Knowledge fuels change

For over a decade, Energypedia has shared free, reliable energy expertise with the world.

We’re now facing a serious funding gap.

Help keep this platform alive — your donation, big or small, truly matters!

Thank you for your support

Difference between revisions of "The Economics of Renewable Energy"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) m (→Introduction) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Portal:Financing and Funding|► Back to Financing & Funding Portal]] | [[Portal:Financing and Funding|► Back to Financing & Funding Portal]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | = Overview = | |

| − | + | In order to assess how [[Portal:Financing and Funding|private investment]] in <span data-scaytid="1" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span> can be increased, it is necessary to understand the economics of renewable energy. | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | = A Case for <span data-scaytid="7" data-scayt_word="Renewables">Renewables</span> = | |

| − | + | Worldwide more energy is required to enable economic development. Fossil fuels are a finite resource that contribute to climate change and cause other problems like smog, extended supply lines and vulnerable power grids. Utilizing <span data-scaytid="2" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span> would help to avoid these problems, create new job opportunities and reduce the drain on hard currency for poorer countries. Because conventional fuels have received long-term subsidies in the past, it is vital that governments support the development of <span data-scaytid="3" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span> in the form of financial incentives that can create a level playing field <ref>United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), 2004. CEO briefing - Renewable Energy, Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI).</ref>. | |

| + | |||

| + | According to <span data-scaytid="12" data-scayt_word="REN-21’s">REN-21’s</span> <span data-scaytid="10" data-scayt_word="Renewables">Renewables</span> Global Futures Report 2013, the future of renewable energy is uncertain as finance remains a key challenge. The future of the <span data-scaytid="6" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span> industry depends on finance, risk-return profiles, business models, investment lifetimes and a host of other economic, policy and social factors. Many new sources of finance are possible such as insurance funds, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds along with new mechanisms for financial risk mitigation. Many new business models are also possible for local energy services, utility services, transport, community and cooperative ownership, and rural energy services <ref>Appleyard, D., March 2013. The Future of Renewables: Economic, Policy and Social Impications - Renewable Energy World International. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2013/03/from-the-editor20</ref>. | ||

[[File:Economics of RE 1.PNG|thumb|right|300px|Investments in Renewables in 2012. Source: Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance]] | [[File:Economics of RE 1.PNG|thumb|right|300px|Investments in Renewables in 2012. Source: Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance]] | ||

| + | <div></div> | ||

| + | In 2011, the global investment in renewable power and fuels increased by 17% to a new record of $257 billion dollars. Significantly, developing economies made up 35% of this total investment <ref>Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance, 2012. Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2012, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance.</ref>. | ||

<div> | <div> | ||

| − | Despite these trends, RETs continue to face a number of barriers <ref>These barriers can be financial and economically such as, higher upfront costs, political and regulatory (generally policies do not favour renewable technologies), environmental and social (e.g. planning objections), technical (e.g. intermittent nature of renewable technologies), or related to the scale of the projects, mainly higher transaction costs. To create a level playing field for renewable technologies, all the barriers mentioned above need to be addressed, but the crucial starting point is a supportive and stable policy and regulatory framework. This will encourage greater investment on the part of financial institutions. (United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), 2004)</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em; font-size: 0.85em;">.</span> | + | Despite these trends, <span data-scaytid="16" data-scayt_word="RETs">RETs</span> continue to face a number of barriers <ref>These barriers can be financial and economically such as, higher upfront costs, political and regulatory (generally policies do not favour renewable technologies), environmental and social (e.g. planning objections), technical (e.g. intermittent nature of renewable technologies), or related to the scale of the projects, mainly higher transaction costs. To create a level playing field for renewable technologies, all the barriers mentioned above need to be addressed, but the crucial starting point is a supportive and stable policy and regulatory framework. This will encourage greater investment on the part of financial institutions. (United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), 2004)</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em; font-size: 0.85em;">.</span> |

| − | When assessing decisions to support RET’s, policy-makers need to answers to the following questions, which are not alwys easy to answer:<br/> | + | When assessing decisions to support RET’s, policy-makers need to answers to the following questions, which are not <span data-scaytid="17" data-scayt_word="alwys">alwys</span> easy to answer:<br/> |

| − | #Are renewables more expensive that fossil fuels?<br/> | + | #Are <span data-scaytid="15" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span> more expensive that fossil fuels?<br/> |

| − | #Can renewables be made available on a scale large enough to replace fossil fuels? | + | #Can <span data-scaytid="19" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span> be made available on a scale large enough to replace fossil fuels? |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 26: | Line 29: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | < | + | = <span style="font-size: 19px; line-height: 23px;">Costs of Renewable Energy</span> = |

| − | < | + | Generally the economics of renewable energy are not competitive, as production costs per unit of energy are usually higher than those for fossil fuels as depicted in the figure below, which shows the relative costs for renewable energy technologies compared with each other, and with non-renewable energy<ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. |

| − | + | [[File:Economics of RE 2.PNG|thumb|right|400px|Relative costs for renewable energy technologies compared with each other, and with non-renewable energy. Source: Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As shown in the figure, while non-renewable costs are found in the range of US$0.3–US$0.10/<span data-scaytid="22" data-scayt_word="KwH">KwH</span> (kilowatt hour), most <span data-scaytid="21" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span> are '''more expensive''' and have a far '''greater cost range'''. This indicates the relative maturity of technologies and also the key significant '''cost difference of renewable energy production''' (which is dependent on factors such as wind speed and degrees of solar intensity.)<br/> | |

| − | + | '''Scale '''is also an important issue. This is due to the fact that fossil-fuel technologies have been developed, improved and manufactured on an increasing scale for a century. This is not yet the case for <span data-scaytid="24" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span><ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em; font-size: 0.85em;">.</span> | |

| − | + | These factors suggest that there is scope to reduce the varying production costs of <span data-scaytid="26" data-scayt_word="renewables">renewables</span>.<span style="font-size: 0.85em; line-height: 1.5em;"></span> | |

| − | + | *The most expensive form of renewable energy is [[Portal:Hydro|ocean/tidal electricity]], which, even at the bottom of the potential cost range, remains uncompetitive with fossil fuels.<br/> | |

| − | + | *The next is [[Portal:Solar|solar power]], which at its cheapest is potentially competitive with fossil fuels. However, its midrange costs are well above fossil fuels. This wide range reflects the cost implications of different technologies. For example, large-scale'''Concentrated Solar Power (<span data-scaytid="30" data-scayt_word="CSP">CSP</span>)''' techniques employed in a desert environment could produce electricity at a far lower cost than small solar panels fitted to residential properties.<br/> | |

| + | *[[Portal:Wind|Wind power]] can be cheaper, but remains more expensive than fossil fuels in most instances. This range reflects differing scales of energy generation, but also the different cost structures of onshore and offshore wind.<br/> | ||

| + | *[[Portal:Bioenergy|Biomass]], [[Geothermal Energy|geothermal]] and [[Portal:Hydro|hydropower]] in particular are already competitive with fossil fuels in some circumstances <ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 48: | Line 49: | ||

=== Costs of Fossil Fuels === | === Costs of Fossil Fuels === | ||

| − | + | Costs relative to fossil fuels are also important particularly because: | |

| − | + | '''1. Fossil-fuel energy does not reflect its full social costs. '''<br/> | |

| + | *Climate change has been described as the "biggest market failure in history" (Stern Review, 2006) because the environmental costs associated with carbon emissions are not included in market prices.<br/> | ||

| + | *Furthermore, fossil fuels are [[Subsidies|subsidized]] for about US$300 billion per year. Removing theses subsidies and incorporating externalities into fossil fuel costs would dramatically change relative costs<ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | ||

| − | + | '''2. It is more expensive to deliver non-renewable energy in some places than others.'''<br/> | |

| − | + | *For example, rural communities in developing countries are often not connected to the grid, resulting in "off-grid" energy production - particularly solar power - being more competitive<ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''3. There is no shortage of renewable energy potential at the global level '''(See figure below).<br/> | |

| + | *In terms of primary energy, it is already technically possible to generate many multiples of global energy supply using solar energy. There is also an abundant supply of wind or geothermal power to meet all of today’s global electricity demand<ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>.[[File:Economics of RE 3.PNG|thumb|right|500px|Ranges of global technical potentials of RE sources]] | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <br/> | + | It is significant that much of the global solar power is concentrated in developing countries, although other areas also have a high potential. <br/> |

| − | <br/> | + | The table below shows the top 10 countries globally in terms of renewable energy potential relative to energy use.<br/> |

| + | They are all developing countries, which reflects their relatively low energy use at present, but also the relative abundance of solar, wind, hydro and geothemal energy<ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em; font-size: 0.85em;">.</span> | ||

| + | </div><div><span style="line-height: 20.390625px;"></span> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | + | [[File:Economics of RE 4.PNG|thumb|right|180px|Top ten countries globally in terms of renewable energy potential relative to energy use.]] | |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 88: | Line 91: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | == | + | = <span style="font-size: 22px; line-height: 30px;">Increasing the Use of Renewable Energy</span> = |

It is therefore clear that there is significant scope to increase the use of renewable energy in developing countries. This is not limitless, however. Although we can expect the costs of renewable energy to continue to fall relative to fossil fuels, particularly in countries with high renewable energy potential, fossil fuels are likely to retain a cost advantage in most cases<ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | It is therefore clear that there is significant scope to increase the use of renewable energy in developing countries. This is not limitless, however. Although we can expect the costs of renewable energy to continue to fall relative to fossil fuels, particularly in countries with high renewable energy potential, fossil fuels are likely to retain a cost advantage in most cases<ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 97: | ||

Two important conclusions can be drawn from this. First, the basic economics of renewable energy need to be artificially altered, either by increasing the cost of fossil fuel-based energy (e.g. through taxes or equivalent mechanisms), or by reducing the costs of renewable energy (e.g. subsidies), or by boosting the returns to renewable energies (e.g. through paying a premium for this form of energy) <ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | Two important conclusions can be drawn from this. First, the basic economics of renewable energy need to be artificially altered, either by increasing the cost of fossil fuel-based energy (e.g. through taxes or equivalent mechanisms), or by reducing the costs of renewable energy (e.g. subsidies), or by boosting the returns to renewable energies (e.g. through paying a premium for this form of energy) <ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | ||

| − | Second, it does not follow that developing countries should be required to meet these costs.<br/>Where it is the case that employing renewable technologies makes economic sense, this is not an issue – only limited incentives are needed and it is reasonable to expect them to be met domestically because of the benefits that will accrue to the country. However, where the development of renewable energy capacity could place countries at a competitive disadvantage and/or these countries bear no responsibility for climate change, the costs should be met by countries that do bear such a responsibility. This case is even stronger while developed countries are subsidising fossil-fuel energy <ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. | + | Second, it does not follow that developing countries should be required to meet these costs.<br/>Where it is the case that employing renewable technologies makes economic sense, this is not an issue – only limited incentives are needed and it is reasonable to expect them to be met domestically because of the benefits that will accrue to the country. However, where the development of renewable energy capacity could place countries at a competitive disadvantage and/or these countries bear no responsibility for climate change, the costs should be met by countries that do bear such a responsibility. This case is even stronger while developed countries are <span data-scaytid="36" data-scayt_word="subsidising">subsidising</span> fossil-fuel energy <ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. |

| − | This suggests that, in most cases, low-income countries (LICs) should generally not be expected to subsidise the development of a renewable energy sector. Significant implications result from this, which we shall return to throughout this paper <ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>.<br/> | + | This suggests that, in most cases, low-income countries (<span data-scaytid="37" data-scayt_word="LICs">LICs</span>) should generally not be expected to <span data-scaytid="38" data-scayt_word="subsidise">subsidise</span> the development of a renewable energy sector. Significant implications result from this, which we shall return to throughout this paper <ref>Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf</ref>. |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| − | |||

= Further Information = | = Further Information = | ||

Revision as of 14:25, 8 July 2013

► Back to Financing & Funding Portal

Overview

In order to assess how private investment in renewables can be increased, it is necessary to understand the economics of renewable energy.

A Case for Renewables

Worldwide more energy is required to enable economic development. Fossil fuels are a finite resource that contribute to climate change and cause other problems like smog, extended supply lines and vulnerable power grids. Utilizing renewables would help to avoid these problems, create new job opportunities and reduce the drain on hard currency for poorer countries. Because conventional fuels have received long-term subsidies in the past, it is vital that governments support the development of renewables in the form of financial incentives that can create a level playing field [1].

According to REN-21’s Renewables Global Futures Report 2013, the future of renewable energy is uncertain as finance remains a key challenge. The future of the renewables industry depends on finance, risk-return profiles, business models, investment lifetimes and a host of other economic, policy and social factors. Many new sources of finance are possible such as insurance funds, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds along with new mechanisms for financial risk mitigation. Many new business models are also possible for local energy services, utility services, transport, community and cooperative ownership, and rural energy services [2].

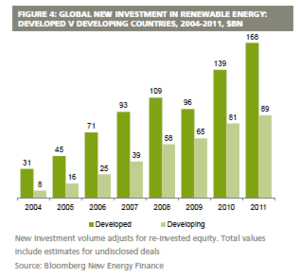

In 2011, the global investment in renewable power and fuels increased by 17% to a new record of $257 billion dollars. Significantly, developing economies made up 35% of this total investment [3].

Despite these trends, RETs continue to face a number of barriers [4].

When assessing decisions to support RET’s, policy-makers need to answers to the following questions, which are not alwys easy to answer:

- Are renewables more expensive that fossil fuels?

- Can renewables be made available on a scale large enough to replace fossil fuels?

Costs of Renewable Energy

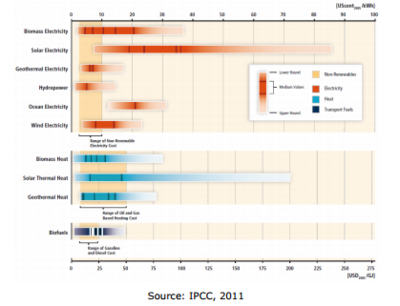

Generally the economics of renewable energy are not competitive, as production costs per unit of energy are usually higher than those for fossil fuels as depicted in the figure below, which shows the relative costs for renewable energy technologies compared with each other, and with non-renewable energy[5].

As shown in the figure, while non-renewable costs are found in the range of US$0.3–US$0.10/KwH (kilowatt hour), most renewables are more expensive and have a far greater cost range. This indicates the relative maturity of technologies and also the key significant cost difference of renewable energy production (which is dependent on factors such as wind speed and degrees of solar intensity.)

Scale is also an important issue. This is due to the fact that fossil-fuel technologies have been developed, improved and manufactured on an increasing scale for a century. This is not yet the case for renewables[6].

These factors suggest that there is scope to reduce the varying production costs of renewables.

- The most expensive form of renewable energy is ocean/tidal electricity, which, even at the bottom of the potential cost range, remains uncompetitive with fossil fuels.

- The next is solar power, which at its cheapest is potentially competitive with fossil fuels. However, its midrange costs are well above fossil fuels. This wide range reflects the cost implications of different technologies. For example, large-scaleConcentrated Solar Power (CSP) techniques employed in a desert environment could produce electricity at a far lower cost than small solar panels fitted to residential properties.

- Wind power can be cheaper, but remains more expensive than fossil fuels in most instances. This range reflects differing scales of energy generation, but also the different cost structures of onshore and offshore wind.

- Biomass, geothermal and hydropower in particular are already competitive with fossil fuels in some circumstances [7].

Costs of Fossil Fuels

Costs relative to fossil fuels are also important particularly because:

1. Fossil-fuel energy does not reflect its full social costs.

- Climate change has been described as the "biggest market failure in history" (Stern Review, 2006) because the environmental costs associated with carbon emissions are not included in market prices.

- Furthermore, fossil fuels are subsidized for about US$300 billion per year. Removing theses subsidies and incorporating externalities into fossil fuel costs would dramatically change relative costs[8].

2. It is more expensive to deliver non-renewable energy in some places than others.

- For example, rural communities in developing countries are often not connected to the grid, resulting in "off-grid" energy production - particularly solar power - being more competitive[9].

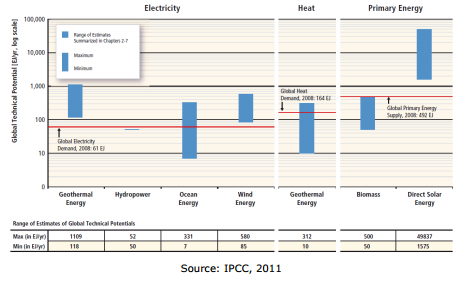

3. There is no shortage of renewable energy potential at the global level (See figure below).

- In terms of primary energy, it is already technically possible to generate many multiples of global energy supply using solar energy. There is also an abundant supply of wind or geothermal power to meet all of today’s global electricity demand[10].

It is significant that much of the global solar power is concentrated in developing countries, although other areas also have a high potential.

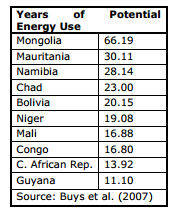

The table below shows the top 10 countries globally in terms of renewable energy potential relative to energy use.

They are all developing countries, which reflects their relatively low energy use at present, but also the relative abundance of solar, wind, hydro and geothemal energy[11].

Increasing the Use of Renewable Energy

It is therefore clear that there is significant scope to increase the use of renewable energy in developing countries. This is not limitless, however. Although we can expect the costs of renewable energy to continue to fall relative to fossil fuels, particularly in countries with high renewable energy potential, fossil fuels are likely to retain a cost advantage in most cases[12].

Two important conclusions can be drawn from this. First, the basic economics of renewable energy need to be artificially altered, either by increasing the cost of fossil fuel-based energy (e.g. through taxes or equivalent mechanisms), or by reducing the costs of renewable energy (e.g. subsidies), or by boosting the returns to renewable energies (e.g. through paying a premium for this form of energy) [13].

Second, it does not follow that developing countries should be required to meet these costs.

Where it is the case that employing renewable technologies makes economic sense, this is not an issue – only limited incentives are needed and it is reasonable to expect them to be met domestically because of the benefits that will accrue to the country. However, where the development of renewable energy capacity could place countries at a competitive disadvantage and/or these countries bear no responsibility for climate change, the costs should be met by countries that do bear such a responsibility. This case is even stronger while developed countries are subsidising fossil-fuel energy [14].

This suggests that, in most cases, low-income countries (LICs) should generally not be expected to subsidise the development of a renewable energy sector. Significant implications result from this, which we shall return to throughout this paper [15].

Further Information

- Economic and Financial Impacts of Grid Interconnections

- Economic Viability of a Biogas Plant

- Economic Analyses of Wind Energy Projects

- Assessing the Economic Viability of Business Ideas for Productive Use

- Macro-economic evaluation of Biogas Plants

- Socio-economic and Environmental Impacts of MHP

- Subsidies

- Overview Costs and Benefits of Energy Development Projects

References

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), 2004. CEO briefing - Renewable Energy, Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI).

- ↑ Appleyard, D., March 2013. The Future of Renewables: Economic, Policy and Social Impications - Renewable Energy World International. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2013/03/from-the-editor20

- ↑ Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance, 2012. Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2012, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance.

- ↑ These barriers can be financial and economically such as, higher upfront costs, political and regulatory (generally policies do not favour renewable technologies), environmental and social (e.g. planning objections), technical (e.g. intermittent nature of renewable technologies), or related to the scale of the projects, mainly higher transaction costs. To create a level playing field for renewable technologies, all the barriers mentioned above need to be addressed, but the crucial starting point is a supportive and stable policy and regulatory framework. This will encourage greater investment on the part of financial institutions. (United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), 2004)

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf

- ↑ Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. [Online]fckLRAvailable at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf