Difference between revisions of "SE4Jobs Toolbox - Coordination"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

== <span style="color:#000080">'''SE4Jobs Toolbox''' <span style="color:#000080"><span class="st">– </span>Laying the foundations for a sustainable development</span></span><br/> == | == <span style="color:#000080">'''SE4Jobs Toolbox''' <span style="color:#000080"><span class="st">– </span>Laying the foundations for a sustainable development</span></span><br/> == | ||

| − | + | {{SE4ALL Toolbox}}<br/>{{template:Tabs-5 | |

| − | |||

| − | <br/>{{template:Tabs-5 | ||

|SE4Jobs Toolbox|Overview | |SE4Jobs Toolbox|Overview | ||

|SE4Jobs Toolbox - Assessment|Assessment | |SE4Jobs Toolbox - Assessment|Assessment | ||

| Line 88: | Line 86: | ||

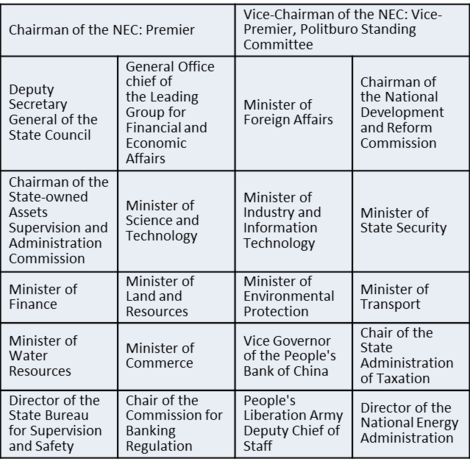

<span style="color:#336699">''In 2010, the Chinese government established the National Energy Commission as a coordination body between the many different ministries involved in energy policy-making. The Commission is tasked with developing the country’s national energy strategy and with better aligning the policies and activities of individual ministries. It plays this role in the absence of a formal ministry for energy. The Commission is led by the Premier and Vice-Premier of the People’s Republic and its membership includes a total of 20 ministries and agencies.''</span> | <span style="color:#336699">''In 2010, the Chinese government established the National Energy Commission as a coordination body between the many different ministries involved in energy policy-making. The Commission is tasked with developing the country’s national energy strategy and with better aligning the policies and activities of individual ministries. It plays this role in the absence of a formal ministry for energy. The Commission is led by the Premier and Vice-Premier of the People’s Republic and its membership includes a total of 20 ministries and agencies.''</span> | ||

| − | '''<span style="color:#336699">'' | + | '''<span style="color:#336699">''Table: Membership in the National Energy Commission''</span>'''<span style="color:#336699"></span> |

| − | <span style="color:#336699">''This overview shows that the National Energy Commission takes a very broad approach and brings to the table all ministries and government agencies involved in energy-related policy matters in order to coordinate government policies effectively. In this sense, it can be considered an example of ‘good practice’ in this issue area. Indeed, a think tank working for the Indian government suggested establishing an analogous commission to coordinate energy policy in India ( | + | [[File:China’s NEC.png|center|470px|alt=China’s NEC.png]] |

| + | |||

| + | <span style="color:#336699">''This overview shows that the National Energy Commission takes a very broad approach and brings to the table all ministries and government agencies involved in energy-related policy matters in order to coordinate government policies effectively. In this sense, it can be considered an example of ‘good practice’ in this issue area. Indeed, a think tank working for the Indian government suggested establishing an analogous commission to coordinate energy policy in India<ref>See the Economic Times of India (2015): http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2015-05-06/news/61865595_1_energy-security-niti-aayog-integrated-energy-policy</ref>.''</span> | ||

'''Vertical coordination across different levels of government''' | '''Vertical coordination across different levels of government''' | ||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

<span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">''China has a long tradition of horizontal climate policy integration on the national level since 1990. Over time, the name of the horizontal coordination mechanism changed and the body was upgraded by being attached to powerful government agencies. First called, in 2003, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and then renamed, in 2007, the ‘National Leading Committee on Climate Change’, it came to be chaired by the Premier and tasked with the coordination of climate change related efforts of national ministries and agencies.''</span></span> | <span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">''China has a long tradition of horizontal climate policy integration on the national level since 1990. Over time, the name of the horizontal coordination mechanism changed and the body was upgraded by being attached to powerful government agencies. First called, in 2003, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and then renamed, in 2007, the ‘National Leading Committee on Climate Change’, it came to be chaired by the Premier and tasked with the coordination of climate change related efforts of national ministries and agencies.''</span></span> | ||

| − | <span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">''Since 2007, there have been analogous leading committees in many provinces, autonomous regions, local municipalities that reinforced the vertical coordination of climate change related policy goals and aligned local efforts more closely with national goals | + | <span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">''Since 2007, there have been analogous leading committees in many provinces, autonomous regions, local municipalities that reinforced the vertical coordination of climate change related policy goals and aligned local efforts more closely with national goals<ref>See Held, et al., "The Governance of Climate Change in China," pg. 24 (2011): http://www.lse.ac.uk/globalGovernance/publications/workingPapers/climateChangeInChina.pdf</ref>. This vertical coordination supported through the institution of the leading committees on climate change plays a particularly important role in such a large country as China. This good practice example is still instructive for other countries in how local counterparts to national agencies can foster the vertical coordination of policies between national, provincial, and local levels.''</span></span> |

'''Coordination with other state actors''' | '''Coordination with other state actors''' | ||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

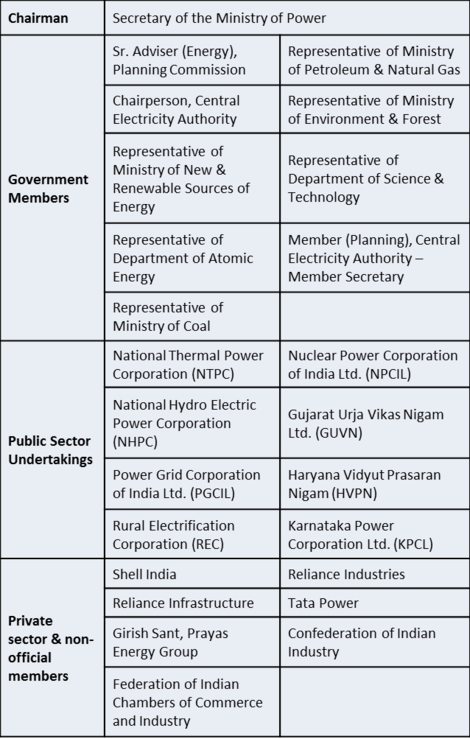

<span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">'''''India: Coordination between ministries, publically owned utilities and non-governmental stakeholders in the development of the Five-Year Plans and climate change policy'''''</span></span> | <span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">'''''India: Coordination between ministries, publically owned utilities and non-governmental stakeholders in the development of the Five-Year Plans and climate change policy'''''</span></span> | ||

| − | <span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">''The steering committee in charge of developing the Indian Five-Year Plan on power and energy policy includes a broad range of governmental and non-governmental actors to foster coordination between nine national government ministries, national and state-level publically owned enterprises (“public sector undertakings”) and non-governmental actors, such as business and civil society representatives. As Indian energy companies play an important role in implementing energy policies, their membership in the development of the five-year plans is an important supportive element for the coordination of government policies. A similarly inclusive approach to membership is taken for the Prime Minister’s Council on Climate Change. The table illustrates the different categories and members in the Steering Committee on Power and Energy. The approach can be considered good practice in that it fosters the alignment of government policies between government ministries, other actors involved in the implementation of these policies – and finally, also the private sector.''</span> </span> | + | <span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">''The steering committee in charge of developing the Indian Five-Year Plan on power and energy policy includes a broad range of governmental and non-governmental actors to foster coordination between nine national government ministries, national and state-level publically owned enterprises (“public sector undertakings”) and non-governmental actors, such as business and civil society representatives. As Indian energy companies play an important role in implementing energy policies, their membership in the development of the five-year plans is an important supportive element for the coordination of government policies. A similarly inclusive approach to membership is taken for the Prime Minister’s Council on Climate Change. The table illustrates the different categories and members in the Steering Committee on Power and Energy. The approach can be considered good practice in that it fosters the alignment of government policies between government ministries, other actors involved in the implementation of these policies – and finally, also the private sector.''</span></span> |

| − | <span style="color:#336699">'''<span style="color:#336699">''<span style="color:#336699"> | + | <span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699"><span style="color:#336699">'''''Table:'''''</span></span></span>'''<span style="color:#336699">''<span style="color:#336699">Membership in India's Steering Committee on Power and Energy</span>''</span>'''</span> |

| − | + | '''[[File:India's SCPE.png|center|470px|alt=India's SCPE.png]]''' | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | === <span style="color:#000000">Challenges in implementing the issue of coordination<span style="color:#000000"><span style="line-height: 21px"><span class="mw-customtoggle-title6" style="font-size:small; font-weight: bold; display:inline-block; float:center; color: blue"><span class="mw-customtoggletext">'''[Expand]'''</span></span></span></span></span><br/> === | |

| − | |||

| − | === <span style="color:# | ||

<div id="mw-customcollapsible-title6" class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | <div id="mw-customcollapsible-title6" class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

| − | * | + | *'''Ensuring effectiveness of coordination'''.<br/>Evidence from the case studies suggests that the main problem with cross-departmental strategies is their actual implementation. Ministries typically focus on ‘their’ key constituencies and ‘their’ own goals and in this way miss out on potential synergies from coordinated action. Regular reviews by independent or top-level actors can highlight such shortcomings and incentivise stronger coordination and cooperation between ministries and their respective associated bodies. |

| − | * | + | *'''Relatively weak political standing of RE and EE'''.<br/>In most countries, RE and EE issues are integrated within the Ministry of Energy (that also represents – often still dominant – fossil fuel interests) or are attached to the Ministry of Environment (which has less political influence). Inter-departmental coordination can therefore lead to RE and EE being treated as niche issues – especially when competing with fossil fuels for political influence. Raising the political profile of RE and EE is therefore an important challenge for proponents of expanding RE and EE. In many cases, actively involving the main political decision-making centres has been a key prerequisite for the ambitious deployment of RE/EE. |

| − | + | </div> | |

| style="width: 5px" | <br/> | | style="width: 5px" | <br/> | ||

| style="width: 150px" | | | style="width: 150px" | | ||

| − | === | + | === Good Practices<br/> === |

| − | + | Brazil | |

| − | + | China<br/> | |

| − | + | India | |

| − | + | Mexico<br/> | |

| − | + | South Africa<br/> | |

| − | + | Turkey<br/> | |

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| + | |||

| + | = Reference = | ||

| + | |||

| + | <references /><br/> | ||

| − | + | {{Re-activate Footer}} __NOTITLE__<br/> | |

Latest revision as of 11:02, 22 November 2017

SE4Jobs Toolbox – Laying the foundations for a sustainable development

| Responsibilities | Coordination | Participation |

ToolsPRODUSE EQuIP CADRE Interactive AILEG HELIO ELMA |

What is the issue coordination about? [Expand]

Coordination of government actors refers to processes, instruments and institutions that ensure the coherence of their policies and activities in developing RE/EE. Coordination aims to create synergies between the goals and measures implemented by the actors involved, including different government departments, and to reduce inconsistencies and countervailing incentives at this level. This is particularly important when it comes to achieving a high share of local value and employment through RE/EE, as the tools, capabilities and responsibilities for promoting these issues generally lie outside the reach of the institutions in charge of energy. The necessary coordination among involved entities can be achieved via different approaches, e.g. by coordination units, inter-ministerial working or steering groups, specific multi-institutional advisory councils or task forces, or joint reporting requirements. Why is coordination between government actors important for the expansion of RE and EE? [Expand]

The aims of developing markets for and employment through RE/EE touch upon a broad range of policy issues and therefore also intersect with the portfolios of many government agencies that, either directly or indirectly, are responsible for developing and implementing policies and activities that are related to RE/EE. The manifold trade-offs and conflicts of goals between these policy issues – and by definition also between the actors in charge of them – have been described in more detail in the issue trade-offs, as have the positive interactions and possible co-benefits in the issue co-benefits. Coordination mechanisms can help to minimize such contradictions and frictions and to foster coherence and synergies among ministries and other governmental actors. This can be achieved by sharing information, pursuing a joint planning approach, defining roles and responsibilities or establishing a joint monitoring system, etc. Particular attention should be paid to coordinating and possibly harmonizing government strategies and policies with the viewpoints and priorities of other concerned actors. These include those who fund, develop, deploy and operate facilities, but also those who will utilize and consume the end product, or who are otherwise affected. Misalignment of government activities with societal objectives and business preferences is a major root cause of policy failure. At the same time, an ‘over-alignment’ can lead to equally negative consequences. For example, it can result in policy capture by vested ‘rent-seeking’ interests and lead to significant welfare losses among the populations involved. Walking the thin line between these two scenarios is the essence of good policy and a major precondition for a truly sound and sustainable RE/EE deployment. What are key questions for addressing the issue of coordination? [Expand]

The challenge of coordinating government entities that are implementing policies relevant to RE/EE can be addressed along three different lines:

How can the issue of coordination be addressed? [Expand]

A first step can be to review coordination mechanisms that already are used to coordinate government actors in other policy fields: How have these mechanisms been set up? Who manages them? How regularly do they take place? Who is involved in them? Is there a coordinating role for the president’s or prime minister’s office? And most importantly: do they have proper decision-making functions, or are they mere communication channels? A second step is to evaluate whether these coordination mechanisms include those actors that matter for policies that aim to maximize the socio-economic co-benefits of RE/EE. This is crucial as most of the policy resources needed in this regard are found outside the energy sector and involve a wide range of actors from a variety of policy domains that are usually not aware of or even interested in energy issues. This is often especially the case with actors concerned with industrial development, employment, research, innovation, education and training, housing and spatial planning, climate and environment, etc. A third step is to adjust the coordination mechanisms accordingly, either by creating formal inter-sectorial working groups and task forces and decision or advisory bodies, or by creating more informal forums for cross-sectorial exchange and cooperation. In any case, correctly identifying the most relevant interlocutors in the various institutions involved, as well as clear support from, if not the direct involvement of, the political top decision maker(s) is key for the success of this approach. A final step is to evaluate how crucial it is to also coordinate strategy and policy development with state and local governments. In what specific fields are government actors at the subnational level crucial in implementing policy or in overcoming barriers to the roll-out of RE/EE? This is especially important in the case of EE, as sub-national authorities (e.g. municipalities) often have major rule-setting and implementing functions for the building sector, public transport and other important public services. Similarly, in some countries, publically owned companies implement government policies – e.g. in financing investments, producing energy, managing the grid, etc. As such, they have a major stake in maintaining the status quo. How can these companies be integrated in the (further) development of RE/EE strategies and policies? Practical aspects of coordination and good practice options [Expand]

Horizontal coordination between government ministries Horizontal coordination within government between different ministries with a stake in energy policy is a key feature that can be found in virtually all of the countries investigated. The degree to which this horizontal coordination is ‘institutionalized’ varies between them, but in principle it can be found everywhere. This horizontal coordination is a particularly crucial element for any successful harnessing of the socio-economic benefits of RE/EE for the local population, for the reasons pointed out before, and should allow for a mobilization and alignment of policy instruments and resources in a wide range of relevant areas such as industrial policy, employment, research, innovation, education and training, housing and spatial planning, climate and environment, etc. China’s National Energy Commission as a coordination body for government ministries In 2010, the Chinese government established the National Energy Commission as a coordination body between the many different ministries involved in energy policy-making. The Commission is tasked with developing the country’s national energy strategy and with better aligning the policies and activities of individual ministries. It plays this role in the absence of a formal ministry for energy. The Commission is led by the Premier and Vice-Premier of the People’s Republic and its membership includes a total of 20 ministries and agencies. Table: Membership in the National Energy Commission This overview shows that the National Energy Commission takes a very broad approach and brings to the table all ministries and government agencies involved in energy-related policy matters in order to coordinate government policies effectively. In this sense, it can be considered an example of ‘good practice’ in this issue area. Indeed, a think tank working for the Indian government suggested establishing an analogous commission to coordinate energy policy in India[1]. Vertical coordination across different levels of government Energy policy-making is typically led by the national government level. However, in many countries, some areas that are relevant for the development of RE and even more for that of EE are managed by subnational (state or local) governments. To ensure consistency and coherence in how strategies and policies are being developed and implemented, coordination is also important between these different levels of government. Such vertical coordination can be realized through the participation of subnational government representatives in the policy processes on the national level or through their membership in joint institutions tasked with the coordination of government efforts across different levels. China: Horizontal and vertical policy coordination through coordination bodies on climate change China has a long tradition of horizontal climate policy integration on the national level since 1990. Over time, the name of the horizontal coordination mechanism changed and the body was upgraded by being attached to powerful government agencies. First called, in 2003, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and then renamed, in 2007, the ‘National Leading Committee on Climate Change’, it came to be chaired by the Premier and tasked with the coordination of climate change related efforts of national ministries and agencies. Since 2007, there have been analogous leading committees in many provinces, autonomous regions, local municipalities that reinforced the vertical coordination of climate change related policy goals and aligned local efforts more closely with national goals[2]. This vertical coordination supported through the institution of the leading committees on climate change plays a particularly important role in such a large country as China. This good practice example is still instructive for other countries in how local counterparts to national agencies can foster the vertical coordination of policies between national, provincial, and local levels. Coordination with other state actors Beyond ministries and other government agencies on the national or sub-national levels, there are key players that hold important functions for the successful implementation of RE/EE policies. Such actors include publically owned companies, development banks and regulatory agencies. Their actions can be coordinated in various ways, e.g. with the help of legal acts, through membership in formal government coordination mechanisms, or through ad hoc inter-institutional coordination arrangements. India: Coordination between ministries, publically owned utilities and non-governmental stakeholders in the development of the Five-Year Plans and climate change policy The steering committee in charge of developing the Indian Five-Year Plan on power and energy policy includes a broad range of governmental and non-governmental actors to foster coordination between nine national government ministries, national and state-level publically owned enterprises (“public sector undertakings”) and non-governmental actors, such as business and civil society representatives. As Indian energy companies play an important role in implementing energy policies, their membership in the development of the five-year plans is an important supportive element for the coordination of government policies. A similarly inclusive approach to membership is taken for the Prime Minister’s Council on Climate Change. The table illustrates the different categories and members in the Steering Committee on Power and Energy. The approach can be considered good practice in that it fosters the alignment of government policies between government ministries, other actors involved in the implementation of these policies – and finally, also the private sector. Table:Membership in India's Steering Committee on Power and Energy Challenges in implementing the issue of coordination[Expand]

|

Good Practices

Brazil China India Mexico South Africa Turkey |

Reference

- ↑ See the Economic Times of India (2015): http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2015-05-06/news/61865595_1_energy-security-niti-aayog-integrated-energy-policy

- ↑ See Held, et al., "The Governance of Climate Change in China," pg. 24 (2011): http://www.lse.ac.uk/globalGovernance/publications/workingPapers/climateChangeInChina.pdf

|

This article is part of the RE-ACTIVATE project. RE-ACTIVATE “Promoting Employment through Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in the MENA Region” is implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). |