Knowledge fuels change - Support energypedia!

For over 10 years, energypedia has been connecting energy experts around the world — helping them share knowledge, learn from each other, and accelerate the global energy transition.

Today, we ask for your support to keep this platform free and accessible to all.

Even a small contribution makes a big difference! If just 10–20% of our 60,000+ monthly visitors donated the equivalent of a cup of coffee — €5 — Energypedia would be fully funded for a whole year.

Is the knowledge you’ve gained through Energypedia this year worth €5 or more?

Your donation keeps the platform running, helps us create new knowledge products, and contributes directly to achieving SDG 7.

Thank you for your support, your donation, big or small, truly matters!

The Economics of Renewable Energy

► Back to Financing & Funding Portal

Overview

In order to assess how private investment in renewables can be increased, it is necessary to understand the economics of renewable energy.

Rationale for Renewables

Worldwide more energy is required to enable economic development. Fossil fuels are a finite resource that contribute to climate change and cause other problems like smog, extended supply lines and vulnerable power grids. Utilizing renewables would help to avoid these problems, create new job opportunities and reduce the drain on hard currency for poorer countries. Because conventional fuels have received long-term subsidies in the past, it is vital that governments support the development of renewables in the form of financial incentives that can create a level playing field [1].

According to REN-21’s Renewables Global Futures Report 2013, the future of renewable energy is uncertain as finance remains a key challenge. The future of the renewables industry depends on finance, risk-return profiles, business models, investment lifetimes and a host of other economic, policy and social factors. Many new sources of finance are possible such as insurance funds, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds along with new mechanisms for financial risk mitigation. Many new business models are also possible for local energy services, utility services, transport, community and cooperative ownership, and rural energy services [2].

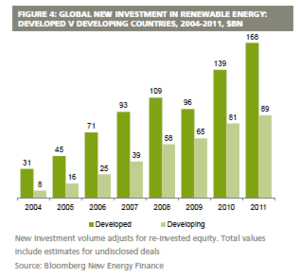

In 2011, the global investment in renewable power and fuels increased by 17% to a new record of $257 billion dollars. Significantly, developing economies made up 35% of this total investment [3].

Despite these trends, renewable energy technologies (RETs) continue to face a number of barriers [4]. (See Barriers for Renewable Energy Financing)

When assessing decisions to support RET’s, policy-makers need answers to the following questions:

- Are renewables more expensive that fossil fuels?

- Can renewables be made available on a scale large enough to replace fossil fuels?

Costs of Renewable Energy

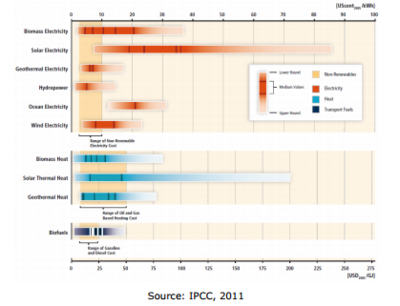

Generally the economics of renewable energy are not competitive, as production costs per unit of energy are usually higher than those for fossil fuels as depicted in the figure below, which shows the relative costs for renewable energy technologies compared with each other, and with non-renewable energy[5].

As shown in the figure, while non-renewable costs are found in the range of US$0.3–US$0.10/KwH (kilowatt hour), most renewables are more expensive and have a far greater cost range. This indicates the relative maturity of technologies and also the key significant cost difference of renewable energy production (which is dependent on factors such as wind speed and degrees of solar intensity.)

Scale is also an important issue. This is due to the fact that fossil-fuel technologies have been developed, improved and manufactured on an increasing scale for a century. This is not yet the case for renewables[5].

These factors suggest that there is scope to reduce the varying production costs of renewables.

- The most expensive form of renewable energy is ocean/tidal electricity, which, even at the bottom of the potential cost range, remains uncompetitive with fossil fuels.

- Onshore and offshore wind and large solar photovoltaic (PV) plants today require policy support in order to bridge the gap bewteen geration costs and the markert prices of elecrticty. This is expected to change in the near future as reported bay the International Energy Agency's Renewable Energy Technology Deployment Group.

- The next is solar power, which at its cheapest is potentially competitive with fossil fuels. However, its midrange costs are well above fossil fuels. This wide range reflects the cost implications of different technologies. For example, large-scale Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) techniques employed in a desert environment could produce electricity at a far lower cost than small solar panels fitted to residential properties.

- Wind power can be cheaper, but remains more expensive than fossil fuels in most instances. This range reflects differing scales of energy generation, but also the different cost structures of onshore and offshore wind.

- Biomass, geothermal and hydropower in particular are already competitive with fossil fuels in some circumstances [5].

New onshore and offshore wind and large solar photovoltaic (PV) plants still require policy support to bridge the gap between generation costs and market prices of electricity. But this may change in the near future, finds a new reportfrom the International Energy Agency’s Renewable Energy Technology Deployment group. Technology and market dynamics are driving down the costs of renewable power generation while increasing the costs involved in non-renewable generation, the report found. Before long, it said, best-in-class onshore wind and large-scale PV plants should be able to offer attractive business cases to investors in regions with a high proportion of thermal generation without resorting to incentives.

The report, which focused on Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Norway, Sweden and Spain, noted that policies and regulations can significantly affect the business cases of both renewable and non-renewable power sources. Although the high cost of generation for new renewable energy technologies means policy support is currently needed, the report noted that generation costs for renewable power are falling, approaching the costs for gas- and coal-fired plants — especially if the hidden subsidies that thermal generation plants may receive are taken out of the equation.

Onshore wind generation is already competitive in the report's focus countries. Large-scale PV’s rate of cost reduction is higher, though, due to technology breakthroughs, the emergence of lower-cost suppliers and component oversupply.

At the same time, the report stated, the cost of gas- and coal-fired plants is increasing because they are being used less — largely due to policy support for renewables, construction delays, higher financing rates, and the increasing cost of fuel in some European countries and Japan. Most crucial is the higher capital costs involved in some new-build thermal plants due to emission reduction systems, the report argued. “The future competitiveness of thermal generation is going to be positively or negatively influenced by the shape and provisions of future policies for control of emissions,” it said.

One unsurprising conclusion is that there is no unique cost of renewable or non-renewable power generation. Cost ranges associated with any power generation technology are relatively large and highly dependent on the regulatory and market contexts, the report said. It pointed to best-in-class plants — those with high utilisation rates, low capital costs, and low rates of financing — rather than to any particular technology as having generation costs up to 50 percent lower than average plants. It singled out the case of large-scale PV, where comparing plants built several years apart and based on different technologies showed big differences in cost. Policies in some regions also significantly affect generation costs by offering a variety of reward mechanisms, such as R&D grants, assumption by the TSO of the cost of connecting to the grid, tax breaks and reduction of administrative burdens.

Both new renewable and new non-renewable power plants find it difficult to compete in regions where the market prices of electricity remain low, said the report. This is driven in part by excess capacity, and also by an installed base that includes depreciated plants.

In general, the costs of both new renewable power plants and new non-renewable generation are higher than the market price of electricity, because of which the report stressed the necessity of maintaining current incentives in order to provide business cases that will interest investors. However, it noted that when incentives do not exist or are not appropriately defined, “the business case of new generation does not hold.”

Costs of Fossil Fuels

Costs relative to fossil fuels are also important particularly because:

1. Fossil-fuel energy does not reflect its full social costs.

- Climate change has been described as the "biggest market failure in history" (Stern Review, 2006) because the environmental costs associated with carbon emissions are not included in market prices.

- Furthermore, fossil fuels are subsidized for about US$300 billion per year. Removing theses subsidies and incorporating externalities into fossil fuel costs would dramatically change relative costs[5].

2. It is more expensive to deliver non-renewable energy in some places than others.

- For example, rural communities in developing countries are often not connected to the grid, resulting in "off-grid" energy production - particularly solar power - being more competitive[5].

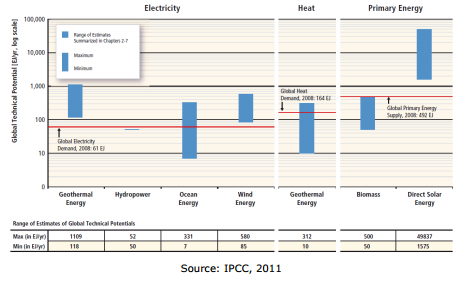

3. There is no shortage of renewable energy potential at the global level (See figure below).

- In terms of primary energy, it is already technically possible to generate many multiples of global energy supply using solar energy. There is also an abundant supply of wind or geothermal power to meet all of today’s global electricity demand[5].

It is significant that much of the global solar power is concentrated in developing countries, although other areas also have a high potential.

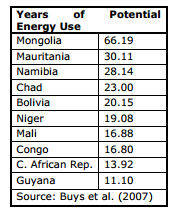

The table below shows the top 10 countries globally in terms of renewable energy potential relative to energy use.They are all developing countries, which reflects their relatively low energy use at present, but also the relative abundance of solar, wind, hydro and geothermal energy [5].

Increasing the Use of Renewable Energy

There is significant scope to increase the use of renewables especially in developing countries. However, this potential is not limitless. Although it can be expected that the costs of renewables will continue to fall relative to fossil fuels, (especially in countries with high renewable energy potential), fossil fuels will probably retain a cost advantage[5].

Expansion of Renewable Energy Use:

- The basic economics of renewable energy need to be artificially altered, either by increasing the cost of fossil fuel-based energy (e.g. through taxes or equivalent mechanisms), or by reducing the costs of renewable energy (e.g. subsidies), or by boosting the returns to renewable energies (e.g. through paying a premium for this form of energy) [5].

- Developing countries should not necessarily be required to meet these costs. This is particularly so where the development of renewable energy capacity may place countries at a competitive disadvantage and/or these countries bear no responsibility for climate change. The costs should be met by countries that do bear these responsibilities. This case is even stronger while developed countries are subsidizing fossil-fuel energy[5].

Further Information

- Assessing the Economic Viability of Business Ideas for Productive Use

- Economic and Financial Impacts of Grid Interconnections

- Economic Viability of a Biogas Plant

- Economic Analyses of Wind Energy Projects

- Macro-economic evaluation of Biogas Plants

- Socio-economic and Environmental Impacts of MHP

- Subsidies

References

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), 2004. CEO briefing - Renewable Energy, Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI).

- ↑ Appleyard, D., March 2013. The Future of Renewables: Economic, Policy and Social Impications - Renewable Energy World International. Available at: http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2013/03/from-the-editor20

- ↑ Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance, 2012. Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2012, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Frankfurt School UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance.

- ↑ These barriers can be financial and economically such as, higher upfront costs, political and regulatory (generally policies do not favour renewable technologies), environmental and social (e.g. planning objections), technical (e.g. intermittent nature of renewable technologies), or related to the scale of the projects, mainly higher transaction costs. To create a level playing field for renewable technologies, all the barriers mentioned above need to be addressed, but the crucial starting point is a supportive and stable policy and regulatory framework. This will encourage greater investment on the part of financial institutions. (United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), 2004)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Griffith-Jones, S., Ocampo, J. A. & Spratt, S., 2011. Financing Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Mechanisms and Responsibilities. Available at: http://erd-report.eu/erd/report_2011/documents/dev-11-001-11researchpapers_griffith-jones-ocampo-spratt.pdf