new product might be a bottleneck for the newly trained producers. Hence it is tempting to provide them with all tools necessary and the materials required for the first number of stoves with the idea that they can afford to purchase the next materials from the income of the first stoves.

In some cases this works out fine. But sometimes this attracts the wrong participants who are using the provided inputs to produce any type of other product and afterwards claim that they have to be given another material for the stoves. To avoid this kind of frustration, another option is to provide tools and inputs on a cost sharing arrangement, and the part to be paid by the artisan can be pre-financed by a micro-credit organization. This goes along with the support of the project to connect the artisans with their first customers. By doing so, there is a strong motivation to produce stoves is generated.

Scaling-up of ICS production capacities

Once an initial ICS production is established and the market case has been proven by an increasing demand, there is need to scale-up the production to satisfy larger customer groups.

It is important to consider the coordinated growth of both production and demand, as

• demand without products is frustrating the customers and

• production without markets ruins the producers.

Scaling-up can be done in two dimensions:

1. Increasing the number of small scale supply-demand systems

In this case the concept of “local production for local markets based on local resources and local skills” is maintained. It is a concept which provides a close link between producers and users and is relatively robust against external shocks. For the scaling-up of this concept, a large effort in capacity building for many artisans is required. There are good examples for this approach: the “training of trainers” (hier könnte man eine powerpoint verlinken; Lisa) concept in Uganda.

Another Approach is the “mainstreaming concept” of the Program for Biomass Energy Conservation (ProBEC) in Malawi. It is based on the assessment that supporting a nation-wide dissemination is too large a task to be accomplished by a single project team. Strong and organised partners are needed, who know both the country and its people very well, allowing the project to act as a facilitator. Involvement with other organisations, such as NGOs, the private sector, or governmental bodies, is a precondition for achieving sustainable access to household energy for large numbers of people. These already existing partners can be found in many sectors which are related to cooking energy. The next figure illustrates fields and sectors where cooking energy could be incorporated into the activities of sectors other than energy.

energypedia.info/index.php/File:Jetzt.JPG

Health, forestry and food are all linked to household energy. Source: GTZ ProBEC.

2. Increasing productivity of production systems

Another way of increasing the production is the transformation of the existing production system to increase the productivity per producer. This can be based on the introduction of improved tooling (e.g. in Senegal the introduction of flanging, bending and rounding machines for metal works) of local artisans or the establishment of semi-industrial production centers (e.g. introduction of an extruder machine for the production of ceramic liners in Ethiopia).

The challenge of this approach is the financing of the investment costs. While the new equipment reduces the production costs, the savings per stove might not be sufficient to pay back the investment costs in a reasonable time span.

Identification of potential ICS markets

The inception study informs the planning process about many aspects:

- Potential project locations

- Potential implementation partners

- Potential useful technologies

- Potential production and marketing concepts

- Political frame conditions for ICS production and marketing

The result of the inception study needs to be verified by important stakeholders, which is usually done in a national stakeholder workshop. As a result of this workshop, potential ICS markets can be described by aspects of:

- Type of customer

- Geographical intervention area

- Characteristics of required technology

- Potential options for production and marketing

Sometimes it is useful to prepare such business cases already upfront and discuss and rank these scenarios at the stakeholder workshop.

It is important to bear in mind that a cooking systems is more than just a financial consideration. It often requires a change of behavior which is difficult to achieve.

The core question is “Why should poor people spend their little cash for an ICS?”

- Financial issues: Investment cost, cost of usage, durability;

- Convenience issues: handling, intensity of attention to the fire, traditional meals, size and height, emissions of heat/light/smoke;

- Status issues: design, modernity, aspirational products;

- Access and vulnerability issues: Can we trust this new product? What does it mean to me if I buy it and than it does not work/I cannot access the fuel (e.g. supply shortage of imported parts or fuels)?

This question has to be answered through the perspective of the potential buyers to investigate if there is a business case. User group discussions or test sales can assist to verify the strength of an ICS market case.

The potential ICS markets can be ranked in various dimensions:

- Purchase power of customer groups;

- Size of the market;

- Access of potential customers to the market / Difficulty to reach customers;

- Likeliness to find a product that suits the demand of the potential customers (existing product or need for product development);

- Competition on the market through other players;

- possibility to scale up existing efforts.

Based on these (and other) criteria, the potential ICS markets can be prioritized. However, it needs to be verified if the “best market” is also relevant from the perspective of the underlying development goals.

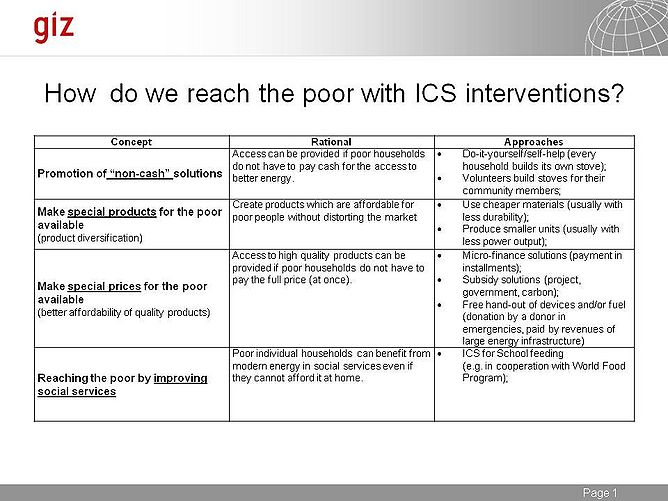

“How do we reach ‘the poor’ with our ICS interventions?”

Poverty reduction is the overarching goal of any development intervention. However, there can be huge difference between ‘directly addressing the needs of the poor’ and concepts where poverty reduction is an effect at the outer end of the result chain.

The first step is to agree who should be considered poor in the given environment. Usually there is a strata within “the poor” which can be instrumental in the process of identifying the right target group.

Generally, four concepts of how to address specifically very poor target groups can be distinguished:

1. Promotion of “non-cash” solutions

2. Make “special products” for the poor available

3. Make “special prices” for the poor available

4. Reaching the poor by improving social services

Each of these concepts has its specific rational and approaches.

At some stage there seems to be a trade-off between poverty orientation and sustainability. While “non-cash” self-help stoves and highly subsidized stoves may allow to reach fast many very poor people, the development of special products (to be sold at commercial rates) or the support through improved social services may result on the long run into more sustainable benefits for the poor.

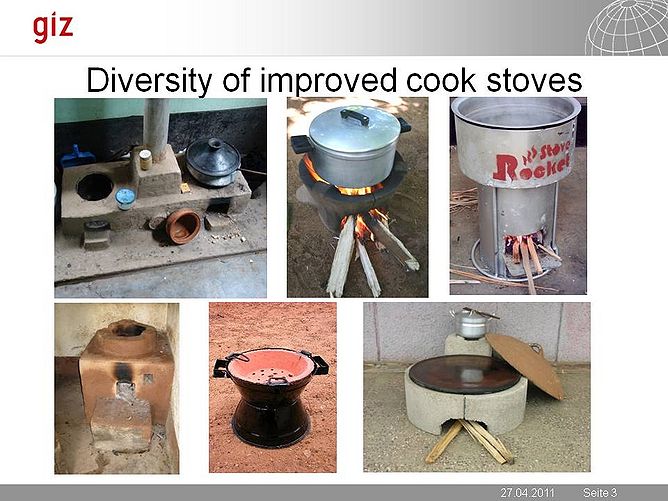

Technology selection

A wide range of improved cook stoves have been developed and disseminated in the past 30 years.

They differ in many aspects:

- Fuel: firewood, charcoal, other non-tree solid biomass, liquid biomass, gas from biomass, non-biomass fuels;

- Mobility: portable or fixed stoves

- Flames: one flame stove or multiple flame stove

- Pots: (a) ‘one pot only at a time’ or ‘multiple pots used at the same time’; (b) only usable for a specific pot (sunken pot concept) or usable for a variety of pot sizes and shapes;

- Material: (a) mud, fired clay, bricks, cement/concrete, metal, isolation materials (vermiculite, ceramic wool, refractory bricks, air…) (b) one material or material mix;

- Chimney: smoke reduction (without chimney) or smoke extraction (with chimney);

- Dimension: Tea preparation stove (for app. 1-2l), household size stove (for app. 3-15l), restaurant size (for app. 15-50l), large institutional stove (for app. 50-300l)

All these differences impact on the perception of the “convenience of use” by potential user groups.

An overview on ICS examples is given in chapter “cooking energy technologies and practices”.

There is no standard procedure to identify which technology option might be most successful on the market. On the one hand it has often been observed that “evolution” of existing baseline technologies is more acceptable and feasible than “revolution” (e.g. bringing in a completely new stove and fuel concept). On the other hand, the establishment of a commercial supply chain might be more feasible with a “modern/strange” product (e.g. a portable metal stove) rather than with a modification of an existing self-help product (e.g. an improve mud stove), if there is already a long tradition of local non-cash stove building.

Many interventions resorted into offering a range of stoves to the target groups and let them have the choice according to their needs, capabilities and preferences. Sometimes you start with one or two products and then, after realizing additional market opportunities, additional products are taken on board.

In the selection of technologies, the needs and perception of both potential customers and users on the one hand and potential producers and traders on the other hand have to be taken into consideration.

- A stove which works well and is very cheap, but which will not give the producer any profit, will not be produced for sale.

- A high-end efficient, durable and beautiful stove which is highly profitable for the producer will not be effective if the target group is not prepared to spend so much money for its purchase.

Both sides should be involved in the selection process of the technology.

New technologies often have to be adapted to the local requirements. It is important to reserve time and resources for several loops between producers and users of a new ICS to make sure that the stove model is well accepted and matured before the actual market introduction. Although this sounds trivial, in the reality there are tremendous time pressures which suggest taking some short cuts. However, this might be the wrong place to cut corners.

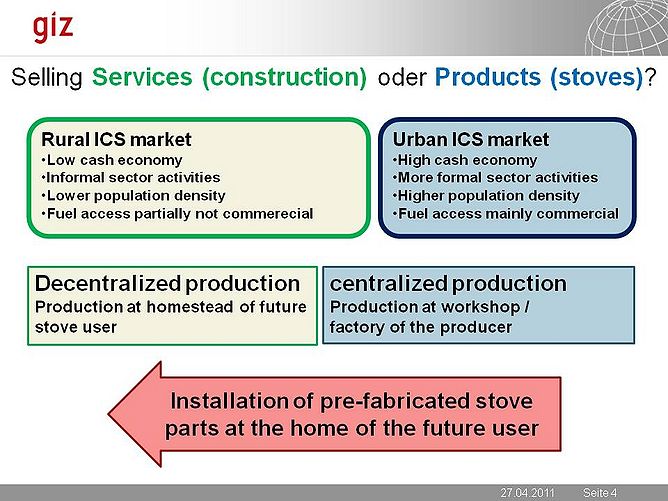

The links between technology selection and design of the intervention

Selecting a stove technology is much more than just a technical decision. It has huge impacts on the overall design of the intervention. One of the chore questions is related to the portability of the stove. In generalizing terms, one could distinguish between the needs of the rural and urban ICS markets as below. There are, however, also a number of examples of rural areas with portable stoves. This holds particularly true in areas where cooking is done outside. Hence this is just a generalization to demonstrate the links between technology selection and the design of the intervention. It does not cover all cases.

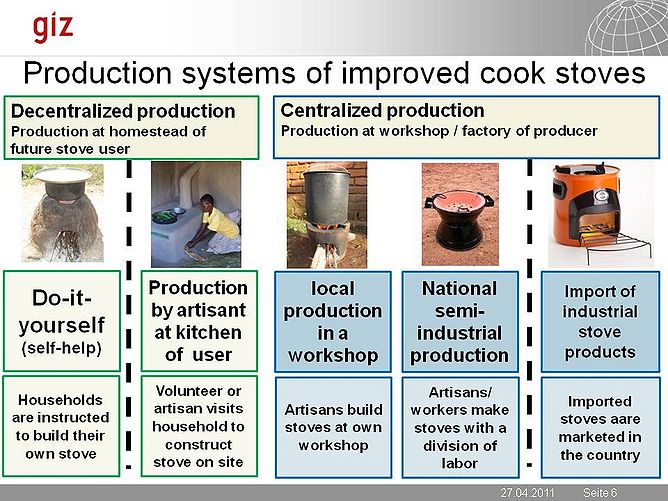

As manifold as the types of stoves available, there are also different modes of stove production to be distinguished.

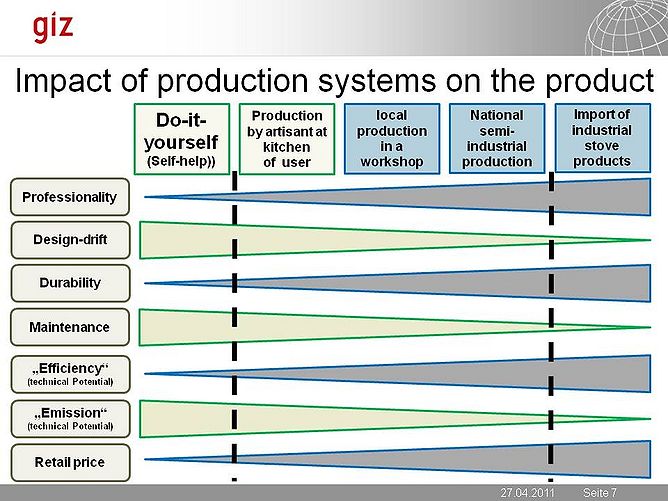

In most of our interventions, we focus on the three options in the center of this slide. Self-help “do-it-yourself” stoves tend to be of very low quality (sometime even worse than the baseline stove) due to the low skill level/lack of practice in stove construction. The option of imported industrial stoves is a rather new development which has not been tried yet at large scale in GIZ stove interventions.

More specialized producers (e.g. in the semi- or industrial production) have more routine in the production of ICS. Combined with tooling and quality control mechanisms, the stoves will have less cases of design drift as compared to fixed stoves being built from scratch at the customer’s house. (Semi-)Industrial stoves commonly are made out of metal. As the manufacturing is done according to defined standards, the (semi-) industrial stoves tend to be more durable as the locally build stoves out of mud, bricks or cement. Hence the latter require more attention in terms of maintenance. Standardized production allows for the observation of important dimensions and principles. Therefore, the (semi-) industrial stoves often provide higher technical potentials for “efficiency” (reduced specific consumption) and for reduced emissions. The actual realization of these potentials is dependent on the user behavior. While many technical aspects favor the standardized, centralized production, the retail costs of these stoves are often higher as compared to their local competition because of cheaper materials, informal price setting and lower transportation costs.

There are new trends to “cross the borders” of these categories:

- Industrial pre-manufactured stove components used in local fixed-stove construction;

- Industrial flat-pack assembly kits imported for in-country assembly and sales.

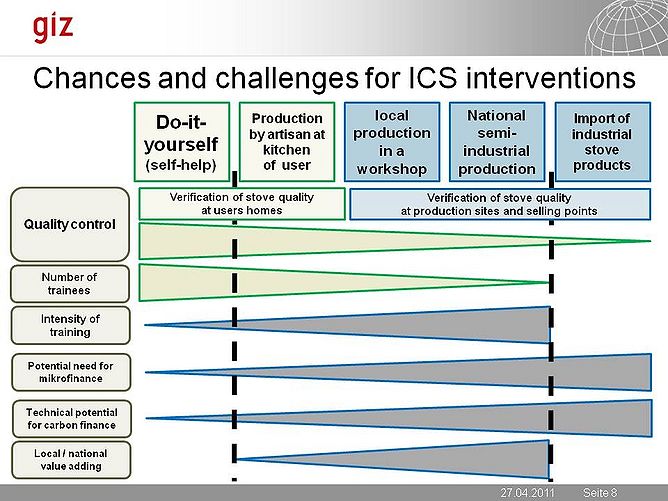

The different production systems provide different chances and challenges for the implementing organization. Decentralized production requires verifying the quality of the stoves at the site of construction at the homes of the users. This is a huge effort as compared to visiting the production or selling points of portable stoves.

While specialized workers in the (semi-)industrial production potentially require a more intense training, the decentralized production systems tend to have lower numbers of stoves produced per producer per year. For the same annual production, far more producers have to be trained and supervised as compared to the centralized production.

(Semi-)industrial stoves tend to be more expensive than locally produced stoves in a rural environment. Hence the potential needs for microfinance to lower the investment barrier tend to be higher for the more expensive products. Another reason is that - depending on the country – microfinance tends to be found more frequently in urban as compared to rural settings. On the other hand, rural households have lower cash incomes which increase the need for assistance if investments are required.

More efficient stoves have a higher carbon saving as compared to less efficient stoves if compared with the same baseline stove. This applies even more if the more efficient stove has been manufactured in a standardized manner as the technical potential for savings can easily be assessed. Locally build fixed stoves can be all different in their individual performance as for example a small variations of the air inlet of the chimney may either result into too much draft (reducing the efficiency) or too little draft (smoke in the kitchen). The monitoring for the carbon saving verification in the field would require much more effort.

Planning of ICS interventions

The planning of interventions to enhance the production of ICS should not be done in isolation. The production is part of an overarching value chain which starts with the access to the required inputs and comprises all the steps including the distribution, sale and utilization of the stoves.

There is no benefit in training future producers on stove production, if…

- They cannot access the inputs;

- They have no access to markets;

- If the product does not sell;

- If the product is not used.

| ►Inputs | ►Production | ►Distribution | ►Sales | ►Utilisation |

On each of these steps in the value chain, observations can be made on the micro, meso and macro level:

- Micro level: e.g. suppliers, producers, traders, users

- Meso level: e.g. service providers, research stations, transportation systems…

- Makro level: e.g. Governments, international companies, donors…

For each of the levels, it is worthwhile to identify the relevant actors, important influencing factors, opportunities and threats etc. which can or will take influence on the building-up of a commercial supply-demand system for ICS.

Based on this analysis, important activities can identified which should be considered in the detailed planning of the intervention.

Example for value chain analysis: e.g. Kenya???

Planning of activities to enhance ICS production

Once the market niche has been identified in the planning process, plans have to be developed how the supply-system of ICS can be established. If it is a new product to the country, this will require to be done in phases of different relationship between the implementing organization (short: the “project”), the producer and the customers of ICS.

Prototypes of new stoves are produced in a lab-controlled environment. There is close collaboration between craftsmen, researcher and stove users. Once the prototype fulfills the required standards, it will be field tested at a larger scale to verify if the stove performs well enough if ordinary households are using it. In reality, there might be alterations between phases if lab testing and field testing. In this period, production is controlled by the project. Market forces do not yet play a role.

Once the field test confirms the satisfaction of the target group with the product, a market based production system will be established for a specific area. In the initial stages, some support to the producers might be required to buffer their risk in production, but there are some lessons from to be shared:

- Do not pay artisans for attending a training workshop on stove production (at least their time should be their contribution into a better future). Good experiences have been made by

- Do not provide free tooling and free inputs to kick-start production (it may attract the wrong artisans who are just there for the inputs and do with them other work). There can be soft loans or cost sharing arrangements which could be performance based.

Piloting ICS Production

The initial step from “prototyping” to “piloting production” is very crucial and difficult.

On the one hand...

- we are not yet sure of the product (teething problems);

- we are not yet sure of the market (new product);

- we are not yet sure of the market case (production costs vs. sales price);

- we are not yet sure of the marketing system.

Because of these uncertainties, there is a (felt) need to protect the initial producers against the risks of entering this new production business. This “protection” can take the form of…

- providing producers required tools;

- providing producers required production materials;

- providing producers grants or loans;

- giving producers large production contracts (= project buys all the stoves of them);

- employ the producers (=time-based contracts);

While these interventions are useful to get the production going, there are also huge risks for the long term sustainability attached to these approaches.

- The initial producers may consider themselves as “employees of the program” and therefore the program will have to provide a market for the stove/ has to market the stoves for them;

- These “special conditions” for the early producers cannot be maintained on the long run, if sustainable supply-demand systems are the envisaged goal of the intervention. Hence producers who will be trained later will not benefit in the same way as the initial producers. But the knowledge about the initial conditions will spread fast, leading to constant battles with jealousy between old and new producers and demands for support by the “disadvantaged” producers

- If the risk to produce for the market is buffered by the project, there is little motivation for the producers to develop a cost-efficient production concept. The initial price for the stove will always be high as there is no incentive to produce many stoves in short time. As a remedy, projects tend to subsidies the initial price for the customer to still find a market for the stove. Once this system of a workshop-gate on the side of the producers and a project-based subsidized customer price is established, it will be highly difficult to exit this scenario without severe fractions. If the stove price goes up until it reaches the real price, the customers will complain that they are used to have a cheaper stove. Or the workshop-gate price is pushed lower, than the producers may lose interest. Unless there is a clear element of “economy of scale” which will result in a “natural reduction of production costs over a short time”, there is no easy exit of this system.

It is therefore crucial to plan the initial production already with the vision on how this system can be scaled-up into a market based, sustainable supply-demand system. Already the selection of the initial producers and the way of cooperation will impact on the long term performance of the sector.

In many countries, there are artisans who worked already with former “stove projects”. New interventions often have also to combat expectations which are generated from these past experiences. It requires time, good knowledge of the local stove project history and strong standing to establish a different system. The selection of the location and the initial producers is something which should be done based on thorough planning.

It is not possible to suggest “the best way” on how to initiate the ICS production as it is highly circumstantial. However, here are some ideas which have worked in the past:

- At the end of the prototype-development phase, a market test with test-sales (what would people pay for the stove?) can be implemented and orders for stoves could be generated.

- Based on this concrete demand, artisans with an already established workshop and business can be asked if they are interested to satisfy this documented demand if trained by the program. It is assumed that these producers have all tools and labor required to manufacture the stoves. The project may give a warranty that the investment into the materials for the stoves will be covered in case the stoves actually are not sold despite the orders of the customers as sometimes there are defaulters amongst the test-sale participants.

- Once these first stoves are produced and sold, the initial producers are invited to participate in awareness and marketing activities to establish their own links to potential target groups and understand how to find markets for their new product.

- They are continuously supported through quality control and additional awareness campaigns. Feedback rounds with early customers may assist to create a better understanding of the perception of the customers.

Scaling-up of ICS production capacities

Once an initial ICS production is established and the market case has been proven, there is need to scale-up the production to satisfy larger customer groups.

Scaling-up can be done in two dimensions:

1. Increasing the number of small scale supply-demand systems

2. Increasing productivity of production systems

In the first case, the concept of “local production for local markets (based on local resources and local skills)” is maintained. It is a concept which provides a close link between producers and users and is relatively robust against external shocks. This form of scaling-up requires a large effort in capacity building for many artisans. There are good examples for this approach: the “training of trainers” concept in Uganda and the “mainstreaming concept” in Malawi.

In the second case, the production system as such is transformed to increase the productivity per producer. This can be based on the introduction of improved tooling (e.g. in Senegal) of local artisans or the establishment of semi-industrial production centers (e.g. in Ethiopia).

[habe wir hier Dokumente zum verlinken?]

It is important to consider the coordinated growth of both production and demand, as demand without products is frustrating the customers and production without markets ruins the producers.