Difference between revisions of "Energy Poverty"

***** (***** | *****) |

***** (***** | *****) m |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | = | + | = Overview<br/> = |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | = | + | '''[[File:Children reading.jpg|left|x198px|alt=Children reading.jpg]]Energy poverty '''is a lack of access to [[Access to Modern Energy|modern energy services]]. These services are defined as household access to electricity and clean cooking facilities (e.g. fuels and stoves that do not cause [[Indoor Air Pollution (IAP)|air pollution]] in houses).<ref name="IEA: http://www.iea.org/topics/energypoverty/">IEA: http://www.iea.org/topics/energypoverty/</ref> |

| − | + | Access to energy is a prerequisite of human development. Energy is needed for individual survival, it is important for the provision of social services such as education and health and a critical input into all economic sectors from household production or farming, to industry. The wealth and development status of a nation and its inhabitants is closely correlated to the type and extent of access to energy. The more ready usable energy and the more efficient energy converting technologies are available, the better are the conditions for development of individuals, households, communities, the society and its economy. Thus, improving access to energy is a continuous challenge for governments and development organisations.<ref>energypedia:https://energypedia.info/wiki/Access_to_Modern_Energy#Overview</ref><br/> | |

| − | + | {{#widget:YouTube|id=rmNIvprg1dM|height=300|width=600}} | |

| − | + | = Approaches for Defining Energy Poverty = | |

| − | + | == Definition by Douglas F. Barnes (Energy for Development)<br/> == | |

| − | + | The existence of energy poverty today is quite well accepted around the world. In fact alleviating energy poverty is a goal of many development organizations that deal with energy issues for developing countries. However, when it comes to defining energy poverty these organizations assume the position that many take in appreciating good art--"they know it when they see it." There is much talk about energy poverty but not much action in terms of measuring it. Further analytical work on both definitions and measurement tools is required to underpin delivery and policy formation.<ref>Bazilian et al. 2010. Measuring Energy Access: Supporting a Global Target. http://www.unido.org/index.php?id=1000598</ref> There is a good reason the people avoid defining energy poverty. It just is very thorny to define. There even was a time not too long ago that development specialists refrained from using the term. One can ask several different questions concerning the definition of energy poverty. Is energy poverty the same as income poverty? Is energy poverty based on access to energy services such as cooking, communications or lighting? Or is it based on quantities of energy that people use? These questions have generated several different approaches to measuring energy poverty.<br/> | |

| − | + | <u>There are several different approaches to define energy poverty and they can be classified as follows and are explained below:</u><br/> | |

| − | + | #Minimum amount of physical energy necessary for basic needs such as cooking and lighting; | |

| + | #Type and amount of energy that is used for those at the poverty line; | ||

| + | #Households that spend more than a certain percent of their expenditure on energy; | ||

| + | #The income point below which energy use and or expenditures remains the same, implying this is the bare minimum energy needs. | ||

| − | + | <br/>Each one of these approaches has strengths and weaknesses.<br/> | |

| − | + | #The first way of defining energy poverty has its roots in defining poverty as a minimum amount of food intake necessary to sustain a health life. This is a very common approach often used by international food agencies. Translating this method to energy, there also must be a '''minimum amount of energy''' '''necessary to cook, light and heat someone’s home'''. Although this might be true, pinning down the exact minimum level of energy necessary based on basis needs is very difficult due to the significant country and regional differences in cooking practices and heating requirements. We know the caloric levels that are necessary to sustain a healthy life, but pinning down the minimum energy needs is much more difficult to accomplish.<ref name="barnes">D. Barnes: The Concept of Energy Poverty, http://www.energyfordevelopment.com/2010/06/energy-poverty.html</ref> | |

| + | #The second approach of defining the energy poverty line as the '''energy being used by households below the known expenditure or income poverty line''' is much easier to grasp. The expenditure based poverty line is well defined in most countries, so based on a household energy survey you assess the average fuel use below this level. This is fairly attractive because it is not necessary to actually measure how much energy people are using. However, this method also has the drawback that you are defining energy poverty based on more general critera as opposed on an energy basket of goods and services. This means that such a poverty line would not be based on the energy policies in the country, but rather would reflect general economic and social policies. Tracking energy poverty with this method would be no more than tracking general poverty trends. This method is not so useful for those that might want to tack the impact of energy sector reform.<ref name="barnes">_</ref> | ||

| + | #The third line of thought is that the energy poverty should be based on the '''percentage of income spent on energy'''. It is well established that households that are poor spend a higher percentage of their income on energy than households that are wealthier. Empirical studies including ones I have done indicate that such percentages can range from about 5% or less to close to 20% of cash income or expenditure. It seems that when energy is above 10% of income, then conceivably it will begin to have an impact on general household welfare. The idea is that when households are forced to spend as much as 10% of cash income on energy they are being deprived of other basic goods and services necessary to sustain life. The drawback to this approach is that 10% is a rather arbitrary figure. So it suffers to a certain extent from the same problems as the methods based on physical measures of energy.<ref name="barnes">_</ref> | ||

| + | #The last method is based on the '''level of energy demand as it relates to household income'''. The sweet spot for poverty specialists is the level of income at which the use of energy or the level of energy expenditures does not vary significantly with income. The converse of this is that after a certain level of income people begin to consume more and more energy. For poor people this means that even if their income increases, their use of energy does not because they are at the bare minimum amount necessary to sustain daily life as illustrated in the figure. Unfortunately, this approach is quite data intensive and requires the analysis of household surveys that have good energy questions. The attractiveness is that this definition of energy poverty is based on how people actually consume energy based on local resource conditions, energy prices and policies.<ref name="barnes">_</ref> | ||

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | = Exemplary Definitions of Energy Poverty = | |

| − | + | == Definition from Practical Action == | |

| − | <br> | + | <u>A person is in ‘energy poverty’ if they do not have access to at least:</u><br/> |

| − | + | (a) the equivalent of 35 kg LPG for cooking per capita per year from liquid and/or gas fuels or from improved supply of solid fuel sources and improved (efficient and clean) cook stoves<br/> | |

| − | <br> | + | '''AND'''<br/> |

| − | + | (b) 120kWh electricity per capita per year for lighting, access to most basic services (drinking water, communication, improved health services, education improved services and others) plus some added value to local production | |

| − | <br> | + | An improved energy source for cooking is one which requires less than 4 hours person per week per household to collect fuel, meets the recommendations [http://www.who.int/en/ WHO] for air quality (maximum concentration of CO of 30mg/M3 for 24 hours periods and less than 10mg/ M3 for periods 8 hours of exposure), and the overall conversion efficiency in higher than 25%. <ref>Practical Action: Energy Poverty: Estimating the Level of Energy Poverty in Sri Lanka, http://practicalaction.org/docs/region_south_asia/energy-poverty-in-sri-lanka-2008.pdf</ref><br/> |

| − | + | ► [http://practicalaction.org/ Practical Action] | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | == Development of an Energy Poverty Line == | |

| − | + | ► Download: [http://d.repec.org/n?u=RePEc:wbk:wbrwps:5332&r=ene Energy access, efficiency, and poverty: how many households are energy poor in Bangladesh?] by: Barnes, Douglas F., Khandker, Shahidur R., Samad, Hussain A. | |

| − | <br> | + | <br/>Abstract: Access to energy, especially modern sources, is a key to any development initiative. Based on cross-section data from a 2004 survey of some 2,300 households in rural Bangladesh, this paper studies the welfare impacts of household energy use, including that of modern energy, and estimates the household minimum energy requirement that could be used as a basis for an energy poverty line. The paper finds that although the use of both traditional (biomass energy burned in conventional stoves) and modern(electricity and kerosene) sources improves household consumption and income, the return on modern sources is 20 to 25 times higher than that on traditional sources. In addition, after comparing alternate measures of the energy poverty line, the paper finds that some 58 percent of rural households in Bangladesh are energy poor, compared with 45 percent that are income poor. The findings suggest that growth in electrification and adoption of efficient cooking stoves for biomass use can lower energy poverty in a climate-friendly way by reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Reducing energy poverty helps reduce income poverty as well. |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | + | <br/> | |

| − | < | + | <br/> |

| − | + | == Energy Poverty in the World Energy Outlook 2015<br/> == | |

| − | + | <u>The Energy Outlook 2015 assesses two indicators of energy poverty at HH level:</u><br/> | |

| − | [[Category:Impacts]] [[Category: | + | *Lack of access to electricity<br/> |

| + | *Reliance on the traditional use of biomass for cooking<br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/><u>Greatest challenge: SSAfrica</u><br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *35% electrification rate<br/> | ||

| + | *2011: 696 mio relying on traditional biomass<br/><br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ► Download: [http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weowebsite/2015/WEO2015_Factsheets.pdf World Energy Outlook 2015 Factsheet]<br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ► Download: [http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weo2010.pdf World Energy Outlook 2010 (IEA)]<br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ► Download Presentation (Verena Brinkmann): [[:File:IEA UNDP UNIDO Energy Poverty WEO 2010.pptx|IEA UNDP UNIDO Energy Poverty WEO 2010]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Measuring Energy Poverty = | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI) == | ||

| + | |||

| + | <u>Abstract:</u> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The provision of modern energy services is recognised as a critical foundation for sustainable development, and is central to the everyday lives of people. Effective policies to dramatically expand modern energy access need to be grounded in a robust information-base. Metrics that can be used for comparative purposes and to track progress towards targets therefore represent an essential support tool. This paper reviews the relevant literature, and discusses the adequacy and applicability of existing instruments to measure energy poverty. Drawing on those insights, it proposes a new composite index to measure energy poverty. Both the associated methodology and initial results for several African countries are discussed. Whereas most existing indicators and composite indices focus on assessing the access to energy, or the degree of development related to energy, our new index – the '''Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI)''' – focuses on the deprivation of access to modern energy services. It captures both the incidence and intensity of energy poverty, and provides a new tool to support policymaking. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/>► Download: [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032111003972 Measuring energy poverty: Focusing on what matters] (science direct), [http://www.un-energy.org/measuring-energy-access Supporting Sustainable Development through Knowledge (UN)] by: Patrick Nussbaumer, Morgan Bazilian, Vijay Modi, and Kandeh K. Yumkella | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Further Information<br/> = | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Energy Access Figures|Energy Access Figures]] on energypedia | ||

| + | *[[Figures on Energy Poverty|Figures on Energy Poverty]] on energypedia | ||

| + | *[[Access to Modern Energy|Access to Modern Energy]] on energypedia<br/> | ||

| + | *[http://www.se4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/GTF-2105-Full-Report.pdf Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All) Global Tracking Framwork Report 2015]<br/> | ||

| + | *[http://www.iea.org/topics/energypoverty/ IEA Energy Poverty]<br/> | ||

| + | *[http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/energy-poverty The Guardian - Energy Poverty]<br/>News and comment on energy and fuel poverty in the developing world | ||

| + | *[http://www.se4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Special_Excerpt_of_WEO_2010.pdf OECD/IEA (2010): Energy Poverty. How to make modern energy access universal?]<br/> | ||

| + | *[http://www.africapowerltd.com/energy-poverty-and-access-to-power/ http://www.africapowerltd.com/energy-poverty-and-access-to-power/] | ||

| + | *"Energy poverty, or the lack of access to electricity and other basic energy services, affects nearly two-thirds of Sub-Saharan Africa. As the region's population continues to increase, so will the need to build a new energy system to grow with it, says Rose M. Mutiso. In a bold talk, she discusses how solutions like off-grid solar, wind farms and hydroelectric and geothermal power could create a high-energy future for Africa -- providing reliable electricity, creating jobs and raising incomes." Listen to her podcast (<span class="f-w:700">TEDSummit 2019 </span><span>| July 2019</span>): https://www.ted.com/talks/rose_m_mutiso_how_to_bring_affordable_sustainable_electricity_to_africa?rss=172BB350-0368 | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | = References = | ||

| + | |||

| + | <references /><br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Impacts]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Energy_Access]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:58, 28 October 2019

Overview

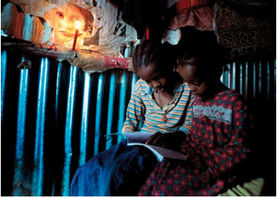

Energy poverty is a lack of access to modern energy services. These services are defined as household access to electricity and clean cooking facilities (e.g. fuels and stoves that do not cause air pollution in houses).[1]

Access to energy is a prerequisite of human development. Energy is needed for individual survival, it is important for the provision of social services such as education and health and a critical input into all economic sectors from household production or farming, to industry. The wealth and development status of a nation and its inhabitants is closely correlated to the type and extent of access to energy. The more ready usable energy and the more efficient energy converting technologies are available, the better are the conditions for development of individuals, households, communities, the society and its economy. Thus, improving access to energy is a continuous challenge for governments and development organisations.[2]

Approaches for Defining Energy Poverty

Definition by Douglas F. Barnes (Energy for Development)

The existence of energy poverty today is quite well accepted around the world. In fact alleviating energy poverty is a goal of many development organizations that deal with energy issues for developing countries. However, when it comes to defining energy poverty these organizations assume the position that many take in appreciating good art--"they know it when they see it." There is much talk about energy poverty but not much action in terms of measuring it. Further analytical work on both definitions and measurement tools is required to underpin delivery and policy formation.[3] There is a good reason the people avoid defining energy poverty. It just is very thorny to define. There even was a time not too long ago that development specialists refrained from using the term. One can ask several different questions concerning the definition of energy poverty. Is energy poverty the same as income poverty? Is energy poverty based on access to energy services such as cooking, communications or lighting? Or is it based on quantities of energy that people use? These questions have generated several different approaches to measuring energy poverty.

There are several different approaches to define energy poverty and they can be classified as follows and are explained below:

- Minimum amount of physical energy necessary for basic needs such as cooking and lighting;

- Type and amount of energy that is used for those at the poverty line;

- Households that spend more than a certain percent of their expenditure on energy;

- The income point below which energy use and or expenditures remains the same, implying this is the bare minimum energy needs.

Each one of these approaches has strengths and weaknesses.

- The first way of defining energy poverty has its roots in defining poverty as a minimum amount of food intake necessary to sustain a health life. This is a very common approach often used by international food agencies. Translating this method to energy, there also must be a minimum amount of energy necessary to cook, light and heat someone’s home. Although this might be true, pinning down the exact minimum level of energy necessary based on basis needs is very difficult due to the significant country and regional differences in cooking practices and heating requirements. We know the caloric levels that are necessary to sustain a healthy life, but pinning down the minimum energy needs is much more difficult to accomplish.[4]

- The second approach of defining the energy poverty line as the energy being used by households below the known expenditure or income poverty line is much easier to grasp. The expenditure based poverty line is well defined in most countries, so based on a household energy survey you assess the average fuel use below this level. This is fairly attractive because it is not necessary to actually measure how much energy people are using. However, this method also has the drawback that you are defining energy poverty based on more general critera as opposed on an energy basket of goods and services. This means that such a poverty line would not be based on the energy policies in the country, but rather would reflect general economic and social policies. Tracking energy poverty with this method would be no more than tracking general poverty trends. This method is not so useful for those that might want to tack the impact of energy sector reform.[4]

- The third line of thought is that the energy poverty should be based on the percentage of income spent on energy. It is well established that households that are poor spend a higher percentage of their income on energy than households that are wealthier. Empirical studies including ones I have done indicate that such percentages can range from about 5% or less to close to 20% of cash income or expenditure. It seems that when energy is above 10% of income, then conceivably it will begin to have an impact on general household welfare. The idea is that when households are forced to spend as much as 10% of cash income on energy they are being deprived of other basic goods and services necessary to sustain life. The drawback to this approach is that 10% is a rather arbitrary figure. So it suffers to a certain extent from the same problems as the methods based on physical measures of energy.[4]

- The last method is based on the level of energy demand as it relates to household income. The sweet spot for poverty specialists is the level of income at which the use of energy or the level of energy expenditures does not vary significantly with income. The converse of this is that after a certain level of income people begin to consume more and more energy. For poor people this means that even if their income increases, their use of energy does not because they are at the bare minimum amount necessary to sustain daily life as illustrated in the figure. Unfortunately, this approach is quite data intensive and requires the analysis of household surveys that have good energy questions. The attractiveness is that this definition of energy poverty is based on how people actually consume energy based on local resource conditions, energy prices and policies.[4]

Exemplary Definitions of Energy Poverty

Definition from Practical Action

A person is in ‘energy poverty’ if they do not have access to at least:

(a) the equivalent of 35 kg LPG for cooking per capita per year from liquid and/or gas fuels or from improved supply of solid fuel sources and improved (efficient and clean) cook stoves

AND

(b) 120kWh electricity per capita per year for lighting, access to most basic services (drinking water, communication, improved health services, education improved services and others) plus some added value to local production

An improved energy source for cooking is one which requires less than 4 hours person per week per household to collect fuel, meets the recommendations WHO for air quality (maximum concentration of CO of 30mg/M3 for 24 hours periods and less than 10mg/ M3 for periods 8 hours of exposure), and the overall conversion efficiency in higher than 25%. [5]

Development of an Energy Poverty Line

► Download: Energy access, efficiency, and poverty: how many households are energy poor in Bangladesh? by: Barnes, Douglas F., Khandker, Shahidur R., Samad, Hussain A.

Abstract: Access to energy, especially modern sources, is a key to any development initiative. Based on cross-section data from a 2004 survey of some 2,300 households in rural Bangladesh, this paper studies the welfare impacts of household energy use, including that of modern energy, and estimates the household minimum energy requirement that could be used as a basis for an energy poverty line. The paper finds that although the use of both traditional (biomass energy burned in conventional stoves) and modern(electricity and kerosene) sources improves household consumption and income, the return on modern sources is 20 to 25 times higher than that on traditional sources. In addition, after comparing alternate measures of the energy poverty line, the paper finds that some 58 percent of rural households in Bangladesh are energy poor, compared with 45 percent that are income poor. The findings suggest that growth in electrification and adoption of efficient cooking stoves for biomass use can lower energy poverty in a climate-friendly way by reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Reducing energy poverty helps reduce income poverty as well.

Energy Poverty in the World Energy Outlook 2015

The Energy Outlook 2015 assesses two indicators of energy poverty at HH level:

- Lack of access to electricity

- Reliance on the traditional use of biomass for cooking

Greatest challenge: SSAfrica

- 35% electrification rate

- 2011: 696 mio relying on traditional biomass

► Download: World Energy Outlook 2015 Factsheet

► Download: World Energy Outlook 2010 (IEA)

► Download Presentation (Verena Brinkmann): IEA UNDP UNIDO Energy Poverty WEO 2010

Measuring Energy Poverty

Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI)

Abstract:

The provision of modern energy services is recognised as a critical foundation for sustainable development, and is central to the everyday lives of people. Effective policies to dramatically expand modern energy access need to be grounded in a robust information-base. Metrics that can be used for comparative purposes and to track progress towards targets therefore represent an essential support tool. This paper reviews the relevant literature, and discusses the adequacy and applicability of existing instruments to measure energy poverty. Drawing on those insights, it proposes a new composite index to measure energy poverty. Both the associated methodology and initial results for several African countries are discussed. Whereas most existing indicators and composite indices focus on assessing the access to energy, or the degree of development related to energy, our new index – the Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI) – focuses on the deprivation of access to modern energy services. It captures both the incidence and intensity of energy poverty, and provides a new tool to support policymaking.

► Download: Measuring energy poverty: Focusing on what matters (science direct), Supporting Sustainable Development through Knowledge (UN) by: Patrick Nussbaumer, Morgan Bazilian, Vijay Modi, and Kandeh K. Yumkella

Further Information

- Energy Access Figures on energypedia

- Figures on Energy Poverty on energypedia

- Access to Modern Energy on energypedia

- Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All) Global Tracking Framwork Report 2015

- IEA Energy Poverty

- The Guardian - Energy Poverty

News and comment on energy and fuel poverty in the developing world - OECD/IEA (2010): Energy Poverty. How to make modern energy access universal?

- http://www.africapowerltd.com/energy-poverty-and-access-to-power/

- "Energy poverty, or the lack of access to electricity and other basic energy services, affects nearly two-thirds of Sub-Saharan Africa. As the region's population continues to increase, so will the need to build a new energy system to grow with it, says Rose M. Mutiso. In a bold talk, she discusses how solutions like off-grid solar, wind farms and hydroelectric and geothermal power could create a high-energy future for Africa -- providing reliable electricity, creating jobs and raising incomes." Listen to her podcast (TEDSummit 2019 | July 2019): https://www.ted.com/talks/rose_m_mutiso_how_to_bring_affordable_sustainable_electricity_to_africa?rss=172BB350-0368

References

- ↑ IEA: http://www.iea.org/topics/energypoverty/

- ↑ energypedia:https://energypedia.info/wiki/Access_to_Modern_Energy#Overview

- ↑ Bazilian et al. 2010. Measuring Energy Access: Supporting a Global Target. http://www.unido.org/index.php?id=1000598

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 D. Barnes: The Concept of Energy Poverty, http://www.energyfordevelopment.com/2010/06/energy-poverty.html Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "barnes" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "barnes" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "barnes" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Practical Action: Energy Poverty: Estimating the Level of Energy Poverty in Sri Lanka, http://practicalaction.org/docs/region_south_asia/energy-poverty-in-sri-lanka-2008.pdf