Business Models for Sustainable Agrifood Systems

Introduction

A business model describes the core strategy of an organization, how the company produces, distributes prices and promotes its products. Within the Energy-Food Nexus, depending on the size and type of the agri-business, different kinds of energy needs require different business models to improve investment strategies, implementation approaches and to remain under optimized conditions on the market.

Agri-Food Enterprises in the Energy-Food Nexus

Agricultural enterprises range from basic subsistence to large commercial, corporate farms. Their size strongly influences the ability to manage and incorporate renewable or energy efficient technologies and must be considered throughout the techno-economic analysis of agricultural value chains.

Small-scale agricultural households produce food for their own consumption. Subsistence producers use very low energy inputs, and often lack the financial resources to invest in sustainable energy solutions. However, coordinated networks of subsistence farmers can benefit from renewable energy systems, such as small-scale hydro, wind and solar powered systems. Small Family Units are slightly larger and able to provide fresh food to local markets and/or to processing plants. They can also have access to renewable energy technologies such as solar heat for crop drying, on-farm produced biogas for cooking and PV systems for electricity production.

Privately owned Small Businesses can also be family-managed but operate at a slightly larger scale and employ several staff. Their capital allows them to reduce their fossil fuel dependence by investing in renewable energy, providing additional benefits for the surrounding local community.

Larger food enterprises are usually dependent on higher direct and indirect external energy inputs. So-called Large Corporate Businesses usually have access to finance for capital investments in renewable energy technologies and the produced energy may be used on-farm or sold off-farm for additional revenue. Read more…

Business Models for the Energy-Agriculture Nexus

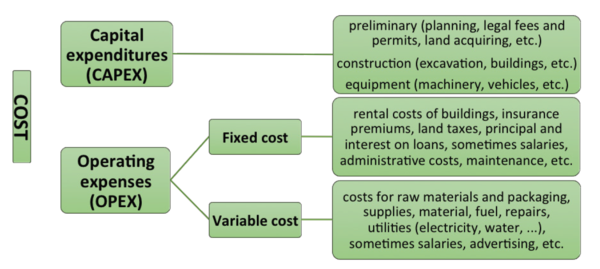

When going into business, an additional value that customers are willing to pay money for needs to be created. In order to estimate the market potential of this product or service, market research and analysis need to be carried out first. Before conducting financial calculations or starting to implement any business activity, the basic elements need to be determined. This includes determining the total costs of a project, which can be divided into capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operating expenses (OPEX), whereby latter can be subdivided into fixed and variable costs.

Deciding on an investment can be difficult, especially if a high investment is required, if it is a long-term investment, or if several investment alternatives are available. Capital Budgeting provides an overview about eventual returns on investments and helps to identify the most profitable investment options. There are two principal approaches for assessing the profitability of investment projects: the static and the dynamic approach. The first method is useful for a first impression, as well as for ranking different investment options. It is based on the use of the profitability indicator Payback Time (PBT), which allows identifying the investment option with the shortest payback period. The dynamic approach considers the time value of money, which is important especially for long-term investments. Here, the main indicators are the Net Present Value (NVP) and the Internal Rate of Return (IRR). All investment assessment methods have their strengths and weaknesses; thus, it is recommended to apply at least two before making a decision.

When there is not enough money to make an investment, microfinance approaches can help. These split the often relatively high initial investment costs into smaller monthly rates. Especially within energy projects in small scale agricultural enterprises, this is a common approach that includes services such as insurance, leasing, savings, cash transfer and credits, provided by microfinance institutes (MFI) that can be NGOs, banks, credit and savings cooperatives and associations. Read more…

Case Studies

Business Plan for Solar Processing of Tomatoes

Economic development in remote rural areas can be enhanced by adding value to farmers’ agricultural raw products. A GIZ project in Ethiopia, for example, supported farmers in processing raw tomatoes into dried tomatoes and tomato paste. In order to be able to compete with already established large-scale processing plants, it is fundamental to set up a business plan, which includes a Production Plan, where the different steps and the required technologies are determined, such as for food preparation and sterilization of the product packaging. A Marketing Plan identifies how to meet the customers’ needs better, for example by selling smaller portions packaged in user-friendly PET-bags. Furthermore, a Financial Plan is necessary for any investment, as it also considers depreciation costs. Finally, in order to guarantee the long-term sustainability of the project, a Management Plan needs to be set up, determining which activities require which amount of labour input. Read more…

Small Scale Oil Seeds Processing

The GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH) Sustainable Land Management Program (SLMP) and the Tigray Agricultural Marketing Promotion Agency (TAMPA) started a collaboration for the promotion of small-scale oil seeds processing in Tigray. The target groups were oil seeds producing farmers organized in user groups, which were provided with processing units (manually operated oil expeller) in 13 woredas (districts) in Ethiopia. The project aims to encourage oil seed farmers to add value to their raw products. The final product is a healthy virgin oil from Noug (Niger Seed) or Suff (Safflower) which will improve nutrition of the farmers’ families and generate income. The by-product oil cake can serve as protein concentrate for animal feed. In order to determine the profitability of this device, performance data needs to be set upon financing costs, which involve all processing steps, and further costs from maintenance and depreciation. Read more…

ColdHubs

ColdHubs are modular, solar-powered walk-in cold rooms for 24/7 off-grid storage and preservation of perishable foods. ColdHubs can be installed in major food production and consumption centres such as markets. Farmers place their produce in clean plastic crates inside the cold room, extending the freshness from two days to about 21 days. It addresses the problem of post-harvest losses of fruits, vegetables and other perishable food. In order to assess its potential for implementation, the financial feasibility was tested by evaluating three different business models: the current ownership model, the potential third-party/user- and the franchising model. Storage capacity and usage frequency were two relevant factors for the evaluation. In a third-party model, the users purchase the ColdHub, financing it through either a loan from the bank or supplier, or through a lease-to-own model where they pay a monthly leasing fee to the supplier. Raising cooling fee prices, gaining specific interest rates on loans or leasing fees, and increasing the down payment of the initial investment are some options of increasing attractiveness for investors. Otherwise, the internal rate of return (IRR) would be too low, making a bank loan unrealistic. A franchising model allows different franchises to lease ColdHubs’ branding and technology, resulting in faster upscaling, but less profit for the franchises. These would operate the hubs and collect cooling fees, which would need to be raised in order to cover the debt. This measure would be feasible, as implementation of the cold rooms would generate additional earnings from decreased food waste and higher selling prices from fresh food. The combination of the franchising model with the current ownership model would allow a moderate upscaling of ColdHubs by 2023. Read more…

Publications & Tools

Water-Energy-Food Nexus: Agri-food Business Cases

The agri-food sector accounts for 80 percent of total freshwater use and 30 percent of total energy demand, producing 12 to 30 percent of man-made GHG emissions worldwide. As global food demand is expected to increase 70 percent by 2050, understanding the interlinkages between water, energy and food is essential to tackle the challenges of sustainable agricultural production. Nexus-driven solutions for crop management, processing, distribution and retailing are key to mitigate risks, reduce costs and raise productivity. However, this transition requires upfront investments and long-term thinking, which often leaves behind small and medium-sized enterprises. Therefore, it is essential that large enterprises generate nexus value across supply chains, reducing risks and initial costs for SMEs through mutually beneficial business partnerships. Additionally, governments have a fundamental role in promoting nexus solutions, as private enterprises cannot be expected to finance public benefits alone. Therefore, creating incentives and promoting awareness among small and medium enterprises together with policy making on food-water-energy issues is essential to enable long-term investments in sustainability. Read more…

Biomass Energy Sector Planning Guide (BEST)

Although negative perceptions of biomass energy are widespread, it is not necessarily an unsustainable or backward fuel. Its sustainability depends on the practices applied in the value chain, including forest management techniques and the efficiency of conversion and use. Moving biomass activities to the formal sector by establishing a suitable and functioning regulatory framework provides security for producers and traders to invest in better and more sustainable production methods. The Biomass Energy Sector Planning Guide assists stakeholders in government institutions in the development of efficient and coordinated management strategies in the biomass energy sector. These are developed along six stages: analysis and team formation, baseline sector analysis, scenario development, intervention formulation, strategy and action plan monitoring, and finally adoption and implementation of the agreed activities. The Guide can also be used as a tool by civil society actors and donor agencies for raising awareness about the importance of the biomass sector. Read more…