Difference between revisions of "Solar Home Systems (SHS)"

***** (***** | *****) m Tag: 2017 source edit |

***** (***** | *****) m Tag: 2017 source edit |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

*Also see this publication: [[Publication - Security of Solar Modules]] | *Also see this publication: [[Publication - Security of Solar Modules]] | ||

| − | <div class="box box- | + | <div class="box box-purple">Test</div> |

= Project Examples = | = Project Examples = | ||

Revision as of 08:13, 1 April 2022

Overview

Solar home systems (SHS) are stand-alone photovoltaic systems that offer a cost-effective mode of supplying amenity power for lighting and appliances to remote off-grid households. In rural areas, that are not connected to the grid, SHS can be used to meet a household's energy demand fulfilling basic electric needs. Globally SHS provide power to hundreds of thousands of households in remote locations where electrification by the grid is not feasible[1]. SHS usually operate at a rated voltage of 12 V direct current (DC) and provide power for low power DC appliances such as lights, radios and small TVs for about three to five hours a day. Furthermore they use appliances such as cables, switches, mounts, and structural parts and power conditioners / inverters, which change 12/ 24 V power to 240VAC power for larger appliances[1]. SHS are best used with efficient appliances so as to limit the size of the array.

A SHS typically includes one or more PV modules consisting of solar cells, a charge controller which distributes power and protects the batteries and appliances from damage and at least one battery to store energy for use when the sun is not shining.

They contribute to the improvement of the standard of living by:

- reducing indoor air pollution and therefore improving health as they replace kerosene lamps,

- providing lighting for home study,

- giving the possibility of working at night and

- facilitating the access to information and communication (radio, TV, mobile phone charging).

Furthermore, SHS avoid greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the use of conventional energy resources like kerosene, gas or dry cell batteries or replacing diesel generators for electricity generation. Further impacts of renewable energies, such as SHS, can be found in the Report on Impacts.

Stand-alone photovoltaic systems can also be used to provide electricity for health stations to operate lamps during night and a refrigerator for vaccines and medicines to better serve the community.

Technical Standards for Solar Home Systems (SHS)

To assure the quality of a photovoltaic power system and its correct functioning and guarantee costumers' satisfaction, it is important that the components of the system and the system as a whole meet certain requirements.

The GIZ prepared a publication which gives an overview of different standardisation activities and existing standards that are relevant for solar home systems (SHS) and rural health power supply systems (RHS), titled Technical Standards for Solar Home Systems (SHS).

Planning, Installation and Maintenance of Solar Home Systems (SHS)

Before installing a photovoltaic (PV) SHS, its size has to be calculated according to different assumptions, such as measurement of solar radiation, solar insolation and power demand. Regarding the installation process, Solar Home Systems have to be installed by a trained technician who knows how to handle its different parts. Thus, aspects of maintenance and a solar technical training manual is presented: Planning, Installation and Maintenance of SHS.

Costs

Typical systems costs in the Eastern Africa region range between US$ 170 for a 12 Wp system and up to US$ 2,000 for a 150 Wp system. For developed countries the average cost per installed watt for a residential sized system is about US$ 6.50 to US$ 7.50, including panels, inverters, mounts, and electrical items. In Eastern Africa the cost is 2-3 times higher[1].

-> For more detailed information on SHS costs click here.

Tools to Prevent Theft of Panels

- For more information please see here.

- Also see this publication: Publication - Security of Solar Modules

Project Examples

Case Study from Fosera (Learn more about our Featured Content)

After more than two decades spent building up a loyal customer base, Teddy Hangandu, a tailor in Lusaka’s Luangwa Compound, found himself falling into a slump.

- “Before I bought the solar lights, I used to find it hard to work at night. This resulted in not meeting customer deadlines especially when you have a number of customers.” Teddy Hangandu

If you are living in a house without power, work comes to a standstill once the sun goes down. But Teddy’s clientele wants their clothing when they want it, sun up or sundown. With this in mind, Teddy tried using paraffin lamps at nighttime, but this wound up costing him K50 (about 2.80$) a week on fuel.

These lamps also pose serious hazards;

● The paraffin lamps give off poisonous fumes that badly affect the respiratory system. ● Paraffin is highly flammable, and if knocked over, the lamp can cause serious house fires. ● Impure paraffin has been known to explode without warning.

Aware of these dangers and unhappy about spending money on fuel instead of more valuable activities, Teddy vented his frustrations to a friend. Luckily, his friend, a VITALITE customer, introduced [en1] him to the Lighting Plus Solar Kit – a product that is particularly adapted to the needs of people with limited or no access to grid electricity in Zambia.

[en1]How do you identify customers? Distribution network?

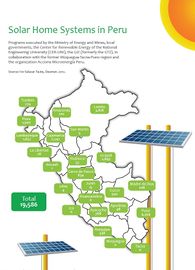

Solar Home Systems in Peru

In Peru, a series of renewable energy projects have been implemented, predominantly using hydropower and solar photovoltaics (PV). Solar energy is a reliable source because it involves no moving parts, is easily applicable to the geographic conditions of rural populations, and relevant information is readily available.

About 21% of the population of the country is without electricity and the only way for these people to access it is if existing networks are extended or renewable energy projects implemented. Thus, the General Directorate of Rural Electrification (DGER) estimates that approximately 2.48 million people in Peru could be provided with electricity through renewable energy.

Photovoltaics have become, in recent years, a viable option for rural and isolated populations, because their electric generation costs have become competitive compared to other options, such as the extension of the conventional power grid or the use of diesel generators.

In the early 90s, the number of rural electrification projects in various countries, including Peru, increased significantly. The beginning of this new era in our country coincided with the formation of several initiatives, among which were those of the GTZ (now GIZ). In conjunction with the former Tacna-Moquegua-Puno Region, they promoted various applications of PV technology, trained locals and established funding mechanisms for the purchase of photovoltaic systems.

At the same time, the national government, through the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM), initiated their first pilot project in the town of San Francisco, Pucallpa, which involved the installation of 134 Solar Home Systems (SHS) of 53 Wp. This project was expanded in the following years to the point that they put into operation about 1500 SHS in various parts of the country.

Also, the MEM, with the Renewable Energy Center of the National University of Engineering (CER-UNI), promoted a pilot project, that offered credit for the purchase and installation of SHS, primarily to families living on the islands of Lake Titicaca. This included after-sales service for a year. Through this initiative about 500 SHS were installed. The MEM also implemented pilot projects to install photovoltaic and wind systems of 1 kW in community centers and health posts in eight isolated parts of the country.

The experience gained from these projects has served to improve the implementation of future PV projects, through the program “Photovoltaic Based Rural Electrification in Peru," funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the MEM and in partnership with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), which has led to the following:

- Development of a Solar Energy Atlas through an agreement with the National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology (Senamhi);

- Creation of a database of geographic information of PV systems installed;

- Training at different levels (consumer, preventive and corrective maintenance technicians, installers, authorities and the general public) through workshops and the publication of manuals, posters, among others;

- Institutionalization of the certification process, by strengthening two national laboratories and approving the regulation "Technical Specifications and Evaluation Procedures for Photovoltaic Systems and Components";

- Development of management models for SHS and pilot projects;

- Implementation of pilot projects and hybrid wind-solar systems of 150 W;

The project facilitated the installation of 4200 SHS in the Amazonian regions of Cajamarca, Loreto, Ucayali and Pasco; they were later transferred to the Electrical Infrastructure Management Company (ADINELSA) for administration.

- The community center in the village of Santa Lucia has electricity through a SHS.

The Photovoltaic Rate:

Given the large number of SHS installed in various parts of the country, the Supervisory Agency for Investment in Energy and Mining (OSINERGMIN) established a fixed rate for photovoltaics.

This rate applies to electric generation between 50 and 320 Wp. However, about 80% of the users of this system receive state-subsidized rates, which have substantially improved the sustainability of the projects, as they are managed by governmental, non-governmental and private entities.

Finally, it is important to note that the solar energy market has generated about 14 million Peruvian Nuevos Soles (about 5.4 million dollars) between 2010 and 2011, either for the replacement of components or the implementation of new projects in both the private and public sectors.

In 2010 and 2011, public institutions, from the MEM to district municipalities, invested about 5 million Peruvian Nuevos Soles (about 1.9 million dollars) in new projects and it is expected that this year investment will continue to grow, bringing renewable energy to the forefront in rural areas, which will aid its development.[2]

Solar Home System in Rural Bangladesh

For information about the impact of solar home system in rural Bangladesh, see Impact of Solar Home System in Rural Bangladesh.pdf and Overcoming Barriers to Rural Electrification - Example of Solar Home System in Bangladesh.pdf.

Solar Home System in Nigeria

Nigeria is a sub-Saharan Africa Country. It has the highest number of people without electricity in the region. With the Solar home System, the number of people with a power supply has increased. The Federal Government of Nigeria through its Rural Electrification Agent Project has shown her commitment to the distribution of Solar Home Systems to reduce pollution and increase remote and rural electrification in the country. Partnership with solar companies in Nigeria has made the project impactful.

Solar Home System in Germany

So called "Balkonkraftwerke" (literally meaning: energy-producing systems for your own balcony) are small solar home systems producing electricity. Legal installation has been made considerably easier by a new VDE guideline in 2017[3] (which came into force in 2018). Since then, private users have been allowed to put systems into operation themselves as long as they do not generate more than 600 watts of power and register the system.

However, there are still legal grey areas that have not yet been finally clarified, e.g. whether the generated electricity has to be fed in via a special energy socket (Wieland) or whether a normal socket (Schucko) is sufficient.

Further Information

- Solar Portal on energypedia

- Market for Solar Home Systems (SHS)

- Solar Home System (SHS) Costs

- Financing Models for Solar Home Systems

- Subsidies for Solar Home Systems

- Monitoring of Solar Home System (SHS)

- Technical Standards for Solar Home Systems (SHS)

- A Discussion of Solar Home Systems in Developing Countries, Including a Course Scope for SHS.pdf

- practicalaction.org - cable selection in small off-grid solar energy installations

- practicalaction.org - small scale off-grid solar pv installation manual

- practicalaction.org - solar photovoltaic system design info-sheet

References

The article on SHS in Peru was originally published by EnDev Peru in the second issue of Amaray Magazine published in November 2012.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 GTZ (2007): Eastern Africa Resource Base: GTZ Online Regional Energy Resource Base: Regional and Country Specific Energy Resource Database: I - Energy Technology

- ↑ Peru: Amaray Magazine.

- ↑ VDE (2017): Mini-PV-Anlagen: VDE|DKE bahnt Weg für sicheren Betrieb. https://www.vde.com/de/presse/pressemitteilungen/mini-pv-anlagen#.