Difference between revisions of "Firewood Cookstoves"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) m |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | The main influencing agent for “a)” and “b)” is heat, whereas “c)” is regulated by the supply of oxygen. Find here more information and illustrating figures on pages | + | The main influencing agent for “a)” and “b)” is heat, whereas “c)” is regulated by the supply of oxygen. |

| − | + | ||

| + | Find here more information and illustrating figures on pages 14-15 in the "[[:File:Micro_Gasification_2.0_Cooking_with_gas_from_dry_biomass.pdf|Manual on Micro-gasification]]". For more information on the characteristics of firewood as a fuel see Cooking with Firewood. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ##########<br/> | ||

*More complete combustion = less emission of unburned fuel | *More complete combustion = less emission of unburned fuel | ||

*Shelter the fire | *Shelter the fire | ||

| Line 523: | Line 529: | ||

[[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium|--> Back to Overview GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium]] | [[GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium|--> Back to Overview GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Cooking_Energy_Compendium_(GIZ_HERA)]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Improved_Cooking]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Cookstoves]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Wood_Energy]] | ||

[[Category:Cooking_Energy]] | [[Category:Cooking_Energy]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 15:43, 19 December 2016

Basics | Policy Advice | Planning | Designing and Implementing (ICS Supply)| Technologies and Practices | Designing and Implementing (Woodfuel Supply)| Climate Change

Introduction

Firewood is wood from logs, sticks or twigs. It has been used as a fuel since the beginning of mankind. In principle, it is renewable and relatively easy to produce, transport and store. However, the use of firewood for cooking is commonly associated with deforestation and health problems. This is not an inherent problem of the fuel, but is strongly influenced by the quality and quantity of its correct usage and can be overcome by improving the efficiency of the wood fuel usage.

Two major factors determine if firewood burns clean and efficient: its moisture content and the oxygen supply of the fire. While it depends on the user to make sure that the fuel is dry, the air-flow depends on the stove design. In a natural draught stove, the supply of air is created by the chimney or stack height of the fuel. However, there must be a difference in temperature between the stove and the top of the chimney to generate draught. Natural draught is likely to cause incomplete combustion with higher emissions and energy losses through the chimney. Moreover, it is also difficult to regulate.

The burning of wood is a sequence of steps:

- Moisture is evaporated

- Wood decomposes into combustible wood-gas and char

- Char is converted into ash

The main influencing agent for “a)” and “b)” is heat, whereas “c)” is regulated by the supply of oxygen.

Find here more information and illustrating figures on pages 14-15 in the "Manual on Micro-gasification". For more information on the characteristics of firewood as a fuel see Cooking with Firewood.

- More complete combustion = less emission of unburned fuel

- Shelter the fire

- Direct flames to the pot

- Consume less fuel

- Emit less smoke

- Be safer

- Cook faster

- Faster and more efficient stoves require often more attention by the cook

- No mosquito repellent, no food preservation

- Less space heating

- No lighting after dark

Improve heat transfer into the cooking pot

- Position cooking pot at the hottest place of the flame;

- Hot gasses are passing close to the pot to maximize heat transfer;

- Consume less fuel

- Cook faster

- Be safer

- Stove is sometimes higher than the open fire

Households have to prioritize their needs in order to come up with the decision if an improved cook stove is suitable for them. In areas with fuel scarcity, the need for reduced fuel consumption might be ranked higher than the need for space heating or lighting after dark.

Another strategy can be to provide additional solutions to complement the introduction of the improved cook stoves:

- an extra space heater for the cold season

- a mosquito-repellent net

- a solar lantern for lighting

Stoves for firewood have been developed for over 3000 years. Overviews on types and models have been developed from various entities. Below is just a selection of these:

- UNESCO(1982): Consolidation of information. Cooking stoves Handbook

- GIZ (1995) by Westhoff/German 'Stove Images - a Documentation of Improved and Traditional Stoves in Africa, Asia and Latin America'.

The Aprovecho Institute in Oregon has analysed the design principles which can help to make firewood stoves more fuel-efficient. If all principles are applied, the result would be called a rocket stove, which was invented by Dr. Larry Winiarsky.

-> For further details see www.aprovecho.org.

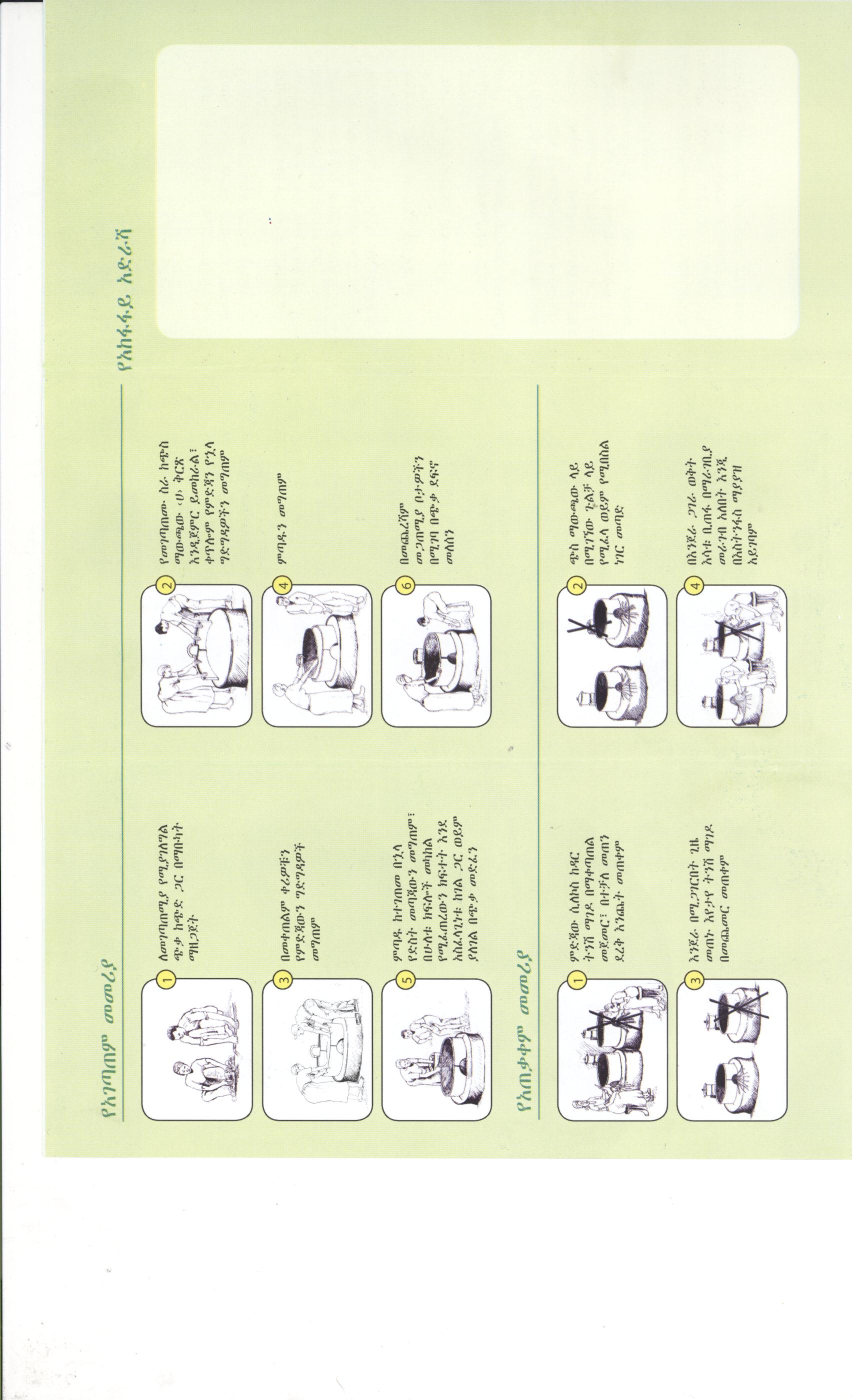

The Rocket Stove Principle

One of the most successful new concepts in stove design is the rocket stove principle.

- It has a tall combustion chamber which behaves a bit like a chimney; creating more draught than a standard stove. This assists in mixing the air, fuel particles and volatiles, resulting in a hot flame. The internal walls are insulated, reflecting all the heat back into the chamber rather than losing it to the stove body. The insulation keeps everything very hot so that the chemical reaction is more intense, whilst the tall chamber provides more time in which the gases and particles can be burnt completely, giving out all their heat and discharging mainly carbon dioxide and water vapour.

- These hot flue gases pass through a well defined gap between a ‘skirt’, and the pot, as shown in the illustrations given below, resulting in a large percentage of the heat being forced against the sides of the pot, and being transferred to the pot. Where various sizes of pot are used on the same stove, the skirt can be funnel-shaped to accommodate different pots, although some efficiency will be lost.

- An elbow-shaped combustion chamber, with a shelf for the fuel wood, supports the pre-drying of the firewood and allows a controlled, and sufficient, flow of primary air to be warmed as it passes under the wood to the burning wood tips.

| The rocket stove principle. Source: Aprovecho |

Design principles, which can be used more generally include:

- Insulation around the fire and along the entire heat flow path using lightweight, heat resistant materials

- A well-controlled, uniform draught in the burning chamber during the entire combustion process

- Use of a grate or a shelf under the firewood

- Heat transfer maximised by the insertion of the pot into the stove body or using a skirt around the pot.

| A rocket-type stove in action, and showing insulation of the burning chamber, skirt around pot and support frame. Source: GIZ / Aprovecho Institute |

All improved firewood stoves apply at least some of these aspects (listed below) geared toward increasing efficiency and improving heat transfer.

How can we improve the design of the stove to increase the combustion efficiency in a firewood stove?

| Aspect |

How to achieve |

|---|---|

| Increasing the temperature in the combustion chamber (as the burning process is temperature controlled) |

|

| Reduce the intake of firewood | Create a small entrance for the firewood. Then only the required level of wood can be entered. Excess wood cannot be supplied to the reactor |

| Burn off all the volatiles | Allow enough space in the combustion chamber (increasing the space between pot and fire) |

| Adequate air supply | Regulate air and wood intake into the combustion chamber and ensure both the amount of air and wood intake are correlated |

| Reduce the inflow of cold air | Regulate air intake (door) |

| Intake of pre-heated air | Use air as an insulated between an inner and an outer wall of the stove. Air is channeled through this gap before entering the combustion chamber |

| Increasing the draft |

|

| Increase the surface of the wood that is in contact with air |

|

How can we improve the design of the stove to improve the heat transfer in a firewood stove?

| Aspect |

How to Achieve |

|---|---|

| Raise the pot to the highest point of the flames |

|

| Force the hot air to create turbulences on the surface of the cooking pot | Create a small gap between the cooking pot and the pot rest which is big enough not to choke the fire and small enough to mix the air close to the pot. |

| Increase the surface area for the heat transfer |

Create a skirt around the pot which forces the hot air to the walls of the pot. This creates turbulences in the air around the pot surface. |

Application of the Principles

Clay Stove versus a 3-Stone Fire

|

Increased combustion efficiency:

|

|

Improved heat transfer:

|

Quite a number of improved firewood stoves which – like this simple clay stove – adhere to many of the principles mentioned above and deliver some improvements compared to the 3-stone fire. They are an entry point for households into the use of improved cook stoves as they are more affordable than the sophisticated rocket stoves.

Examples are: (see below for Factsheets)

- Chitetezo Mbaula (Malawi)

- Jiko Kisasa (Kenya)

- Tulipe (Benin)

- Anagi stove (Sri Lanka)

- VITA (Mauretanien)

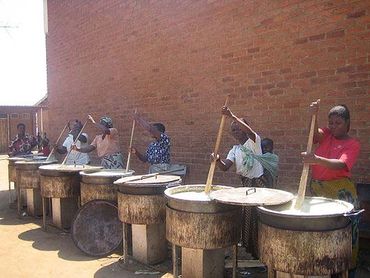

Institutional Stove Compared to an Open Fire

|

Institutional Stove Compared to an open Fire: 40 instead of 170 kg of firewood |

The considerable savings have made institutional rocket stoves very popular among school feeding programmes in Malawi (see also Ashden Award video 2006)

| School feeding programme Mary`s Meals Blantyre, Malawi |

Fixed Stoves

Today most of the GIZ-promoted high-efficiency wood stoves follow this rocket stove principle (see fact sheets for examples):

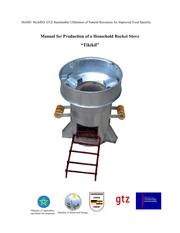

| MIRT stove for injeera baking Tikikil, Ehtiopia | |||

|

Jiko Kisasa, Kenya (2011) | |||

|

Brick Rocket Stove, Kenya (2011) |

GIZ PSDA Stoves Promotion | ||

|

Two pot mud-rocket Lorena with Air Bypass, Uganda (2011) |

Construction guide from 2008 featuring air-bypass available in English: --> Available in French

| ||

|

Two pot mud-rocket Lorena with shelf, Uganda (2011) | |||

|

One-Pot Shielded Fire Stove with shelf, Uganda (2011) | |||

|

One-Pot Shielded Fire Stove with bypass air inlet, Uganda (2011) | |||

|

Fixed One-Pot Rocket Mud Stove, Benin, Uganda (2011) | |||

| Esperanza stove, Malawi | |||

|

Malawi Institutional Brick Rocket Stove, Malawi (2008) | |||

|

Inkawasi Stoves in Peru (various models adapated for different regions and materials):

| |||

|

Manual Uso y Mantenimiento de la Eco-Estufa Justa, Honduras (2011) | |||

|

Manual Construyendo la Eco-Estufa Justa 16 x 24, Honduras (2011) | |||

Portable Stoves

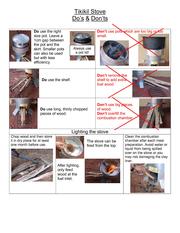

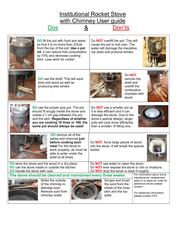

Efficient, smoke-free cooking with the Rocket Stove:

Further Information

Aprovecho Research Center

For almost 30 years, Aprovecho Research Center (ARC) consultants have been designing and implementing improved biomass cooking and heating technologies in more than 60 countries worldwide. Their website provides a wealth of useful information including construction materials.

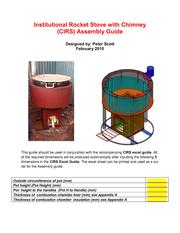

Design Tool for Constructing an Institutional Rocket Stove with Chimney

With funding from GIZ HERA, Rocket Stove.org and Prakti Design Lab have developed a new automated tool that allows users to build a customized institutional rocket stove. The tool can be used to design a brick or metal institutional rocket stove with or without chimney for any institutional pot (30 L + capacity).

The stove options for this tool are:

- a fixed brick stove (w/out chimney)

- a portable metal stove with square combustion chamber (w/out chimney)

- a portable metal stove with circular combustion chamber (with chimney)

-> http://www.rocketstove.org/

Rocket Stove Principle

An animation showing the rocket stove principle can be found here.

New Wood Fuel Stove Designs

Two major factors determine if woodfuels burn clean and efficient: its dryness and ventilation. Hence, the right amount of air on the right spot is necessary during the process to ensure a complete combustion.

While it depends on the user to make sure that the fuel is dry, the air-flow depends on the stove design. In a natural draught stove, the movement of air is created by the chimney or stack height of the fuel. However, there must be a difference in temperature between the stove and the top of the chimney to generate draught. Natural draught is likely to cause incomplete combustion with higher emissions and energy losses through the chimney. Moreover, it is also difficult to regulate.

Wood Fuel Stoves with Forced Convection

Instead of naturally ‘pulling’ air through a stove by stack height, fans or blowers are useful to ‘push’ air into the combustion chamber. This enhances a good air-fuel mix and thus, more complete combustion. Electricity is the most convenient power source to create a forced air-flow. It can be provided by batteries or, if available, through the grid. Recently, thermo-electric generators (TEG) have been developed to power fans in stoves. They use the temperature differences within the stove to generate electricity. Though TEGs have great potential to provide power to other applications (LEDs, cell phone charging) as well, they are still in their infancy. Forced convection can reduce emissions of stoves by up to 90 %, thus alleviating IAP levels. More test results from more widespread use are expected soon.

Models Developed by Others

- Stovetec: http://www.stovetec.net/us/stove-models

- Envirofit: http://www.envirofit.org/

- BioLite: http://www.biolitestove.com/Technology.html

References

This article was originally published by GIZ HERA. It is basically based on experiences, lessons learned and information gathered by GIZ cook stove projects. You can find more information about the authors and experts of the original “Cooking Energy Compendium” in the Imprint.