Pay-as-you-go Approaches (PAYGO)

Overview

Pay-as-you-go (PAYGO): Companies sell services or products to customers through a pre-paid model. In case of products PAYGO is a kind of paying in small installments to persons that cannot afford or are not willing to buy products in cash. Under PAYGO, the companies not only provide product and services but also the necessary finance to consumers. Customers usually pay 10-20% as upfront cost and rest as loan over a period of 1-2 year. For PAYGO, it may take more than 3 years to convert product inventory into cash flow [1].

This article explains briefly how PAYGO works for customers paying for electric services from off-grid solar systems as well as for the companies offering this service.

- For SHS, see also Fee-For-Service_or_Pay-As-You-Go_Concepts_for_Photovoltaic_Systems

Pay-as-you-go Approaches

Definition: PAYGO

Pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) is a financing technology that allows end-users to pay for solar energy in weekly instalments or whenever they are financially liquid. PAYGO is a pioneering, game-changing credit system that removes the initial financial barrier to solar energy access by allowing consumers to make a series of modest payments to purchase time units for using solar electricity instead of paying upfront for the entire solar lighting system.[2]

PAYGO is emerging as a solution that addresses both end-customer affordability and provides sufficient margins to fuel operational models that can scale.[3]

PAYGO companies can be divided into three groups: [4]

- distributed energy service companies (DESCO): they provide a given level of energy service in exchange for ongoing payments

- asset finance or microloan providers: they offer rent-to-own models

- business-to-business (B2B) intermediaries: supplying hardware and software support from global operations to last-mile energy service and payment logistics

The first PAYGO companies were vertically integrated companies (one-stop-shops). They did all steps: [5]

- hardware and software design

- sales

- distribution

- service

- financing

While most of them have competencies in 3-4 areas, financing became a challenge for them. Expanding and scaling is hampered by two factors: As there are no financial intermediaries, currency risks are an obstacle to growth; and as customers pay within years, working capital is limited. [5]

As a recent development, more mirco financing insitutions enter the market. See Market Overview: Disaggregating the PAYGO value chain.

PAYGO companies use a variety of combinations of payment systems:

- mobile money (40%)

- scratch cards and other options (60%).

They use enforcement mechanisms like remote GSM connections and keypad verification.[4] Because most of them use mobile payments, PAYGO is cheaper than traditional microfinance options.

In the energy access sector, PAYGO approaches are mostly used to sell picoPV and SHS solar products, but also mini-grids can be operated implementing a PAYGO tariff. [6]

How it Works: PAYGO for customers

There are different systems, how PAYGO works. A relatively simple system is using recharge scratch cards, where each card has a code that is revealed by scratching off the silvery layer. The customer enters this code either into the keypade of his system or into their phone. The backend computer systems receive the code, verify it, and finally the PAYG operator unlocks the system. However, the scratch card method requires a complex stock of cards to manage and distribute across agents’ network.

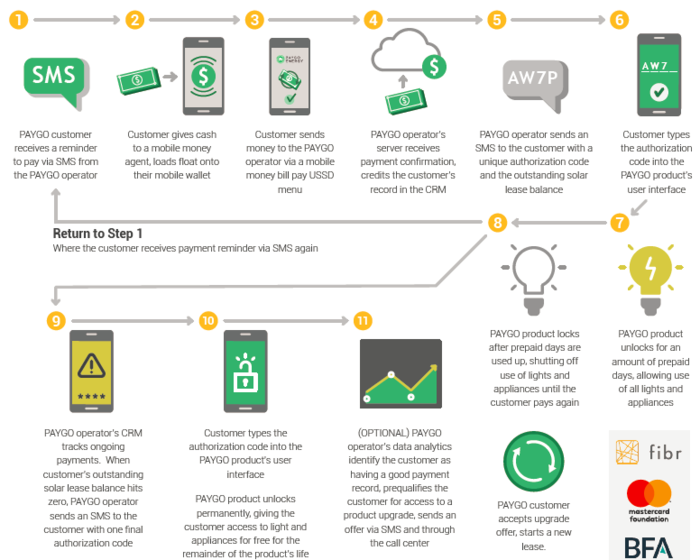

Another system is presented in the following figure. Here, the code is sent to the customers via SMS. This system is also working with an agent, which plays an important role in the uptake and use of mobile money based PAYG systems in rural areas, where people do not often use phones for mobile money transaction or cannot read. Agents help customers, who are hesitant to use mobile money or don't know how it works, to make transactions so that mobile money services become accessible to communities with low digital financial literacy.

Figure: PAYGO for customers step-by-step

Source: Winiecki et al. 2017.[7]

In other systems, customers make a payment to their account at the PAYG provider through a platform of the mobile network operator. Payment notification is sent to the PAYG payment service of the provider, which activitates a credit and unlocks the system of the customer. In some cases, customer can also pay with airtime by transfering airtime to the PAYG provider.

Examples:

- The largest company in terms of scale is M-KOPA, which reached 500,000 SHS in April 2017.[8]

- The Indigo Duo of Azuri consists of a power unit using a lithium iron phosphate battery, a 2.5W solar panel, two light points using LEDs, and adapters to enable the user to charge a phone. In Rwanda, the installation fee is RWF 6,600 (USD 9), and monthly payments of RWF 3,500 (USD 5). After those payments, the customer gets a code to make the unit usable. Without payments the system shuts down. After 21 months, customers own the system after paying one last single “unlock fee” of RWF 6,600 (USD 9).[9]

- D.light customers in Kenya put a payment of USD 25 down, and continue with payments of 40 cents per day for a year via a choice of mobile money services (interest-free). The D30 off-grid home solar system is unlocked with the initial payment, remains unlocked as long as succeeding payments are made on time, and is unlocked in perpetuity once the system is paid for in full.[10] Historically focused on cash sales, D.Light has raised a total of USD 22 million in 2016, primarily aiming to boost its PAYGO business.[11]

- Mobisol’s solar systems comprise several ultra-efficient LED light sets, a portable lantern, mobile phone charger kit, large high-performance flat-screen LED TVs up to sizes of 32″, portable radio and balance-of-system components including wiring and switches. Customers get a three-year flexible payment plan via mobile money as well as extended warranties, free installation and free maintenance for three years.[12]

- Ugandan Mobile Pay-Go Solar Provider Fenix International doubled the number of customers in the year 2016 to 100,000. Fenix deploys solar leases of over USD 20 million. Fenix’s ReadyPay Power high-efficiency solar products and services worth 1.2-MWs serve over 600,000 Ugandan households.[13][14]

- Power Mundo in Peru is successfully implementing PAYG projects with support from ADB and others. The main aim of the project is to develop a distribution network for efficient, low cost off-grid picoPV and SHS energy products that residents in rural Peru can afford while at the same time creating local employment opportunities that can raise residents’ incomes.[15]

- In Kenya, PAYG is also offered for cooking gas by M-Gas - people do not have to buy the cooking gas cylinder or burners which often costs more than KES 6,000 and refilling a cylinder costs above KES 2,000 per cylinder. With this approach, the company provides a cylinder with a smart metering and people only use the cooking gas that they need.

Conclusion

This article offers a definition for PAYGO approaches and shortly explains how it works with examples from the major companies.

Further Information

- Financing and Funding Portal

- Market Development of PAYGO

- Advantages and Disadvantages of PAYGO Approaches

- PAYGO Approaches: Overhyped or Justified

- Role of Supporting Environment in Fostering Pay-as-you-go Approaches (PAYGO)

- Fee-For-Service or PAYGO for PV systemsincluding information about the major PAYGO companies

- A list of relevant PAYGO companies and an in-depth explanation about PAYGO approaches: Bennu Solar Ltd. ‘PAYG Solar. Information on PAYG Enabled Solar Solutions |Bennu Solar’, 2017. Link.

- Lepicard, François, et Al. ‘REACHING SCALE IN ACCESS TO ENERGY: Lessons from Best Practitioners’. Hystra, 2017. https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/recource_docs/hystra_energy_report.pdf.

- Moreno, Alejandro, Asta Bareisaite, and others. ‘Scaling up Access to Electricity: Pay-as-You-Go Plans in off-Grid Energy Services’. The World Bank, 2015. Link.

- Lighting Global (2015): Alstone, Peter Michael. Connections beyond the Margins of the Power Grid Information Technology and the Evolution of Off-Grid Solar Electricity in the Developing World. University of California, Berkeley, 2015. Link.

- Winiecki, Jacob, and Kabir Kumar. ‘Access to Energy via Digital Finance: Overview of Models and Prospects for Innovation’. Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Link.

References

- ↑ The World Bank, 2020. Funding the Sun : New Paradigms for Financing Off-Grid Solar Companies- https://energypedia.info/wiki/Publication_-_Funding_the_Sun_:_New_Paradigms_for_Financing_Off-Grid_Solar_Companies_(English)

- ↑ Paul Winkel, ‘Startup Peru Winner | Powermundo’, 2016, http://www.powermundo.com/media-resources/news-events/startup-peru-winner/.

- ↑ Jacob Winiecki, Michelle Hassan, and David del Ser, ‘Briefing Note PAYGo Solar: Lighting the Way for Flexible Financing and Services’ (FIBR, mastercard foundation, BFA, 2017), https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/resource_docs/finalfibrbriefingnotepaygosolarjuly2017.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Andrew Scott and Charlie Miller, ‘Accelerating Access to Electricity in Africa with Off-Grid Solar - - Research Reports and Studies - 10230.Pdf’ (Overseas Development Institute, 2016), https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10230.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Daniel Waldron, ‘Solar Energy: A New Frontier for Microfinance’, CGAP, 17 April 2017, http://www.cgap.org/blog/solar-energy-new-frontier-microfinance.

- ↑ Alejandro Moreno, Asta Bareisaite, and others, ‘Scaling up Access to Electricity: Pay-as-You-Go Plans in off-Grid Energy Services’ (The World Bank, 2015), http://bit.ly/2wkwf4f.

- ↑ Winiecki, Jacob, Michelle Hassan, and David del Ser. ‘Briefing Note PAYGo Solar: Lighting the Way for Flexible Financing and Services’. FIBR, mastercard foundation, BFA, 2017. https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/resource_docs/finalfibrbriefingnotepaygosolarjuly2017.pdf.

- ↑ Lepicard, François, Simon Brossard, Jessica Graf, Lucie Klarsfel, and Adrien Darodes de Tailly. ‘REACHING SCALE IN ACCESS TO ENERGY: Lessons from Best Practitioners’. Hystra, 2017. https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/recource_docs/hystra_energy_report.pdf.

- ↑ J-C. Berthélemy and V. Béguerie, ‘Field Actions Science Reports. Decentralized Electrification and Development’ (Veolia Insitute, 2016), 92, http://www.energy4impact.org/file/1783/download?token=TA1nhUl9.

- ↑ Andrew Burger, ‘Competition Heats Up in Kenya’s Off-Grid, Mobile Pay-Go Solar Market’, Microgrid Media, 21 March 2017, http://microgridmedia.com/competition-heats-kenyas-off-grid-mobile-pay-go-solar-market/.

- ↑ Itamar Orlandi, ‘Q1-2017-Off-Grid-and-Mini-Grid-Market-Outlook’ (Bloomberg Finance L.P., 2017), https://data.bloomberglp.com/bnef/sites/14/2017/01/BNEF-2017-01-05-Q1-2017-Off-grid-and-Mini-grid-Market-Outlook.pdf.

- ↑ Kennedy Kangethe, ‘Solar Solutions Provider to Open 20 Stores in Kenya’, Capital Business, 17 March 2017, https://www.capitalfm.co.ke/business/2017/03/solar-solutions-provider-open-20-stores-kenya/.

- ↑ Andrew Burger, ‘Uganda Mobile Pay-Go Solar Provider Doubles Customer Base to 100,000 in 12 Months’, Microgrid Media, 25 January 2017, http://microgridmedia.com/uganda-mobile-pay-go-solar-provider-doubles-customer-base-100000-12-months/.

- ↑ Allegra Fisher, ‘Pay-to-Own Solar Energy System Doubles Off-Grid Customer Base in Just 12 Months’, Fenix International, 22 January 2017, http://www.fenixintl.com/2017/01/22/pay-to-own-solar-energy-system-doubles-off-grid-customer-base-in-just-12-months/.

- ↑ Andrew Burger, ‘Off-Grid Solar Start-Ups Pierce the ¨Heart of Darkness¨’, Microgrid Media, 8 December 2016, http://microgridmedia.com/off-grid-solar-start-ups-pierce-%c2%a8heart-darkness%c2%a8/.