Difference between revisions of "Financing Sustainable Urban Transport"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) m |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

*'''Private Sector '''– who operate public transport, manufacture vehicles, and provide infrastructure. Some of these services are provided informally, e.g. rickshaws and motorcycle taxis). | *'''Private Sector '''– who operate public transport, manufacture vehicles, and provide infrastructure. Some of these services are provided informally, e.g. rickshaws and motorcycle taxis). | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]]<br/> |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

== What needs to be financed? == | == What needs to be financed? == | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

These elements must all be supported, in order to enable a sustainable urban transport system and maximize its efficiency. Addressing the current challenges require much more than investing in additional transport infrastructure projects, but rather the re-examination of urban transport as a whole system, and building a financing framework to maximise its potential. | These elements must all be supported, in order to enable a sustainable urban transport system and maximize its efficiency. Addressing the current challenges require much more than investing in additional transport infrastructure projects, but rather the re-examination of urban transport as a whole system, and building a financing framework to maximise its potential. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

== What are the barriers that need to be acknowledged? == | == What are the barriers that need to be acknowledged? == | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

*Public acceptance – whereby care must be taken to minimise public resistance to the implementation of new financing instruments. | *Public acceptance – whereby care must be taken to minimise public resistance to the implementation of new financing instruments. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

= Approaches Towards a Sustainable System<ref name="Sakamoto K., Belka S., Dr. Metschies G. 2010, Financing Sustainable Urban Transport, Eschborn Germany">Sakamoto K., Belka S., Dr. Metschies G. 2010, Financing Sustainable Urban Transport, Eschborn Germany</ref> = | = Approaches Towards a Sustainable System<ref name="Sakamoto K., Belka S., Dr. Metschies G. 2010, Financing Sustainable Urban Transport, Eschborn Germany">Sakamoto K., Belka S., Dr. Metschies G. 2010, Financing Sustainable Urban Transport, Eschborn Germany</ref> = | ||

| − | == | + | == Understanding and Managing the Financial Requirements for Sustainable Transport == |

The first step towards reaching the aforementioned goals is to understand the financing needs. The estimation of such requirements must be embedded within: | The first step towards reaching the aforementioned goals is to understand the financing needs. The estimation of such requirements must be embedded within: | ||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

*Identifying trends in expenditure increases which may jeopardize financial sustainability. | *Identifying trends in expenditure increases which may jeopardize financial sustainability. | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Financing Sustainable Urban Transport#Why is financing so important.3F|►Go to Top]] |

== Understanding the Various Financing Options/Mechanisms == | == Understanding the Various Financing Options/Mechanisms == | ||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

The majority of financial instruments that are available at local and national levels are those which have a history of use within the transport sector, whereas those at the international level include innovative instruments that have lately been conceived with the specific intention of promoting environmental objectives, particularly climate change mitigation. | The majority of financial instruments that are available at local and national levels are those which have a history of use within the transport sector, whereas those at the international level include innovative instruments that have lately been conceived with the specific intention of promoting environmental objectives, particularly climate change mitigation. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

== Financing Instruments at Local Level == | == Financing Instruments at Local Level == | ||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

Parking charges are often used in place of direct road user charges, and their ability to be differentiated by time and place makes them an appropriate demand management measure that can be alter to internalise some of the negative externalities generated by the mode. Not all cities charge for the use of parking facilities however, and parking is often subsidised. Even where charges are applied there is a tendency for them to be undercharged, which leads to an efficient allocation of space in urban areas. Parking charges can vary based on geographical area, day, time, duration of stay and emissions generated from each vehicle. In association with other measures increasing parking charges in city centres can, for example, reduce congestion and promote public transport use. Furthermore, on-street charges should if possible be higher than off-street charges as this will act as an incentive for people to park off-street, rather than look for a cheaper (as well more convenient) on-street space. As a rule of thumb parking fees per hour should be higher than single bus fare in order to encourage the use of public transport. | Parking charges are often used in place of direct road user charges, and their ability to be differentiated by time and place makes them an appropriate demand management measure that can be alter to internalise some of the negative externalities generated by the mode. Not all cities charge for the use of parking facilities however, and parking is often subsidised. Even where charges are applied there is a tendency for them to be undercharged, which leads to an efficient allocation of space in urban areas. Parking charges can vary based on geographical area, day, time, duration of stay and emissions generated from each vehicle. In association with other measures increasing parking charges in city centres can, for example, reduce congestion and promote public transport use. Furthermore, on-street charges should if possible be higher than off-street charges as this will act as an incentive for people to park off-street, rather than look for a cheaper (as well more convenient) on-street space. As a rule of thumb parking fees per hour should be higher than single bus fare in order to encourage the use of public transport. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

=== Road Pricing and Congestion Charging === | === Road Pricing and Congestion Charging === | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

Charges can subsequently vary based upon geographical area, vehicle type, day, time, and (when using more advanced systems) upon levels of congestion. This flexibility is the major strength of road pricing, and provides scope to best implement the user-pays principle. This is largely owing to the fact that car owner-ship in developing countries is predominantly by those who earn relatively high-incomes, and who are likely to attach the highest value to reduced travel time and increased reliability. Revenues of charges can be reinvested in wider urban transport modes, such as public transport, to improve options for modal shift. It can also be used to help service capital payments and to maintain the infrastructure, so that benefits of the charge are immediately perceived by the users. | Charges can subsequently vary based upon geographical area, vehicle type, day, time, and (when using more advanced systems) upon levels of congestion. This flexibility is the major strength of road pricing, and provides scope to best implement the user-pays principle. This is largely owing to the fact that car owner-ship in developing countries is predominantly by those who earn relatively high-incomes, and who are likely to attach the highest value to reduced travel time and increased reliability. Revenues of charges can be reinvested in wider urban transport modes, such as public transport, to improve options for modal shift. It can also be used to help service capital payments and to maintain the infrastructure, so that benefits of the charge are immediately perceived by the users. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

=== Employer Contributions === | === Employer Contributions === | ||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

Employer contributions are given by business to support local transport. They are paid directly to the local transport. They are paid directly to the local authority as a tax, or provided as a subsidy to employees to pay for their transport fares. Employer contributions can only be imposed if there is an enabling legislative framework. With an appropriate legislative framework in place, the revenues provide reliable and long-term income. | Employer contributions are given by business to support local transport. They are paid directly to the local transport. They are paid directly to the local authority as a tax, or provided as a subsidy to employees to pay for their transport fares. Employer contributions can only be imposed if there is an enabling legislative framework. With an appropriate legislative framework in place, the revenues provide reliable and long-term income. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

=== Public Transport Subsidies === | === Public Transport Subsidies === | ||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

Public transport subsidies must be coupled with measures and regulation to ensure that they are used effectively and not wasted. This is owing to the potential for subsidies to be misused or poorly managed. A preferable alternative to subsidising services is to capitalise upon different user preferences by supplying different products to different segments of the market. Subsidies can also be reduced through increasing the role of the private sector, which often increases the efficiency of operation. These processes can be used to introduce competition and lead to the lowering of fares without the need for subsidy. However, measures such as performance based contracts must be in place to mitigate the disadvantages of private sector involvement. | Public transport subsidies must be coupled with measures and regulation to ensure that they are used effectively and not wasted. This is owing to the potential for subsidies to be misused or poorly managed. A preferable alternative to subsidising services is to capitalise upon different user preferences by supplying different products to different segments of the market. Subsidies can also be reduced through increasing the role of the private sector, which often increases the efficiency of operation. These processes can be used to introduce competition and lead to the lowering of fares without the need for subsidy. However, measures such as performance based contracts must be in place to mitigate the disadvantages of private sector involvement. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

== Financing Instruments at National Level == | == Financing Instruments at National Level == | ||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

Fuel taxes are popular mechanism to raise revenue, either for the general account or for transport-specific usage. It is a relatively simple and reliable way of charging, and their implementation and enforcement are both less problematic than alternative revenue raising approaches. Fuel taxes can be used as a stable source of revenue for the maintenance of, and in some cases such as Japan the construction of road infrastructure. Fuel tax can also be considered a way to implement the user-pays principle, as fuel consumption can generally be regarded as a good indication of the level use of road infrastructure. The main weakness of the fuel tax is that is cannot differentiate charges adequately to reflect the nature in which the vehicle is used. However, unlike more sophisticated instruments such as road pricing scheme, they are relatively easy to administer and hard to avoid. It is also prone to (indirect) subsidies, reflecting political pressure to keep fuel prices low. Revenues from fuel tax tend to accrue at a national rather than local level, thereby making it difficult for the instrument to be co-ordinated with urban strategies. | Fuel taxes are popular mechanism to raise revenue, either for the general account or for transport-specific usage. It is a relatively simple and reliable way of charging, and their implementation and enforcement are both less problematic than alternative revenue raising approaches. Fuel taxes can be used as a stable source of revenue for the maintenance of, and in some cases such as Japan the construction of road infrastructure. Fuel tax can also be considered a way to implement the user-pays principle, as fuel consumption can generally be regarded as a good indication of the level use of road infrastructure. The main weakness of the fuel tax is that is cannot differentiate charges adequately to reflect the nature in which the vehicle is used. However, unlike more sophisticated instruments such as road pricing scheme, they are relatively easy to administer and hard to avoid. It is also prone to (indirect) subsidies, reflecting political pressure to keep fuel prices low. Revenues from fuel tax tend to accrue at a national rather than local level, thereby making it difficult for the instrument to be co-ordinated with urban strategies. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

=== Vehicle Taxation === | === Vehicle Taxation === | ||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

Vehicle taxation, which is also known as road taxation, is a tax on car ownership that is typically payable on an annual basis, although it is also levied on the acquisition of vehicles. It follows the principle of redistribution, meaning that more affluent groups, who are able to purchase their own vehicles, are taxed and therefore have to contribute more to infrastructure maintenance and extension than the poor. Vehicle taxation is similar to fuel tax in that it directly falls upon those who use the infrastructure and that the revenues can be used to support. Vehicle taxation is known to be generally the second largest source of revenue from transport, following fuel taxes. It can therefore be used to fund the maintenance of urban roads, or other more sustainable forms of urban transport provision, such as public transport. Vehicle tax can be varied depending upon engine size or carbon emissions. Thus, vehicle tax can be used to encourage car owners to purchase vehicles with a better environmental performance. | Vehicle taxation, which is also known as road taxation, is a tax on car ownership that is typically payable on an annual basis, although it is also levied on the acquisition of vehicles. It follows the principle of redistribution, meaning that more affluent groups, who are able to purchase their own vehicles, are taxed and therefore have to contribute more to infrastructure maintenance and extension than the poor. Vehicle taxation is similar to fuel tax in that it directly falls upon those who use the infrastructure and that the revenues can be used to support. Vehicle taxation is known to be generally the second largest source of revenue from transport, following fuel taxes. It can therefore be used to fund the maintenance of urban roads, or other more sustainable forms of urban transport provision, such as public transport. Vehicle tax can be varied depending upon engine size or carbon emissions. Thus, vehicle tax can be used to encourage car owners to purchase vehicles with a better environmental performance. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

In many developing cities, the borrowing ability for urban transport is often restricted by the availability of future revenue to support the borrowing, as well as the legal framework, which can set a limit on the amount that can be borrowed without the consent of central government. The key purpose of such limits is to ensure that borrowing is affordable, although in smaller cities his may be owing to the fact that national government needs to borrow on their behalf. Grants and loans are also provided by foreign sources, e.g. in the form of official development aid (ODA). These are provided by governments of industrialised countries, either bilaterally, or through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, providing in total billions of dollars worth of transport investments every year. However, most of the funding is channeled into road building, which does not always support the goal of sustainable urban transport. | In many developing cities, the borrowing ability for urban transport is often restricted by the availability of future revenue to support the borrowing, as well as the legal framework, which can set a limit on the amount that can be borrowed without the consent of central government. The key purpose of such limits is to ensure that borrowing is affordable, although in smaller cities his may be owing to the fact that national government needs to borrow on their behalf. Grants and loans are also provided by foreign sources, e.g. in the form of official development aid (ODA). These are provided by governments of industrialised countries, either bilaterally, or through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, providing in total billions of dollars worth of transport investments every year. However, most of the funding is channeled into road building, which does not always support the goal of sustainable urban transport. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

*Consider the development of an urban transport fund – as a potential vehicle to ensure sustainable urban transport financing. Certain income sources can also be earmarked (or ring-fenced) to improve the stability and predictability of resources. | *Consider the development of an urban transport fund – as a potential vehicle to ensure sustainable urban transport financing. Certain income sources can also be earmarked (or ring-fenced) to improve the stability and predictability of resources. | ||

| − | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport# | + | [[Financing_Sustainable_Urban_Transport#toc|►Go to Top]] |

= Further Information = | = Further Information = | ||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| + | [[Category:Transport]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Financing_and_Funding]] | ||

[[Category:Mobility]] | [[Category:Mobility]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 13:14, 20 August 2014

► Back to Financing and Funding Portal

The Importance of Finance in Sustainable Urban Transport[1]

Why is financing so important?

The rapid increase in motorized traffic increases congestion, air pollution and accidents, whose costs fall back to the city and its citizens in terms of lower productivity, fuel costs and health/hospitalization costs. In cities across the world, the inadequate and inappropriate urban transport financial arrangements are largely responsible for the worsening urban transport situation.

Who is involved in financing urban transport?

The major actors include:

- City administration– who are responsible for raising local financial resources, coordinating funding, implementing policies and in many countries operating public transport systems directly.

- National and Regional Governments – who raise resources at national/regional level, and set rules for the allocation and redistribution of resources between national and local levels.

- Citizens – who use urban transport systems, pay taxes, charges and fees, as well as take ultimate responsibility of public policy as voters.

- Donors/International organisations – who provide financing (through Official Development Assistance – ODA), technology and knowledge, as well as promote good governance.

- Private Sector – who operate public transport, manufacture vehicles, and provide infrastructure. Some of these services are provided informally, e.g. rickshaws and motorcycle taxis).

The Double Challenge: Financing Sustainable Urban Transport, Sustainably[1]

How can urban transport be financed in a sustainable way?

At a very crude level, financing sustainability is met when revenues are balanced with expenditures, in other words when total intake/income is equal to or exceeds spending. Maintaining this balance needs to be considered at all levels of decision making, namely:

- Policy level, when deciding on the urban transport budget for the whole city.

- Programme level, in developing a group of projects to support e.g. the rollout of a new network of Bus Rapid Transit;

- Project level, i.e. in executing individual projects under various programmes (e.g. construction of separated bus lanes, purchase of buses)

The funding of infrastructure often becomes financially unsustainable when shortfalls in revenue (e.g. through the under-pricing of infrastructure use and lack of stable income source) is combined with excess in expenditure (e.g. through poorly controlled costs, political changes and/or corruption). Investments require up-front funding but it is essential that over the longer term the revenue covers the financing, operating and maintenance costs.

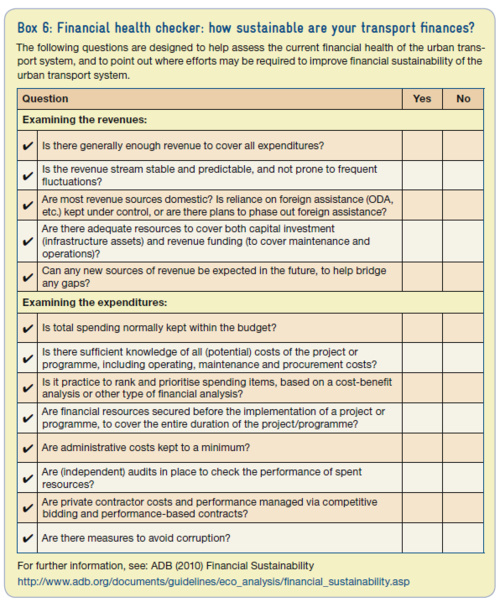

Public transport services often become financially unsustainable due to a combination of poorly structured subsidies, improper fare controls, inefficient operations and poor financial management. Problems with funding are often interlinked and represent/share a larger, underlying problem. This provides the case for a wider and deeper analysis of the current problems, which may involve consultations and joint working with various stakeholders, including citizens, other government bodies and the private sector. The box below provides a number of questions to help assess the financial sustainability of urban transport.

What needs to be financed?

The financing of urban transport requires at a very crude level the coverage of two main aspects, namely:

- Capital investments for infrastructure – which are normally expensive, fixed assets such as railways, bus ways, cycle paths, tramlines, stations, roads and bridges. This also includes investments in new technologies, such as the purchase of vehicles, as well as system-wide technologies, such as Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS). Such investments normally require large levels of financial resources, and are often not met solely from local sources. Therefore, the role of national governments and international donors (through the provision of loans and grants, as well as leveraging private capital) become important.

- Recurrent expenditures– which require a continuous stream of financial resources long after the capital investment take place. This includes the operation of public transport, paratransit and other transport services, the maintenance of infrastructure, administrative costs for city administrations, police, and other public functions, support for policies and programmes – such as legislation, regulation and traffic rules, air quality management programmes, safety campaigns, and traffic management – including signalling, bus lanes, priority at crossings, etc.

These elements must all be supported, in order to enable a sustainable urban transport system and maximize its efficiency. Addressing the current challenges require much more than investing in additional transport infrastructure projects, but rather the re-examination of urban transport as a whole system, and building a financing framework to maximise its potential.

What are the barriers that need to be acknowledged?

The issue of transport finance does not exist in isolation from a wider set of issues that determine the ability for cities to meet the aforementioned goals of developing a sustainable transport system. In reality, the effective financing of a sustainable urban transport system is undermined by various other factors, which need to be fully understood and appropriately managed. These include:

- Trends in economic development – which results in rapid urbanisation, income growth and developments in other sectors of the economy, leading to increased demand for motorised transport.

- Systematic bias towards funding unsustainable transport (e.g. urban highways and flyovers) – by national and local governments, as well as donors, particularly on infrastructure for motorised private transport.

- Transport prices that do not reflect true costs – whereby motorists are not charged the full costs of his/her travel activity, such as those imposed on others in society through increased congestion, accidents, infrastructure wear and tear, air pollution, noise and climate change.

- Governance and institutional factors – including the lack of institutional capacity to raise and manage funding at the local level, poor coordination and fragmentation of responsibilities between the relevant (transport) authorities (i.e. between modes, between infrastructure and operations, and between pricing and service provision).

- Public acceptance – whereby care must be taken to minimise public resistance to the implementation of new financing instruments.

Approaches Towards a Sustainable System[1]

Understanding and Managing the Financial Requirements for Sustainable Transport

The first step towards reaching the aforementioned goals is to understand the financing needs. The estimation of such requirements must be embedded within:

- A holistic decision-making process for estimating the costs and benefits of transport schemes, fully taking into account their social and environmental impacts.

- A robust framework for estimating/forecasting the potential expenditures and revenues throughout the entire lifetime of the programme or project, taking into account any risks.

- A transparent and fully accountable system of monitoring costs.

Accurate and consistent accounting for transport expenditures is very important. This provides the basis for:

- Assessing any potential shortfalls or gaps in funding that may be need to be addressed; and

- Identifying trends in expenditure increases which may jeopardize financial sustainability.

Understanding the Various Financing Options/Mechanisms

Once the areas which are inadequately or improperly funded are identified, and incentives created to minimise unnecessary expenditures, an appropriate set of financing instruments must be selected to plug the gap and improve support for sustainable transport.

The majority of financial instruments that are available at local and national levels are those which have a history of use within the transport sector, whereas those at the international level include innovative instruments that have lately been conceived with the specific intention of promoting environmental objectives, particularly climate change mitigation.

Financing Instruments at Local Level

Parking Charges

Parking charges are often used in place of direct road user charges, and their ability to be differentiated by time and place makes them an appropriate demand management measure that can be alter to internalise some of the negative externalities generated by the mode. Not all cities charge for the use of parking facilities however, and parking is often subsidised. Even where charges are applied there is a tendency for them to be undercharged, which leads to an efficient allocation of space in urban areas. Parking charges can vary based on geographical area, day, time, duration of stay and emissions generated from each vehicle. In association with other measures increasing parking charges in city centres can, for example, reduce congestion and promote public transport use. Furthermore, on-street charges should if possible be higher than off-street charges as this will act as an incentive for people to park off-street, rather than look for a cheaper (as well more convenient) on-street space. As a rule of thumb parking fees per hour should be higher than single bus fare in order to encourage the use of public transport.

Road Pricing and Congestion Charging

Road pricing involves directly charging road users within a defined area for their use of road space. There are many forms of road pricing, including:

- Cordon pricing – where charges are levied for access to limited geographical areas, and charges are often differentiated based on time of day.

- Time-dependent tolling – applied to individual roads or lanes in targeted areas; and

- Electronic road pricing – which enables more stringent differentiation of charges by road, time of use and type of vehicle over a specified area.

Charges can subsequently vary based upon geographical area, vehicle type, day, time, and (when using more advanced systems) upon levels of congestion. This flexibility is the major strength of road pricing, and provides scope to best implement the user-pays principle. This is largely owing to the fact that car owner-ship in developing countries is predominantly by those who earn relatively high-incomes, and who are likely to attach the highest value to reduced travel time and increased reliability. Revenues of charges can be reinvested in wider urban transport modes, such as public transport, to improve options for modal shift. It can also be used to help service capital payments and to maintain the infrastructure, so that benefits of the charge are immediately perceived by the users.

Employer Contributions

Employer contributions are given by business to support local transport. They are paid directly to the local transport. They are paid directly to the local authority as a tax, or provided as a subsidy to employees to pay for their transport fares. Employer contributions can only be imposed if there is an enabling legislative framework. With an appropriate legislative framework in place, the revenues provide reliable and long-term income.

Public Transport Subsidies

Public transport subsidies must be coupled with measures and regulation to ensure that they are used effectively and not wasted. This is owing to the potential for subsidies to be misused or poorly managed. A preferable alternative to subsidising services is to capitalise upon different user preferences by supplying different products to different segments of the market. Subsidies can also be reduced through increasing the role of the private sector, which often increases the efficiency of operation. These processes can be used to introduce competition and lead to the lowering of fares without the need for subsidy. However, measures such as performance based contracts must be in place to mitigate the disadvantages of private sector involvement.

Financing Instruments at National Level

Fuel Taxes/Surcharges

Fuel taxes are popular mechanism to raise revenue, either for the general account or for transport-specific usage. It is a relatively simple and reliable way of charging, and their implementation and enforcement are both less problematic than alternative revenue raising approaches. Fuel taxes can be used as a stable source of revenue for the maintenance of, and in some cases such as Japan the construction of road infrastructure. Fuel tax can also be considered a way to implement the user-pays principle, as fuel consumption can generally be regarded as a good indication of the level use of road infrastructure. The main weakness of the fuel tax is that is cannot differentiate charges adequately to reflect the nature in which the vehicle is used. However, unlike more sophisticated instruments such as road pricing scheme, they are relatively easy to administer and hard to avoid. It is also prone to (indirect) subsidies, reflecting political pressure to keep fuel prices low. Revenues from fuel tax tend to accrue at a national rather than local level, thereby making it difficult for the instrument to be co-ordinated with urban strategies.

Vehicle Taxation

Vehicle taxation, which is also known as road taxation, is a tax on car ownership that is typically payable on an annual basis, although it is also levied on the acquisition of vehicles. It follows the principle of redistribution, meaning that more affluent groups, who are able to purchase their own vehicles, are taxed and therefore have to contribute more to infrastructure maintenance and extension than the poor. Vehicle taxation is similar to fuel tax in that it directly falls upon those who use the infrastructure and that the revenues can be used to support. Vehicle taxation is known to be generally the second largest source of revenue from transport, following fuel taxes. It can therefore be used to fund the maintenance of urban roads, or other more sustainable forms of urban transport provision, such as public transport. Vehicle tax can be varied depending upon engine size or carbon emissions. Thus, vehicle tax can be used to encourage car owners to purchase vehicles with a better environmental performance.

National and International Loans and Grants

Loans, in particular those provided by national or international public bodies, may allow the local authority to borrow at significantly lower interest compared to raising funding on the private market. Borrowing through such concessional loans, with a few percentage differences in the interest rate, may amount to millions of dollars of savings for the local authority over a course of the project.

In many developing cities, the borrowing ability for urban transport is often restricted by the availability of future revenue to support the borrowing, as well as the legal framework, which can set a limit on the amount that can be borrowed without the consent of central government. The key purpose of such limits is to ensure that borrowing is affordable, although in smaller cities his may be owing to the fact that national government needs to borrow on their behalf. Grants and loans are also provided by foreign sources, e.g. in the form of official development aid (ODA). These are provided by governments of industrialised countries, either bilaterally, or through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, providing in total billions of dollars worth of transport investments every year. However, most of the funding is channeled into road building, which does not always support the goal of sustainable urban transport.

Optimally Combining the Financing Options

The various funding instruments identified in the previous sections can be combined to ensure a good coverage of the various aspects of sustainable transport, whilst achieving a high level of financial sustainability. The following points are crucial when combining the individual instruments:

- Integrating financing into a wider policy process – which includes the reform of transport prices and financial management.

- Develop a multi-tier financing system – that combines various financing approaches based on their comparative advantages, and allows both capital investments and recurrent expenditures to be fully covered.

- Consider the development of an urban transport fund – as a potential vehicle to ensure sustainable urban transport financing. Certain income sources can also be earmarked (or ring-fenced) to improve the stability and predictability of resources.

Further Information

- Further and more detailed information can be found on the homepage of the Sustainable Urban Transport Project. The Sustainable Urban Transport Project aims to help developing world cities achieve their sustainable transport goals, through the dissemination of information about international experience, policy advice, training and capacity building.

References