Click here to register!

Result Based Monitoring of Cookstove Projects

=> Back to Overview Compendium

Why monitor?

Projects introduce development changes to make a difference to the lives of target groups. They strive to achieve positive change, and it is essential for them to monitor and evaluate the causal chain from project activity to impacts if they are to prove the value of their project. This information is needed for both project management and for reporting to the outside world (e.g. a partner or donor).

Results Based Monitoring (RBM) serves different purposes:

- To check that set targets have been met

- To provide data and information for reviewing the strategy

- To steer and make changes, where necessary, to an intervention

- To create ownership among various project actors

- To provide evidence on progress/ changes/ achievements for national partners (e.g. ministries).

Results Based Monitoring requires time, personnel and funds, and thus it needs to be included into the activities and budget plan. Ideally, Results Based Monitoring should be planned from the very beginning of a project (concept development, activity planning, budgeting etc.) to ensure that it is an integral part of the approach. Often, however, it is only considered at a later stage. It is important to allocate enough resources (working time, finances) into the budget, and to plan it carefully so that it delivers useful results.

Introduction to Results Based Monitoring (RBM)

Results Based Monitoring is an international monitoring standard developed and agreed by the OECD DAC to monitor development results.

Results chains

The basis of Results Based Monitoring is the results chain, which describes how a development intervention, through a step-by-step process, contributes to development results. The intervention starts with the inputs used to perform activities, and these lead to the outputs of the project. These outputs, which are used by target groups or intermediaries, lead to outcomes and impacts. In most cases, it is relatively easy to attribute changes, up to the level that identifies the uses of the output.

Beyond this, climbing up to the levels of ‘outcome’ and ‘impact’, external factors influence whether the intended results can be achieved. These external factors can only be controlled or influenced to a certain extent (if at all) by the project or programme. Whether the objectives are met no longer depends solely on the performance of the project, but depends on all the actors and external factors involved. Therefore, achievements are only attributable to the intervention up to a certain level – called the ‘outcome’. Beyond the outcome, effects can no longer be directly linked to this one development intervention. The attribution gap widens at the stage where changes, although observed in the target area, cannot be solely related to project outputs.

Up to where a causal relation between outputs and observed development changes can be demonstrated, projects are entitled to claim the observed development changes as an ‘outcome’ of their activities. Project and programme objectives or targets are set at this level.

Beyond the outcome level, projects and programmes aim at further impacts, which are usually the ultimate reason for the intervention.

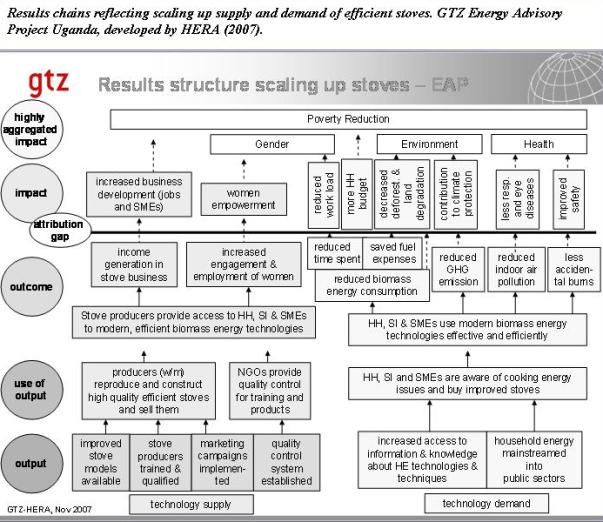

In most cases it is not possible to bring the ‘impact’ into a causal relation, as too many actors are involved to isolate clearly the effect of a single intervention. Nonetheless, the project should seek to address and verify the contribution of the project impacts against highly aggregated development results (as, for instance, the Millennium Development Goals, MDGs). Even though full-scale attribution cannot be done, GTZ expects its managers to provide plausible hypotheses on the projects contributions to high-level development results (Figure8.1).

Examples of results chains for cooking energy projects

The following example of a cooking energy intervention ‘Scaling up of improved biomass stoves’ shows two main chains:

- for stove supply; targeted at producers and traders

- for stove demand; targeting users and the public sector.

Input is not mentioned here, but comprises all the resources provided by all partners: donor organisations, implementers, government partners (money, personnel and material).

Activities that particularly target stove supply include: technology development, training of trainers and producers, marketing, and quality control. Activities focused on stove demand include: mainstreaming cooking energy in the public sector, information and awareness campaigns. They could include establishment of a credit scheme, although this activity is not shown on the table as it was not relevant in this project.

The production outputs of the interventions comprise: improved stove models available, producers trained and qualified, marketing campaigns implemented and quality control system established. This leads to a well-established production and promotion stove initiative, and more stoves on the market.

On the consumption side: the outputs include: increased access to information and knowledge, and household energy mainstreamed into the public sector. This results in more awareness and higher probability of purchase.

Between the output and the use of output lies the system boundary of the project. Up to this point, the project is directly influencing the results; thereafter the success of the intervention is influenced by the targeted groups and their behaviour. But the project is still responsible for achieving results, and therefore the importance of participation and ownership of the target groups becomes very crucial.

The increaseduse of the output, in this case improved biomass stoves, depends on the future users, the project environment and the levels of promotion provided by producers and sales personnel. Support to manufacturers and supplies should be established, or strengthened, by the project.

The outcome of the whole exercise is an increase in access to modern cooking energy technologies. This is the target of the Energy Advisory Project. It enables stove producers to sell their technologies, to generate income and to facilitate the increased involvement of women. Provided that the users cook effectively and efficiently with their new stoves, there will be reduced biomass consumption, a positive impact on time and money, and a reduction in GHG emissions, indoor air pollution, and accidents.

Further results beyond the outcome are not isolated and cannot be attributed to only one project. This is where the attribution gap between outcomes and impacts is located. Impacts are the positive and negative, primary and secondary long-term effects produced by a development intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended. Positive impacts are for example less deforestation, less disease, improved working conditions and more jobs and small / medium enterprises (SMEs) created. A negative impact might be less time for social interaction of women during firewood collection. Where the impacts of scaling up improved biomass stoves finally contribute to the MDGs, they are described as highly aggregated impacts.

Results Based Monitoring is intended to measure the progress and success of the project towards achieving its objectives. To measure this progress, indicators have to be developed. They are quantitative or qualitative values that describe the real situation, and indicate the degree of change. Ideally, these indicators will be measured at the beginning of the project (baseline), during the project, at the end of the project, and perhaps several years later.

The baseline describes the situation prior to the development intervention. It provides a basis against which to monitor whether the intervention has achieved the desired results. Through indicators, project managers are able to trace back the achievement of set targets, to identify unexpected changes, and to identify unintended impacts. It is possible to determine whether outputs achieved have really proved useful, and whether their use has really lead to a worthwhile outcome in development terms. If necessary, the project strategy can be adjusted, additional activities can be included, or further key stakeholders can be involved.

Additional information

- Results chain Ethiopia

- Results chain Kenya

- GTZ - Guidelines for Impact Monitoring in Economic and Employment Promotion Projects with Special Reference to Poverty Reduction Impacts, March 2001; Kuby, Thomas; Vahlhaus, Martina

- GTZ – Measuring Successes and Setbacks. How to Monitor and Evaluate Household Energy Projects. 1996

- GTZ – Results-based Monitoring. Guidelines for Technical Cooperation Projects and Programmes, May 2004

- OECD/DAC – Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results Based Management

UNDP - ‘Energizing the Millennium Development Goals‘, August 2005 - UN Energy - ‘The energy challenge for achieving the Millennium Development Goals, July 2005

Outcome-based monitoring

Each project can be monitored for several factors:

- Levels of output

- Increased capacity of producers,

- Quality control systems,

- Levels of marketing and promotion

- Increased levels of information and knowledge.

To measure the use of the outputs, one would measure the production figures, quality and sales of stoves as well as purchase and awareness of households, social institutions, and SMEs.

To describe the outcomes (depending on the objective of the intervention), all information about access to cooking energy services would be monitored. In this instance, people with access to modern and clean cooking energy would be monitored by sales or construction figures, as well as monitoring correct usage by households, social institutions and SMEs.

The two key outcomes are usually considered to be the reduction of biomass energy consumption, and the reduction in indoor air pollution. Technologies are generally selected by the quality of their performance, efficiency and emission reduction as well as affordability. Tests are conducted in laboratories and at project sites, but of greater importance is the performance under ‘real’ conditions in households, social institutions and SMEs.

The stove’s properties will very much depend on the capacity of the user to achieve maximum efficiency and emission reduction. Users are given kitchen and firewood management training as part of each cooking energy intervention, acquiring knowledge about effective cooking techniques. Projects randomly monitor the in-house performance of stoves: many follow standardised testing procedures. Currently GTZ HERA is coordinating a collection and review of these tests to enable it to provide comparable testing procedures for all projects.

Impacts and Impact assessment

Cooking energy projects that enable access to improved energy, contribute to the MDGs. A plausible hypothesis on the project’s positive impacts to the MDGs should be provided, even though these impacts cannot be monitored, and thus cannot be attributed directly to the intervention.

One to five years after the intervention has been implemented, and when communities have had a chance to use the outputs, it can be worthwhile to do an impact assessment to determine whether the assumptions/ hypotheses on which the project was based have achieved the intended impacts (MDGs).

In these impact assessments, the very specific outcomes are monitored and compared with the baseline. These impacts include; income generated, women engaged in new activities, time and expenses saved, reductions in the levels of indoor air pollution, and reduction in the number of accident, relative to the baseline. They can be directly linked to project interventions. Their contribution to the achievement of impacts, such as increased business development, women’s empowerment, decreased deforestation, decreased respiratory and eye diseases, and finally to the MDGs is assessed and plausibly demonstrated. (It might not always be relevant to carry out an impact assessment and demonstrate relevant impacts within the region where the baseline study was undertaken. This is particularly true with nationwide programmes, or with projects that adopt a market-driven approach.)

Impact assessments have recently been carried out for cooking energy projects in Uganda, Malawi, and Ethiopia. The findings are impressive. Further studies are currently being implemented in Kenya and Bolivia (2008).

Impacts assessment – Methodology and tools<o:p></o:p>

To collect empirical data on the impacts of energy projects, a wide range of methods and approaches is available. These may differ significantly in terms of time, money and expertise needed for implementation. The methods described in the following sections are recommended for measuring energy-related project impacts.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

Generally, methodologies can be divided into quantitative and qualitative methods. Whereas quantitative approaches are concerned to quantify social phenomena by collecting and analysing numerical data, qualitative methods emphasise personal experience and interpretation. (Also qualitative data can be quantified e.g. counting the numbers of people who have expressed the same opinion.) <o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

a) Quantitative Sample Survey<o:p></o:p>

Structured sample surveys are a good way to obtain quantitative information on the life quality of small groups (called ‘sampling units’) such as households, social institutions and SMEs. Scheduled-structured interviews are the most common form in impact assessments. The questions, their wording and their sequence are fixed within a structured questionnaire and identical for every respondent. Beside standardized information, additional qualitative information can be gathered by the use of open questions.

<o:p></o:p>

b) Qualitative Interviews<o:p></o:p>

Qualitative interviews are well suited to reveal background information and detailed opinions regarding particular themes. This type of interview is generally conducted for a small number of sampling units. It is advisable to make use of semi-structured questionnaires containing several open questions.<o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

c) Focus Group Discussions<o:p></o:p>

Focus Group Discussions are one type of qualitative method, allowing interviewers to study people in a more natural setting than in a one-to-one interview. Focus Group Discussions are low in cost, one can get results relatively quickly, and they provide several opinions by talking to several people at once. Care must be taken during these discussions to ensure that those who make the most noise do not dominate the groups with their views. <o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

d) Observations<o:p></o:p>

Observation of the target groups, villages and project interventions through local field staff is a cheap and simple way of gaining a first impression of energy impacts. Even though not as accurate and representative as structured surveys, observations can be especially useful for preparing further scientific research (e.g. questionnaires) by providing site-specific knowledge. <o:p></o:p>

<o:p> </o:p>

e) Document and Statistics Review<o:p></o:p>

Besides information that needs to be gathered from interviews or observations, data on particular indicators might be readily available from local databases, statistics and registers.<o:p></o:p>

UNDP - ‘Energizing the Millennium Development Goals<span /><span /><span />‘, August 2005

UN Energy - ‘The energy challenge for achieving the Millennium Development Goals‘, July 2005

<span style="font: 7pt 'times new roman'" />

- GVEP Guide: For setting up Results Based Monitoring for Energy projects compare GVEP M&EED Guide

http://www.gvepinternational.org/gvep_knowledge_base/monitoring__evaluation This Guide proposes a step by step approach to building project-specific M&E procedures. The guide is intended for energy access projects, which don’t have already donor or stakeholder determined M&E methods. The guide was developed by the International Working Group on Monitoring and Evaluation in Energy for Development (M&EED).

- Boiling Point No 55; http://www.hedon.info/BoilingPoint55-June2008

<span />