Difference between revisions of "Impact of Energy Access on Enterprises"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

This article discusses the link between energy access and productivity and seeks to determine the specific sectors or entrepreneurs that suffer a lot from lack of energy access and would therefore benefit the most from access to energy. | This article discusses the link between energy access and productivity and seeks to determine the specific sectors or entrepreneurs that suffer a lot from lack of energy access and would therefore benefit the most from access to energy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 24: | ||

A direct positive impact of electricity on productivity was found to a lesser extent. In all of the assessed direct and indirect potential impacts, the majority of papers found impacts to be taking place only in some circumstances. These findings suggest that enterprises were not suffering excessively from lack of access to energy before electrification. If they had, more significant developments in business environment and productivity would be expected. | A direct positive impact of electricity on productivity was found to a lesser extent. In all of the assessed direct and indirect potential impacts, the majority of papers found impacts to be taking place only in some circumstances. These findings suggest that enterprises were not suffering excessively from lack of access to energy before electrification. If they had, more significant developments in business environment and productivity would be expected. | ||

| − | To which extent energy access enables expansion of businesses also depends largely on the demand of products and services. Furthermore, a study carried out in the Indian Himalayas on the role of energy in poverty reduction through small scale enterprises found out that in almost all of the monitored businesses the demand throughout most of the year was below their capacity. Thus, expansion of working hours or acquisition of electrical appliances did not seem needed (Dijk, 2008). Similar observations were made in Tanzania, Bolivia and Vietnam where in several cases saturation of the market occurred after electrification which lead to reduced profits (Kooijman-van Dijk and Clancy, 2010).<ref name="Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004">Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004</ref> | + | To which extent energy access enables expansion of businesses also depends largely on the demand of products and services. Therefore, if the market is saturated, increased use of electricity by some enterprises might lead to customer numbers decreasing for financially weaker enterprises since the electrified businesses can open longer and deliver a higher quality of products (Harsdorff and Bamanyaki, 2009).<ref name="Harsdorff, M., Bamanyaki, P., 2009. IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE SOLAR ELECTRIFICATION OF MICRO ENTERPRISES, HOUSEHOLDS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE RURAL SOLAR MARKET. Promot. Renew. Energy Energy Effic. Programme PREEEP gtz.">Harsdorff, M., Bamanyaki, P., 2009. IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE SOLAR ELECTRIFICATION OF MICRO ENTERPRISES, HOUSEHOLDS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE RURAL SOLAR MARKET. Promot. Renew. Energy Energy Effic. Programme PREEEP gtz.</ref> Furthermore, a study carried out in the Indian Himalayas on the role of energy in poverty reduction through small scale enterprises found out that in almost all of the monitored businesses the demand throughout most of the year was below their capacity. Thus, expansion of working hours or acquisition of electrical appliances did not seem needed (Dijk, 2008). Similar observations were made in Tanzania, Bolivia and Vietnam where in several cases saturation of the market occurred after electrification which lead to reduced profits (Kooijman-van Dijk and Clancy, 2010).<ref name="Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004">Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004</ref> |

Also, sectors were identified where investments in machines and appliances are generally low and the operation scale is restricted by the local market size (e.g. general stores or tailoring), hence energy access did not automatically imply enhanced productivity. Therefore, this finding cannot be generalised and further research is still necessary to fully understand the link between financial starting position of the entrepreneurs, incomes generated from the enterprise and uptake of modern energy appliances. | Also, sectors were identified where investments in machines and appliances are generally low and the operation scale is restricted by the local market size (e.g. general stores or tailoring), hence energy access did not automatically imply enhanced productivity. Therefore, this finding cannot be generalised and further research is still necessary to fully understand the link between financial starting position of the entrepreneurs, incomes generated from the enterprise and uptake of modern energy appliances. | ||

| Line 31: | Line 33: | ||

The above shows the complexity that comes with trying to measure the impact of energy access on productivity. These income-related outcomes of energy access not only depend on electricity but also on a wide range of other factors collectively enabling its productive use (Allderdice and Rogers, 2000; Pueyo et al., 2013).<ref name="Allderdice, A., Rogers, J.H., 2000. Renewable Energy for Microenterprise. Colo. Natl. Renew. Energy Lab.">Allderdice, A., Rogers, J.H., 2000. Renewable Energy for Microenterprise. Colo. Natl. Renew. Energy Lab.</ref><ref name="Pueyo, A., Gonzalez, F., Dent, C., DeMartino, S., 2013. The Evidence of Benefits for Poor People of Increased Access Renewable Electricity Capacity: Literature Review. Brighton Inst. Dev. Stud.">Pueyo, A., Gonzalez, F., Dent, C., DeMartino, S., 2013. The Evidence of Benefits for Poor People of Increased Access Renewable Electricity Capacity: Literature Review. Brighton Inst. Dev. Stud.</ref> | The above shows the complexity that comes with trying to measure the impact of energy access on productivity. These income-related outcomes of energy access not only depend on electricity but also on a wide range of other factors collectively enabling its productive use (Allderdice and Rogers, 2000; Pueyo et al., 2013).<ref name="Allderdice, A., Rogers, J.H., 2000. Renewable Energy for Microenterprise. Colo. Natl. Renew. Energy Lab.">Allderdice, A., Rogers, J.H., 2000. Renewable Energy for Microenterprise. Colo. Natl. Renew. Energy Lab.</ref><ref name="Pueyo, A., Gonzalez, F., Dent, C., DeMartino, S., 2013. The Evidence of Benefits for Poor People of Increased Access Renewable Electricity Capacity: Literature Review. Brighton Inst. Dev. Stud.">Pueyo, A., Gonzalez, F., Dent, C., DeMartino, S., 2013. The Evidence of Benefits for Poor People of Increased Access Renewable Electricity Capacity: Literature Review. Brighton Inst. Dev. Stud.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 43: | Line 47: | ||

The availability, quality and cost of producer services are integral for the manufacturing sector. Thus, improvements in service industries such as communication, financial and electricity services boost productivity of manufacturing enterprises, and therefore are a fundamental element of a strategy for reducing poverty and promoting growth (Arnold et al., 2008).<ref name="Arnold, J.M., Mattoo, A., Narciso, G., 2008. Services Inputs and Firm Productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Firm-Level Data. J. Afr. Econ. 17, 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejm042">Arnold, J.M., Mattoo, A., Narciso, G., 2008. Services Inputs and Firm Productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Firm-Level Data. J. Afr. Econ. 17, 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejm042</ref> | The availability, quality and cost of producer services are integral for the manufacturing sector. Thus, improvements in service industries such as communication, financial and electricity services boost productivity of manufacturing enterprises, and therefore are a fundamental element of a strategy for reducing poverty and promoting growth (Arnold et al., 2008).<ref name="Arnold, J.M., Mattoo, A., Narciso, G., 2008. Services Inputs and Firm Productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Firm-Level Data. J. Afr. Econ. 17, 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejm042">Arnold, J.M., Mattoo, A., Narciso, G., 2008. Services Inputs and Firm Productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Firm-Level Data. J. Afr. Econ. 17, 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejm042</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 50: | Line 56: | ||

In less industrialised countries agriculture is one of the primary economic activities. Access to energy provides possibilities to increase productivity of several agricultural tasks (Etcheverry, 2003).<ref name="Etcheverry, J., 2003. Renewable Energy for Productive Uses: Strategies to Enhance Environmental Protection and the Quality of Rural Life. Univ. Tor. Glob. Environ. Facil. Wash. DC.">Etcheverry, J., 2003. Renewable Energy for Productive Uses: Strategies to Enhance Environmental Protection and the Quality of Rural Life. Univ. Tor. Glob. Environ. Facil. Wash. DC.</ref> The drudgery with physical labour and animal power can be diminished through energy access. For example in Uganda where human power makes up 90% of all energy used in agriculture, animal power amounts to about 8% and fossil fuels contribute about 2% (Turyareeba, 2001).<ref name="Turyareeba, P.., 2001. Renewable energy: its contribution to improved standards of living and modernisation of agriculture in Uganda. Renew. Energy 24, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(01)00028-3">Turyareeba, P.., 2001. Renewable energy: its contribution to improved standards of living and modernisation of agriculture in Uganda. Renew. Energy 24, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(01)00028-3</ref> Kirubi et al. further explain how access to electricity plays an important role to better exploitation of the local agricultural potential. Before farmers cultivated their land solely manually. With electricity access, electrical welding services for repairing tractors became locally available thus allowing more and more people to bring and rent tractors to farmers. Also, local farmers and traders struggle with the storage of perishable farm products such as meat and milk. Electricity enables them to store farm produce as well as other consumer goods such as soft and alcoholic drinks (Kirubi et al., 2009).<ref name="Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005">Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005</ref> Other agricultural uses of electricity are e.g. tea processing, grain milling or water pumping. Interestingly, in wealthier villages access to electricity is used for a variety of income generating activities, whereas in poorer villages it is mainly used for agro-processing (Kooijman-van Dijk and Clancy, 2010).<ref name="Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004">Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004</ref> | In less industrialised countries agriculture is one of the primary economic activities. Access to energy provides possibilities to increase productivity of several agricultural tasks (Etcheverry, 2003).<ref name="Etcheverry, J., 2003. Renewable Energy for Productive Uses: Strategies to Enhance Environmental Protection and the Quality of Rural Life. Univ. Tor. Glob. Environ. Facil. Wash. DC.">Etcheverry, J., 2003. Renewable Energy for Productive Uses: Strategies to Enhance Environmental Protection and the Quality of Rural Life. Univ. Tor. Glob. Environ. Facil. Wash. DC.</ref> The drudgery with physical labour and animal power can be diminished through energy access. For example in Uganda where human power makes up 90% of all energy used in agriculture, animal power amounts to about 8% and fossil fuels contribute about 2% (Turyareeba, 2001).<ref name="Turyareeba, P.., 2001. Renewable energy: its contribution to improved standards of living and modernisation of agriculture in Uganda. Renew. Energy 24, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(01)00028-3">Turyareeba, P.., 2001. Renewable energy: its contribution to improved standards of living and modernisation of agriculture in Uganda. Renew. Energy 24, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(01)00028-3</ref> Kirubi et al. further explain how access to electricity plays an important role to better exploitation of the local agricultural potential. Before farmers cultivated their land solely manually. With electricity access, electrical welding services for repairing tractors became locally available thus allowing more and more people to bring and rent tractors to farmers. Also, local farmers and traders struggle with the storage of perishable farm products such as meat and milk. Electricity enables them to store farm produce as well as other consumer goods such as soft and alcoholic drinks (Kirubi et al., 2009).<ref name="Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005">Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005</ref> Other agricultural uses of electricity are e.g. tea processing, grain milling or water pumping. Interestingly, in wealthier villages access to electricity is used for a variety of income generating activities, whereas in poorer villages it is mainly used for agro-processing (Kooijman-van Dijk and Clancy, 2010).<ref name="Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004">Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004</ref> | ||

| − | On the other hand, a literature review on this matter found other studies that claimed there was no substantial impact of access to electricity on agricultural productivity since e.g. irrigation could also be realized with mechanically powered or diesel pumps. (“Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action,” 2015).<ref name="Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action [WWW Document], 2015. URL http://practicalaction.org/utilising (accessed 4.5.16).">Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action [WWW Document], 2015. URL http://practicalaction.org/utilising (accessed 4.5.16).</ref> | + | On the other hand, a literature review on this matter found other studies that claimed there was no substantial impact of access to electricity on agricultural productivity since e.g. irrigation could also be realized with mechanically powered or diesel pumps. (“Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action,” 2015).<ref name="Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action [WWW Document], 2015. URL http://practicalaction.org/utilising (accessed 4.5.16).">Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action [WWW Document], 2015. URL http://practicalaction.org/utilising (accessed 4.5.16).</ref> However, the consensus trends towards the recognition of a positive impact of energy access on agricultural productivity. Another argument being that the availability of more efficient agro-processing services which are modern and less labour-intensive attracts customers and investments from other villages (Legros et al., 2011).<ref name="Legros, G., Rijal, K., Bahareh, S., 2011. Decentralized energy access and the millennium development goals: an analysis of the development benefits of micro-hydropower in rural Nepal. Alternative Energy Promotion Centre, Bourton on Dunsmore, Rugby, Warwickshire, UK.">Legros, G., Rijal, K., Bahareh, S., 2011. Decentralized energy access and the millennium development goals: an analysis of the development benefits of micro-hydropower in rural Nepal. Alternative Energy Promotion Centre, Bourton on Dunsmore, Rugby, Warwickshire, UK.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 61: | Line 71: | ||

Similar findings were made on the Philippines where home businesses that used electricity directly in their businesses accumulated up to four more working hours per day in comparison to households that did not have access to electricity. Further it was found that a quarter (25%) of electrified households run a home business as opposed to only 14.8% of non-electrified households. This may imply that households with electricity access were more likely to run a business at home (ESMAP, 2002).<ref name="ESMAP, 2002. Rural Electrification and Development in the Philippines: Measuring the Social and Economic Benefits. ESMAP Rep., Report 255/02.">ESMAP, 2002. Rural Electrification and Development in the Philippines: Measuring the Social and Economic Benefits. ESMAP Rep., Report 255/02.</ref> | Similar findings were made on the Philippines where home businesses that used electricity directly in their businesses accumulated up to four more working hours per day in comparison to households that did not have access to electricity. Further it was found that a quarter (25%) of electrified households run a home business as opposed to only 14.8% of non-electrified households. This may imply that households with electricity access were more likely to run a business at home (ESMAP, 2002).<ref name="ESMAP, 2002. Rural Electrification and Development in the Philippines: Measuring the Social and Economic Benefits. ESMAP Rep., Report 255/02.">ESMAP, 2002. Rural Electrification and Development in the Philippines: Measuring the Social and Economic Benefits. ESMAP Rep., Report 255/02.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A common home business emerging with availability of electricity is mobile phone charging (Karugu and Kimani, n.d.).<ref name="Karugu, W.N., Kimani, D.W., n.d. ToughStuff East Africa: Affordable Quality Solar Alternatives for Low Income Consumers in Kenya. UNDP.">Karugu, W.N., Kimani, D.W., n.d. ToughStuff East Africa: Affordable Quality Solar Alternatives for Low Income Consumers in Kenya. UNDP.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 77: | Line 91: | ||

Consequently, a boost in income levels of 20-70% depending on the product manufactured was observed (Kirubi et al., 2009). <ref name="Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005">Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005</ref>Yet, the small sample size of 5 and 12 artisans makes the findings questionable. | Consequently, a boost in income levels of 20-70% depending on the product manufactured was observed (Kirubi et al., 2009). <ref name="Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005">Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005</ref>Yet, the small sample size of 5 and 12 artisans makes the findings questionable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mobile phone charging is also a common productive use of electricity. This service can be offered in small shops or even specific phone charging kiosks (Collings, 2011).<ref name="Collings, S., 2011. Phone Charging Micro-businesses in Tanzania and Uganda. GVEP Int. de Gouvello, C., Durix, L., 2008. Maximizing the Productive Uses of Electricity to Increase the Impact of Rural Electrifi cation Programs. ESMAP.">Collings, S., 2011. Phone Charging Micro-businesses in Tanzania and Uganda. GVEP Int.fckLRde Gouvello, C., Durix, L., 2008. Maximizing the Productive Uses of Electricity to Increase the Impact of Rural Electrifi cation Programs. ESMAP.fckLR</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A study carried out in Tanzania observed that the surveyed beer brewing microenterprises used electricity merely for lighting and playing the radio. The actual brewing process was still completed with biomass since the entrepreneurs were dreaded the high bills at the end of the month (Maleko, 2005).<ref name="Maleko, G.C., 2005. IMPACT OF ELECTRICITY SERVICES ON MICROENTERPRISE IN RURAL AREAS IN TANZANIA. Dep. ENERGY Sustain. Dev. Univ. TWENTE ENSCHEDE.">Maleko, G.C., 2005. IMPACT OF ELECTRICITY SERVICES ON MICROENTERPRISE IN RURAL AREAS IN TANZANIA. Dep. ENERGY Sustain. Dev. Univ. TWENTE ENSCHEDE.</ref> Thus, not all entrepreneurs are actually able to benefit fully from energy access due to lack of affordability. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | == Enabling environment == | + | == Enabling environment: banks, telecommunications == |

Access to energy also impacts the local banking and communication services as a study in Kenya showed. The local bank and several private shops were found using electronic equipment (e.g. computers, printers, and photocopiers), hence improving the enabling environment for business service delivery (Kirubi et al., 2009).<ref name="Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005">Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005</ref> | Access to energy also impacts the local banking and communication services as a study in Kenya showed. The local bank and several private shops were found using electronic equipment (e.g. computers, printers, and photocopiers), hence improving the enabling environment for business service delivery (Kirubi et al., 2009).<ref name="Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005">Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005</ref> | ||

| Line 88: | Line 108: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | < | + | = Summary: Scientific findings on the impact of electricity<ref>Source: Based on Carsten Hellpap, 2018: How to promote productive use of solar power in rural Africa?, http://www.energy-access-conferences.com/17286/section/13892/international-conference-on-solar-technologies-and-hybrid-mini-grids-to-improve-energy-access.html. and https://english.iob-evaluatie.nl/publications/reports/2013/03/01/376---iob-study-renewable-energy-access-and-impact.-a-systematic-literature-review-kopie</ref> = |

| + | |||

| + | Expenditures: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Shift from kerosene, paraffin, candles, dry cell batteries to PV electricity → reduction in expenditure for lighting (often in the range of 10%). | ||

| + | *Electricity enables households to use new appliances → increased energy consumption and increased household expenditures (between 20 and 50%) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Use for productive purposes in small enterprises and businesses | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Conflicting results: in some cases economic growth/additional income as a result of access to electricity. Other studies did not find such effects, even when villages were connected to the grid. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Observations | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Existing enterprises invest in electricity and appliances, but often do not achieve higher profits. | ||

| + | *Income and employment generation by newly established firms, highly dependent on electricity for their operations | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

= Conclusion = | = Conclusion = | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Positive correlation between energy and economic development not in the short term | ||

| + | *<div>An effect generally occurs over a longer period of time linked to new companies, effective use of energy, general market and income development.</div> | ||

| + | *<div>Additional measures are needed such as<br/>- access to finance<br/>- access to machinery and equipment<br/>- business development support<br/>- marketing support regarding the existing market value chains and new markets.<ref>Source: Based on Carsten Hellpap, 2018: How to promote productive use of solar power in rural Africa?, http://www.energy-access-conferences.com/17286/section/13892/international-conference-on-solar-technologies-and-hybrid-mini-grids-to-improve-energy-access.html. and https://english.iob-evaluatie.nl/publications/reports/2013/03/01/376---iob-study-renewable-energy-access-and-impact.-a-systematic-literature-review-kopie</ref></div> | ||

Regarding microenterprises the significant criteria implying a positive impact of energy access is if electrical appliances are a requirement in this sector and how strong the local demand is. If there is no need for electrical appliances electrification does not have a meaningful impact on the productivity of this specific sector. Also, as long as the demand remains the same, additional working hours and increased output are pointless. | Regarding microenterprises the significant criteria implying a positive impact of energy access is if electrical appliances are a requirement in this sector and how strong the local demand is. If there is no need for electrical appliances electrification does not have a meaningful impact on the productivity of this specific sector. Also, as long as the demand remains the same, additional working hours and increased output are pointless. | ||

| Line 104: | Line 142: | ||

Nonetheless, the following table gives an overview with examples of businesses that suffer a lot and those who do not suffer as much from lack of energy. The examples are categorised into being impacted by energy access in a positive, non-significant or a negative way (but are displayed in no particular order). | Nonetheless, the following table gives an overview with examples of businesses that suffer a lot and those who do not suffer as much from lack of energy. The examples are categorised into being impacted by energy access in a positive, non-significant or a negative way (but are displayed in no particular order). | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

{| style="width:100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | {| style="width:100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | ||

| Line 123: | Line 161: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | | <br/> | + | | |

| + | *[[PicoPV for Mobile Charging|PicoPV for Mobile Charging]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Productive End Use of PicoPV#Direct Productive Use of PicoPV: Mobile Charging|Direct Productive Use of PicoPV: Mobile Charging]]<br/> | ||

| + | |||

|- | |- | ||

| <br/> | | <br/> | ||

| − | | Businesses that use electricity | + | | Businesses that use electricity<br/> |

| | | | ||

*Manufacturing | *Manufacturing | ||

| Line 132: | Line 173: | ||

*Service industry (small shops, laundry, barber shop etc.) | *Service industry (small shops, laundry, barber shop etc.) | ||

*Microenterprises like carpenters and tailors | *Microenterprises like carpenters and tailors | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*Hotels/Tourism sector | *Hotels/Tourism sector | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | *[[Solar Water Heaters – Project Examples#Productive Use: The Colca River Hotel|Solar Water Heaters Productive Use: The Colca River Hotel]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Micro Hydro Power and Productive Use Promotion (GIZ ESRA Afghanistan)|Afghanistan Micro Hydro Power and Productive Use Promotion]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Tomato Processing by Solar Energy|Tomato Processing by Solar Energy]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Smart Grid on Main Street: Electricity and Value-added Processing for Agricultural Goods|Smart Grid on Main Street: Electricity and Value-added Processing for Agricultural Goods]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[IDEAS Innovation Contest|IDEAS Innovation Contest]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Photovoltaic (PV) Pumping in India|Photovoltaic (PV) Pumping in India]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Powering Agriculture: An Energy Grand Challenge for Development initiative - Winners|Powering Agriculture: An Energy Grand Challenge for Development initiative - Winners]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Sheabutter Processing|Sheabutter Processing]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Implementing a Productive Use Grant Scheme in Uganda|Implementing a Productive Use Grant Scheme in Uganda]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Solar Milk Cooling|Solar Milk Cooling]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2014/oct/08/can-coffee-stimulate-renewable-energy-in-central-america Energy from Coffee Waste Water]<br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| <br/> | | <br/> | ||

| + | | Businesses that use other energy sources (e.g. Biomass) | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | *Breweries<br/> | ||

| + | *Bakeries | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | *[[Baking with Improved Ovens|Baking with Improved Ovens]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Indicator Rural Electrification and Stoves#Beneficiaries: Productive Stove Users .28PU.29 - Restaurants.2C Beer Breweries.2C Bakeries|Productive Stove Users: Restaurants, Beer Breweries, Bakeries]]<br/> | ||

| + | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Type of businesses that are not impacted by energy access<br/> | | Type of businesses that are not impacted by energy access<br/> | ||

| Line 148: | Line 210: | ||

| <br/> | | <br/> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 154: | Line 220: | ||

= Further information = | = Further information = | ||

| − | <br/>[[Productive Use of Energy for Rural Development|Productive Use of Energy for Rural Development]] | + | |

| + | *[[:Portal:Productive Use|Productive Use Portal]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Productive Use of Energy for Rural Development|Productive Use of Energy for Rural Development]] | ||

| + | *[[Productive Use of Energy - Approaches of GIZ Projects|Productive Use of Energy - Approaches of GIZ Projects]] | ||

| + | *[[Productive Use of Electricity|Productive Use of Electricity]] | ||

| + | *[https://cleanenergysolutions.org/sites/default/files/documents/productive-uses-of-energy-monika-giz-presentation.pdf Productive Uses of Energy: Experiences, publications, guidance and tools]<br/> | ||

| + | *[https://practicalaction.org/utilising Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Mini-grid Webinar Series|Webinar Case Study from Indonesia, Myanmar and Nepal]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Energy for Agriculture|Energy for Agriculture]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Energy Needs in Smallholder Agriculture|Energy Needs in Smallholder Agriculture]]<br/> | ||

| + | *[[File:EUEI PDF ProductiveUseElectricityManual.pdf|180px|EUEI PDF: Productive Use Manual for Electrification Practitioners|alt=EUEI PDF: Productive Use Manual for Electrification Practitioners]]<br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 160: | Line 239: | ||

<references /><br/> | <references /><br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Rural_Electrification]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Impacts_Economic]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Productive_Use]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Energy_Use]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Energy_Access]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:59, 13 November 2018

Overview

Initially most energy access projects implemented in rural areas of less industrialised countries aimed at domestic use of energy. After realising the potential of access to energy to improve rural sustainability and economic growth, more and more initiatives and projects have emerged that focus on providing energy access for productive use. Furthermore, in poor areas where customers are not able to pay for energy services, it is difficult for energy suppliers to establish feasible operation. Therefore, where subsidies are limited productive use of energy can enhance the viability of energy delivery (Dijk, 2008).[1]

Nevertheless, to which extent access to modern energies truly impacts poverty reduction and entrepreneurial success remains unclear. Especially in rural areas the evaluation of the effective benefits of energy access is intricate (de Gouvello and Durix, 2008; Dijk, 2008; “Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action,” 2015).[2][1][3] Thus, how and if it affects which sector and which entrepreneurs has yet been difficult to conclude.

This article discusses the link between energy access and productivity and seeks to determine the specific sectors or entrepreneurs that suffer a lot from lack of energy access and would therefore benefit the most from access to energy.

Energy Access and Productivity

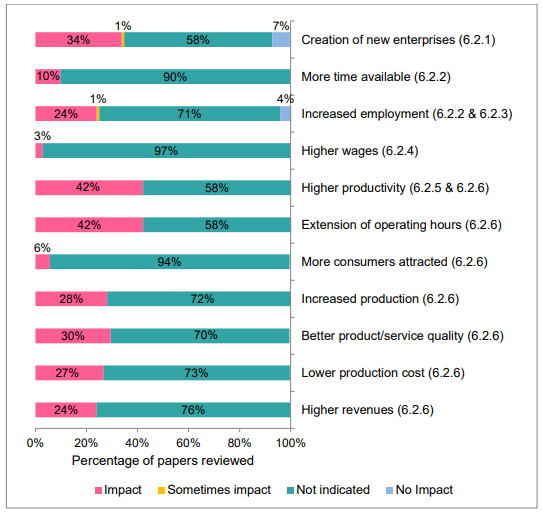

The general consensus is that access to energy leads to enterprise creation and increased employment. Yet, regarding employee remuneration studies found that male’s wages increased with electricity whereas women’s wages decreased. In addition, research revealed an increase in revenues and profits through longer working hours and better productivity, enabled by improved electricity access. Nonetheless, the impacts observed and measured are mainly small. Interestingly, after electrification pre-existing or newly created firms that do not depend on electricity perform worse than enterprises created after electrification that rely on electricity. Even though many agree on the positive impact of electrification a literature review by Practical Action displayed in Figure 1 produced interesting findings. The papers were examined and categorised by the following criteria: if a positive impact was found, if no significant impact was found, if the impacts found only took place in some circumstances or if the issue of impact of energy access was not analysed at all. (“Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action,” 2015).[3]

A direct positive impact of electricity on productivity was found to a lesser extent. In all of the assessed direct and indirect potential impacts, the majority of papers found impacts to be taking place only in some circumstances. These findings suggest that enterprises were not suffering excessively from lack of access to energy before electrification. If they had, more significant developments in business environment and productivity would be expected.

To which extent energy access enables expansion of businesses also depends largely on the demand of products and services. Therefore, if the market is saturated, increased use of electricity by some enterprises might lead to customer numbers decreasing for financially weaker enterprises since the electrified businesses can open longer and deliver a higher quality of products (Harsdorff and Bamanyaki, 2009).[4] Furthermore, a study carried out in the Indian Himalayas on the role of energy in poverty reduction through small scale enterprises found out that in almost all of the monitored businesses the demand throughout most of the year was below their capacity. Thus, expansion of working hours or acquisition of electrical appliances did not seem needed (Dijk, 2008). Similar observations were made in Tanzania, Bolivia and Vietnam where in several cases saturation of the market occurred after electrification which lead to reduced profits (Kooijman-van Dijk and Clancy, 2010).[5]

Also, sectors were identified where investments in machines and appliances are generally low and the operation scale is restricted by the local market size (e.g. general stores or tailoring), hence energy access did not automatically imply enhanced productivity. Therefore, this finding cannot be generalised and further research is still necessary to fully understand the link between financial starting position of the entrepreneurs, incomes generated from the enterprise and uptake of modern energy appliances.

The study also showed the uptake and different impacts in relation to the assets of the entrepreneurs. It revealed that investments in modern energy and electrical appliances is higher for higher income groups (Dijk, 2008).[1]

The above shows the complexity that comes with trying to measure the impact of energy access on productivity. These income-related outcomes of energy access not only depend on electricity but also on a wide range of other factors collectively enabling its productive use (Allderdice and Rogers, 2000; Pueyo et al., 2013).[6][7]

Entrepreneurs that Profit from Energy Access

Manufacturing sector

The availability, quality and cost of producer services are integral for the manufacturing sector. Thus, improvements in service industries such as communication, financial and electricity services boost productivity of manufacturing enterprises, and therefore are a fundamental element of a strategy for reducing poverty and promoting growth (Arnold et al., 2008).[8]

Agricultural sector

In less industrialised countries agriculture is one of the primary economic activities. Access to energy provides possibilities to increase productivity of several agricultural tasks (Etcheverry, 2003).[9] The drudgery with physical labour and animal power can be diminished through energy access. For example in Uganda where human power makes up 90% of all energy used in agriculture, animal power amounts to about 8% and fossil fuels contribute about 2% (Turyareeba, 2001).[10] Kirubi et al. further explain how access to electricity plays an important role to better exploitation of the local agricultural potential. Before farmers cultivated their land solely manually. With electricity access, electrical welding services for repairing tractors became locally available thus allowing more and more people to bring and rent tractors to farmers. Also, local farmers and traders struggle with the storage of perishable farm products such as meat and milk. Electricity enables them to store farm produce as well as other consumer goods such as soft and alcoholic drinks (Kirubi et al., 2009).[11] Other agricultural uses of electricity are e.g. tea processing, grain milling or water pumping. Interestingly, in wealthier villages access to electricity is used for a variety of income generating activities, whereas in poorer villages it is mainly used for agro-processing (Kooijman-van Dijk and Clancy, 2010).[5]

On the other hand, a literature review on this matter found other studies that claimed there was no substantial impact of access to electricity on agricultural productivity since e.g. irrigation could also be realized with mechanically powered or diesel pumps. (“Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action,” 2015).[3] However, the consensus trends towards the recognition of a positive impact of energy access on agricultural productivity. Another argument being that the availability of more efficient agro-processing services which are modern and less labour-intensive attracts customers and investments from other villages (Legros et al., 2011).[12]

Home businesses

The impact of energy access is greater for home businesses than for medium and large enterprises. An analysis of data from 1988 to 2003 by the World Bank’s IEG showed that the number of small home enterprises - such as renting out refrigerator space - increased significantly more in communities that became electrified in comparison to other communities that were already or were never electrified. Further, electrification enables home businesses to extend their working hours thus, increasing their net income (World Bank, 2008).[13]

Similar findings were made on the Philippines where home businesses that used electricity directly in their businesses accumulated up to four more working hours per day in comparison to households that did not have access to electricity. Further it was found that a quarter (25%) of electrified households run a home business as opposed to only 14.8% of non-electrified households. This may imply that households with electricity access were more likely to run a business at home (ESMAP, 2002).[14]

A common home business emerging with availability of electricity is mobile phone charging (Karugu and Kimani, n.d.).[15]

Micro enterprises

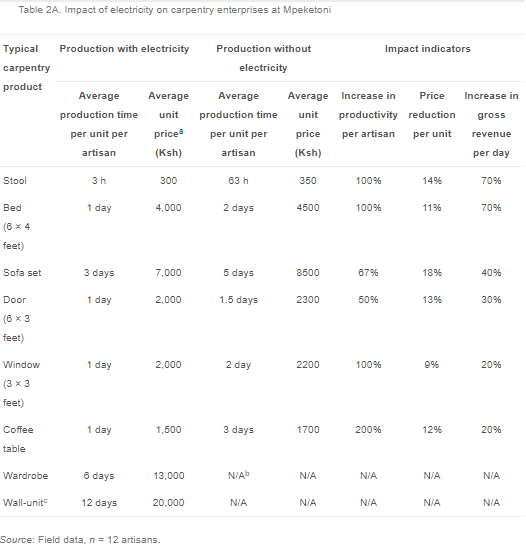

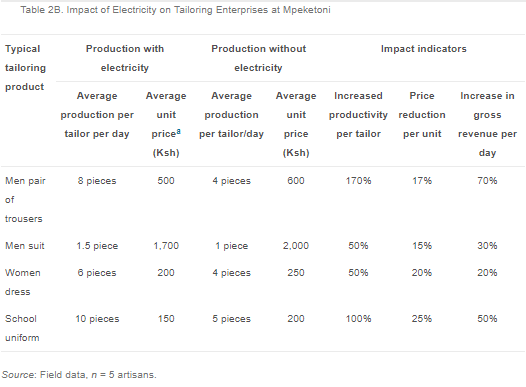

Concerning the business of carpenters and tailors, a study in Kenya found that energy access resulted in a 100-200% increase of production depending on the task at hand (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The access to electricity allowed the entrepreneurs to acquire and use electric tools as opposed to manual labour, thus enabling them to step up productivity.

Consequently, a boost in income levels of 20-70% depending on the product manufactured was observed (Kirubi et al., 2009). [11]Yet, the small sample size of 5 and 12 artisans makes the findings questionable.

Mobile phone charging is also a common productive use of electricity. This service can be offered in small shops or even specific phone charging kiosks (Collings, 2011).[16]

A study carried out in Tanzania observed that the surveyed beer brewing microenterprises used electricity merely for lighting and playing the radio. The actual brewing process was still completed with biomass since the entrepreneurs were dreaded the high bills at the end of the month (Maleko, 2005).[17] Thus, not all entrepreneurs are actually able to benefit fully from energy access due to lack of affordability.

Enabling environment: banks, telecommunications

Access to energy also impacts the local banking and communication services as a study in Kenya showed. The local bank and several private shops were found using electronic equipment (e.g. computers, printers, and photocopiers), hence improving the enabling environment for business service delivery (Kirubi et al., 2009).[11]

Arnold et al. specifically examined the relationship of access to reliable services inputs and the productivity of African manufacturing firms. The analysed service sectors were banking, telecommunications and electricity distribution. The study revealed a significant and positive correlation between service performance and firm productivity. Regarding electricity, inadequate provision of power can disturb the production processes and cause productive assets to be unusable and inoperative, thus decreasing productivity (Arnold et al., 2008).[8]

Summary: Scientific findings on the impact of electricity[18]

Expenditures:

- Shift from kerosene, paraffin, candles, dry cell batteries to PV electricity → reduction in expenditure for lighting (often in the range of 10%).

- Electricity enables households to use new appliances → increased energy consumption and increased household expenditures (between 20 and 50%)

Use for productive purposes in small enterprises and businesses

- Conflicting results: in some cases economic growth/additional income as a result of access to electricity. Other studies did not find such effects, even when villages were connected to the grid.

Observations

- Existing enterprises invest in electricity and appliances, but often do not achieve higher profits.

- Income and employment generation by newly established firms, highly dependent on electricity for their operations

Conclusion

- Positive correlation between energy and economic development not in the short term

- An effect generally occurs over a longer period of time linked to new companies, effective use of energy, general market and income development.

- Additional measures are needed such as

- access to finance

- access to machinery and equipment

- business development support

- marketing support regarding the existing market value chains and new markets.[19]

Regarding microenterprises the significant criteria implying a positive impact of energy access is if electrical appliances are a requirement in this sector and how strong the local demand is. If there is no need for electrical appliances electrification does not have a meaningful impact on the productivity of this specific sector. Also, as long as the demand remains the same, additional working hours and increased output are pointless.

Medium and larger enterprises may have the possibility to import physical inputs from other countries; however, these enterprises heavily rely on the state of locally produced services such as electricity, financial services and communications. Whereby, the establishment of financial services and communications requires improved and reliable electrification.

Generally home businesses seem to benefit the most from access to modern energies.

The majority of studies touching this topic of the relationship of energy access and productive use and poverty reduction mainly focusses on the outcomes and the post-electrification scenario. Precise observations and comparisons of before and after situations is lacking. Further research on the improvements and changes after electrification for specific sectors and entrepreneurs is needed in order to judge how much different sectors suffer from lack of energy access. Questions such as: “Which entrepreneurs suffer the most or the least from lack of energy access?” remain unanswered.

Nonetheless, the following table gives an overview with examples of businesses that suffer a lot and those who do not suffer as much from lack of energy. The examples are categorised into being impacted by energy access in a positive, non-significant or a negative way (but are displayed in no particular order).

| Impact of energy access (positive, not significant, negative) |

Categories of types of enterprises |

Examples |

Energypedia articles or webpages with examples |

| Type of business that suffers from lack of energy access |

Type of businesses that only exist with access to energy |

|

|

| Businesses that use electricity |

|

| |

| Businesses that use other energy sources (e.g. Biomass) |

|

||

| Type of businesses that are not impacted by energy access |

Those that do not need electrical appliances or thermal energy supply |

||

| Type of businesses that performs worse in case of energy access |

Non-energy related businesses in electrified villages |

Further information

- Productive Use Portal

- Productive Use of Energy for Rural Development

- Productive Use of Energy - Approaches of GIZ Projects

- Productive Use of Electricity

- Productive Uses of Energy: Experiences, publications, guidance and tools

- Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction

- Webinar Case Study from Indonesia, Myanmar and Nepal

- Energy for Agriculture

- Energy Needs in Smallholder Agriculture

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dijk, A.L. van, 2008. The power to produce: the role of energy in poverty reduction through small scale enterprises in the Indian Himalayas.

- ↑ de Gouvello, C., Durix, L., 2008. Maximizing the Productive Uses of Electricity to Increase the Impact of Rural Electrifi cation Programs. ESMAP.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Utilising Electricity Access for Poverty Reduction | Practical Action Consulting | Practical Action [WWW Document], 2015. URL http://practicalaction.org/utilising (accessed 4.5.16).

- ↑ Harsdorff, M., Bamanyaki, P., 2009. IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE SOLAR ELECTRIFICATION OF MICRO ENTERPRISES, HOUSEHOLDS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE RURAL SOLAR MARKET. Promot. Renew. Energy Energy Effic. Programme PREEEP gtz.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kooijman-van Dijk, A.L., Clancy, J., 2010. Impacts of Electricity Access to Rural Enterprises in Bolivia, Tanzania and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2009.12.004

- ↑ Allderdice, A., Rogers, J.H., 2000. Renewable Energy for Microenterprise. Colo. Natl. Renew. Energy Lab.

- ↑ Pueyo, A., Gonzalez, F., Dent, C., DeMartino, S., 2013. The Evidence of Benefits for Poor People of Increased Access Renewable Electricity Capacity: Literature Review. Brighton Inst. Dev. Stud.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Arnold, J.M., Mattoo, A., Narciso, G., 2008. Services Inputs and Firm Productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Firm-Level Data. J. Afr. Econ. 17, 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejm042

- ↑ Etcheverry, J., 2003. Renewable Energy for Productive Uses: Strategies to Enhance Environmental Protection and the Quality of Rural Life. Univ. Tor. Glob. Environ. Facil. Wash. DC.

- ↑ Turyareeba, P.., 2001. Renewable energy: its contribution to improved standards of living and modernisation of agriculture in Uganda. Renew. Energy 24, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(01)00028-3

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005

- ↑ Legros, G., Rijal, K., Bahareh, S., 2011. Decentralized energy access and the millennium development goals: an analysis of the development benefits of micro-hydropower in rural Nepal. Alternative Energy Promotion Centre, Bourton on Dunsmore, Rugby, Warwickshire, UK.

- ↑ World Bank, 2008. The Welfare Impact of Rural Electrification: A Reassessment of the Costs and Benefits. The World Bank.

- ↑ ESMAP, 2002. Rural Electrification and Development in the Philippines: Measuring the Social and Economic Benefits. ESMAP Rep., Report 255/02.

- ↑ Karugu, W.N., Kimani, D.W., n.d. ToughStuff East Africa: Affordable Quality Solar Alternatives for Low Income Consumers in Kenya. UNDP.

- ↑ Collings, S., 2011. Phone Charging Micro-businesses in Tanzania and Uganda. GVEP Int.fckLRde Gouvello, C., Durix, L., 2008. Maximizing the Productive Uses of Electricity to Increase the Impact of Rural Electrifi cation Programs. ESMAP.fckLR

- ↑ Maleko, G.C., 2005. IMPACT OF ELECTRICITY SERVICES ON MICROENTERPRISE IN RURAL AREAS IN TANZANIA. Dep. ENERGY Sustain. Dev. Univ. TWENTE ENSCHEDE.

- ↑ Source: Based on Carsten Hellpap, 2018: How to promote productive use of solar power in rural Africa?, http://www.energy-access-conferences.com/17286/section/13892/international-conference-on-solar-technologies-and-hybrid-mini-grids-to-improve-energy-access.html. and https://english.iob-evaluatie.nl/publications/reports/2013/03/01/376---iob-study-renewable-energy-access-and-impact.-a-systematic-literature-review-kopie

- ↑ Source: Based on Carsten Hellpap, 2018: How to promote productive use of solar power in rural Africa?, http://www.energy-access-conferences.com/17286/section/13892/international-conference-on-solar-technologies-and-hybrid-mini-grids-to-improve-energy-access.html. and https://english.iob-evaluatie.nl/publications/reports/2013/03/01/376---iob-study-renewable-energy-access-and-impact.-a-systematic-literature-review-kopie