Conducting Productive Use of Energy (PUE) Assessments

Introduction

Productive Use of Energy (PUE) has increasingly been regarded as the key means of improving Average Consumption per User (ACPU), Average Revenue per User (ARPU) and electricity utilization rate for mini-grids. For instance, CrossBoundary (2023) notes that:

“Productive use appliances contribute significantly to the profitability of a mini-grid. For example, a grain mill operator on one of the Lab developer’s existing sites consumes 300kWh/month of electricity in a region where the median mini-grid customer consumes 3kWh/month. This single grain mill operator therefore consumes as much power as one hundred typical customers. Productive use appliances like grain mills typically have power ratings of 1,000-10,000 watts (1-10kW), 10x more than commercial appliances like shop fridges (50 – 100 watts), and 100x more than household appliances like TVs (30 – 50 watts). Moreover, productive use appliances are typically operated during the day when electricity from solar mini-grids is cheapest for developers to provide.”

However, the viability of PUE technologies differs by geographical region and community. For instance, the capital cost of a solar powered irrigation system (SPIS) depends on the peak daily water needs of a crop, solar irradiance and other key factors (Power Africa, 2022: 25). Therefore, at the most general level, the crops with the greatest potential for improved yield by irrigation differ by state (Power Africa, 2022: 13).

Even the suitability of each type of irrigation technology (e.g. surface irrigation, sprinkler, low-pressure drip irrigation and high-pressure drip irrigation) depends on the type of crop cultivated in a community and the availability of water sources (Figure 1).

Similarly, the suitability of milling machines, threshers and other agricultural equipment depends on the crops cultivated; while the suitability of electric two-wheeled vehicles in rural areas depends on various factors including the state of roads, the incomes of rural residents, and the types of productive activities available which require light transportation.

Steps in Undertaking PUE Assessment

Site Screening (Pre-Feasibility Assessment)

PUE assessment may be undertaken as a part of a mini-grid development project (“Linked assessment”) or as a standalone assessment (e.g. for a site which already harbours a mini-grid). Typically, when screening sites for mini-grid deployment based on an initial geospatial assessment and desk research, a range of criteria are used which often includes population density and the level of commercial and economic activity. These criteria are used to develop a ranking of the most promising sites. The criteria tend to be correlated with levels of productive activity and therefore the site screening process becomes an implicit screening process for viable PUE sites as well. The above geospatial mapping tools and survey dataset may also be used as well.

The data for site screening may be obtained from desk research (e.g. geospatial planning tools and open source field data). While some information about commercial activities may be obtained from open-source planning tools, among the tools listed on the Nigeria Off-Grid Solar Knowledge Hub for demand assessment, most do not provide in-depth information about productive use activities. The geospatial planning tools include PUE-relevant information only as “Point of Interest” tags on maps which indicate the presence of productive and social institutions such as schools, markets and commercial buildings.

The main information identifiable is often the existence of such activities, and not their prevalence, energy requirements, and other crucial information. Only the open access PeopleSuN survey dataset contains more substantive information at the enterprise level, but the dataset is limited in geographical scope and number of respondents (5 enterprises for each of the 225 enumeration areas across only 12 states and 3 geopolitical zones in Nigeria). In addition, none of these tools map agro-processing establishments (which are often the area of PUE activity that developers and donors are most interested in targeting) specifically.

| Tool | PUE-relevant Data | Geographical Scope | Comment |

| NOMAP database board | Shops/markets, commercial buildings and industrial buildings (as well as public facilities such as hospitals, schools and universities) | 10 Nigerian states (Abia, Anambra, Bauchi, Edo, Kaduna, Kano, Kwara, Nasarawa, Ondo, and Oyo states) | - |

| Nigeria Integrated Energy Planning Tool | Banks, business services, education facilities, health centers, basic health centre, clinic, dispensary, and seven other types of healthcare facilities | Entire country | Gives users data on number of establishments for each point of interest per state; but only 37 communities per state have community-level POI information |

| Energy Access Explorer (EAE) | Schools, healthcare facilities and markets; asset ownership (Fan, freezer, refrigerator, satellite dish, smart phone, radio, mobile phone (other), television, and stove) | Entire country | Information on these facilities/institutions and appliance ownership is limited to a few locations. |

| PeopleSuN Survey Data | Enterprise vehicle ownership, enterprise bank account ownership status, enterprise access to informal savings groups, sources of credit/loans, sources of electricity, sources of lighting, ownership of appliances, ownership of high-powered machinery, access to loans for purchase of equipment and appliances, monthly expense on fuel, sufficiency of electricity and sufficiency of equipment. | Survey data from 1,122 enterprises across 3 geopolitical zones (North West, North Central and South South) and 75 enumeration areas per zone, across 12 states. Survey covered 5 enterprises per enumeration area. | - |

| REA Database | Mines, schools and water points | Entire country | Very limited appearance of the points of interest |

| Nigeria SE4ALL Platform | None | - | - |

Site Survey

Once the site screening process produces a ranking of the most viable sites, site surveys are deployed to obtain community-level information relevant to mini-grid installation and operation. Mini-grid site surveys typically include questions about the number of enterprises by activity, which is relevant for PUE assessment. However, additional questions to aid PUE assessment may be included within the general site survey (if the survey will be administered to a gathering of key community stakeholders) or a more in-depth productive use survey may be developed and administered to a sample of productive use actors.

The PUE survey should contain questions that elicit data needed to address the following:

- Number of productive users by sector and activity

- Volume of processed output by activity and presence of nearby markets

- Activities where electric equipment are most viable for use

- Productive activities with the greatest actual and potential use of electricity

- Sources of financing for PUE equipment

- Financial capacity of productive users of electricity

- Availability of technology providers

- Technical capacity (and training needs) of prospective productive users of electricity

- Other relevant factors affecting PUE demand, supply, skills, finance, etc.

Since solar powered irrigation systems (SPIS) are one of the most popular PUE technologies, a comprehensive data collection and assessment toolkit exists. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and GIZ have published a Toolbox on Solar Powered Irrigation Systems (SPIS) which includes a Site Data Collection Template. The questions in the template may be adapted to other PUE technologies. Additional questions of relevance for a site survey may be found in the EUEI PDF and GIZ (2011: 48-49) Productive Use of Energy – PRODUSE Manual. The toolbox may also be adapted to other PUE technologies.

PUE Assessment

The Power Africa Nigeria Power Sector Programme (NPSP) has pioneered a robust approach to conducting PUE feasibility assessments, which may further be combined with the FAO-GIZ Toolbox (GIZ & FAO, 2018).

| Tool | Description |

| Toolbox on Solar Powered Irrigation Systems (GIZ & FAO, 2018) | Describes in detail the available configurations and individual system components of a Solar Powered Irrigation System (SPIS) operating under constantly varying conditions due to daily and seasonal fluctuations. |

| Agricultural Productive Use Stimulation in Nigeria: Value Chain & Mini-Grid Feasibility Study (Power Africa, 2020) | Describes an approach to rating activities based on readiness for electrification, conducting value chain analysis, processor cash flow analysis, impact on mini-grid economics, business model options, |

| Productive Use Solar Irrigation Systems in Nigeria (Power Africa, 2022) | Describes solar irrigation cost-affecting factors, value chain analysis, business models, financing options, and business case scenario analysis. |

| Productive-Use Methodology for Evaluations (A2EI, 2020) | Describes a PUE evaluation approach. |

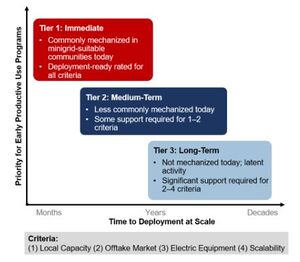

The NPSP approach is to evaluate the potential of value chain activities for electrification (via mini-grids) for each activity and/or crop across four dimensions:

- Existing local capacity for the activity

- Presence of a market for the product

- Availability of electric processing equipment in Nigeria, and

- Scalability of the activity

Based on these factors, prospective productive use activities can be divided into three tiers based on their readiness for electrification and implementation (Figure 2).

Tier 1 activities are viable for immediate electrification with some support for financing and procurement (Power Africa, 2020: 12). They emphasize crops with high-volume production, an active appliance market, and which are typically mechanically processed before local market sale.

Tier 2 activities are viable for medium-term electrification since they require going beyond support for financing and procurement and including supports such as enabling offtake, developing suitable appliances, or building local capacity (Power Africa, 2020: 12).

Tier 3 activities have the potential, in the long-term, for electrification, and require more robust support to realize. It includes the latent activities that could feasibly make use of electricity if robust support is provided to build adequate local capacity, market linkages, and supply minigrid-compatible equipment from the ground up (Power Africa, 2020: 2).

Activities/crops and equipment appropriate for those activities/crops are then rated according to the tiers (Figure 3).

Business Case Scenario Analysis

For each of the Tier 1 activities/technologies, business case scenario analyses may be conducted to assess the economic viability of each PUE technology for each state or cluster of communities, across various business models. Key outcomes of interest for these scenario models to produce are expected yield, profitability, and repayment outcomes. Key variables include crop type, cost of the PUE technology, size of the technology (i.e. its energy consumption), ownership models and base financing structure.

The financial outcomes for the PUE equipment user may be modeled with the FAO-GIZ INVEST Payback Tool. This Excel-based tool allows the modeler to project internal rate of return (IRR), Net Present Value (NPV) accumulated cash flow, system life cycle costs, years of payback, and yearly loan repayment over 25 years for the farmer who purchases the PUE equipment, based on assumptions made about the equipment initial capital costs and running costs (including electricity costs), lifespan of each equipment component, loan amount, interest rate, loan tenor, subsidy value, inflation, profit margins, etc.

Certain assumptions may be obtained from other data sources (e.g., inflation rate from the National Bureau of Statistics; and equipment cost assumptions from the literature or catalogues of market prices for the equipment), while assumptions such as total maximum water pumped per day (for a solar irrigation system) and gross farm profit per year may be calculated using the SAFEGUARD WATER - Water Requirement Tool and the INVEST - Farm Analysis Tool, respectively.

Impact on Mini-Grid Economics

In the case of a mini grid-tied PUE project, the impact of introducing PUE equipment on the mini-grid system and its economic viability is often a crucial consideration for the viability of PUE technologies. This may be simulated with mini-grid technical and financial modeling software such as HOMER Pro. Relevant data inputs include the load profiles of the PUE equipment (and various scenarios with differing numbers of PUE equipment), with assumptions made about the sizing, costs and utilization factor of the mini-grid system. The load profile data may be obtained from desk research.

Business Models for PUE Deployment

Priority business models for Tier 1 and Tier 2 activities may be identified, which refers to the types of arrangement by which the viable PUE technologies may best be deployed. The Facilitator Model requires that a facilitator enables small-scale processors to invest in equipment by serving as their education resource and connection point to finance providers, which includes building awareness about the investment opportunity and providing business development training to support loan applications (Power Africa, 2020: 26).

The Processing Center Model, on the other hand, requires the mini-grid developer to invest in, own, and operate the equipment for a new processing service which are not provided by existing entrepreneurs. The mini-grid developer takes on the credit and operational risk, unlike the facilitator model whereby the third party facilitator takes on these risks. The model is suitable for activities where a product has proven demand, but the activity is not prevalent in the community.

Business Models for PUE Equipment Users

In terms of the PUE equipment prospective users, there are various ownership models which may be utilized. These include the Supplier, Lease-to-own, Equity-cum-subsidy, Pay-as-you-go (PAYG), Out-grower, Shared, Group Sharing, Renting, and Water-as-a-service models (Power Africa, 2020: 32-36). Each model has advantages and disadvantages. The choice of business model depends on the availability of suppliers providing such financing arrangements, the income levels of potential PUE equipment users, the availability of user cooperatives with the capacity to adopt the group sharing model, and other key considerations.

Training Needs

Tier 1 and Tier 2 activities may require PUE equipment users to undergo training. In many cases, a PUE technology provider installs the equipment and demonstrates how it may be used. The product typically comes with installation manuals and warranties. However, in some cases, more substantive training may be required. Examples of aspects of a productive use training curriculum for end-users may be gleaned from the Nigerian Rural Electrification Agency which, as part of its Component 2 of the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP), developed a training curriculum for mini-grid end-users that includes the following:

- Productive Use of Energy: End users are trained on new strategies to increase income whilst using energy more efficiently.

- Enterprise Development (ED): This consists of entrepreneurship classes with an aim to develop the business skills of end-users in the rural areas.

- Financial Literacy: End-users are trained on basic finance skills such as book-keeping and maintaining positive cash flow to boost their creditworthiness.

- Technical Literacy: End users undergo practical tutorials where they will be instructed on operation and maintenance processes regarding technical aspects of productive use appliances.

Bibliography

A2EI (2020). Productive-Use Methodology for Evaluations. https://a2ei.org/resources/uploads/2020/10/A2EI-Productive-Use-Methodology-Webinar-Presentation-October-13-2020.pdf.

CrossBoundary (2020). Study Design: Appliance Financing 3.0 Energy-Efficient Productive Use 2020. Nairobi: CrossBoundary LLC. https://crossboundary.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/CrossBoundary-Innovation-Lab-Study-Design-Appliance-Financing-3.0-Energy-Efficient-PU-2020.pdf.

EUEI PDF & GIZ (2011). Productive Use of Energy – PRODUSE: A Manual for Electrifi cation Practitioners. Eschborn, Germany: European Union Energy Initiative Partnership Dialogue Facility (EUEI PDF) and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). https://energypedia.info/images/9/92/EUEI_PDF_ProductiveUseElectricityManual.pdf.

GIZ & FAO (2018). Toolbox on SPIS. Energypedia.

Power Africa (2020). Agricultural Productive Use Stimulation in Nigeria: Value Chain & Mini-Grid Feasibility Study. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00WQX4.pdf.

Power Africa (2022). Productive Use Solar Irrigation Systems in Nigeria. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00Z9P4.pdf.

Rural Electrification Agency (2020). Terms of Reference for the Engagement of a Consultant to Undertake Trainings on Productive Use of Energy. Abuja, FCT: REA. https://rea.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Training-on-Productive-Use-ToR.pdf.