Gender Mainstreaming in Energy - Need

Gender Mainstreaming in Mini-grid

According to the United Nations Economic and Social Council gender mainstreaming is defined as “a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design,implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated”[1].

Need for Gender Mainstreaming in Energy

Men and women access and use energy for different purposes and therefore lack of it also affects them differently[2]. This is because access to and use of energy is determined by differnet factors such as their gender roles in the society, the kind of work they do and the resources they have access to.

Understanding these gendered use/impacts of energy helps in designing sustainable energy solutions that benefit both men and women equally. Gender mainstreaming also acknowledges women’s contribution and involves them in all stages of the reneweable system design. It also helps to limit any negative impact that could occur due to the gender blind planning process and policies[3].

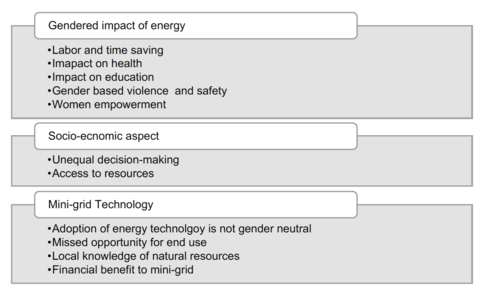

Figure 3 summarizes why gender mainstreaming is important in energy (especially for mini-grids)

Gendered Impact of Energy

Access to or lack of sustainable energy has the following gendered impact on women’s lives:

Labor and Time Saving

In developing countries, women and girls are mostly responsible for collecting communal resources such as firewood, water and fodder for animals. They spend about 2-20 hours per week or even more on collecting firewood and carrying it over long distances[4]. This limits the time they could have spent on other productive or leisure activities[5][6]. Furthermore, climate change impacts such as deforestation, desertification and ecosystem imbalance have worsened the situation as women now have to travel far off to collect communal resources that were previously nearby available [7].

Women in rural areas are also involved in subsistence farming and this is often labor intensive and time-consuming[6][2]. When activities such as pumping water for irrigation, grinding grains or oil pressing can be mechanized, it greatly reduces the drudgery for the women[2].

Impact on Health

In rural areas, women are the ones responsible for cooking. They use traditional fuels such as firewood, cow-dung and other biomass for cooking. Traditional cook stoves such as the three-stone fire are mostly used for cooking. These cookstoves are highly inefficient and release toxic air pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide and benzene. Since the kitchens are also poorly ventilated, women are then exposed to indoor air pollution. 2 million people worldwide, mostly women and children die each year from indoor air pollution[5][2]. The use of traditional fuels such as kerosene lamps and candles for lighting also result in fire burn and indoor air pollution[8].

As mentioned above, women have to collect and carry firewood over a long distance. Across African countries, IEA estimates that women carry fuel loads that weigh from25 to 50 kg [9]. It is physically challenging to carry such heavy loads and result in health problems such as backache and miscarriages[10][2]. Solutions such as electric cooking could provide clean alternative to traditional fuels and reduce the burden on women.

Access to electricity in hospitals is another crucial need. More than 60% of health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa do not have access to electricity and over 70% of medical devices in developing countries fail due to unreliable power supply[11]. In poor energy situations, the medical staffs also refer to flashlights or kerosene lamps for lighting. This increases the risk of giving birth at night and also affects the neo-natal care of the babies. Hence, access to reliable electricity for health centers could greatly improve healthcare facilities for both men and women[12].

Impact on Education

Girls are usually responsible for helping their mothers collect firewood and in other labor-intensive work such as grinding grains or pumping water. Access to electricity results in time saving and thus frees up time which can be spent on education. Also lighting at night extends the studying hours in the evening.

A study in Vietnam found out that in the newly electrified households, electrification resulted in an increase in enrollment rate for both boys and girl but it was not clear if electrification had a greater impact on girls as compared to boys[13].

Gender Based Violence (GBV) and Safety

Women and girls usually have to travel to far-off distance for collecting firewood and other communal resources. Hence, they can become victims of gender-based violence or get bitten by other insects or snakes along the way or in the forest[14]. Unelectrified public spaces limit the women’s ability to go out in the evening and get involved in other income-generating activities. It also increases the crime or sexual violence faced by women in dimly lit or unelectrified spaces[15]. Thus, electrifying public spaces makes it safer for women. A study in Tunisia found that girls felt safer going to school in the morning after street lights were installed along the way to the school[16].

Electrification can also help to reduce the domestic violence within the household[16]. A study in Afghanistan found that after houses were electrified, the women reported reduced domestic violence. Previously, when the child cried in the dark, the husband would get irritated and use violence against the wife. After electrification, if the child cried at night, the women would immediately switch on the light and silent the child[17]. Another study in rural India found that television which was introduced after electrification reduced the domestic violence rate and increased the rate of girls going to school[16].

Women Empowerment

Access to electricity increases the income generating opportunities for women, especially in small micro enterprise such as washing and ironing clothes, selling prepared food and beauty parlors [18][16]. A study found that access to electricity increased female employment by almost 10% in newly electrified communities in South Africa[19]. Another study in Nicaragua found that after reliable electricity, the percentage of rural women working outside increased by 23%, resulting in increased income for these households[11]. It is observed that when women receive extra income, they are also most likely to invest it in the betterment of their children and homes as compared to men[20]. Thus, access to increased income not only benefits the women but the entire family.

Involving women in renewable technologies also challenges the statuesque about what a woman can or cannot do as energy jobs are mostly considered man’s domain. In Kenya, women were trained as solar technicians and later hired to repair solar lanterns and install solar panels in the village. In a follow-up survey, men reported that seeing women solar technicians changed their perception about what a woman can or cannot do. The women, on the other hand, reported feeling more tconfident and empowered, after the training[21].

Thus, involving women in nontraditional jobs are important to uplift women’s status in society as well as break the existing stereotypes.

Socio-economic Factors

Different socio-economic factors determine how electricity is used in the household. Some of them are discussed below:

Unequal Decision-making power

In most rural households, men hold the decision making power about what kind of electric appliances can be bought[22]. Women’s opinions are either less valued or not heard during decision-making[2]. This means that men can either buy those appliances that mostly benefit them or could reject any new appliances that benefit women[23].

In a study in Zimbabwe, although women were the ones cooking, it was the men who decided on the adoption of the solar cookers. In some cases, they even rejected solar cookers, although it was beneficial to the women[24].

Another study in Kenya, Nepal and India found that women not only had less decision-making power in terms of what electric appliances to buy but also about where to install them (e.g. will the lights be installed in kitchens or not). This lack of decision-making power reflected the already existing gender gaps in these countries[25]. In female-headed rural households, the decisions might represent women’s preferences, but they are also highly influenced by the prevalent gender rules and cultural restrictions. Female-headed households are also generally poorer than male-headed and have limited purchasing power for new electric appliances. In a female-headed household where the husband is working abroad, the decision-making power could be strengthen by the remittance money send back home[25].

Unequal access to resources

As compared to men, women have less access to resources such as land, credit and markets[24][2]. Land in developing countries is mostly registered under a man’s name and women only have the right to use them and not own them. If the women become widows or decide to separate from their husband, they can also lose their land right[7]. This unequal access hinders a women’s ability to start a new business or expand their existing one. This also results in different demand for and use of electricity by men and women, depending on the resources they have[26].

Renewable Energy Technology (Mini-grids)

Adoption of Energy Technology is not Gender-neutral

Energy and technology are stereotypically considered a men’s domain[27][28]. Factors such as prevailing gender norms, gendered impact of energy and unequal decision-making power usually restrict the adoption of new energy technologies by women. In some cases, women might have access to these technologies but do not have control over it[10]. For example, in Nepal, when biogas was installed it was the men who decided on the location although women were the ones who had to fetch water and cow dung as well as mix it in the biogas. If women were involved, they could have decided on locations most suitable to them. Men were also mostly trained in the repair and maintenance of biogas technology[10]. This could be because women were either hesitant to get involved or the gender role dictated that only men carry out the technical work. The energy appliances also have a gender connotation to them and affect the choice of appliances. For example, appliances such as electric saw, water pumps and loudspeakers are usually viewed as male appliances whereas cooking appliances such as cook stoves are viewed as female appliances[25]. Thus, with the unequal decision-making power, the men might be first interested in investing in male appliances and then on female appliances.

Missed opportunity for End Use of Electricity

For a mini-grid to be successful, the beneficiaries (both male and women) need to be involved in all stages of the mini-grid 18 life cycle. This will help to identify the electricity demand for sizing the mini-grid accordingly and identify the potential end use activities as well as the communities’ willingness to pay[29]. This all contributes towards the sustainability of the mini-grid and the community can also reap maximum benefits. However, field experiences show that mini-grid projects without specific gender mainstreaming activities do not capture the need of the women and this ultimately led to the failure of the project (Skutsch, 1998). An electrification program in rural Zanzibar did not include gender mainstreaming activities in their first phase, assuming the planned activities to be gender-neutral. In the second phase, when they explicitly involved women, they found out that the electricity had not addressed the women’s needs. Two key institutions i.e. the village mills and the kindergarten that were of highest priority to the women were not electrified. This could be because men are not involved in flour milling or child-care and thus these institutions were not included in demand assessment[30].

Local Knowledge of Natural Resources

Women are knowledgeable of natural resources such as water resources and various flora and fauna in their surroundings[31]. However, this indigenous knowledge of women is often considered non-scientific and not valued[3]. Taking into account the women’s knowledge can help in better planning of the mini-grids[10][32][33]. E.g. while measuring the water table for micro hydro, rural women can be consulted.

Financial Benefit to the Mini-grid

Involving women within the operation and management of mini-grids also has financial benefits. As compared to young men, married women are more likely to stay in the village taking care of the family and not migrate to the cities for better opportunities, resulting in low turn-over of operators. The young men usually tend to migrate to cities after getting a training[34]. This reduces the cost of training new operators. Women are also aware of their local context/culture and know the potential customers for the mini-grid services. They also have first-hand experience of how access to energy could make their life easier so it is easier for women to interact with other women and share information about the end use of the electricity[2]. 19 Hence, involving women helps to acquire new creditworthy customers at a low cost. This has already been demonstrated by women entrepreneurs selling solar home systems[35].

Further Resources

- Gender - Introduction

- Gender Impacts of Energy Access

- Arising Inequalities through Energy Access

- Indoor Air Pollution (IAP)

References

- ↑ UNDP. (2007a). Gender mainstreaming: A key driver of development in environment & energy.Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/environmentenergy/sustainable_energy/gender_mainstreamingakeydriverofdevelopmentinenvironmentenergy.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 UNDP. (2001a). Generating Opportunities: Case studies on energy and women. Retrieved from

https://www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/environment-energy/wwwee-

library/sustainable-energy/generating-opportunities-case-studies-on-energy-andwomen/

GeneratingOpportunities_2001.pdf Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "UNDP, 2001a" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "UNDP, 2001a" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "UNDP, 2001a" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "UNDP, 2001a" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "UNDP, 2001a" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "UNDP, 2001a" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "UNDP, 2001a" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cecealski, E. (2000). The role of women in sustainable economic development. Retrieved from https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy00osti/26889.pdf

- ↑ UNDP. (2007b). Will tomorrow be brighter than today? Addressing gender concerns in energy for poverty reduction in the Asia-Pacific region. Retrieved from https://www.cleancookingalliance.org/resources/329.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Habtezion, S. (2012). Gender and energy. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/gender/Gender and Environment/PB3_Africa_Gender-and-Energy.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lambrou, Y., & Piana, G. (2006). Energy and gender in rural sustainable development. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/ai021e/ai021e00.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 World Bank. (2005). Gender and Natural Resources Management. Retrieved from

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGENAGRLIVSOUBOOK/Resources/Module10.pdf Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "World Bank, 2005" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Köhlin, G., Sills, E. O., Pattanayak, S. K., & Wilfong, C. (2011). Energy, gender and development what are the linkages? where is the evidence? Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTSOCIALDEVELOPMENT/Resources/244362- 1164107274725/3182370-1164201144397/3187094-1173195121091/Energy-Gender- Development-SD125.pdf

- ↑ UNEP. (2017). Atlas of Africa: Energy resources. Retrieved from https://www.icafrica.org/fileadmin/documents/Publications/Africa_Energy_Atlas.pdf

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Mahat, I. (2011). Gender, energy, and empowerment: A case study of the Rural Energy Development Program in Nepal. Development in Practice, 21(3), 405–420. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233010033_Gender_energy_and_empowerment_a_ca se_study_of_the_Rural_Energy_Development_Program_in_Nepal

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 IEA. (2017). Energy access outlook 2017: From poverty to prosperity. Retrieved from

https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/resource_docs/weo2017specialreport_energyaccessoutl

ook.pdf Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "IEA, 2017" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Mikul, B., Nicolina, A., Ruchi, S., Elisa, P., Elaine R., F., Susan, W., … Carlos, D. (2018). Access to modern energy services for health facilities in resource-constrained settings. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/156847

- ↑ Khandker, S. R., Barnes, D. F., Samad, H., & Minh, N. H. (2009). Welfare impacts of rural electrification evidence from vietnam. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/369601468027552078/Welfare-impacts-of-ruralelectrification- evidence-from-Vietnam

- ↑ Energypedia. (2019). Integration of gender issues. Retrieved December 27, 2019, from https://energypedia.info/wiki/Integration_of_Gender_Issues#Options_for_Integrating_Gender_Iss ues_into_Energy_Projects

- ↑ IIaria, B. (2019). Gender impacts of energy access. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://energypedia.info/wiki/Gender_Impacts_of_Energy_Access

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Köhlin, G., Sills, E. O., Pattanayak, S. K., & Wilfong, C. (2011). Energy, gender and development what are the linkages? where is the evidence? Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTSOCIALDEVELOPMENT/Resources/244362- 1164107274725/3182370-1164201144397/3187094-1173195121091/Energy-Gender- Development-SD125.pdf

- ↑ Standal, K. (2010). Giving light and hope in rural afghanistan: enlightening women’s lives with solar energy. Retrieved from https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/16072

- ↑ Barron, M., & Torero, M. (2014). Electrification and time allocation: Experimental evidence from Northern El Salvador. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/63782/1/MPRA_paper_63782.pdf

- ↑ Dinkelman, T. (2011). The effects of rural electrification on employment: New evidence from South Africa. The American Economic Review, 101(7), 3078–3108. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41408731?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- ↑ Glemarec, Y., Bayat-Renoux, F., & Waissbein, O. (2016). Removing barriers to women entrepreneurs’ engagement in decentralized sustainable energy solutions for the poor. AIMS Energy, 4(1), 136– 172. Retrieved from http://www.aimspress.com/journal/energy

- ↑ Winther, T., Ulsrud, K., & Saini, A. (2018). Solar powered electricity access: Implications for women’s empowerment in rural Kenya. Energy Research and Social Science, 44, 61–74. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629618303694

- ↑ Clancy, J. S., Skutsch, M., & Batchelor, S. (2002). The gender-Energy-Poverty NEXUS: Finding the energy to address gender concerns in development. Retrieved from https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/the-gender-energy-poverty-nexus-finding-the-energyto- address-gen

- ↑ Clancy, J. S., Skutsch, M., & Batchelor, S. (2002). The gender-Energy-Poverty NEXUS: Finding the energy to address gender concerns in development. Retrieved from https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/the-gender-energy-poverty-nexus-finding-the-energyto- address-gen

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Tucker, M. (1999). Can solar cooking save the forests? Ecological Economics, 31, 77–89. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800999000385

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Winther, T., Ulsrud, K., Matinga, M., Govindan, M., Gill, B., Saini, A., … Murali, R. (2020). In the light of what we cannot see: Exploring the interconnections between gender and electricity access. Energy Research and Social Science, 60. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629619306000

- ↑ _

- ↑ _

- ↑ Pachauri, S., & Rao, N. D. (2013). Gender impacts and determinants of energy poverty: Are we asking the right questions? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(2), 205–215. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877343513000389

- ↑ UNDP. (2001a). Generating Opportunities: Case studies on energy and women. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/environment-energy/wwwee- library/sustainable-energy/generating-opportunities-case-studies-on-energy-andwomen/ GeneratingOpportunities_2001.pdf

- ↑ Winther, T. (2011). Electricity’s effect on gender equality In rural Zanzibar, Tanzania. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tanja_Winther/publication/241875587_Electricity’s_effect_o n_gender_equality_in_rural_Zanzibar_Tanzania_case_study_for_Gender_and_Energy_World_D evelopment_Report_Background_Paper/links/557068d008aeffcab353be05/Electrici

- ↑ Balakrishnan, L. (2000). Renewable energy as income generation for women. Renewable Energy, 19(1– 2), 319–324. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960148199000476?via%3Dihub

- ↑ UNDP. (2013). Women and natural resources unlocking the peacebuilding potential. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/crisis prevention/WomenNaturalResourcesPBreport2013.pdf

- ↑ UNDP, & ENERGIA. (2004). Gender and energy for sustainable development: A toolkit and resource guide. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/environmentenergy/ sustainable_energy/energy_and_genderforsustainabledevelopmentatoolkitandresourceg ui.html UNEP. (

- ↑ Angelou, N., & Roy, S. (2019). Integrating gender and social dimensions into energy interventions in Afghanistan. Retrieved from https://energypedia.info/images/2/21/Integrating_Gender_and_Social_Dimensions_into_Energy_ Interventions_in_Afghanistan.pdf

- ↑ Glemarec, Y., Bayat-Renoux, F., & Waissbein, O. (2016). Removing barriers to women entrepreneurs’ engagement in decentralized sustainable energy solutions for the poor. AIMS Energy, 4(1), 136– 172. Retrieved from http://www.aimspress.com/journal/energy