Energizing Microfinance Workshop Documentation

Summary of the practitioners’ workshop

held in Berlin on April 6, 2011.

To support the development of projects that interlink energy provision and microfinance, the meeting brought together selected experts and practitioners and allowed them to share experiences, discuss lessons learned and define crucial framework conditions in a closed session.

Background

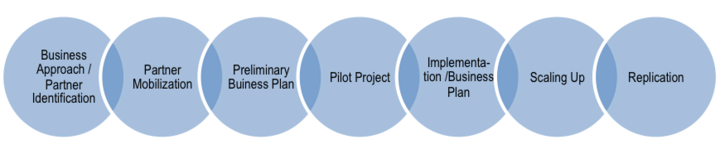

The organizations that took part in the workshop came with varied experiences in the development of energy loan projects. To build a common ground for the moderated discussion, a typical project lifecycle was chosen, starting at the point of partner identification and mobilization, going through the preliminary business plan, the pilot and implementation phase and ending with project scale-up and replication procedures.

Figure 1 Typical Project Cycle

Applied approaches, common challenges and recommendations from the field have been collected for various stages of the project lifecycle. Carbon finance has been a popular topic lately as a potential matching tool for such projects, and therefore a score of issues as well as opportunities associated with carbon-offset strategies were specifically addressed. As the gathering was also a preparatory working group for the adjacent conference “International Conference on Micro Perspectives for Decentralized Energy Supply“, a primary aim was to identify crucial research gaps and the role that research and education could play in developing solutions.

A synthesis of the workshop results is described below. The complete minutes of the meeting can be made available upon request.

Key Insights

Partner Identification

To begin, the business approach needs to be defined. The project origin can be a non-governmental or governmental proposal, a contract with a microfinance institution (MFI) or a collaboration with funding partners. The first activity is to identify project partners: technology and service providers, local academic networks, funders and MFIs. The discussion revealed that a standard selection process is seldom applied – eventhough rating systems already exist in the microfinance sector, decision criteria depends heavily on the local setting. Of paramount importance for collaboration with an MFI is firstly the commitment of the upper management and secondly a so-called “internal champion”, a close working partner within the institution that strongly supports the project.

| Partner Identification – Project Examples 1) Bottom up: SIDI in Senegal

2) Top down: Microenergy International (MEI) in Peru

3) "Go with the flow": Planet Finance in China

|

One proposition was to think more broadly in terms of end-user financing and consider farmer unions, savings and credit cooperatives (SACCOs), energy enterprises or local businesses as financial intermediaries as well.

When it comes to the technical planning and implementation of energy loan projects, finding the right technical provider was agreed to be the most difficult challenge. Technology companies can be found in almost every country, but the majority maintain their offices in big cities and are not willing to service rural areas. In Senegal for example, SIDI had to create their own company to get the products to the customer as all solar retailers reside in Dakar.

Concerning the inclusion of carbon finance into the project lifecycle strategy, the highest upfront barrier proves to be the initial cost. While it is possible to obtain refunded credits for up to 2 years, the refund period starts at the moment the project is officially listed as a carbon offset venture with the mutual consent of all stakeholders. The Swiss NGO myclimate claims that carbon money can facilitate a number of objectives – improved infrastructure on a long-term basis, project-based technology transfer and increased efficiency. For this reason, carbon finance tends to attract a lot of interested partners, but not necessarily partners with expertise. It remains difficult to identify someone who can assure the necessary monitoring process for the entire project duration.

Another hurdle is the requirement of additionality - in order to be eligible for carbon credits, it must be proven that project implementation would not be possible without carbon finance. Two justifications were identified during the discussion: the first argument is to state that a scale-up would only be possible with the support of continous carbon finance, and the second is to be able to extend the project to even more impoverished target groups, a justification that works especially well for MFIs committed to poverty reduction.

Partner Mobilization & Preliminary Business Plan

After the project has been initiated, it is vitally important to mobilize the selected partners, including building a relationship and organizing communication channels. A timeline has to be set and an assessment of the institutional capacity conducted. The main activity for the preliminary business plan is the field research, which needs to be prepared, carried out and evaluated together with the partner organizations. This field research should lead to a first selection of energy products for the pilot project and allow for stakeholder contracting.

A critical question is how to design the ideal contract between a financing institution and a technical supplier. For many MFIs it is the first time that they have had to deal with hardware products, and their fears regarding product quality, supplier trust and commitment have to be taken seriously. Questions that came up during the meeting included: what if the supplier is only willing to deliver in larger quantities? Is the MFI able to handle hardware product stocks? Does the legal setting allow the MFI to receive a commission from the product provider?

Another crucial decision during the first phase is whether to procure products from local manufacturers and support the target region further or to import products with more reliable quality.

One important objection concerning the technical design: if carbon finance is a goal from the beginning, will the search for appropriate products be biased towards technologies that offset the highest amount of CO2 emissions, or is it possible to remain technology neutral during research? In some cases, LPG or diesel generators may be more economically viable and closer to the needs of end-users, but they might not be acceptable to the growing number of carbon-driven funds.

The experts agreed that most MFIs need incentives to take on an energy project. Small financial incentives may suffice as risk capital insurance for experimentation and innovation, and to have funds in place for stock, marketing and training. To encourage MFI mobilization, it was recommended to invite decision makers to nearby villages where some of the proposed products have already been applied and can serve as successful examples. Another method could be to inform the MFI of other partners that would be more willing to work with them, e.g. internationally renowned funding sources such as the European Union.

Examples from Bangladesh and Nepal have shown that subsidy schemes for service and maintenance increase the sustainability of a project immensely, especially if rural areas are targeted. The inclusion of carbon finance into the business case at an early stage offers a regular cash flow once the project enters a mature stage. Worries about the discontinuation of the CDM methodology after the year 2012 were dispelled by myclimate, which sees an evolving demand for carbon offsetting in the voluntary market.

Pilot Phase & Implementation

Once the initial business plan has been developed, it should be pilot tested. Selected products and the monitoring procedure are validated, the credit design needs to be checked and logistics are subject to optimization. In the final elaboration, the sales forecast has to be reviewed and payment rates, technological and other decisions should be revised as appopriate. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the MFI's upper management to validate the business plan.

A typical challenge in this case is that a lot of projects remain in an "internal pilot phase" for a long time, where the business model is constantly changing in terms of loan as well as energy product design. It is therefore crucial to identify indicators that signal the end of the pilot project and the start-up of actual implementation. Two approaches under discussion were: "small is beautiful" where the number of variations are kept small to get thourough test results in a timely manner, or "make sure to find out what is needed", if end-user needs are perceived to be exceedingly unclear in the beginning.

Many energy products come with a high upfront cost, a major challenge for most of the rural population. Subsidies are proposed as a method to bring this cost down. However, in order to avoid market distortions, it was specifically recommended to use subsidies to reduce the cost of the product itself only if this will anticipate and agree with the real price of the product at a later stage of dissemination.

However, experience reveal that the high upfront costs of appropriate energy products are only a part of the financing problem. The development and entertainment of service infrastructure is a cost factor which is often neglacted and under-estimated. Directing subsidies in this field might be a more sustainable solution on the longer term.

A new problem for the MFI integrating an energy portfolio is the need for additional end-user training in this field. Participatory training methods proved to be more appropriate in order to encourage participants to ask questions. Experiences from Kenya have shown that an internal "energy department" within the MFI is very useful to build capacities of such additional activities, in order to identify and solve potential problems before they arise.<span style="color: rgb(255, 0, 0);" />

Lastly, microfinanced energy projects are complex and always involve several stakeholders. To avoid too much conflicts, it is worth to elaborate detailed and clear Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) and to rediscuss the different roles and responsibilities in regular intervals.

Scaling Up & Replication

The long-term goal of a project is to implement the business plan successfully and expand both clientele and product range. Replication strategies may include new MFIs partners, new regions or even new countries to apply the business case.

Unfortunately, it is not easy to apply small scale methods to large scale applications. Experience from Uganda has shown that a big problem arises once the MFI and the supplier do not grow at a similar rate. It was discussed whether this is the reason why one-handed models, in which both the technical and the financial activities remain under one umbrella (e.g. Grameen Shakti in Bangladesh), provide the only real success stories so far. Another approach is to de-skill the technical process at the last mile as much as possible to enable collaboration with regular technicians present in the area.

While some argued that it is the "human factor" in a project which makes it so hard to scale up, the practitioners agreed that lessons learned, especially about things that went wrong, are useful for other projects, eventhough their conditions might be different.

A good example for a decentralized up-scale was the "innovations unit" at SELCO India, which searches for smart energy entrepreneurs and supports them through the provision of proper tools, skills and working capital.

Scaling up and replication phases promise the most benefits for utilizing carbon finance. Projects can be bundled under a so-called Programme of Activities (PoA) and then replicated and getting funding for as long as 28 years.

Conclusion

The workshop uncovered a number of common points the group of expert practitioners agreed on as well as a couple points of contention. If the goal is a reliable provision of energy, it is crucial to create businesses that are sustainable in the long run. To be successful, continous monitoring processes and a thorough assessment of end-user needs is crucial from the beginning. Furthermore, standardization has shown to make things easier for various projects.

Concerning the application of carbon finance, some workshop participants fear a technological objective shift towards products that offset CO2. Also, the long project duration that comes with the inclusion of carbon credit schemes can make it difficult for partners to pull out of the venture if desired.

Strong synergies between carbon finance and microfinance are seen in the following activities:

- Financing different project phases - carbon finance really kicks in after the pilote phase when projects scale up and infrastructure costs become relevant in order to replicate.

- Monitoring - regular collection of payments and their monitoring through MFIs has strong synergies with the monitoring requirements of carbon finance programs. This monitoring can even be financed by carbon credits.

- Standardization - The microfinance industry and the carbon finance industry both require a high level of standardization in order to scale up. This bears further synergies of combining these approaches.

- Additionality of carbon $$ - In order to become eligible for carbon finance, projects generally have to prove that they use the money for activities which would not be profitable without these funds. This is often the case if service and maintenance activities have to be extended to rural areas as well as extentions of the program in order to reach down the poverty line.

It remains a challenge to develop a good project design that satisfies both the needs of microfinance and of carbon finance. One other carbon finance question still remains open: who is the best focal point for carbon finance - is it the microfinance institution, the project developer, the energy product provider or a joint venture set up between all stakeholders? It will be on future project developers to find the best solution.

(Pictures of the meeting have been made available online: http://flic.kr/s/aHsjufd4vB)