Difference between revisions of "Low Carbon Transport & Green Growth"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Portal:Mobility|►Back to Mobility Portal]]<br/> | ||

= Overview = | = Overview = | ||

| Line 73: | Line 75: | ||

== Urban Transport Policies or Programmes == | == Urban Transport Policies or Programmes == | ||

| − | A third key measure is enabling local and urban authorities to advance low-carbon transportation. This is especially important when it comes to investments in low-carbon infrastructure. The major challenge that faces urban policy-makers is to [[ | + | A third key measure is enabling local and urban authorities to advance low-carbon transportation. This is especially important when it comes to investments in low-carbon infrastructure. The major challenge that faces urban policy-makers is to [[Financing Sustainable Urban Transport|finance a sustainable urban transport system]] and ensure sustainable funding in the long-term. By providing the necessary financial resources for investment and institutional building, the capacity to raise and manage funding at the local level can be build up and the fragmentation of responsibilities amongst the relevant (transport) authorities can be defeated. |

Under this principle national transportation funds can be dedicated at a much larger scale to public transport, bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. A sustainable urban transport policy or program systematically supports cities to invest in low carbon transport systems. Funding is usually related to some conditions, e.g. earmarked for specific measures or the preparation of a comprehensive integrated transport plan<ref name="D. Bongardt, M. Breithaupt, F. Creutzig 2011, Beyond the Fossil City: Towards low Carbon Transport and Green Growth, Eschborn, Germany">D. Bongardt, M. Breithaupt, F. Creutzig 2011, Beyond the Fossil City: Towards low Carbon Transport and Green Growth, Eschborn, Germany</ref>. | Under this principle national transportation funds can be dedicated at a much larger scale to public transport, bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. A sustainable urban transport policy or program systematically supports cities to invest in low carbon transport systems. Funding is usually related to some conditions, e.g. earmarked for specific measures or the preparation of a comprehensive integrated transport plan<ref name="D. Bongardt, M. Breithaupt, F. Creutzig 2011, Beyond the Fossil City: Towards low Carbon Transport and Green Growth, Eschborn, Germany">D. Bongardt, M. Breithaupt, F. Creutzig 2011, Beyond the Fossil City: Towards low Carbon Transport and Green Growth, Eschborn, Germany</ref>. | ||

| Line 111: | Line 113: | ||

<references /><br/> | <references /><br/> | ||

| + | [[Category:Mobility]] | ||

[[Category:Transport]] | [[Category:Transport]] | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 08:41, 20 August 2014

Overview

While transportation is crucial to the economy and individuals, as a sector it is also a significant source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and can affect human welfare negatively. Transport is currently responsible for 13% of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide and 23% of global carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) from fuel combustion are transport related. Transport related CO2 emissions are expected to increase by 57% worldwide in the period 2005 – 2030, much more than emissions from other sector. But there is consensus in science and politics that global GHG emissions have to be reduced by more than 80% by 2050 from 1990 levels in order to avoid catastrophic global warming. When contrasting the current growth rate of transport-related emissions with aspired reduction targets, it is obvious, that the transport sector needs to start contributing to mitigation efforts now.

Barriers for Low-carbon Transport

Low-carbon transport is confronted with a number of barriers that need to be encountered by strategic action. These barriers are:

- Time-lag between decisions and effects: Some measures require a long-term approach that only takes effect when continuity in political decision-making is achieved.

- Cross-cutting nature of transport: Many decisions in other sectors influence transport demand. Integrated decision-making is needed.

- Fragmented target group: Everybody and all social groups demand on mobility. The sources of emissions are rather small, so there I a need to bundle measures.

Current models of development promote the automobile as a symbol of well-being and societal advance. Unfortunately, this so-called ‘American way of life’ is doomed to fail in times of increasing resource and oil scarcity. At the moment, many industrialised countries struggle to overcome the car-dependency and face strong difficulties to turn back, while an increasing number of industrialised cities are in the process of breaking the trend. In light of this experience, it becomes even more important for developing countries to not end up in the same trap but choose a more sustainable path[1].

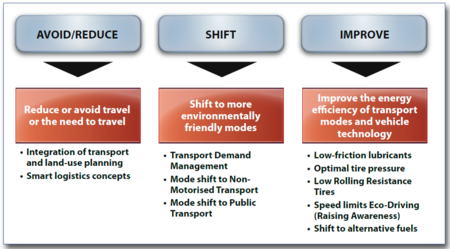

Towards Low-Carbon Transport: Avoid/Reduce – Shift – Improve

Ambitious emission reduction targets can best be reached when all factors simultaneously contribute to mitigation. A low-carbon transportation system needs more than a piecemeal approach and requires improvement in all dimensions – travel demand, mode choice, and technology – simultaneously to quickly gain traction.

A main framework for strategic action is the so-called Avoid/Reduce-Shift-Improve approach, where infrastructure is provided in such a way that:

- Future travel demand is reduced or avoided;

- Travel is shifted to more economic and environmentally-friendly modes;

- Technological measures improve the vehicle fleet and fuels.

Such a coherent approach has the potential to contribute to emission reductions beyond current expectations. It also would transcend current piecemeal measures such as introducing a few but very expensive hydrogen buses. Instead, sector-wide policies and city-wide schemes can achieve reasonable scales.

By enabling a less car-dependent mobility, developing countries can successfully avoid the high-level of car-dependency and carbon-lock-in syndromes in politics and society.

For changing the paradigm there are three relevant time-frames.

- A short term time-frame is related to immediate behavioral changes. For example, one can economise on the number of trips and do most errands in one round. Such behavioural changes are mostly induced by price signals and informative measures.

- A medium time-frame addresses vehicle technology. It is determined by the life span of automobiles, the speed of phase-in and the percentage of ‘efficient’ cars bought in a specific year. Altogether, this time-span is approximately 10-15 years.

- A long time-scale is determined by infrastructure decisions. For example, peripheral land can be developed into low-density suburbia, or clearly structured with peri-centres, semi-autonomous services, shopping infrastructures and mass rapid transit systems[1].

Policy Packages for Sustainable Development

In many cases, policy packages or sets of measures produce considerably synergies that lead to an overall effect that goes beyond the sum of their singular impacts. Sustainable transport policies consist not only of a set of measures but also target a coherent set of goals. Climate change is crucial for many Asian cities, as their Himalayan water supplies melt away or they face the danger of rising sea-levels, floods or droughts. However, in many cities, climate change is not the most relevant issue in the short-term[1].

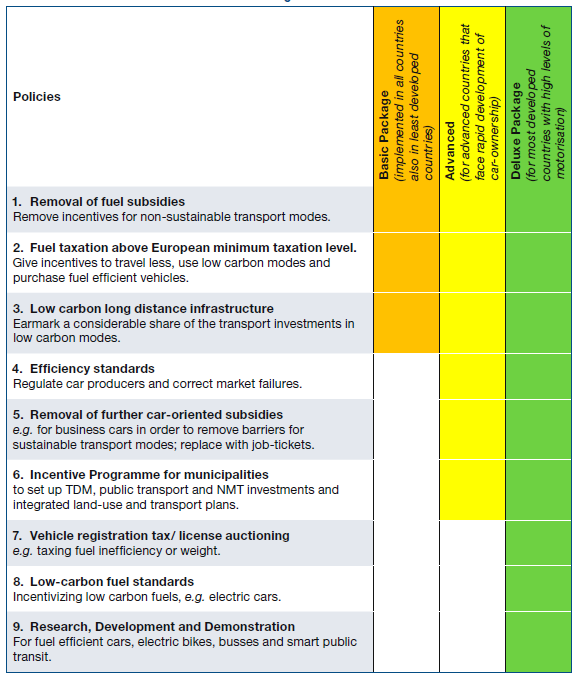

The National Policy Packages

National governments can implement direct measures and enable local low-carbon policies. The spectrum of possible policies is displayed in the table below and structured along three policy packages. They are built on each other and demonstrate a step by step development of a sustainable transport policy. However, it must be noted that each single policy needs to evolve over time and should be adapted to the stage of development.

The idea of the basic package is to remove the factors that trigger car-use and start the development of low carbon infrastructure so that shifting to the environmentally friendly and sustainable modes and practices meets also economically interests.

Rapidly developing countries that face a strong increase in car-ownership, need to tackle the growing emissions also by involving the vehicle manufacturers. In the advanced package this features is added through fuel economy standards.

For most developed countries with high levels of motorisation the deluxe package allows further reduction. This includes high taxation for fuels as well as vehicles and investments in new technology and research. However, countries have to make sure that measures, described in the other packages, are effectively implemented, as each package builds on the previous steps[1].

Fuel Prices

An increase in fuel prices has the most immediate effect on car use. Appropriate fuel pricing is an effective energy conservation and emission reduction strategy. Implementation costs are minimal, since most jurisdictions already collect fuel taxes. The petroleum industry argues that an increase in fuel taxes harms the economy, a claim that cannot be substantiated. These costs are primarily economic transfers within the economy, since increased costs to motorists are offset by increased revenues or reductions in other taxes. Higher energy taxes reduce the dependency of petroleum-consuming nations on petroleum producers. They also motivate business to become less transport intensive, more efficient and increase innovation and overall productivity, while low energy prices encourage wasteful use of resources, which is overall harmful to the economy.

Some principles of increasing fuel prices are:

- Fuel tax revenues should be used to improve transportation in general, rather than just roads, so that travelers have more fuel efficient accessibility options:

- Revenues generated by the new tax should be returned to individuals and business through reduction in other taxes. That is, taxes should shift from “goods” to “bads”:

- Tax shift should be gradual and predictable, e.g. 10% annually, so consumers and business can take higher energy costs into account when making long-term decisions, such as vehicle purchases and building locations;

- Tax reductions and rebates should be structured to favour lower-income workers and other disadvantaged groups;

- Taxes should be applied to the full category of harmful goods, with minimum exemption, in order to make the tax credible;

- Crucial is an open and appropriate communication policy to let the public understand the underlying principles and reasoning for such policies[1].

Fuel Economy Standards

In addition to price signals, a main instrument to force production of fuel-efficient cars is fuel efficiency of fuel economy standards for car producers. This policy mechanism usually specifies, through a regulatory or political process, the average per-kilometre fuel consumption of new vehicles sold in a given year. Fuel-economy standards are intended to induce innovation in vehicle technologies to curb or reduce oil consumption. Fuel-efficiency standards are meanwhile the most effective climate policy tool in the USA, while the understated fuel taxes are not supporting shifts towards more sustainable transport modes. As car drivers often do not consider fuel consumption when they purchase automobiles, obligatory standards address a crucial market failure. As a disadvantage, they do not influence driving behaviour, and might even induce additional driving (the so-called rebound effect) when no price signals are in place. Government can also act directly by taking their own measures. For example, they can incentivise public transit in their own ranks by providing mobility lump sums for government employees, instead of car benefits. This sets an example for all citizens and can also help capital cities such as Bangkok or Beijing in their drive towards sustainable transport systems. Governments can also choose to purchase highly fuel-efficient duty vehicles[1].

Urban Transport Policies or Programmes

A third key measure is enabling local and urban authorities to advance low-carbon transportation. This is especially important when it comes to investments in low-carbon infrastructure. The major challenge that faces urban policy-makers is to finance a sustainable urban transport system and ensure sustainable funding in the long-term. By providing the necessary financial resources for investment and institutional building, the capacity to raise and manage funding at the local level can be build up and the fragmentation of responsibilities amongst the relevant (transport) authorities can be defeated.

Under this principle national transportation funds can be dedicated at a much larger scale to public transport, bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. A sustainable urban transport policy or program systematically supports cities to invest in low carbon transport systems. Funding is usually related to some conditions, e.g. earmarked for specific measures or the preparation of a comprehensive integrated transport plan[1].

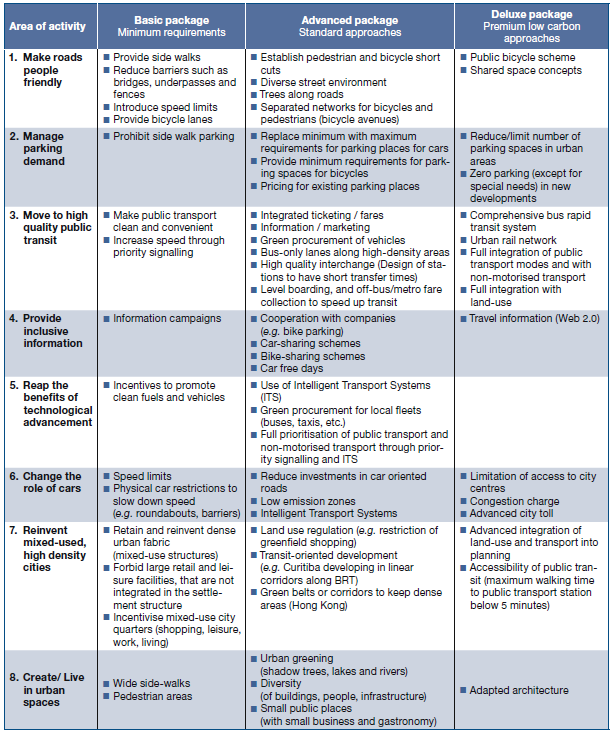

The Low-carbon City

If the current development continues towards car-dependency and concrete miles maximisation, GHG emissions will be fixed for half a century or longer. However, if an alternative low-carbon development gains traction, a fundamental lower emission trajectory can be achieved. As a basic principle on city level, urban development planners should aim at achieving density: the aim must be to retain or achieve medium to high urban density profiles. This is a precondition for efficient and convenient accessibility by walking and cycling, and for making public transport profitable.

In the following three transport-related packages are presented that are linked to the stage of development of a city (basic – advances – deluxe). Each of these packages includes elements in eight different areas of activity. Ideally, policies shall cover each of the eight areas as managing demand requires an approach that optimises different parameters of the transport systems. Thereby, it follows a “Push and Pull Approach”. It is fundamental that a set of measures simultaneously:

- Pushes transport users out of the car or gives incentives to prospective users not to buy a car and, at the same time

- Pulls them to the low carbon modes public and non-motorised transport.

Promoting environmentally friendly modes can increase the attractiveness of a city considerably, and attract both companies and well-qualified employees. Rail modes are rapid and comfortable but less flexible. Buses and mini-buses add local flexibility to the overall system and have the advantage of more speed and comfort, which makes them more competitive to cars. While many Asian cities from Manila to Urumqi invest heavily in highways and motorised transport, the high density of these cities makes them ideal candidates to build an efficient, economically lucrative public transport system from which environment and society can profit.

Road space in most cases cannot be extended in cities, and it makes also no sense, since induces traffic will quickly full up additional space. Therefore the decision is vital on how to best use existing road space. In some advanced cities road space in some inner city streets is only given to Mass Transit, cycling and walking[1].

How can a global deal support low-carbon transportation?

In December, 2009 more than 180 heads of state met in Copenhagen in order to negotiate a new climate change agreement. Even if no final agreement has been achieved, Copenhagen is a step towards realizing the principles of the so called Bali Action Plan. In 2007, the climate talks in Bali outlined the basic elements of a new treaty. This includes that developing countries start to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and fight climate change. In return industrialised countries support developing countries in achieving a low-carbon development path. While OECD countries commit to strict and ambitious emission reduction targets, the developing world would contribute to the prevention of a dangerous climate change through mitigation actions. This includes implementing sustainable transport policies. In Copenhagen, industrialised countries committed to provide support in terms of capacity building, technology and finance. Just after the conference in Copenhagen, 36 developing countries submitted so called “Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions” (NAMAs). These NAMAs are now listed in Annex II to the Copenhagen Accord. Twenty-five of the 36 submissions have made explicit reference to the transport sector, indicating widespread recognition of the role of the sector in the climate change mitigation. They also mirror the wider paradigm shift being pursued in the sector, namely to avoid unnecessary journeys, shift travel activity to low carbon modes, and improve the energy efficiency of each mode. NAMA actions proposed have, for example, ranged from land-use planning to increasing the energy efficiency of vehicles and fuels and research into the impacts of different strategies.

For reductions, not a single policy but a set of integrated measures is required to achieve a decarbonisation of transportation. Low carbon transport strategies are well suited and related to a sustainable transport policy and worth being carefully checked and considered by transport ministries in the coming years[1].

Further Information

Further and more detailed information can be found on the homepage of the Sustainable Urban Transport Project. The Sustainable Urban Transport Project aims to help developing world cities achieve their sustainable transport goals, through the dissemination of information about international experience, policy advice, training and capacity building.