Difference between revisions of "End-User Finance in Mozambique"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) m Tag: 2017 source edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Back to Mozambique Portal}} | {{Back to Mozambique Portal}} | ||

| + | {{Portuguese Version|Financiamento_para_o_Utilizador_Final_em_Moçambique}} | ||

| + | |||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Formal end-user finance is difficult to access for most Mozambicans due to very limited availability, especially in rural areas. Non-bank financial products such as mobile money, however, have seen a major uptake over the last five years. Launched in 2011, mobile money is used by one in every four adults.<ref name=":0">[https://drive.google.com/file/d/1TYp_gAuemR2rUVUNWeYyA2N9hG5U7qUS/view FinScope (2020): Consumer Survey Mozambique 2019.] </ref> | Formal end-user finance is difficult to access for most Mozambicans due to very limited availability, especially in rural areas. Non-bank financial products such as mobile money, however, have seen a major uptake over the last five years. Launched in 2011, mobile money is used by one in every four adults.<ref name=":0">[https://drive.google.com/file/d/1TYp_gAuemR2rUVUNWeYyA2N9hG5U7qUS/view FinScope (2020): Consumer Survey Mozambique 2019.] </ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:50, 7 March 2022

Introduction

Formal end-user finance is difficult to access for most Mozambicans due to very limited availability, especially in rural areas. Non-bank financial products such as mobile money, however, have seen a major uptake over the last five years. Launched in 2011, mobile money is used by one in every four adults.[1]

To overcome financial barriers and make energy access technologies available to different customer segments, a couple of different end-user finance approaches can be applied by companies and other stakeholders as presented in this article. However, purchasing power, budget constraints, and willingness to pay of potential customers are key variables that need to be assessed and kept in mind.

Access to Consumer Finance

According to the latest FinScope report for Mozambique, in 2019, 21% of Mozambicans had access to formal institutions such as banks; 41% had access to other formal non-bank institutes, mainly mobile money but also including micro finance, saving and credit cooperatives, cooperatives, savings and credit operators, and pension funds; 32% had access to informal savings groups called Xitiques, and 46% did not have access to any.[1]

Out of the 21% of the adult population in Mozambique that had a bank account, 41% lived in urban and 10% in rural areas. 60% of the rural population is excluded from any formal or informal financial products or services compared to one fifth of the urban population.[2]

Most financial services are concentrated in Maputo City and Maputo Province. While in these provinces (Maputo City and Maputo Province) only 11% respective 21% of adults are financially excluded; in provinces such as Tete, Manica, Zambézia, and Niassa more than 50% of adults don’t have access to any financial products and services.[1]

For a provincial distribution of bank branches as of 2019, see the chapter on financing opportunities for energy access companies.

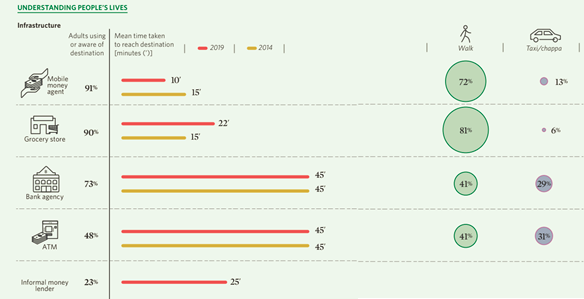

This regional imbalance is also mirrored in the fact that nearly half of the population uses or is aware of the next Automated Teller Machine (ATM), and of those who use or know it need 45 minutes mean time to reach it (mainly by walking). Similarly, almost three quarter of the people use or are aware of the next bank agency, which is at a 45 minutes mean time distance[2].

The most available and accessible are mobile money agents, which most people use or are aware of their location and only take a short walk to reach them.

This makes mobile money the most used financial product in Mozambique, with 29% of the population having a mobile money account. This is a huge jump compared to the 3% in 2014. There is almost no difference in terms of gender, with 55% of male have access to mobile phone compared to 54% of women. The most common use of mobile money is for cash withdrawals (91%), cash deposits (81%) and cash transfer (72%). 27% use it for utility payments and 9% for goods payment.[2]

Credit Lines in Place

Banco Comercial e de Investimentos (BCI) SUPER credit line is designed for institutions or companies that adopt integrated renewable energy systems by purchasing renewable energy equipment for productive uses in agribusiness, PV systems for the commercial sector, or waste to energy technologies.

Target end-users are micro, small, medium enterprises, associations, cooperatives and NGOs.

The credit line will be available until 31 March 2023 or until the amount available for financing (1 million USD) is reached. BCI funds up to 75% of the project or equipment to be acquired under the facility, with a max of MZN 3.5 Million and at a 7.5% interest rate.[3][4][5]

Savings and Credit

More than half of Mozambican adults (55%) do not save money. 25% even don’t know the meaning of the term “saving”. Those who save, do it mostly at home (32%) or with informal saving groups (27%). In general, urban adults rather tend to save compared to adults in rural areas, more men than women are saving.[1]

According to the 2019 FinScope survey, only 7% of Mozambican adults had borrowed money in the last 12 months. 4% borrowed formally from banks, 2% informally, and 1% within family or from friends.[1]

End-user Finance Approaches for Off-grid Technologies

Pay-as-you-go (PAYGO)

PAYGO is a financing model, where end users pay for products or services in small instalments or whenever they are financially liquid instead of directly paying the full price in cash upfront. Under PAYGO, the companies not only provide product and services but also the necessary finance to consumers. Customers usually pay 10-20% as upfront cost and the rest as loans over a period of 1-2 years until they own the system. Payments are typically made via mobile money. If the fee is not paid, the system blocks automatically and cannot be used again until credit has been purchased.

Read more about PAYGO here.

In Mozambique, PAYGO approaches are rather new and not yet well established. The first solar company offering PAYGO schemes started operations in Maputo, in 2016.[6] Even though mobile penetration rate with 50-60% (according to different sources) is quite high[7][6], only 29% of the adult population has a mobile money account[1], hampering the proliferation of PAYGO models.

Another barrier for PAYGO has been the lack of clear leasing regulations for non-financial institutions. To overcome this obstacle, most companies remain the owner of the system and charge customers a fee for using it.[6]

Energy-as-a-service (EaaS)

Energy-as-a-service (also “Fee-for-Service”) is a business model whereby customers pay a monthly fee for an energy service without having any upfront cost. The energy service provider remains the owner of the system and is responsible for repair and maintenance. The solar home system installed on a home, for instance, is owned by the company and the household pays a monthly fee for using the generated electricity.[8]

If the weekly/monthly/daily fee is not paid, the system is blocked automatically and cannot be used again until credit has been purchased.

As mentioned above, in Mozambique, this business model is used by many PAYGO companies to overcome the obstacle of lacking leasing regulations for non-financial institutions.

Microfinance

In general, microfinance is one of the most common financing concepts for small‐scale decentralized/off-grid renewable energy projects worldwide. Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) provide loans to households, communities or small businesses mainly for productive purposes or for buying products and services.

- Read more about microfinance in general.

- Read more about microfinance for cookstoves.

In Mozambique, the microfinance sector is very small and concentrates predominantly on Maputo City and Maputo Province. High interest rates make credit from Micro Finance Institutions (MFI) very expensive. In 2015, none of the microfinance institutions (MFI) were known to have a lending programme for solar.[9]

Results-based Finance

Results-Based Financing (RBF) is a very broad term, with a wide range of instruments being piloted or implemented. While it usually benefits companies that have achieved a predefined sales goal, it can also be used to subsidise energy products and services. These RBF approaches are usually provided and paid for by international or national funds, aid or development organisations and implemented in cooperation with local NGOs or companies.

Examples of results-based financing instruments include:

- Output-based aid (OBA) links the payment of funds to the delivery of 'outputs' like connection to electricity grids or the provision of solar home systems. Service delivery is contracted out to a third party, which receives a subsidy to complement the portion of user fees that poor households are not able to afford. The outputs are verified independently after the services have been delivered, and before payment;

- Advance market commitments, whereby a fixed quantity or price is offered for a product or service over a relatively short period of time in order to stimulate a market response;

- Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) target individuals or households by paying them a predefined amount of money against complying with specific requirements. CCTs are thus instruments which can be used to encourage certain social behaviours, such as the adoption and use of improved cookstoves;

- Voucher schemes are an alternative way of providing capital or revenue incentives for a particular product or service. Free or subsidised-fee vouchers are offered to households, which can use the voucher for accredited retailers or service providers. These companies are then reimbursed for products and services delivered. This way, vouchers are stimulating both supply and demand side.

In Mozambique, there are several donor funded programmes and funds that provide results-based finance to energy access companies. Click here for an overview.

Further Reading

- Republic of Mozambique: National Financial Inclusion Strategy 2016-2022.

- FinScope (2020): Consumer Survey Highlights. Mozambique 2019.

- FinScope (2020): Consumer Survey Mozambique 2019.

- Financing and Funding Portal on energypedia

- Fee-For-Service or Pay-As-You-Go Concepts for Photovoltaic Systems

- Results-Based Financing (RBF)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 FinScope (2020): Consumer Survey Mozambique 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 FinScope (2020): Consumer Survey Highlights. Mozambique 2019.

- ↑ https://amer.org.mz/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/LINHA-CREDITO-BCI-SUPER.pdf

- ↑ https://www.bci.co.mz/bci-exclusivo-pme/ (accessed in Oct 2021)

- ↑ https://www.tse4allm.org.mz/index.php/en/credito-super/perguntas-frequentes-credito-super

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Economic Consulting Associates, GreenLight (2018): Off-Grid Solar Market Assessment in Mozambique, accessed May 2021.

- ↑ https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-mozambique

- ↑ IRENA (2020): Innovation landscape brief: Energy as a Service. Accessed in May 2021

- ↑ Overseas Development Institute (2016): Accelerating access to electricity in Africa with off-grid solar. Off-grid solar country briefing: Mozambique.