Difference between revisions of "Mobile Phone Market in Kenya"

From energypedia

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| + | [[File:Summary Statistics of Mobile Phone Use in Kenya.png|left|300px]] | ||

| − | |||

| + | |||

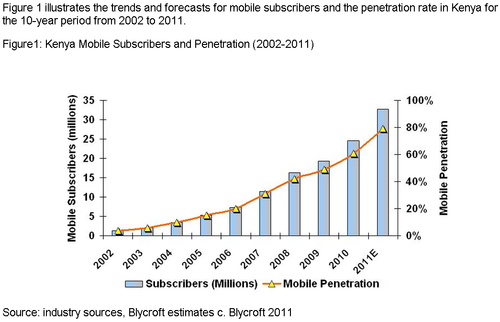

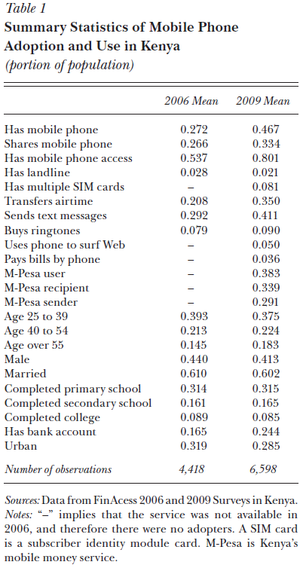

| + | <div>Monile Service provider Safaricom projected that the mobile phone market in Kenya</div><div>would reach three million subscribers by 2020. The price of the cheapest mobile phone</div><div>in Kenya costs half the average monthly income. Using firm-level data from</div><div>the World Bank Enterprise Surveys for Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, we fifi nd that</div><div>a large percentage of fifi rms had already adopted mobile phones in 2003, ranging</div><div>from 83 to 93 percent across these countries. This high level of adoption appears</div><div>to be correlated with the poor quality of landline services. Kenyan</div><div>firms reported an average of 36 days of interrupted landline service per year, with</div><div>interruptions lasting an average of 37 hours.<br/></div><div><br/></div><div>Many fifi rms also faced challenges in even obtaining landline service.</div><div>On average, Kenyan fifi rms had to wait 100 days to obtain landline service, with a</div><div>majority of fifi rms paying bribes to facilitate this connection. (The average bribe was</div><div>reported to be worth US$117, compared with a GDP per capita of US$780). Thus,</div><div>explicit and implicit landline costs could have provided powerful incentives for</div><div>fifi rms to adopt mobile phones.</div><div><br/></div><div>While Kenyan firms rapidly adopted mobile phones, the individual adoption</div><div>rate has been signifificantly lower. Using data from the FinAccess surveys, we examine</div><div>some basic patterns of individual mobile phone adoption in Kenya. Between 2006</div><div>and 2009, the percentage of the Kenyan population with mobile phone coverage</div><div>remained relatively static, but the number of subscriptions tripled—reaching</div><div>17 million by 2009 (GSMA data for 2009). The adoption of mobile phone handsets</div><div>increased by 74 percent during this period, from 27 percent in 2006 to 47 percent</div><div>in 2009, as shown in Table 1. One-third of Kenyans shared their mobile phones</div><div>with friends or relatives, supporting qualitative evidence of free riding and the use</div><div>of mobile phones as a common property resource in sub-Saharan Africa. At the</div><div>same time, such patterns could also reflfl ect cost-sharing, especially among poorer</div><div>rural households for whom the cost of handsets and services is still prohibitively</div><div>expensive. For these reasons, reported data on mobile phone subscriptions could</div><div>signififi cantly underestimate the number of mobile phone users; in fact, while only</div><div>47 percent of individuals owned a phone, 80 percent reported having access to a</div><div>mobile phone through direct ownership or sharing.<br/></div><div><br/></div><div>How Mobile Phones Can Generate Additional Employment</div><div>One of the most direct economic impacts of mobile phones in Africa is through</div><div>job creation. With an increase in the number of mobile phone operators and</div><div>greater mobile phone coverage, labor demand within these sectors has increased.</div><div>For example, formal sector employment in the private transport and communications</div><div>sector in Kenya rose by 130 percent between 2003 and 2007 (CCK, 2008),</div><div>suggesting that mobile phones have contributed to job creation.</div><div><br/></div><div>The mobile phone sector has also spawned a wide variety of business and</div><div>entrepreneurship opportunities in the informal sector. While we would expect job</div><div>creation in any new growth sector, many of these employment opportunities are</div><div>directly related to the specififi c business strategies of mobile phone companies in</div><div>Africa. For example, because most Africans use prepaid phones (or “pay as you</div><div>go”), mobile phone companies had to create extensive phone credit distribution</div><div>networks in partnership with the formal and informal sector.8 Thus, small</div><div>shops that have traditionally sold dietary staples and soap now sell mobile phone</div><div>credit (airtime), particularly in small denominations. Young men and women are</div><div>often found selling airtime cards in the streets. Numerous small-scale (and often</div><div>informal) fifi rms have also opened shops to sell, repair, and charge mobile phone</div><div>handsets, either using car batteries or small generators. In the early years of mobile</div><div>phone usage, entrepreneurial individuals started businesses to rent mobile phones,</div><div>especially in rural areas.<ref name="Mobile Phones and Economic Development in Africa">http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.24.3.207</ref></div> | ||

Revision as of 08:49, 28 March 2012

Monile Service provider Safaricom projected that the mobile phone market in Kenya

would reach three million subscribers by 2020. The price of the cheapest mobile phone

in Kenya costs half the average monthly income. Using firm-level data from

the World Bank Enterprise Surveys for Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, we fifi nd that

a large percentage of fifi rms had already adopted mobile phones in 2003, ranging

from 83 to 93 percent across these countries. This high level of adoption appears

to be correlated with the poor quality of landline services. Kenyan

firms reported an average of 36 days of interrupted landline service per year, with

interruptions lasting an average of 37 hours.

Many fifi rms also faced challenges in even obtaining landline service.

On average, Kenyan fifi rms had to wait 100 days to obtain landline service, with a

majority of fifi rms paying bribes to facilitate this connection. (The average bribe was

reported to be worth US$117, compared with a GDP per capita of US$780). Thus,

explicit and implicit landline costs could have provided powerful incentives for

fifi rms to adopt mobile phones.

While Kenyan firms rapidly adopted mobile phones, the individual adoption

rate has been signifificantly lower. Using data from the FinAccess surveys, we examine

some basic patterns of individual mobile phone adoption in Kenya. Between 2006

and 2009, the percentage of the Kenyan population with mobile phone coverage

remained relatively static, but the number of subscriptions tripled—reaching

17 million by 2009 (GSMA data for 2009). The adoption of mobile phone handsets

increased by 74 percent during this period, from 27 percent in 2006 to 47 percent

in 2009, as shown in Table 1. One-third of Kenyans shared their mobile phones

with friends or relatives, supporting qualitative evidence of free riding and the use

of mobile phones as a common property resource in sub-Saharan Africa. At the

same time, such patterns could also reflfl ect cost-sharing, especially among poorer

rural households for whom the cost of handsets and services is still prohibitively

expensive. For these reasons, reported data on mobile phone subscriptions could

signififi cantly underestimate the number of mobile phone users; in fact, while only

47 percent of individuals owned a phone, 80 percent reported having access to a

mobile phone through direct ownership or sharing.

How Mobile Phones Can Generate Additional Employment

One of the most direct economic impacts of mobile phones in Africa is through

job creation. With an increase in the number of mobile phone operators and

greater mobile phone coverage, labor demand within these sectors has increased.

For example, formal sector employment in the private transport and communications

sector in Kenya rose by 130 percent between 2003 and 2007 (CCK, 2008),

suggesting that mobile phones have contributed to job creation.

The mobile phone sector has also spawned a wide variety of business and

entrepreneurship opportunities in the informal sector. While we would expect job

creation in any new growth sector, many of these employment opportunities are

directly related to the specififi c business strategies of mobile phone companies in

Africa. For example, because most Africans use prepaid phones (or “pay as you

go”), mobile phone companies had to create extensive phone credit distribution

networks in partnership with the formal and informal sector.8 Thus, small

shops that have traditionally sold dietary staples and soap now sell mobile phone

credit (airtime), particularly in small denominations. Young men and women are

often found selling airtime cards in the streets. Numerous small-scale (and often

informal) fifi rms have also opened shops to sell, repair, and charge mobile phone

handsets, either using car batteries or small generators. In the early years of mobile

phone usage, entrepreneurial individuals started businesses to rent mobile phones,

especially in rural areas.[2]