Solar Battery Charging Stations

You can also download the paper on rural electrification by battery charging stations as PDF.

Rural Electrification by Battery Charging Stations

In rural areas of developing countries many households do not have access to electricity and power their radios with dry cell batteries or use candles and kerosene lamps for domestic lighting. Some employ car batteries that are charged in battery charging stations for lighting and entertainment.

Battery charging stations are usually not the first choice for rural electrification, but they can be viable in remote areas were no other alternatives exist and the income of the population is too low to invest in other solutions as for example solar home systems. Battery charging stations provide services for a low energy demand and therefore, are a temporary solution until other energy resources are available. Until then, however, many years may pass.

In electrified areas grid-based battery charging stations can be seen as indirect grid densification as those that have no direct connection in their home profit indirectly from the existing electricity infrastructure.

Lead-acid wet cell car batteries are often used for providing a minimum of electricity services for the local population in many developing countries. They are usually available on the market, in some countries also produced locally and the most common type in use to cover basic energy needs. They are the least cost option, but have a low allowable depth of discharge and a short life time compared to deep-cycle batteries designed to provide a steady amount of current over a long period.

The use of electricity from car batteries can improve the living conditions of its users to a large extent. Battery powered lamps not only improve domestic working conditions at night in particular for women but also enhance studying conditions for children because they provide brighter light than kerosene lamps and candles. Furthermore, they do not emit noxious pollutants accounting for a healthier indoor air.

Battery-driven radios and TVs are highly valued for information and entertainment. Small radios are often powered by expensive dry cell batteries which are thrown into the nature after being used. Power from batteries charged in a battery charging station is an environment-friendlier option if their disposal and recycling, after a lifetime of up to three years, is guaranteed.

The possibility to recharge mobile phones is crucial for the access to modern communication and can help people in rural areas to obtain information and facilitate commercial operations.

To a smaller extent, the provision of battery charging facilities gradually contributes to raising incomes derived from small businesses and handicraft, especially in communal market towns. Shop owners, for example, can open their shops in the evenings, and thus not only might raise their income, but also deliver an improved service to the community. Usually car batteries are transported to the nearest grid, diesel or solar-based battery charging station where they are connected and recharged for a fee. In addition to the fee, users pay transport costs according to the distance to the next station. Depending on the household’s income, energy demand, battery quality and size, batteries are recharged between two to four times a month.

Diesel generators can charge a limited number of batteries at a time, and service costs highly depend on diesel costs. Grid based charging stations are usually less subject to quantity restrictions and changing diesel prices, but might be located far from the rural population.

Solar battery charging stations (SBCS) constructed in rural areas are an alternative solution to provide the local population with energy for basic needs and reduce the time and expenses required for travelling.

Those stations consist of

- at least one photovoltaic panel and

- a charge controller to prevent batteries from overcharging.

The size of a SBCS and the number of PV panels installed vary according to insolation (solar radiation energy received on a given surface area at a given time) and energy demand (number of batteries to be charged). SBCS can be operated in different ways.

They can be

- property of the municipality

- privately owned.

The users may pay

- a fee per charge

- a monthly fee

- for the recharge of their own batteries or

- for renting a recharged battery owned by the operator.

SBCS can simply offer recharge service or include a shop selling other solar and electric equipment.

Example ‘Energising Development’ Mali

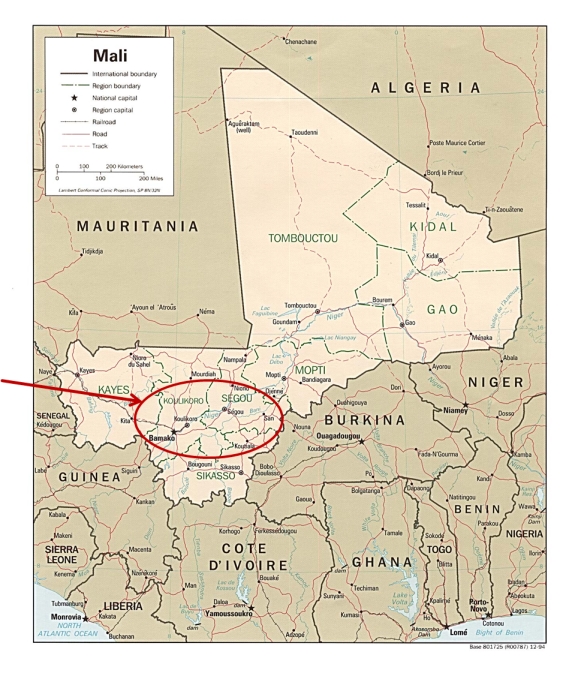

Mali's power grid covers only a few urban areas and more than 97 % of the rural population live without access to electricity. In order to enhance living conditions of the population photovoltaic battery charging stations were installed in seven rural municipalities as a part of the Malian Communal Electrification Programme ‘Électrifcation Communale’ (ELCOM) which is a unit of the Local Government Support Programme (‘Programme d’Appui aux Collectivités Territoriales’ (PACT)) and forms an integral part of the ‘Energising Development’ (EnDev) initiative, a German-Dutch partnership. ELCOM’s objective is to provide access to electricity in rural areas of Mali, not only by constructing SBCS for local people, but also by installing communal solar power systems for key public buildings (health centres, schools, town halls) and solar street lights.

The SBCS are property of the municipality and the operation is delegated to a private service provider who runs them on a fee-for-service basis. The fee is used to cover the maintenance and upgrade costs of the SBSC as well as the maintenance costs for the communal PV systems installed in schools, health centres and town halls.

From the beginning of 2008 until the beginning of 2009, 26 SBCS were constructed. The municipalities contributed to the expenses in cash and in kind (labour by the villagers) with an average proportion of 10 to 20 % of the initial investment costs. The remaining costs were covered by EnDev funding.

Most of the SBCS constructed have a recharge capacity of three batteries per day.

They consist of

- a building with recharge terminal,

- six PV panels with a capacity of 65 Wp each,

- a charge controller and

- necessary equipment such as cables and fittings.

Some SBCS have a capacity of six batteries per day (capacity of 780 Wp (= 12 panels), two charge controllers) and one has a capacity of nine batteries. Furthermore, each SBCS has its own small PV system for lighting consisting of a 65 Wp panel, a charge controller, a battery and lamps for inside and outside.

ELCOM Intervention Area: Regions of Ségou and Koulikoro

Overview: Municipalities with SBCS Installed within the Programme

|

Municipality |

Population (Projection 2008) |

No. of SBCS |

Capacity of SBCS batteries/day |

Total batteries/ day | ||

|

3 |

6 |

9 | ||||

|

Katiéna |

27,405 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

- |

27 |

|

Tiélè |

20,133 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

- |

21 |

|

Kamiandougou |

15,330 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

- |

15 |

|

N'Koumandougou |

12,371 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

- |

15 |

|

Sobra |

9,282 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

9 |

|

N'Gassola |

5,549 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

- |

9 |

|

Bellen |

5,409 |

3 |

3 |

- |

- |

9 |

|

Total |

95,479 |

26 |

18 |

7 |

1 |

105 |

Costs, Revenues and Operational Model

Investment Costs

A SBCS which has a charging capacity of three batteries (six 65 Wp PV panels, one charge controller) costs approximately FCFA 5.2 million (~ € 7.900), including the costs for the construction of the building. The costs for SBCS with a capacity of six batteries or more are higher according to the prices for PV panels and charge controllers.

The Customers

Firstly, the user has to possess a battery that can be recharged in a SBCS. As batteries are very expensive in proportion to the income of the rural population, many people cannot afford them. Hence, they are excluded from the services SBCS offer. New batteries with a capacity of 70 Ah (typical car batteries) cost about 40,000 FCFA (€ 61). Second hand batteries cost between 10,000 and 15,000 FCFA (€ 15 to 23).

The charge of a 70 Ah battery in Bamako or in regional and district centres costs FCFA 500 (€ 0.8). Additional transport costs to overcome distances of up to 100 km can lead to a total expense of FCFA 1,000.

FCFA 750 per charge in communal SBCS are considered to be a competitive price compared to pre-existing conditions (long journeys, travel costs, recharge quality).

Compared to the low income of the rural population, battery charging be it in a conventional charging station or in a SBCS, is very expensive. ELCOM team members estimate that a person in a rural area can earn between FCFA 5,000 and 6,000 (€ 8 to 9). This means that recharging a battery twice a month accounts for a proportion of more than 25 % of a monthly income.

The Operator

The private operator who takes care of the charging stations in each municipality has to pay a fixed monthly fee, which is divided between the amortisation fund, the town hall and the management committee. The management committee, established in each municipality, is responsible for supervising the operation of the solar installations. It consists of village representatives as well as the operator and is responsible for the operator renting fee, for repair of equipment and for investments. In this way mutual control of the involved actors is guaranteed. The operator’s fee is used to pay necessary repairs of all the installations including those generating power for key public buildings and the street lights. Spare parts if necessary and potential upgrade costs have to be covered by the revenue from the SBSC as well.

Furthermore, the operator has to pay the wages of the technicians. His profit has to be covered by the remaining amount. In order to be profitable the SBCS have to run on 60 to 70 % of the total capacity in the case of rural Mali.

Experiences

After their installation, the SBCS are operating reliably. They are known and reputed among the clients for their very high quality of charge, which allows battery utilisation for about two weeks (15 to 20 days, depending on the quality of the battery). The quality of charge of other BCS is usually much lower (utilisation of 2 to 5 days) as they do not apply charge controllers. Nevertheless, the advantages and potential savings on energy expenditures have to be explained to the costumers, who often only see the higher price, not considering the superior price-service ratio and the amount of money saved on transport costs. Word of mouth seems to be the most effective means of marketing.

With all the SBCS running approximately 1,100 batteries are charged per month. As a result 6,470 people currently profit from the SBSC and have access to electricity. However, the number and the capacity of the SBCS in some of the municipalities were over-estimated as the number of costumers’ remains low and the SBSC are running on approximately 35 to 40 % of their capacity on average. This is partly due to the lack of rechargeable batteries. Most of the batteries brought to the SBCS are car batteries that are actually not suited for delivering a steady amount of current over a longer time. Solar batteries designed for that purpose cost even more than car batteries and are not readily available in rural areas. Many households cannot even afford to buy a car battery and others have second hand batteries which are in such a poor condition that recharging them is impossible. Many potential customers had to be rejected by the operator due to the bad state of their battery. However, even those who do not own a battery profit indirectly from charging services as they can watch TV in their neighbours’ home or have their mobile phone recharged by someone owning a battery. The maintenance of all solar installations including communal PV systems and an acceptable level of profit for the operator is not guaranteed if the degree of capacity utilisation does not reach 60 to 70 %. Currently, only in one municipality is the revenue high enough for the operator to pay the total fee. In the other municipalities the operators meet on a monthly basis with the management committee and representatives from the town hall to discuss the repartition of the revenue. In this way it is avoided that the operator is discouraged.

Almost all municipalities have had large difficulties in mobilising their share. This led to major delays in the construction of the SBCS as the communal contribution had to be paid directly to the construction companies. The municipalities, who were also the contracting authority, were unwilling to put the construction companies under pressure to terminate the construction as they were depending on the goodwill of the contracted companies to pre-finance the communal share. These dependencies sometimes resulted in less transparent awarding of contracts to construction enterprises. In addition, the inhabitants of the municipalities could not be easily mobilised to contribute their manual support for construction.

A positive development of the programme is that the private operators have begun to install solar home systems, sell solar lanterns and provide after-sales services in the rural municipalities that go beyond the original ELCOM intervention.

Lessons Learnt

In order to avoid delays in the construction for the future, greater efforts will be made in the selection of the municipalities involving the prefectures, sub-prefectures and the tax inspectors which should facilitate the identification of municipalities which are able to pay their own contribution. The municipalities will outsource the responsibility for supervising the construction process to ELCOM, thus avoiding problems with the construction companies from the beginning. Furthermore, the in kind contribution by the village community will be not included any more and more emphasis will be placed on a direct financial contribution.

Monthly monitoring of SBCS management during the first months of operation is absolutely necessary. The technicians as well as the operators need support to use the provided management tools.

Technical monitoring has to be done about every two months during the first six months to demonstrate presence and prevent misuse of the equipment installed. It also helps in capacity building regarding end-users, operators and technicians. For technical monitoring it will be necessary to develop a maintenance plan that operators can follow when they visit the installations.

In order to avoid over-capacity and reduce costs for both, the project and the municipalities, the number of SBCS, their capacity and the selection of the villages where they will be located, will be based on the result of detailed feasibility studies which will take place in the intervention area in the future. In order to ensure business profitability, wealthier municipalities should be selected where people have the means to buy quality batteries and charge them on a regular basis. Small commercial centres were electricity is required for productive use, are also better suited. Other factors such as network coverage for mobile phones and TV signal coverage have also to be taken into consideration. This experience shows the difficulty in providing electricity to the poorest and the necessity of having customers which have a certain level of income to assure the sustainability of the intervention.

Key Success Factors for SBCS

In general SBCS are comparably expensive, but can be an economic solution

- in remote areas, which are not connected to the grid,

- where diesel fuel costs and battery transport costs are high and

- income and

- energy demand are low.

Important aspects to be considered for the success of SBCS are

- extensive marketing,

- additional services to be offered such as renting/selling batteries or recharge services for mobile phones,

- training of all local operators and technicians.

⇒ Back to Solar Section