Biomass Briquettes – Production and Marketing

Basics | Policy Advice | Planning | Designing and Implementing (ICS Supply)| Technologies and Practices | Designing and Implementing (Woodfuel Supply)| Climate Change

Overview

Biomass, as a renewable energy source, has started to look much more favourable again in recent years. There are many reasons for this trend, ranging from increased socio-political discussion on our future energy supply to technological progress. The latter, in particular, has helped change the image of biomass: while fewer regard it as old fashioned, expensive or even dirty, today biomass raise its profile as a renewable and profitable energy carrier. New processing methods have even improved the fuel and handling characteristics of biogenic fuels. Those that have made the biggest difference are briquetting and pelletization, from the solid fuel industry. Both of these techniques are based on compacting the original loose material to yield one basic advantage: a higher energy densification. Hereinafter the term briquetting will be used for both products briquettes and pellets. To understand the difference, see following chapter “Why to briquette”.

The advantages of biomass briquetting are by no means limited to its use in modern industrial plants or solid fuel boilers. Indeed, in developing countries a far bigger percentage of the population cover their energy needs with biomass alone, where their primary need is for heat energy for cooking and heating. International development cooperation has accordingly long been focussed on improving the basic energy supply in many countries around the world. It is notable that biomass briquettes have played a bigger part in many projects over recent years, such as those for distributing better stove technologies, for example. Next to adapted cooking behaviours and improved cooking appliances, the fuel can play one important role in improving the overall situation of households. Biomass briquettes can be produced out of many field or process residues and burning them in cooking appliances instead of traditional fuels as logged and collected wood or charcoal can be an interesting alternative for business makers but also for fuel clients. However, like for most new technologies, many technological but also economical questions may arise. This article will not answer to all questions but should rather help to ask the right ones. The following pages address persons who are interested in the theme of briquetting and who might have thought about: what to concern when starting a business or support business development with biomass briquettes? The aim is to provide an overview of the main findings about biomass briquettes as fuel. But, this article should not be a final version but rather a “living document”: everybody who posses experiences with biomass briquetting is welcome to add information and to share discussion with other readers of this article.

Why to briquette biomass?

“In order to understand where we are with our energy resources and consumption patterns today, it's worth taking a look back at how human energy use has changed over time.”[1]

Let’s start with a short look back: the history of human energy use is shaped by energy densification! For thousands of years, biomass was almost the only constant available and controllable energy source. Wood served as the preeminent form of energy until the mid- to late-1800s, even though water and wind mills were important to some early industrial growth. Coal became dominant in the late 19th century before being overtaken by petroleum products in the middle of the last century, a time when natural gas usage also raised quickly[2]. Thus, the energy content per unit (mass or volume) of the resources increased steadily.

Almost all forms of energy, fossil fuels, wind or biomass, were or are driven by solar energy. When managed sustainable, i.e. harvest does not exceed growth, biomass is a renewable energy. Through the mechanism of photosynthesis solar energy is bound into chemical energy in the plants. Thereby it gets usable for humans in form of eating or burning.

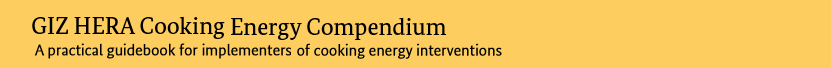

Briquetting or pelletizing is the process to improve the characteristics of biomass as a renewable energy resource by densification. Densification means less volume needed for the same amount of energy output. Figure 1 visualises the magnitude of the differences of bulk density. Each column has the same energy content and represents the volume needed to obtain the equivalent energy of one litre of fossil heating oil. Wood pellets have the highest energy content per volume within the solid biomass examples here listed.

Figure 1: Energy per volume of renewable resources compared to fossil oil and coal[3]

The advantages of processing and densifying of biomass are not only limited to the higher energy content. Both of the techniques, briquetting and pelletizing, are based on compacting the raw material to yield certain advantages[4]:

- High volumetric energy density

- Favourable dosing characteristics

- Lower water content in the fuel and therefore greater storage stability (less biodegradation)

- Option to use additives to change the chemical/material properties

- Less dust produced when handling

- High homogeneity of the fuel

For the European market, the differences of briquettes and pellets is listed in the European classification standard CEN/TS 14 961. For both products, different parameters as shapes and sizes are exactly predefined. In the context of developing countries these definitions might be much too strict. Pellets are small round rods whereas briquettes are bigger and can show different forms. So in a broader context, pellets might be described as a bulk material whereas briquettes can be stacked.

Figure 2: Pellets and briquettes [own pictures]

|

A comparison of mass and volumetric energy contents of different fuels can be found here. (accessed 16/02/2014).

The raw material

„If you can shovel it then you can briquette it[5]”

The raw material is always the beginning of each value chain for processed products. Therefore, before starting to briquette, the main questions are: what to briquette and how to get the raw material. Basically, each kind of biomass might be used for the production of biomass briquettes as a fuel. The mentioned quotation above from S. Eriksson and Michael Prior illustrates in a very simple way the huge theoretical potential of raw material. However, it also contains an important requirement for the biomass: it should be dry!

It is rare that energy plants are cultivated and grown for the only purpose of a later briquetting. Moreover, briquetting is applied to improve the quality of an original fuel material and thereby add value to a poor quality product, mainly agro-residues. Briquetting biomass-residues is one way to solve a problem: how to put the huge volume of wastes from agricultural and agro-processing to some useful purpose. The following picture illustrates the wide range of raw material used for briquetting.

Figure 3: Samples of biomass briquettes from all over the world[6]

It is sometimes assumed that residues are wastes and therefore “free” almost by definition. In practice,it is unwise to assume that any residue is “free” in the sense that it has no alternative use of some value. Thus inevitably in a monetized economy, everything which has a use acquires a monetary value. This is most obvious in the case of fully commercial briquetting plants based upon processing residues or wood-wastes. It is difficult to find examples of operating briquetting plants which do not have to pay something for the residues they use. Such payments may arise because there are competing uses for the “waste” but it may also arise simply because a residue provider is unwilling to allow someone else to make profit from their wastes without asking for a share in the form of payment for the raw material. In general we can distinguish field or processed residues.

Field residues

International and regional statistics (see: http://faostat.fao.org/) often demonstrate the immense quantities of field residues. Most residues are dry at the moment of harvesting and therefore a high potential raw material for briquetting. The volume of residues produced per unit of cultivation is within a wide range, depending strongly on the crop, the intensity of agriculture and climate. However, the recovery rate would be lowered by alternative uses for the residue, though important, uses by local people. These could include animal feed and bedding, direct use as fuel and various building material. In addition, the ploughing in or burning of residues play an important part in promoting soil fertility. Apart of these alternative uses, some additional economical issues should be considered, especially when thinking of briquetting of field residues:

- The access to a sufficient quantity of raw material to run the briquetting machine economically.

- Seasonal transport and storage capacities.

The following two example calculations help to understand the importance of these aspects for briquetting of field residues:

Land Needs

To demonstrate the important role of the volume of residues for a briquetting plant, a very simple calculation might help: assuming a specific recovered residue value of 3 tons per hectare, as well as a briquetting machine with a production capacity of 300 kg per hour; furthermore for an economical output of the briquetting machine we assume that it will run for 8 hours a day for half a year. These presumptions result in a necessary access to 146 hectares of cultivated land!

Transport and storage

In general, field residues are bulky; baled wheat straw has been put at around 100 kg/m3 and stacked cotton residues at 55 kg/m3. Even when chipped, cotton residues only have a bulk density of 130 kg/m3. By contrast, stacked wood has a bulk density above 500 kg/m3. This means that the transport of residues to a briquetting plant can become increasingly expensive as the distance from the site of the residues to the plant increases. In addition, most field residues appear only for a given period in the year requiring seasonal transport capacities (tractors, trailers etc.) and storage capacities. Coming back to the above mentioned example calculation: there would be the need to transport almost 440 tons of raw material in few days and, assuming baled straw wheat, a storage room of 4400 m3, which could be a building with an outline of 30 x 30 meters and 5 meters of height.

Process residues

In this category, all residues obtained from the processing of a crop or wood are included, for example: coffee husks, groundnut shells, rice husks, coir dust, sawdust, furniture waste etc. In principle, the briquetting process works quite well for a wide range of feedstocks provided they are homogeneous and contain moisture below 15 %.

In general, the evaluation of a plant based upon process residues is less complex than for one based on field wastes. The main problem is to establish the quantitative availability of material from a limited number of point sources, possibly only one. This is inherently simpler than to establish the potential residue yields from shifting agricultural patterns of several outside farms. In effect, the transport costs of gathering, which can be the main barrier to utilization of crop residues, have been absorbed by the transport of the valuable food-component of the crop.

At the other extreme, a briquettor tied to a particular process residue from a single plant may find itself stranded if the supply of residues fails to meet expectations as the plant itself fails to find any raw material. Changes in agricultural practices or simple miscalculation can lead to that the feed-plants simply cannot deliver enough residues. The small value of the briquettes relative to the total value of the crop means that the issue of providing briquetting raw-material was irrelevant to the wider agricultural changes going on.

|

Production of biomass briquettes

„The Art of Briquetting [7]“

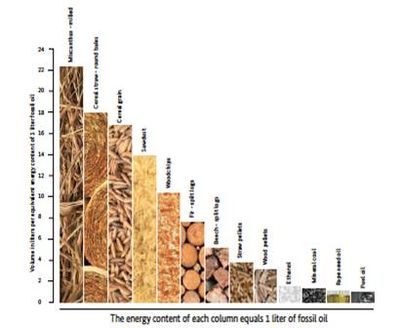

The reduction of material density is the reason for undertaking briquetting as it determines both the savings in transport and handling costs and any improvement in combustion over the original material: the art of briquetting. This art essentially involves two parts: the compaction under pressure of loose material to reduce its volume and to agglomerate the material so that the product remains in the compressed state. Later effect, the cohesion of the particles, is based on three main mechanisms[8]:

- Generating a positive coupling of particles by fibre connections

- Attraction forces between particles through hydrogen bonds

- Creating of form-closed bonds through the sticking effect of several biomass contents (lignin, protein, starch) or added binders

Figure 4: Binding mechanisms[9]

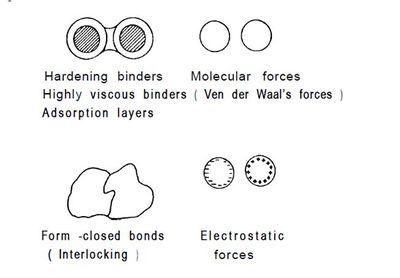

A binding agent is necessary to prevent the compressed material from springing back and eventually returning to its original form. This agent can either be added to the process or, when compressing ligneous material, be part of the material itself in form of lignin. Ligning is a constituent in most agricultural residues. It can be defined as the thermo plastic polymer, which begins to soften at temperatures above 100°C and is flowing at higher temperatures. The softening of lignin and its subsequent cooling while the material is still under pressure is the key factor in high pressure briquetting. It is a physic-chemical process related largely to the temperature reached in the briquetting process and the amount of lignin in the original material. The temperature in many machines is closely related to the pressure though in some, external heat is applied.

Figure 5: arrangement of cellulose, hemicellulose and ligning in biomass matrix[10]

In general there are two immediate ways of classifying briquetting processes. One distinction is whether or not an external binding agent must be added to agglomerate the compressed material. The second way of classifying follows the pressure applied while briquetting: high, medium or low pressure. For a rough distinction the following numbers might be adopted:

- Low pressure up to 5 MPa

- Medium pressure 5 – 100 MPa

- High pressure above 100 MPa

Usually high pressure processes will release sufficient lignin to agglomerate the briquette. Medium pressure machines may or may not require binders, depending upon the raw material whilst low-pressure machines invariably require binders. Such external binders might be: starch, clay, molasses or wood tar etc.. All briquettes using inherent binders (lignin) or external hydrophilic binders (starch, molasses, gum, clay) are not waterproof and will disintegrate when they come into contact with water or stored under humid conditions.

Briquetting of charcoal

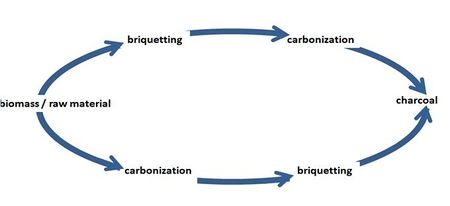

Charcoal is produced in many countries around the world. The basic idea is quite similar to briquetting: the densification of energy. Therefore, biomass is pyrolized in kilns by a controlled burning process lacking sufficient oxygen for a complete burning of the raw material. Briquetting can be combined with carbonization to further improve the densification of the charcoal. Basically the two processes can be applied one after the other:

Figure 6: from biomass to charcoal [own illustration]

But, during the carbonization process, the biomass is losing its lignin content and thereby an important binder for briquetting. Charcoal is a material totally lacking plasticity and hence needs addition of a sticking or agglomerating material to enable a briquette to be formed. The binder should preferably be combustible, though a non-combustible binder effective at low concentrations can be suitable.

Further information:

- “Charcoal Production from Alternative Feedstocks” by NL Agency (2013) provides a good overview on charcoal production technologies, on carbonization of biomass and suitable binders including the description of three supply chains presented as case studies. production from alternative feedstocks - June 2013.pdf http://english.rvo.nl/sites/default/files/2013/11/Charcoal production from alternative feedstocks - June 2013.pdf

Briquetting technologies

Industrial methods of briquetting date back to the second part the the 19th century. Since then there has been widespread use of briquettes made from brown coal, peat and coal fines. The briquetting of organic materials requires higher pressure as additional force is needed to overcome the natural springiness of these materials. Essentially, this involves the destruction of the cell walls through some combination of pressure and heat. The following overview presents the most common machines used for briquetting biomass.

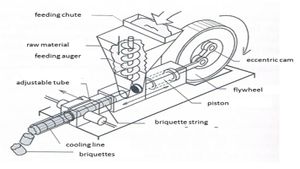

Piston presses:

In piston presses, pressure is applied discontinuously by the action of a piston on material packed into a cylinder. They may have a mechanical coupling and fly wheel or utilize hydraulic action on the piston. The incoming raw material is pressed against the compacted material inside the pressing tube and leaves the die in the rhythm of the piston action. Through pressure and friction forces inside the pressing tube, the material is strongly heated and cooling mechanisms might be considered. To produce briquettes with high density (up to 1.25 g/m3) the raw material eventually needs to be milled (less than 10 mm) and dried (<15% of water content) before briquetting. The capacity of piston presses depends both on the diameter of the die and the pretreatment of the raw material.

The capacity spectrum of piston presses range from only 25 up to 1800 kg/hr. Their typical specific energy use requires between 50 and 70 kWh/t.[11]

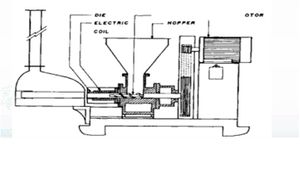

Figure 7: piston presses[12]

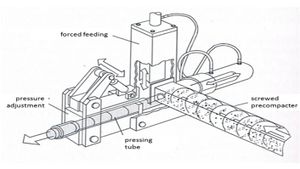

Screw compaction or Extrusion

The aim of compaction using an extruder is to bring the smaller particles closer so that the forces acting between them become stronger, providing more strength the densified bulk material. During extrusion, the material moves from the feed port, with the help of a rotating screw, through the barrel and against a die, resulting in significant pressure gradient and friction due to biomass shearing. The combined effects of wall friction at the barrel, internal friction in the material, and high rotational speed of the screw, increase the temperature in the closed system and heat the biomass. This heated biomass is forced through the extrusion die to form the briquettes with the required shape. If the heat generated within the system is not sufficient for the material to reach a pseudo-plastic state for smooth extrusion, external heat might be added. In principle, screw presses reach slightly higher compaction but lower capacity (tons per hour) when compared to piston presses.

Figure 8: screw presses [left image[13]; right image[14]]

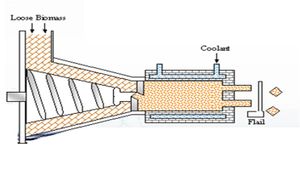

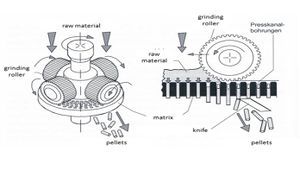

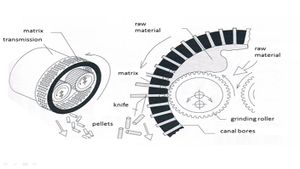

Pan grinder presses for pelletizing

Pellets are the result of a process which is closely related to the briquetting processes described above. The main difference is that the dies have smaller diameters and each machine has a number of dies arranged as holes bored in a thick steel disk or ring. The material is forced into the dies by means of rollers moving over the surface on which the raw material is distributed. The pressure is built up by the compression of this layer of material as the roller moves perpendicular to the centerline of the dies. Thus the main force applied results in shear stresses in the material. The pellets will still be hot when leaving the dies, where they are cut to lengths normally about one or two times the diameter. Successful operation demands that a rather elaborate cooling system is arranged after the densification process.

There are two main types of pellet presses: flat and ring types. The flat die type has a circular perforated disk on which rollers rotate whereas the ring die press features a rotating perforated ring on which rollers press on the inner perimeter. The output of pellet presses range from about 200 kg/hr up to 8 ton/hr. Their specific energy consumption is reported to be around 1,5% of the energy content of the final peletts[15].

Figure 9: pan grinders[16]

Manual

For sure the simplest way to produce small briquettes is hand-shaped briquettes: a slurry of biomass in water is left soaking for some days to enhance binding properties. The pulp is either squeezed by hand or pressed into a mould e.g. an ice-cube tray. Rearranged fibres assisted by a binder like paper pulp keep the briquette in shape during drying and use. A part of hand-shaped briquettes there are plenty of small manual briquetting machines which were developed by different producers and scientists all over the world. A very good overview on existing low cost briquetting machines, from perforated bottles to wooden lever presses, can be found in the manual “Micro-gasification: Cooking with gas from biomass” by Christa Roth (2011)[17].

Figure 10: examples of low cost briquetting machines[18]

However, it remains unclear, whether any manual densification process can ever be commercially viable even in circumstances where labour is very cheap. Considering their very low throughput, such techniques often require almost as much capital investment as the mechanical processes. The savings achieved are essentially a labour for electricity substitution rather than labour for capital.

Roller Presses

Densification of biomass using roller presses works on the principle of pressure and agglomeration, where pressure is applied between two counter-rotating rolls. Ground biomass, when forced through the gap between the two rollers, is pressed into a die, or small pockets, forming the densified product. Roller presses are considered the world standard technology to produce ovoid (pillow-shaped) charcoal briquettes from a variety of biomass types. In a roller press, a mixture of charcoal and binder is fed to the tangential pockets of two rollers to produce briquettes. The smooth production of charcoal briquettes using this technology requires high-quality rollers with smooth surfaces on which the briquettes are shaped. The type of roller determines the shape of the briquettes. Currently, roll presses available in developed countries have production capacities of 1 t/hr and more. The 1 tonne/hr capacity press with controlled feeding device costs about $ 320,000. Much cheaper roller-type charcoal briquetting machines can be sourced in India and China: Seboka (2009) indicates that a roller press with a capacity of 1.5 tonne/hr costing $ 19,000 can be found in India[19].

Figure 11: roller presses[20]

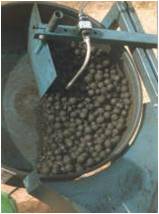

Agglomeration

Agglomeration is a method of increasing particle size by gluing powder particles together. Usually the equipment consists of a rotating volume that is filled with balls of varying sizes and fed with powder and often a binder. The rotation of the agglomerator results in centrifugal, gravitational and frictional forces from the smooth rolling balls. These forces, together with inertial forces, press the balls against the powder, helping them to stick together and grow. NL Agency[21] reports applied agglomeration technology in small-scale briquetting processes in several developing countries. The charcoal is milled to powder, binders are added, the components are mixed together, and the mix is then agglomerated. Agglomerated charcoal briquettes are produced using a motor-driven agglomerator, the typical nominal capacity of which is 25-50 kg/hour. Agglomerated charcoal briquettes are spherical and typically have diameters between 20-30 mm. The briquettes can be used for household cooking as well as for fuelling industrial furnaces. Agglomerated briquettes are said to be stronger than most other briquette types (Reference numbered as "5". It is missing and does not match order).

Figure 12: Small-scale agglomerator[22]

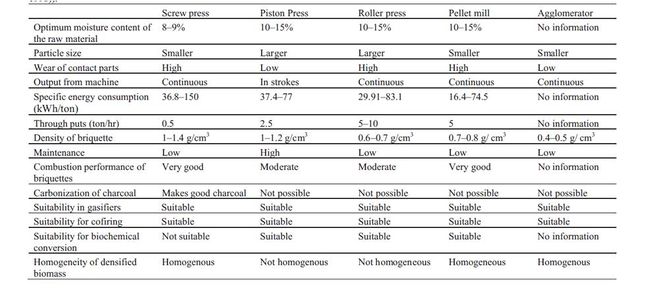

As seen above, there are different technologies to produce densified biomass briquettes. The following table 1 summarizes their main characteristics. For the right choice of an adapted machine, two main issues should be considered:

- Quantity and quality of the raw material

- Market availability of briquetting machines and spare parts

Table 1: Comparision of different densification equipments[23]

Problems arise often if the die has not been shaped correctly or if the feeding mechanism has not been sized for the material to be used. It is normal for machines made in Europe or North America to be designed to operate on wood wastes. The use of agroresidues normally de-rates the throughput and may require some modification to the feeder. Therefore, when searching for briquetting machines, best is finding machines which are already running with similar raw material and under similar conditions.

Further information:

- Bhattacharya, S.C.: biomass energy and densification: A Global Review with Emphasis on Developing Countries; Energy Program, Asian Institute of Technology; Thailand gives an overview on different technologies used for briquetting in many countries in Asia, South America and Africa. Link: http://cenbio.iee.usp.br/download/documentos/apresentacoes/swedendensificationpaperfinal.pdf

- When searching for “briquetting” in the internet a huge number of producers will appear. A list of mainly European briquetting machines sellers can be found under http://www.tfz.bayern.de/mam/cms08/festbrennstoffe/dateien/pelletier_briketiertechologie.pdf.

Auxiliary equipment

Only in few cases will the briquetting press be the only equipment needed to set up a briquetting plant. From the starting point, the complexity of briquetting plants increases up to the fully automated woodwaste briquetting plants in which the raw material is fed by a tractor into a hopper from where it is crushed, screened, stored, dryed, stored again, fed into the presses and transported to the product storage in fully automatic process, supervised by a couple of operators. Without going into details, the following text is a brief listing of a few common types of necessary auxiliary equipments and their applications which might have to be considered as also important economical factors:

- Storage (rainy seasons, both the raw material and the product)

- Handling (conveyors, elevators etc.)

- Comminution (chipper, hammer mill, conditioner, mixing with binder)

- Classification (separation, cleaning)

- Drying

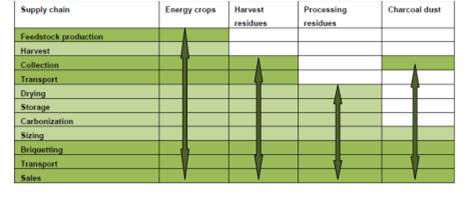

To demonstrate the necessary steps for charcoal briquetting of different raw materials, NL Agency (2013) created table 2 below. Charcoal dust has the shortest supply chain, only a collection and briquetting step is needed to produce charcoal briquettes. On the contrary, the charcoal production chain based on the growing of dedicated energy crops involves a considerable number of steps. Each step in the supply chain represents efforts, money and possible complications, and this indicator shows that charcoal dust and processing residues have a logistic advantage over other types of feedstocks.

Table 2: Charcoal production chain of selected feedstocks[24]

Costs

The financial costs of briquetting are very dependent upon the nature of the project, in particular upon the raw material used and the plant location. They depend upon a number of operating costs, including labour, maintenance, power, raw material cost and transport etc. as well as of capital cost component. Whether or not briquetting is economic in any given location will depend critically upon how these unit costs relate to the price of the likely substitute fuels.

Capital costs

The capital costs of a plant are not always easy to establish on a consistent basis. In different circumstances there may be different conventions about what is included in capital cost: for example, do spare parts count for capital costs or operational cost? Is the plant a stand-alone operation or is it part of an existing agro plant and maybe existing buildings can be used?

Probably, one of the biggest variations in plant capital costs, however, comes from the raw material to be used and the form in which it is collected. The nature of the raw material, especially the density, influences significantly the output rate of briquetting machines. Most agro-residues will cause lower outputs than wood residues for the same briquetting machine what will influence the unit capital costs. In addition, the form of the initial feed may require pretreatment efforts before it is fed to the briquetter as such. Some wastes, for example sawdust, often need to be dried to reduce their moisture to 15%, others like cotton stalks might be chipped or shredder before briquetting. Thirdly, there is a very big difference between field-residues and factory-residues if the cost of the equipment to collect the residue is included in the initial capital cost.

Another important aspect of capital costs are the engineering and design standards of the plant. For example, it is likely that in a plant where little or no use is made of mechanical handling, there will be a need to have spacious buildings to avoid problems of dust and dangerous overcrowding. Briquetting machines which are squeezed into residue-producing plants to utilize existing buildings may naturally have lower capital costs than briquetting plants with firm floors, proper electrical fittings etc.

Apart of these direct production capital costs, in many countries additional costs have to be considered and can range widely from country to country. For example credit costs or custom duties on imported machines.

Operating costs

The first obvious operating cost is the price to be paid for the raw material. This costs are very project and site-specific. The raw material might have a specific price when its use is competing with alternative uses. However, even if the residue is free, it is common for a transport cost to be incurred in bringing the residue to the briquetting plant. In the case of briquetting plants sited at the residue production point this is avoided but for other situations the transport cost may be a significant part of operational costs. These transport costs may be added into general labour costs if fulltime drivers are employed but certainly a more common situation is to hire appropriate transport for a given period of collecting the raw material.

The labour costs of a briquetting plant are in general very dependent upon plant design: are there any significant residue collection activities; the wage rate of various categories of labour employed (collecting, loading, maintenance, supervision etc.); and the extent to which the unit is integrated with a larger factory which can supply some labour needs on a part-time basis and cover administration costs. However, S. Eriksson and M. Prior[25] results that despite the wide variations in labour costs, briquetting as such is not labour intensive relative to the unit capital costs and the cost of maintenance, power and other consumables. Labour costs seldom exceed 15% of the total and are usually much less.

Maintenance costs can be a significant element of briquette production costs and one that is often underestimated in planning plants. Especially when briquetting machines are working on abrasive materials, such as rice-husks or charcoal, the maintenance cost can be quite high particularly for pan grinder for pelletizing, screw presses and piston presses. It is a factor which may place a continuing reliance on imported spare-parts or in the need to employ virtually an operative on building up spare parts.

Except of manual driven briquetting machines, all other types of briquetting machines require a certain power supply. There is no reason why plants in remote areas should not use diesel generators or use direct drive from diesel or steam engines. But in most cases the briquetting machines are connected to the main electrical power supply: depending on the size and output rate of the machine whether single phase 220V or 3 phases 400V supply is necessary. The specific requirements and consumption of each machine has to be considered in an early state of planning and to be adapted to local circumstances.

Other costs which might have to be considered when operating a briquetting plant are: taxes, insurance, consumables such as lubricating oil, packaging etc.

Box: Comparison between pelleting and briquetting[26]

|

|

Markets and users for briquettes

“Selling a product isn’t as complicated as it’s made out to be. At its most basic, a sales program is defined principally by what you sell, who you sell to, and how you sell.[27]”

The total production costs as the sum of investment and operation costs define the price of each product. But for competitive products with similar use, their comparison prices will decide their success or not on a given market. For briquettes this competitive market means the range of conventional fuels offered. One of the most important characteristics of a fuel is its calorific value, which is the amount of energy per mass it gives off when burned. Although briquettes, as with most solid fuels, are priced by weight or volume, market forces will eventually set the price of each fuel according to its energy content. However, the production cost of briquettes is independent of their calorific value as are the transportation and handling costs. The calorific value can thus be used to calculate the competitiveness of a processed fuel in a given market situation. So one key question must be:

- Does the price per unit of energy at which briquettes are sold compete with the fuels normally used?[28]

The answer to this question is very site specific and depends on local circumstances. But for sure it is a crucial one and should be at least roughly calculated before starting a business with briquetting.

However, even if the calorific value is probably the most important factor, there is a range of other factors, such as ease of handling or burning characteristics, which also influence the market value of briquettes. These characteristics are more users specific: for example a private user who will burn charcoal briquettes for a garden barbecue will probably have different expectations than someone firing an industrial boiler with for example rice-husk briquettes. This observation leads to a second key question for the market success of briquettes:

- Can the particular briquette be burnt satisfactorily in the combustion appliance used by a particular consumer?[29]

Whereas the first key question might be easy to answer by a simple comparison of solid fuel market prices, the second question might imply indirectly the willingness of consumers to alter their normal combustion appliances to suit briquettes. Without a doubt, before not only changing the fuel but also adopting a whole new combustion unit consumers will hesitate. They will ask themselves if briquettes offer any significant advantages, in terms of quality of combustion or in financial advantages that might persuade consumers to spend money on new appliances. But that is not enough: briquettes are also a consumer good. That means consumers must trust in their availability. This aspect might be especially difficult at the beginning of a briquetting activity while searching for penetrating a new market. The likely size of briquette supply relative to the total traditional fuel supply will be small. At these low kinds of penetration, consumers will always be aware of the need to give themselves an alternative source of fuel. This will certainly be true in the early stage of marketing briquettes whether or not, at the later stage, some consumers would have the confidence to commit themselves wholly to briquettes. Thus, briquettes have to be compatible with existing appliances with little or no modification if they are to have any chance of achieving initial market penetration.

A part of these general considerations about the competiveness of briquettes there might be some user specific thoughts. These are discussed in the following by regarding the solid fuel which is supposed to be substituted by briquettes.

Burning appliances

Wood burning appliances

Technically there does not seem to be any major problem about using briquettes in existing cooking or heating appliances which were originally designed for burning wood. Due to the high density of briquettes and their surfaces sometimes problems with initial ignition and heat-raising are reported. But this fact can easily be overcome by co-firing wood at the beginning. It is probably more difficult to sell bigger sized briquettes simply because the physical dimensions of household stoves are limited. Large logs are similarly rejected.The general combustion behavior of biomass briquettes is comparable to wood. Briquettes can therefore normally be used in traditional stoves as a substitute or as co-firing of wood. In fact in many countries briquettes can be found on local markets. Especially for normal households in developing countries the comparative price and the availability of briquettes will play a major role for their acceptance rather than the technical characteristics when burnt in stoves designed for wood.

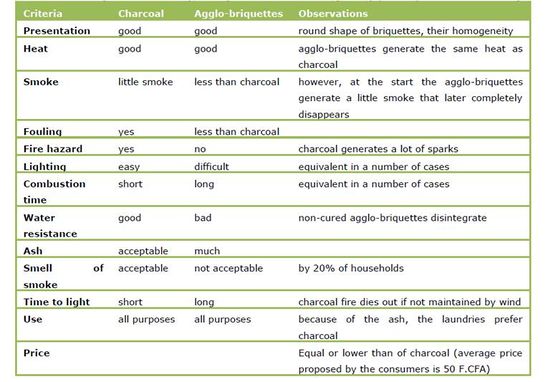

Charcoal burning appliances

Charcoal stoves are often the second important cooking appliance and therefore an important solid fuel market in many developing countries. As shown in the chapter of briquette production there is also the possibility to produce charcoal briquettes out of biomass residues. Practically, these charcoal briquettes can be burnt in stoves designed for normal charcoal. Literature report somehow contradiction results about the user acceptance of charcoal briquettes, something which may be related to the different cooking situations in which the briquettes were used. For example, S. Eriksson and Michael Prior[30] mentions great problems in persuading households in India to burn molasses-bound charcoal briquettes due to complains about smells and about the speed of burning. On the other hand, market research carried out in Sudan on molasses-bound charcoal briquettes made from cotton stalks were said to be an acceptable charcoal substitute. Whereas a NL Agency study[31] reports little success of cotton stalk charcoal briquettes in Mali as summarized in table 1 but very good market sales for coal dust briquettes in Kenya. In general, depending on the raw material and the binders used in the production, charcoal briquettes may show higher ash contents and different burning characteristics when compared to normal charcoal. This fact might be important for the success of charcoal briquettes and user acceptance must be investigated before entering a market.

Table 3: Summary of results acceptability tests[32]

Gasifier stoves

In recent years, more and more efforts in research and introduction of gasifier stoves for households can be observed. In general, the gasification process places higher quality demands on the solid fuel than does combustion. There are a number of important potential advantages of using briquettes instead of for example chipped wood for gasification: the briquettes are drier, increasing the efficiency of the process and increasing the calorific value of the produced gas; the bulk density is higher, increasing the residence time in the gasifier and the gas conversion rate and, finally, the size of the briquettes can be chosen to fit together with the size of the gasifier and the gasifier grate. In general it appears that briquettes can be used to provide a consistent feedstock to most gasification systems and thus show advantages on a market where gasifier stoves are used in households.

Further information:

- “Micro-gasification: Cooking with gas from biomass” by Christa Roth (2011)

The manual provides a detailed description of the gasification process in household stoves and the application of briquettes in these stoves. https://energypedia.info/wiki/File:Micro_Gasification_Cooking_with_gas_from_biomass.pdf

Marketing

All hereby mentioned appliances (wood, charcoal, gasifier stoves) for briquettes are mostly supposed to target two main market segments:

- The mass domestic market, consisting of normal households that use wood or charcoal as daily cooking.

- Business and institutional consumers. This segment includes large consumers such as restaurants, hotels, institutes etc.;

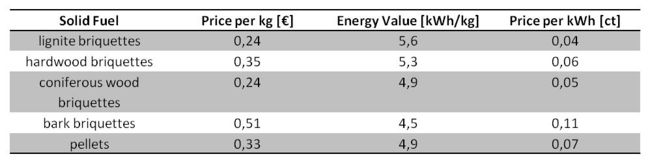

Both of these market segments are driven by consumer decisions which are normally based on price comparisons between biomass briquettes and traditional solid fuels. But not always the price seems to be the only or crucial point for a consumer decision to buy biomass briquettes. This fact can easily be observed when for example comparing solid fuel prices in a German hardware shop: even if prices per energy content are higher, than for example the price for lignite, biomass briquettes are well sold.

Table 4: comparison of solid fuel prices in Germany [own observation]

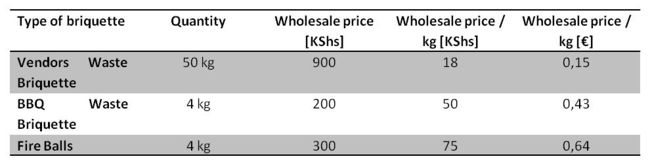

The observation of the willingness to pay a higher price for briquettes are not restricted to industrial countries, whereas examples of niche markets for higher priced briquettes can be found also in developing countries. These might be luxury hotels who want to convey the impression of a sustainable business approach to their clients. Another example is the marketing strategy of the company Chardust Ltd. in Kenya which is addressing three market segments, supplying them with different charcoal briquettes, as follows (Owen, 2012)[33]:

- The business and institutional market is served by lower grade briquettes, marketed as Vendors Waste Briquettes and sold in large bags. These briquettes are made as cheaply as possible in bulk from charcoal dust (fines) with some contamination of soil (clay). No binder is added. The high ash content (due to the clay) cause the briquettes to burn slowly, rendering them particularly for slow-release space heating at night time;

- The mass domestic market is served by regular grade briquettes, made in roller presses and sold in 4 kg bags. As feedstock screened charcoal waste is used, with minimum contamination. Gum Arabic is used as binder. Briquettes are sold by Chardust Ltd. at prices below the urban wholesale price of charcoal.

- Premium grade briquettes targeted at the urban middle class are labelled as Fireballs and sold in fancy packaging in supermarkets. These are made in pan agglomerators from charcoal lumps and a liquid binder (a blend of molasses, corn starch or gum Arabic). This market segment is less price sensitive and fireball briquettes are more expensive than lump charcoal.

Figure 13: marketing example of briquettes in Kenya[34]

Table 5: Price comparison of different briquettes produced by chardust in Kenya

The experiences of Chardust Ltd suggest that in general charcoal dust briquettes have to compete directly on price with wood charcoal. As a result, the (semi-)industrial production of charcoal dust briquettes can only be viable in African countries where charcoal is relatively expensive. Chardust Ltd. roughly calculates that the minimum wholesale prices would have to be some $200 per ton (for packaged charcoal). This rules out many African countries as candidate manufacturing sites. On the other hand in areas with high charcoal prices and sufficient charcoal dust there is a good potential for charcoal dust briquetting. Charcoal briquettes that are higher priced but attractively packaged may still find some customers e.g. those willing to pay more for a product that is produced in a sustainable manner. Such environmentally and socially conscious buyers may include individuals as well as institutions (for the latter it may be a part of their company’s policy).

Innovative packaging is one example of smart marketing of briquettes but for sure not the only one. Depending on the clients to address different approaches could be used. A list of marketing tools to support the sales of briquettes in developing countries is suggested by Legacy Foundation[35]:

- Buyers of large quantities can receive discounts or a gift.

- Some fuel briquettes can be exchanged for the delivery of raw materials.

- Pro-environmental conservationists can be included in marketing briquettes.

- Conducting open air cooking demonstrations (e.g. in market centres)

- Participating in shows and exhibitions

|

Key Questions for a successful briquetting

Why to briquette?

- Why do you want to briquette?

- Does briquetting lead to any improvement of your raw material in terms of energy content, fuel or handling characteristics?

- Is densification the right technology to reach your aims of improving a fuel?

- Do you want to create a new fuel competing with traditional fuels?

The raw material

- To which kind of raw material do you have access?

- Are there any practical experiences with briquetting of this material or do you need to invest in research?

- Do you base your briquette production on “real” residues as raw material or may the use of the raw material compete with other uses of some value?

- Does the quantity of the raw material enable an economic production?

- Can you guarantee the access to the raw material?

- Do you need to organize the transport and storage of the raw material?

The production

- Which total production output do you aim for?

- To which kind of production technologies do you have access?

- Is there any briquetting plant which fits to your quantity of production?

- Do you need to consider any pretreatments of the raw material and therefore invest in further machines?

- Can you calculate your foreseen capital and operational costs?

The market

- Who will be your clients?

- Do briquettes fit to their fuel requirements and to the cooking appliances?

- Do you have access to the fuel market or do you need to build up new selling structures?

- Does the price of your briquettes compete with traditional fuels?

Project Examples

The following examples of biomass briquetting projects are by far not a complete list of biomass briquetting projects in developing countries all over the world. The mentioned examples were chosen during the research for this article. Everybody is welcome to add other or new projects. The goal is to enable interested persons who are thinking about briquetting of biomass to quickly find projects with similar conditions and so to enable an exchange.

Cambodia – SGFE – sustainable green fuel enterprise

SGFE (Sustainable Green Fuel Enterprise) was created in 2008 with the aim of alleviating poverty and reducing deforestation in Cambodia, as well as improving waste management in urban areas, by developing a local economic activity: manufacturing charcoal using organic waste, mostly coconut. SGFE was initiated by the NGOs GERES Cambodia and PSE (Pour un Sourire d’Enfant) through a joint project: PSE added its social commitment to GERES’s environmental and technical expertise. The goal of SGFE as a real social business is to provide long-term employment to its workers so that they can get a regular, secure and fair income. Thus, the economic viability of the business is crucial, and profits are to be shared among the stakeholders and employees, and reinvested in the company’s development. Currently, SGFE employs 16 people who used to work as waste pickers on Phnom Penh’s municipal landfill.

SGFE charbriquette manufacturing begins with the collection of organic waste in and around Phnom Penh through a network of dedicated suppliers. After drying and sifting coconuts and other raw materials, they are efficiently carbonized, crushed and mixed, then shaped into a convenient and efficient size, and finally dried to guarantee high performance. Furthermore, the production process has been modified to be as energy efficient as possible: the kilns used to carbonize the coconut and biomass ensure efficient combustion, reducing the emission of harmful gases and air pollution; and, the energy generated by the carbonization process is recovered and used to increase efficiency.

Sustainable Green Fuel Enterprise is manufacturing two types of products : Premium and Diamond briquettes. Their tubular shape provides better heating properties compared with traditional charcoal, and is perfectly adapted to cookstoves and barbecues.

All char-briquettes are sold on the local market to shops (retailers who further sell them to households) and food businesses (restaurants and street food vendors). Shops and restaurants tend to prefer premium, while interestingly street food vendors choose the higher quality product (diamond) which has a duration of up to 5 hours. This is because households don't need to cook for long time and restaurants, which use a high amount of char-briquettes, prefer the cheaper product, while street food vendors, cook all day with small quantities of char-briquettes and therefore even though the diamond is more expensive, at last it is financially more convenient for them.

The current production rate is at about 40 tons/month (with a growing trend). Regarding our sales capacity, SGFE currently sell the entire production (the demand is higher than what they can produce) and therefore they are planning to expand the production capacity this year.[36]

For further information see:

http://www.sgfe-cambodia.com/about

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4ROiKaTBWw&list=PL8B4A28B72438426C

Kenya – Chardust Ltd.

Chardust Ltd. was founded in 2000 to produce substitutes for charcoal on a commercially sustainable basis. Chardust making use of low-priced raw materials, ample labour supply and a good measure of innovation, set out to produce fuels that could sell directly into traditional charcoal markets and compete head-to-head on both price and quality. Today, daily sales are in excess 7 tonnes.

Chardust's centre of operations is a 2 acre plot in the Lang'ata area of Nairobi. This is the company head office and home of the briquetting operation and Chardust's programme of research and development. Chardust's main product is the Vendor's Waste Briquette - 'VWB'. It is made from charcoal dust and fines that are salvaged from charcoal traders across the city of Nairobi. These briquettes are for space heating and water heating applications, as well as cooking and roasting. VWB is sold to institutional customers such as poultry farms, hotels, lodges and restaurants, as well as to charcoal dealers and individuals for direct sales into the domestic market.

Chardust also produces a premium charcoal briquette made from selected vendors' waste and natural binders. This lower ash product is designed for the domestic barbecue market and is sold mainly through supermarkets within the city of Nairobi.

Finally, in 2010 chardust introduced agglomeration machinery to their production line for the fabrication of spherical briquettes which are called FireBalls. These are also aimed at the urban mid-scale market.

For further information see:

http://www.chardust.com/briquettes/

India – Biomass Urja Kotdwar

This international carbon offset project was initiated by myclimate in 2009. Previously coal was used in the Indian province Uttarakhand as fuel in the brick and iron production. The carbon offset project by myclimate promotes the use of briquettes made of renewable biomass from forest and agricultural waste. In addition, restaurants, temples, schools, and hospitals are supplied with efficient, smokeless cookers.

In India, many millions of tons of biomass waste accumulate annually from forestry and agriculture as well as from industrial production. Due to its low density and the high water content, this waste material cannot be directly processed. The local organization Rural Renewable Urja Solutions Pvt. Ltd. (RRUSPL) now utilizes this waste raw material as fuel. Biomass briquettes are produced, which are then delivered to companies producing brick kiln and rod iron in the states of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh in the north of India. The climate-friendly energy supply is thus replacing coal, a greenhouse gas-intensive fuel, in the kiln and iron production. The briquette machine is already successfully used in many of India and reduces the local population's dependence on fossil fuels.

However, the project not only includes the manufacture of renewable, clean fuel, but also the distribution of an efficient and smokeless cooker (chulha) for restaurants, temple complexes, day schools and hospitals. These rural institutions in India were previously very dependent on liquefied petroleum gas for cooking. The new efficient gas cookers were developed by the Indian Energy and Resource Institute (TERI).

For more information see:

http://www.myclimate.org/klimaschutzprojekte/projekte-international/detail/mycproject/15/95.html

Zambia – Emerging Cooking Solutions (ECS)

Emerging Cooking Solutions is combining the sales of clean cooking stoves with pellets as fuel. ECS introduces to the market a unique cooking-system using an inexpensive, abundant and largely untapped source of energy for cooking:they are (at the moment) using a mix of pine and eucalyptus sawdust and peanutshells. The sawdust is a waste product from local sawmills that get their wood from state owned plantations, no virgin or indigenous trees are touched. ECS has also experimented with a variety of biomass, ricehusks, maize and straw to name a few and will use these at a later stage, but the reason they use sawdust is that it is there, in one place, and is waste. They only wish to use agro- and forestry waste so original forests can be spared, that's their vision. These wastes will be made into pellets. Together with clean-burning, micro-gasifying stoves for homes and restaurants, ECS sells pellets at below market price of the equivalent in charcoal, leading to substantial savings. Today focusing on the Philips stove, but the company is stove-neutral: ECS will provide the best stove for a particular user-group. This can be done at favorable financial terms for the company due to the new product concept and industrialized production and distribution systems. Starting modestly in 2010 with 40 households, ECS, by their own admission, now has the capacity to produce clean, renewable cooking fuel for thousands of households.

During the fall 2013 they made about 30 tons per month. Their equipment can make 5-600 kg per hour, but they haven't had the need to run it full speed yet, since they are a start-up and building a customer base. Their clients are BOP citizens who today use charcoal for cooking, people in townships in Lusaka and Kitwe, and who have no alternative until now.[37]

Further Information

- Alternative Charcoal Tool (ACT)

- The Harvest Fuel Initiative

- The charcoal project

- emerging.se

- climatesolver.org

References

- ↑ Brandi Robinson (2014), Lecturer, College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University: http://bit.ly/1dHM3Li (accessed 16/02/2014)

- ↑ http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=10 (accessed 16/02/2014)

- ↑ Picture: TFZ (2013): Die Energiedichte biogener Energieträger im Vergleich zu Heizöl und Steinkohle. A German comparison of the energy density of different biomass fuels compared to heating oil and fossil coal. http://www.tfz.bayern.de/mam/cms08/festbrennstoffe/dateien/poster_brennstofforgel.pdf (accessed 16/02/2014)

- ↑ The original German version: Kaltschmitt, M.; Hartmann, H. und Hofbauer, H. (2009): Energie aus Biomasse. Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2001, 2009, korrigierter Nachdruck 2009

- ↑ Eriksson, S. and Prior, M. (1990): The briquetting of agricultural wastes for fuel, FAO Environment and Energy Paper 11, FAO of the UN, Rome, 1990

- ↑ Picture: http://www.legacyfound.org/images/photoGallery/briquettesResources/pages/05.html (accessed 16/02/2014)fckLRfckLRfckLRfckLR

- ↑ Advertising slogan of the briquetting company Di piu; www.di-piu.com

- ↑ The original German version: Kaltschmitt, M.; Hartmann, H. und Hofbauer, H. (2009): Energie aus Biomasse. Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2001, 2009, korrigierter Nachdruck 2009

- ↑ Picture : Grover, S.D. and Mishra S.K. (1996): Biomass Briquetting: Technology and Practices; FAO Regional Wood Energy Development Programme in Asia, Bangkok, Thailand (1996)

- ↑ Picture : Jaya Shankar Tumuluru et al. (2010): A Review on Biomass Densification Technologies for Energy Application; Idaho national laboratory; 2010

- ↑ Kaltschmitt, M.; Hartmann, H. und Hofbauer, H. (2009): Energie aus Biomasse. Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2001, 2009, korrigierter Nachdruck 2009

- ↑ Picture: The original German version: Kaltschmitt, M.; Hartmann, H. and Hofbauer, H. (2009): Energie aus Biomasse. Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2001, 2009, korrigierter Nachdruck 2009

- ↑ Picture : http://www.soi.wide.ad.jp/class/20070041/slides/03/index_12.html

- ↑ Picture: Eriksson, S. and Prior, M. (1990): The briquetting of agricultural wastes for fuel, FAO Environment and Energy Paper 11, FAO of the UN, Rome, 1990

- ↑ Kaltschmitt, M.; Hartmann, H. und Hofbauer, H. (2009): Energie aus Biomasse. Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2001, 2009, korrigierter Nachdruck 2009

- ↑ Picture: The original German version: Kaltschmitt, M.; Hartmann, H. und Hofbauer, H. (2009): Energie aus Biomasse. Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2001, 2009, korrigierter Nachdruck 2009

- ↑ https://energypedia.info/wiki/File:Micro_Gasification_Cooking_with_gas_from_biomass.pdf

- ↑ Pictures: http://home.fuse.net/engineering/

- ↑ Seboka, Y. (2009): Charcoal Production: Opportunities and Barriers for Improving Efficiency and Sustainability. In: Bio-carbon Opportunities in Eastern & Southern Africa, UNDP, 2009

- ↑ Picture: Eriksson, S. and Prior, M. (1990): The briquetting of agricultural wastes for fuel, FAO Environment and Energy Paper 11, FAO of the UN, Rome, 1990

- ↑ NL Agency (2013): Charcoal Production from Alternative Feedstocks; final version 2013

- ↑ Picture: NL Agency (2013): Charcoal Production from Alternative Feedstocks; final version 2013

- ↑ Jaya Shankar Tumuluru et al. (2010): A Review on Biomass Densification Technologies for Energy Application; Idaho national laboratory; 2010

- ↑ NL Agency (2013): Charcoal Production from Alternative Feedstocks; final version 2013

- ↑ Eriksson, S. and Prior, M. (1990): The briquetting of agricultural wastes for fuel, FAO Environment and Energy Paper 11, FAO of the UN, Rome, 1990

- ↑ Jaya Shankar Tumuluru et al. (2010): A Review on Biomass Densification Technologies for Energy Application; Idaho national laboratory; 2010

- ↑ http://www.wikihow.com/Sell-a-Product

- ↑ Eriksson, S. and Prior, M. (1990): The briquetting of agricultural wastes for fuel, FAO Environment and Energy Paper 11, FAO of the UN, Rome, 1990

- ↑ http://www.wikihow.com/Sell-a-Product

- ↑ Eriksson, S. and Prior, M. (1990): The briquetting of agricultural wastes for fuel, FAO Environment and Energy Paper 11, FAO of the UN, Rome, 1990

- ↑ NL Agency (2013): Charcoal Production from Alternative Feedstocks; final version 2013

- ↑ NL Agency (2013): Charcoal Production from Alternative Feedstocks; final version 2013

- ↑ Owen quoted in: NL Agency (2013): Charcoal Production from Alternative Feedstocks; final version 2013

- ↑ http://www.chardust.com/briquettes/briquettes/

- ↑ Legacy Foundation: a trainer’s guide for making fuel briquettes; http://www.villagevolunteers.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Fuel-Briquettes-Guide.pdf

- ↑ ---. 2014. "Various e-mail conversations with Carlo Figà Talamanca, SGFE Cambodia, in February 2014"

- ↑ ---. 2014. "Various e-mail conversations with Per Löfberg, ECS Zambia Sweden, in February 2014"