Urban Logistics

The Way Forward: Options for Dealing with Urban Logistics

Any policy measure in the field of urban freight management requires a solid foundation for it to be effective. This foundation consists of good administration practice on the side of the local authorities and regional or state governments, a sound legislative framework, clearly assigned institutional roles and a general attitude of civic compliance amongst the players involved in the urban transport business (transport operators, drivers, shippers and receivers).

Basic requirements for an efficient management of urban freight traffic include[1]:

- Coherent policies on the transportation sector, on business licensing and on urban development;

- Clearly assigned institutional responsibilities;

- An adequate legal and organizational framework;

- Functioning road taxation and vehicle licensing mechanisms;

- A sense of civic compliance amongst the parties involved.

Traffic Management

The term “Traffic Management” refers to all measures which can be taken by local authorities to manage the flow of vehicles and the available traffic space by means of regulations, signage, road marking, road pricing, control and enforcement measures. This is a differentiation over the term “Traffic engineering”, which refers to the planning and construction of road infrastructure.

A thorough assessment of a city’score freight traffic problems stands at the beginning of all traffic management on a community level, which is often handled by the Traffic Department or a comparable authority. The first priority is to handle bottleneck situations, where freight transport contributes significantly to congestion. Some of the basic instruments that can help organise city freight traffic efficiently are[1]:

- Signage;

- Light signalling;

- Road marking;

- Implementation of one-way schemes and circular routes;

- Installation of physical barriers;

- Issue of access permits;

- Road pricing and transport demand management.

Enforcement

An effective enforcement is the pivotal element in the management of urban traffic space. Where enforcement cannot be assured, further traffic management measures are likely to fail. With respect to urban freight transport, some of the core enforcement functions are[1]:

- Prevent second row (double) parking;

- Enforce “no loading” and “no waiting” restrictions;

- Penalise overload and oversize of vehicles;

- Penalise unauthorised entry and failure to pay congestion charges (mostly camera enforcement);

- Prevent shoppers to park in designated loading bays.

Avoiding Through-Traffic

For through-traffic, the city itself is not the destination. Instead it only passes through the city area on its way to other destinations, causing additional congestion. This is often the case for traffic destined to ports or airports, going through the city centre or sub centres instead of being routed onto ring roads and around the worst points of congestion. The first condition for avoiding unnecessary through traffic is the availability of alternative routes. Through-traffic avoidance is therefore primarily a road infrastructure or mode shift issue.

However, in many cases detrimental through traffic flows for goods transport occur in spite of alternative routes having been put in operation. Truck drivers often insist to use a more direct or apparently more attractive route, although reserved for local traffic only. Local governments can use a wide range of measures to respond to this phenomenon. This includes the following options[1]:

- Signed street closures for all commercial vehicles;

- Signed access restriction for commercial through traffic with intensive enforcement;

- Physical street closures for commercial vehicles (height restricting gates or narrowly spaced bollards);

- Road design, giving priority to the alternative route and making it the more convenient route rather than the one through the city;

- Placement of tollgates for any commercial traffic, including through traffic and local traffic, at critical points of convergence (e.g. bridges or tunnels), provided that there are no viable avoidance routes.

Introducing Access Restrictions

A fairly easy measure to implement is the imposing of access restriction to certain urban areas. This can be done in order to control congestion and air pollution or to protect local commerce, tourism, and residents.

Alternatively, physical restrictions such as automatic booms, height restricting bars, retractable bollards, etc. can be used.

In most cases, the purpose of the restrictive measures is not to close a certain area for motorized vehicles completely, but to restrict access for vehicles based on selective characteristics like delivery times, vehicle size or weight. Typically, commercial goods traffic to inner-city centres is allowed in certain time windows only. This measure is commonly referred to as a “truck ban”. Some cities have found a practical compromise to increase logistics performance: They restrict large vehicle during the daytime and allow them into the city area at night[1].

Selective Road Pricing and Permits

The city administration can choose the following characteristics as requirements for access to an inner city area[1]:

- Low emission engine technologies, limitation of CO2, NOX and particle emissions;

- Roadworthy certificate;

- Easy unloading features, such as side doors, tail-lift, etc.

- Restrictions to vehicle maximum and/or minimum size.

Access restrictions are a pragmatic way to achieve a certain level of efficiency in city freight operation. However, these measures should be seen as a basis for follow-up action in the inner structure of the logistics system.

Avoidance of Orientation Traffic

Orientation traffic is usually caused by drivers who are unfamiliar with the local situation. A simple measure to help drivers to find their destination is the maintenance of street name plates and the provision of clear and visible direction signs and parking provisions. If considering the introduction of similar concepts in developing cities, it is essential to involve truck drivers at an early stage of the planning. It should be kept in mind that in some societies people are not familiar with reading and understanding maps and directions[1].

General Traffic Space Management

In many metropolitan areas, the extreme diversity of transport modes, ranging from pedestrians, via animal-hauled cart, two-wheel-, three-wheel-transport, cars, vans, light trucks to sometimes overloaded heavy trucks, presents a problem in itself. Whenever traffic space is too scarce for space separation schemes, time sharing concepts are a good way to improve the road network and parking capacity. Wherever no mode separation can be achieved at all, speed restrictions may at least alleviate the friction between vehicle classes and reduce the accident risk. With stringent enforcement, high powered vehicles can thereby be forced to adjust to the speeds of surrounding two and three-wheeler traffic[1].

Traffic Engineering

The term “Traffic Engineering” refers to the planning, construction, maintenance, operation and upgrading of basic road infrastructure.

Provision of Adequate Loading Zones

The required space for one commercial vehicle has a width of 2 m and a length of 10 m to 18 m, depending on the predominant vehicle sizes. It should include a handling area of 2 m at the position of the tailgate, with level surface and access to the adjacent sidewalk system.

Unloading Goods: Organization of the “Last Yard”

Delivery routes into the inner-city centres are often referred to as “the last mile”. Likewise, the organisation of the goods vehicle parking next to a shop and the unloading operation could be referred to as the “last yard”. As a general rule, it can be said that loading spaces are more difficult to implement and more difficult to enforce, the closer they are to the receiver’s shop or business. A measure to solve this problem is the provision for a non-motorised form of short distance transport between truck and shop entrance. This practice will be referred to as “vicinity unloading”, meaning that the goods vehicles park in a designated loading zone nearby one or several drop-off points. The goods will then be carried or carted across a short city distance to the handover point[1].

Operating a larger unloading area poses less compliance and enforcement problems than having dispersed individual loading bays. Depending on the size and conditions, it could be possible to provide physical access control, guarding, provision of sack-barrows or handstackers and even short-term storage, if needed.

Urban Planning

Even though traffic management and traffic engineering solutions can provide a certain alleviation of the problems currently posed by growing city freight traffic, the long term challenges are best met by a far-sighted policy on urban development, land use and spatial planning.

Involve the Local Business Community

In most cases it is necessary to require the local business community to contribute to the facilitation of smooth urban logistics and traffic flow. This can be achieved via adequate planning regulations by municipal authorities. In zones with extremely constrained space, multi-purpose buildings could be envisaged, with the basement our ground floor serving for parking and loading, the others for retail and offices.

Promote Intermodality on a Metropolitan Level

If suitable pieces of land are available alongside an inland waterway, sea port or rail line to establish distribution logistics centres, this may be an efficient way of reducing congestion caused both by through-traffic as well as inner city distribution operations. In an intermodal situation, i.e. with goods arriving by ship or by rails, it is usually much easier to make delivery in consolidated loads viable than for pure road transport operations.

Land-banking for Future Infrastructure Requirements

In case where it is not yet necessary to establish urban freight consolidation centres, it may be reasonable to make provision for future implementation. Such provision will have to be integrated in the spatial planning process, e.g. via Landbanking. This is a practice, whereby a certain amount of public space is reserved for special future requirements when a certain city area is developed, or when an infrastructure project is implemented.

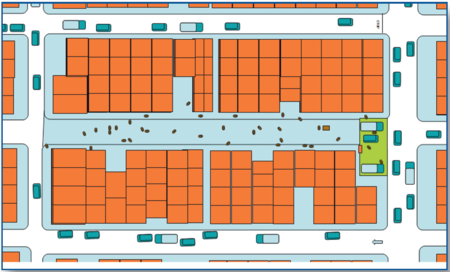

Spaces for the Installation of Urban Logistics Distribution Centers

It is likely that at some point in the future city delivery conditions will become so restrained, that operators are either voluntarily going to use load consolidation schemes, or that it will become necessary to enforce this practice by public intervention. It is of utmost importance to plan such centres in appropriate locations. In order to prevent what is called “logistics sprawl”, with negative effects on overall kilometrage generation, the logistics establishments must be placed in immediate vicinity of their respective catchment areas. This means that the distance between the consolidation center and the inner-city delivery area must be kept as short as possible[1].

National Development Policy and Legislation

Legal Framework

Many of the base conditions for a safe and efficient urban freight transport operation are determined here. For example, National Highway Codes or Road Transport Codes, regulate road vehicle dimensions, admissible weights and technology requirements. Vehicle registration fees, taxation, driver training and licensing, as well as the vehicle inspection regime are usually also determined on a national level[1].

Environmental Policy

Introduction of Fixed or Progressive Emission Standards

- Introduce minimum emission standards for all road vehicles being imported or for new registration. These standards can be tightened over time, in line with the modernization of the national fleet.

- Introduce regular vehicle inspection or extend the programme of the existing inspection in order to ensure testing and enforcement of the legal emission levels.

- Introduce minimum standards for the existing fleet, thereby forcing low performers out of operation.

Push and Pull Measures

- Apply selective road taxation, giving preference to low emission vehicles (i.e. lower tax burden for more eco-efficient vehicles);

- Tighten up the vehicle inspection regime for vehicles in high emission classes.

Deployment Restrictions

- Introduce stricter standards for urban operation as opposed to the national/provincial legislation, e.g. through access restrictions on high emission vehicles for the entire urban area or for specific environmental zones

- Impose time-window related restrictions;

- Sell access permits at selective prices, according to the emission standard fulfilled.

Tightened Vehicle Inspection Regime

Introduce adequate vehicle inspection intervals with emission testing;

- Introduce mobile roadside truck inspections with emission testing[1].

Summary

The relevance of urban freight traffic is increasingly recognized in developed and developing cities alike. Efforts to reduce its negative impacts are driven by a wide range of motivations, which very much depend on the local context. There is a need for co-operation between public and private actors to improve the efficiency of urban freight operations and, as a consequence, to mitigate its negative impacts. As goods transport in urban areas is mostly in the hands of a multitude of private companies, ranging from micro businesses to global players, the importance of dialogue between all stakeholders cannot be underestimated. There is no single master plan, and no predefined set of necessary measures to reduce negative impacts of urban freight traffic. Policy-makers will have to choose actions suitable to solve to most urgent problems, and may have to adapt them to the specific local context. However, there are certain aims a municipal authority can strive to achieve. They characterize a situation in which urban logistics can be managed in an efficient and sustainable manner. Whatever the approach may be: cities and metropolitan areas have to develop and implement a viable strategy for the optimisation of the urban freight system. The environmental sustainability, economic development and overall quality of urban living depend on it[1].

Further Information

- Further and more detailed information can be found on the homepage of the Sustainable Urban Transport Project. The Sustainable Urban Transport Project aims to help developing world cities achieve their sustainable transport goals, through the dissemination of information about international experience, policy advice, training and capacity building.