Barriers and Risks to Renewable Energy Financing

► Back to Financing & Funding Portal

Overview

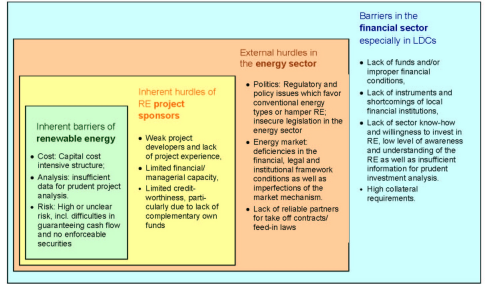

There are a number of key risks and barriers that can threaten investment in renewable energy (RE) projects and thus prevent the uptake of desirable technologies.

Lindlein & Mostert (2005)[1] have suggested that it is appropriate to group these barriers by the market categories supply, demand and framework conditions. From this view the most pervasive barriers to financing renewable energy from demand to supply are categorised as:

- Demand side barriers due to the characteristics of RE projects and internal problems of RE project sponsors.

- On thesupply side of RE finance there are several shortcomings in the financial sector especially in developing countries where there might be no supply at all.

- Framework conditions for projects within the energy sector can include substantial burden and barriers for RE finance[1].

At a broad macro-economic level, barriers to RE investment can be categorised as follows[2]:

- Cognitive Barriers. Theses relate to the low level of awareness, understanding and attention afforded to RE financing and risk management instruments particularly in low income countries.

- Political Barriers. These are associated with regulatory and policy issues and governmental leadership.

- Analytical Barriers: these relate to the quality and availability of information necessary for prudent underwriting, developing quantitative analytical methodologies for risk management instruments and creating useful pricing models for environmental markets such as carbon emissions permits.

- Market Barriers: these are associated with lack of financial, legal and institutional frameworks to support the uptake of RE projects in different jurisdictions.

Technological Differences

Different RE technologies have different degrees of exposure to the various barriers and risks due to their specifics and maturity.

The table below highlights some of the key risk issues affecting different RE technologies. Technology and operational risks are the principal deterrents to attracting appropriate commercial insurance cover[2].

Key Risks & Barriers Associated with RE Projects | ||

RET Type |

Key Risk Issues |

Risk Management Considerations |

|

Geothermal

|

|

|

|

Large PV

|

|

|

|

Solar thermal

|

|

|

|

Small hydropower

|

|

|

|

Wind power

|

|

|

|

Biomass power

|

|

|

|

Biogas power

|

|

|

|

Tidal/wave power |

|

|

|

Notes: * The probability of success in achieving (economically acceptable) minimum levels in thermal water production (minimum flow rates) and reservoir temperatures. **Stimulation technology attempts to improve natural productivity or to recover lost productivity from geothermal wells through various techniques including chemical and explosive stimulation. | ||

Source:[2]

Generally all large RET projects will require access to long term funding on a project finance basis, but their exposure to their barriers and risks will differ. Thus the need to obtain pre-investment financing and other project development processes will be more significant for hydro projects and less so for other technologies that do not have the same impacts on land use and on downstream communities[3].

Thus project sizes and transaction cost barriers are generally lower for wind and geothermal projects that can be developed on a greater scale than other technologies.

Geothermal and small hydro can be competitive with conventional technologies, and wind energy is also approaching competitiveness in some countries. However, solar technologies remain a long way from achieving cost competitiveness; therefore its affordability remains a key risk[3].

Resource uncertainties are also a problem for all technologies, though in differing ways:

- Geothermal projects have the greatest risk at the time of resource appraisal, when the expensive drilling of exploratory wells is needed.

- Biomass projects have a significant problem with the continuing availability of affordable and adequate resources.

- Technologies dependent on carbon financing are likely to be more vulnerable to the resource uncertainty problem.

Off-Grid Projects:

- These projects face different problems from those on non-grid RET projects. Off-grid projects are generally reliant on sales of individual household or small scale systems to rural communities. Technical challenges may be limited but affordability and financeability are key.

- The very small scale of such projects, down to the individual household level, means transaction costs can become an overwhelming barrier.

- The lack of long term project financing is less of a barrier to such projects, due to their very small size, they typically rely on corporate finance or on customer purchases[3].

The figure below shows the significance of barriers and risks to different technologies, providing an indication of which barriers and risk are likely to pose the greatest challenges to developing RETs.

| Technologies & Barriers and Risks | |||||||||||

|

|

Financing Barriers |

Project Risks | |||||||||

|

|

Lack of Long-term Financing |

Lack of Project Financing |

High & Uncertain Project Development Costs |

Lack of Equity Finance |

Small Scale of Projects |

High Financial Cost |

High Exposure to Regulatory Risk |

Uncertainty Over Carbon Financing |

High Costs of Resource Assessments |

Uncertainty over Resource Adequacy | |

|

On-Grid |

| ||||||||||

|

Wind |

Hi |

Med |

Lo |

Lo |

Lo |

Med |

Med |

Med |

Lo |

Med | |

|

Solar |

Hi |

Med |

Lo |

Med |

Med |

Hi |

Med |

Med |

Lo |

Med | |

|

Small Hydro |

Hi |

Med |

Med |

Med |

Lo |

Lo |

Med |

Lo |

Med |

Hi | |

|

Biomass |

Hi |

Med |

Lo |

Lo |

Med |

Med |

Med |

Med |

Lo |

Hi | |

|

Geothermal |

Med |

Med |

Hi |

Med |

Lo |

Lo |

Med |

Lo |

Hi |

Med | |

|

Off-grid |

| ||||||||||

|

Solar/Micro-hydro |

Med |

Lo |

Med |

Hi |

Hi |

Med |

Lo |

Lo |

Lo |

Med | |

|

Source: Adapted from The World Bank, 2013. Financing Renewable Energy - Options for Developing Financing Instruments Using Public Funds[3]. Note – Lo = Small/no impact (mitigation of risks is desirable.) Med = Moderate impact (mitigation of risks is less likely to be required.) Hi = Significant impact (mitigation of risks is generally necessary if the project is to proceed. | |||||||||||

Financing Barriers

Lack of Long-Term Financing

RE technologies tend to have high up-front costs and low

ongoing operating costs, making access to long term funding for such projects a necessity. Without long-term financing, investment decisions are biased toward conventional technologies that can befinancially viable with shorter-term loans. In many developing countries long-term financing is difficult and sometimes impossible to get. This is in part due to regulatory or other restrictions on long-term bank lending. A lack of experience with RE technologies also means that potential financiers may feel unable to assess the risks involved, and there may also be a lack of matching funding sources.

Long-term financing also depends on investors who are looking for long-term assets to match the profile of their liabilities such as pension funds. In developing countries, such funds either don’t exist or limit investment activities largely to the purchase of government debt owing to its low risk[3].

Lack of Project Financing

RE technology projects also seek to access funds on a project finance basis. With project finance the security for the loan comes from future project cashflows and little/no up-front collateral is required. There is still however, the need for a share of the project to be funded from equity. This type of funding allows RE technology projects to spread their costs over the project lifetime, funding the high-upf ront cost fro the positive cahsflows generated during operations. The alternative to this would be to rely heavily on equity funding, payments to which can be delayed until the later years of the project [4].

RE technologies are more exposed to the limited availability of project financing than most conventional technologies as the share of capital costs in their total cost is much greater[3].

High and Uncertain Project Development Costs

RE technologies projects are quite vulnerable to changes in the regulatory framework. Due to their lack of cost competitiveness, these projects are dependent on a supportive regulatory framework to proceed—including commitments to pay premium prices, priority access to electricity grids including support for the necessary infrastructure investments and guarantees of purchases of their output. Severe problems for project viability can arise where the regulatory framework changes[4].

Furthermore, such projects are often located in enevironmentally and socially sensitive areas. For example with larger solar and wind projects, land use requirements can be very significant. All theses factors make it necessary for RE project sponsors to have access to significant amounts of funds to cover the costs of project development prior to reaching financial close. Generally such funds come from their own resources orf rom sources of risk capital. In developieng countries the small size of potential RE technology project sponsors means that this route of funding is limited. Generally there is little availabilty of risk capital in developing countries financial markets [3].

Lack of Equity Finance

While large numbers of renewable energy technologies (RETs) project developers exist, there are only limited numbers of large-scale project sponsors, particularly among those operating in low-income countries, with the ability and willingness to fund RET projects on a corporate finance basis. RET projects are generally smaller than conventional generation projects and this is reflected in the size of developers. The high risks of investment in many LICs, whether inside or outside the energy sector, will also tend to deter many larger energy companies based in more developed economies leading to a lack of equity[4].

This lack of equity capital means that project sponsors are often unable to cover the costs of development activities without external assistance. But, as highlighted above, access to risk capital of the type required is limited in LICs. The lack of equity capital also increases the dependence on project financing, as sponsors are unable to provide collateral for loans or to put up large amounts of equity. As a result, loans have to be secured against future cash flows, given the absence of alternatives[3].

Small Scale of Projects

The small scale of many RET projects creates significant problems in obtaining private financing. Economies of scale in due diligence are significant, and many larger financial institutions will be unwilling to consider small projects. Typical due diligence costs for larger projects can be in the range of $0.5 million to $1 million. International commercial banks are generally not interested in projects below $10 million, while projects up to $20 million will find it difficult to obtain interest.4 But lower limits may apply for domestic and regional banks operating in smaller economies, particularly where these lack the resources themselves to make large-scale loans[5].

While household, micro, and mini systems are obviously far below these limits, even larger grid-connected RET projects are generally smaller than their conventional counterparts. As a result, they often struggle to attract funding from larger financiers. These very small systems also face the problem of lack of local demand in rural areas, leading to underutilized assets and worsening financial returns and attractiveness to financiers[3].

Risks of Renewable Energy Projects

High costs of resource assessments

Resource uncertainties are a problem for all technologies but in differing ways. For geothermal projects, the greatest risk comes at the time of resource appraisal when expensive drilling of exploratory wells is needed.

High exposure to regulatory risks

While all energy projects face regulatory risk, RET projects are particularly vulnerable to changes in the regulatory framework. Their lack of cost competitiveness means that these projects are generally dependent on a supportive regulatory framework to proceed—including commitments to pay premium prices, priority access to electricity grids including support for the necessary infrastructure investments, and guarantees of purchases of their output. Severe problems for project viability can arise where the regulatory framework changes.

High financial cost relative to other technologies

The high costs of RETs relative to conventional generation technologies are a key risk to their success. These higher costs are exacerbated by the high cost of funds in many underdeveloped financial markets (for example, borrowing costs as high as 16–18 percent have been quoted for Nepal and among other SREP pilot countries, lending rates of 16.5 percent and 15.1 percent have been reported by the International Monetary Fund [IMF] for Ethiopia and Honduras). The high up-front capital costs of many RETs compared to conventional technologies further worsen their commercial position and make costs a concern.

For grid-connected projects, the high cost of RETs can be overcome, at least in part, through priority rights to dispatch and/or must-take obligations on off-takers. This means that these projects are effectively removed from having to compete for dispatch with other lower-cost conventional technologies. The higher costs imposed on off-takers of purchases from RET projects are generally recovered from electricity customers as a whole—either through the monopoly power of the off-taker or, where the electricity market is competitive, through some form of levy or universal charge.

But if costs are too high relative to alternatives, affordability concerns may mean that such priority treatment is not given. There may also be concerns whether RET projects that are more expensive than conventional alternatives will have commitments to pay them honored, whether governments will continue to make the necessary funds available to cover the obligations of publicly owned off-takers, or whether attempts will be made to renegotiate these commitments on the grounds of affordability.

Off-grid RET projects are more likely to be competing directly with conventional technologies, such as diesel generation. For these projects, if users are given a choice of technology, RETs are unlikely to be selected unless their costs can be brought down to competitive levels. This is happening more as global oil prices rise. For example, the cost of solar photovoltaic (PV) modules fell by over 50 percent between 2008 and 2010. In remote locations and small loads, this can make solar PV supplies competitive with diesel generation.

High operational risk

The high costs of renewable energy technologies (RETs) relative to conventional generation technologies pose as a risk to the success of RETs.

Uncertainties over resource adequacy

Without high-quality assessments of renewable energy (RE) resources, the risks of RE projects are greatly magnified, and private financing will be correspondingly harder to obtain. Resource assessments for wind, hydro, and biomass in particular need to be available on a site-specific basis (that is, general assessments such as wind atlases are not sufficient for project financing) and for an extended period (at least one year of reliable and auditable data, for example). Even then, the risk remains that output—and therefore cash flows—will be less than expected, whether due to lack of rain or wind.

For solar projects, the problems are somewhat different. There are extensive databases available on solar resources worldwide; whether conditions are adequate for PV technology can be estimated with a fair level of certainty. The situation is rather different for the use of concentrating solar power (CSP), which is only suitable in a limited number of locations and where careful investigation of resources continues to be required. But CSP remains a much more immature technology, and therefore may not be suitable for most LICs or at least for the transformative purposes envisaged by this paper.

Geothermal projects face a particular risk in that the assessment of resources involves the drilling of expensive exploratory test wells, which may not succeed in finding adequate resources. The costs of these wells are high and the combination of this high cost and risk of failure may deter exploration of geothermal resources in the first place. As a result, while many countries claim that they have significant geothermal recourses, very little potential has been developed so far. Even where an exploration program is successfully completed, there are continued risks of resource adequacy from the failure of production drilling wells and the degradation of the geothermal reservoir over time.

Uncertainties over Carbon Financing

The sale of Certified Emissions Reductions (CERs) through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is a widely recognized source of revenue for RET projects in LICs, and one that can help reduce their costs relative to conventional technologies (in effect acting as a form of subsidy). But unless some way can be found to mobilize this potential revenue source up front, it is unlikely to help at the time of project development and implementation.

There are significant uncertainties over the timing and amounts of revenues from the sale of CERs. The process for registration of projects is long and the outcome uncertain, particularly if a new methodology is involved. Prices can also be volatile. The main benchmark price is that set under the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which collapsed to almost zero during 2008. Finally, there is the uncertainty over the CDM post-2012 created by the lack of a replacement for the Kyoto Protocol, which forms the basis for the mechanism.

Specific Answers to Observed Barriers

Solar Home Systems - Tansania & Rwanda

Mobisol tries to close the financing gap by getting loans and financing as a big company and then collect the money from costumers on long term in small rates by M-PESA.[6]

Further Information

- Risks in Energy Access Projects - This article includes an example of activities to be carried out during a project’s preparation to reduce the occurrence of risks or their influence at any point in a project’s life. It also contains an extensive list of risks (technological, institutional, geo-political, financial/economic, social and environmental) and suggestions on how to minimize, mitigate or control these risks during the life cycle of a project. In addition there is a brief explanation of risk management and how to prioritize risks. The last section leads to experiences applying de-risking approaches for rural electrification and further reading.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lindlein, P. & Mostert, W., 2005. Financing Renewable Energies - Instruments, Strategies, Practice Approaches, KfW.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2004. Financial Risk Management Instruments for Renewable Energy Projects - Summary Document, UNEP, Division of Technology, Industry and Economics.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 The World Bank, 2013. Financing Renewable Energy - Options for Developing Financing Instruments Using Public Funds.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Renewable Energy Financial Instrument Tool (REFINe). Available at: http://www-esd.worldbank.org/refine/index.cfm

- ↑ Scaling-up Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Finance and investment perspectives, K Hamilton (April 2010). Chatham House: Energy, Environment & Resource Governance Program Paper 02/10. (http://www.chathamhouse.org.uk/research/eedp/papers/view/-/id/874/).

- ↑ Mobisol explanation: http://www.plugintheworld.com/mobisol/product/ , visited 2015/11/05