Content of Planning Cookstove Interventions

Basics | Policy Advice | Planning | Designing and Implementing (ICS Supply)| Technologies and Practices | Designing and Implementing (Woodfuel Supply)| Climate Change

Overview

There is no blueprint for the planning of an improved cooking stoves (ICS) intervention. Even after more than 30 years of GIZ cooking energy promotion, the concepts of ICS intervention to date still vary from country to country. This is mainly due to the fact that the frame conditions for the planning often look different.

While the answers are always circumstantial and specific, there are general important questions which need to be answered in any ICS planning process. These questions are sorted by important aspects of the content of planning (location, ICS market, technology, production system, partners, service providers etc.). It is recommended to consider these questions in the inception study and the preparation of the inception workshop.

Selection of Project Location

The selection of the project location or the geographic area in which the intervention will be implemented is often not only determined by technical considerations.

In some cases, there is already a positive pre-selection to be considered:

- the political partner has clear (political?) priorities where the intervention should be located.

- Cooking energy interventions are embedded in territorial project approaches (e.g. promotion of rural development in the region X of country Z) with clear defined geographic boundaries of the intervention.

In other cases, the choice of location is limited by factors of exclusion:

- certain areas are “no go zones” because of political instability or poor living conditions for project staff.

- Due to donor coordination, certain areas of the country are already allocated to other development agents;

Provided that the selection of the intervention area is mainly based on "technical matters", the following table provides an overview on factors which should be considered in the selection of the project area. Their potential impact on the selection is assessed based on GIZ’s long term project experiences. However, in a specific case the judgment can be different.

The potential impact on the implementation is structured by the following categories:

- More efficiency = Reaching more people for the same money

- More effectiveness = Higher relevance of development impact

- More sustainability = change process more durable

| Factors |

Potential influence on selection | Potential impact on implementation |

|---|---|---|

|

Population:

|

|

|

|

Households:

|

|

|

|

Current access to the different fuels used:

|

|

|

|

Dynamics of population, readiness for change

|

|

|

| Accessibility to markets and services |

|

|

| Control over budget for cooking energy |

|

|

In the inception study, the factors listed in the table should be investigated and analyzed. Not all of them will be relevant in all cases. The potential impact on the selection and the impact on the implementation are just examples from field practice. They do not preempt the case study which may deliver other results. They shall rather illustrate the kind of consideration to be made when selecting an intervention area.

Selection of Potential Improved Cookstove (ICS) Markets

The potential ICS markets can be ranked in various dimensions:

- Purchase power of customer groups

- Size of the market

- Access of potential customers to the market / Difficulty to reach customers

- Likeliness to find a product that suits the demand of the potential customers (existing product or need for product development)

- Competition on the market through other players

- Possibility to scale up existing efforts

Based on these criteria, the potential ICS markets can be compared and prioritized. However, it needs to be verified if the “best market” is also relevant from the perspective of the underlying development goals (see frame conditions for planning cooking energy interventions).

A small market may be easy and efficient to penetrate. However, this may not be a very effective approach as that market might not be too small or irrelevant for the development of the country.

For the selection of the potential ICS market it is important to learn more about the targeted market segments and the potential producers. Assessing market opportunities is not easy and it is worthwhile to get assistance from an economist or marketing specialist to develop the business case. See also commercialisation of improved stoves.

Some important questions are listed below:

- What are the sources of income for the target group?

- What is the level of cash income and its seasonal distribution?

- Who is deciding on how the money of the household is spent? What fraction of the household income of the target group is spent on fuel (if commercial access and not collected)?

- What are other large cost factors in the household budget?

- For which type of local artisanal products and services are people prepared to pay cash?

- Are clay and mud products also considered a commodity/payable service or only metal and stone products?

- What are other investment goods to be found in target households? (e.g. radio, cell phone, solar lantern, torch, TV, solar home system, biogas digester)

- What are common distribution systems for investment goods in the target area? (e.g. markets, kiosks or shops, roadside sales, mobile vendors, associations/cooperatives)

- Who could become a distributer of ICS in the intervention area?

- What would be the interest to start selling ICS?

- Are there any experiences with ICS being sold on the market?

- Which kind of stoves?

- Who are the customers?

- How is the distribution network organized?

- How can stoves be transported to the users?

- How accessible are markets?

- Are there any examples of successful marketing campaigns in the region?

- And/or somewhere else in the country?

- Are there experiences with past, present or future "free handout" or "subsidy" initiatives for development goods (e.g. Mosquito-nets, agricultural inputs, stoves, etc.) in the target area?

- How does that impact on people’s perspective on a market access to an ICS?

- Are people really prepared to pay for an ICS? And how much?

- Are there current or future initiatives to use stoves in carbon financed programs in the country?

- Are the funds of the carbon market used to subsidise the retail price of the stoves?

The different business cases should be discussed and ranked in the process of the inception workshop or at a later stage of the stakeholder consultation process.

Selection of Technology

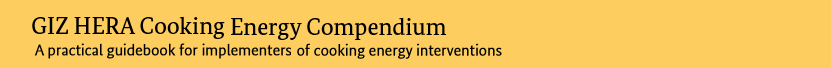

Worldwide, a wide range of improved cook stoves exist. They differ in many aspects:

- Fuel: firewood, charcoal, other solid biomass, liquid biomass, biogas, non-biomass fuels;

- Mobility: portable or fixed stoves

- Flames: one flame stove or multiple flame stove

- Pots: (a) one pot only at a time or multiple pots used at the same time; (b) only usable for a specific pot (sunken pot concept) or usable for a variety of pot sizes and shapes;

- Material: mud, fired clay, bricks, cement/concrete, metal, isolation materials (vermiculite, ceramic wool, refractory bricks, air…);

- Chimney: smoke reduction (without chimney) or smoke extraction (with chimney);

- Dimension: Tea preparation stove (for app. 1-2l), household size stove (for app. 3-15l), restaurant size (for app. 15-50l), large institutional stove (for app. 50-300l)

All these differences influence the perception of the “convenience of use” by potential user groups.

-> An overview on ICS examples is given here: cooking energy technologies and practices.

There is no standard procedure to identify which technology might be most successful on the market. On the one hand it has often been observed that “evolution” of existing baseline technologies is more acceptable and feasible than “revolution” (e.g. bringing in a completely new stove and fuel concept). On the other hand, the establishment of a commercial supply chain might be more feasible with a “modern/strange” product (e.g. a portable metal stove) rather than with a modification of an existing self-help product (e.g. an improve mud stove), if there is already a long tradition of local non-cash stove building.

Many interventions resorted to offering a range of stoves to the target groups and let them have the choice according to their needs, capabilities and preferences. Sometimes you start with one or two products and then, after realizing additional market opportunities, additional products are taken on board.

In the selection of technologies, the needs and perception of both potential customers and users on the one hand and potential producers and traders on the other hand have to be taken into consideration.

- A stove which works well and is very cheap, but which will not give the producer any profit, will not be produced for sale.

- A high-end efficient, durable and beautiful stove which is highly profitable for the producer will not deliver a large development impact if the target group is not prepared to spend so much money for its purchase.

New technologies often have to be adapted to the local requirements. It is important to reserve time and resources for several loops between producers and users of a new ICS to make sure that the stove model is well accepted and matured before the actual market introduction. In the reality, there are tremendous time pressures which may tempt one to take short cuts. However, this might be the wrong place to cut corners.

“Why should poor people spend their little cash to buy an improved stove?”

This question has to be answered through the perspective of the potential buyers to investigate if there is a business case. User group discussions or test sales can assist to verify the strength of an ICS market case.

| Factors considered by target group |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Convenience issues:

|

|

|

Financial issues:

|

|

|

Status issues:

|

|

|

Access and vulnerability issues:

|

|

In the past, the following questions have helped GIZ to identify the right technology choice. They might be useful for the inception study:

- Which are the most common dishes prepared by households?

- How are they prepared?

- What type of heat (high power, simmering power...) do they require in which phase of the preparation?

- Which cooking utensils are used (number and types of stoves used in the household for which purposes; number, size, shape and material of cooking pots are used in the households for which cooking purposes)?

- What is the percentage of households in the target communities which do already use any kind of ICS?

- Where is cooking taking place (inside or outside, kitchen design,...)?

- When is cooking taking place (time, intensity and frequency of cooking)?

- fuel management practices (types of fuel used, access, storage, preparation, usage of fuel, current efficiency of use)?;

- kitchen management practices (preparation of foods, type and sizes of cooking pots, usage of lids, ...)?;

- stove management (one fire or more fires parallel for one meal; management of fuel in the stove while cooking)?;

- For which other purposes is the stove used beyond cooking (e.g. water for washing, preparation of animal feed, commercial activities, etc.)?

- What - in the perception of the users - are the advantages and disadvantages of the currently used cooking energy system(s): e.g. purchase or owner build/ price; convenience of use etc.?

- What are the expectation of different target groups on a "good cooking energy solution" (e.g. height of the stove, design, speed of cooking, smoke, size, intensity of attention on the fuel management, need for maintenance, cost, live span, portability, heat generation/emissions, light emission, "modernity"/prestige)?

- Are there ICS models from other (neighboring) countries with similar cooking practices which could be introduced and adjusted?

Selection of Production System

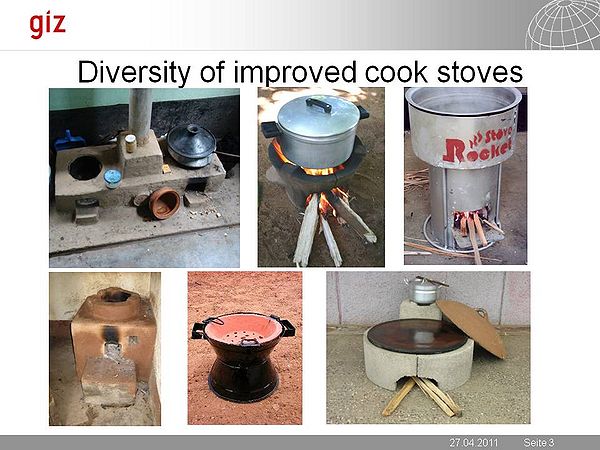

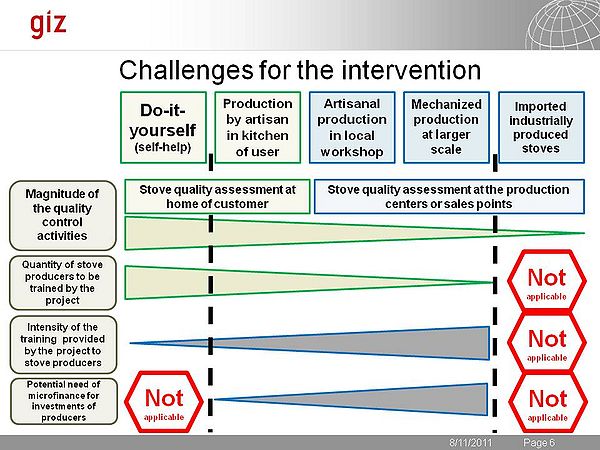

There is a close link between the modes of production and the use of tools, division of labor, use of mechanical and electrical machines, etc. These differences influence the quality, quantity, vulnerability and the cost of production. The extreme cases are on the one hand the “do-it-yourself” self-help stove and on the other hand the industrially produced stoves imported from China. In between, there are fixed stove build by trained artisans, artisanal portable stoves build in local workshops and more or less mechanized production centers of portable ICS at national level.

Production systems (and their typical products) can differ on various characteristics:

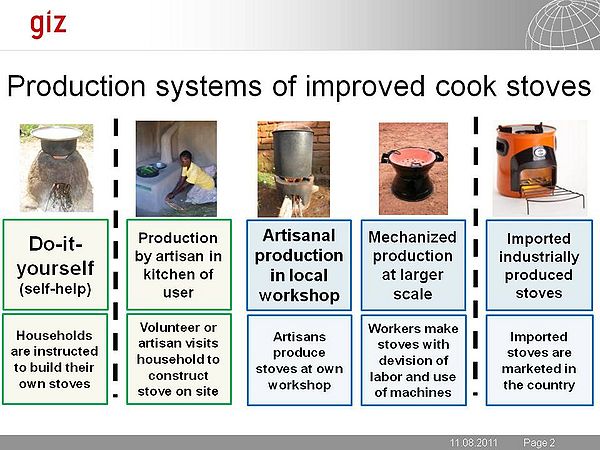

- Professionalism of stove production:

The routine of producing a stove is increasing with the number of stoves produced. Self-help stoves are built once in a while when the lifespan of the stove has expired. In contrast, workers in (semi-)industrial production centers are highly specialized in producing stoves. Artisanal production (both of portable and fixed stoves) can reach different levels of professionalism (seasonal, part-time or full time activity). - Design drift:

Improved cook stoves are promising potential customers a relative level of performance (“saves x% fuel as compared to the baseline stove”). If each ICS has its own shape and design, it is likely that they also perform differently. Hence the customers may be dissatisfied if their stove does not perform according to their expectation. Products must perform to a predictable level if they shall succeed as a commercial product. To avoid design-drift, it is necessary to standardize the production process. This means the application of devices which help to reduce the variation of the stove quality in the production process. There are a variety of possibilities to achieve standardisation such as the use of moulds/templates or the use of mechanical or electrical machines. For fixed stoves, standardisation is a challenge. They are build “on site” which makes the use of machines difficult. Any tool, mould or template has to be transported to the customer which makes standardisation cumbersome. A solution can be the use of standardised, pre-fabricated parts which are just assembled on site. Another “hybrid” solution is the import of industrially produced flat packs of parts for the assembly in country. - Durability:

Self-help stoves are often of poor quality with a very short life-span. In contrast, industrial products often come with a warranty of several years. The lifespan of artisanal products is strongly influenced by (1) the quality of the material used, (2) the quality of the production process, (3) the handling of the stove in the retailing process, and (4) the way the device is used in the household. There is still need to develop a methodology to measure the durability of stoves. - Maintenance:

Fixed stoves are often build of materials which can be locally found (mud, bricks, clay, sand etc.). They tend to require regular maintenance such as smearing the surface to cover small cracks. Portable stoves tend to be made of fired clay or metal which do not require much maintenance. - “Efficiency” (technical potential):

Improved cook stoves are promoted mostly with the promise that their usage will reduce the specific fuel consumption of a household as compared to traditional stoves (preparing the same meal). Hence the direct comparison with the baseline stove is of utmost importance. Comparisons between different efficient cook stoves are commonly based on water boiling tests or controlled cooking tests (click here for more information on testing). Fixed stoves tend to be rather high mass stoves as compared to most portable stoves. Hence for shorter cooking tasks (e.g. 1h), portable stoves consume less fuel than fixed stoves as it takes less energy to heat up their material. Other foods like beans require several hours of preparation. In this case, high mass stoves might be of an advantage as – once their mass is heated - they require less fuel for the simmering phase as compared to low mass stoves. - Emission (technical potential):

Imported industrial stoves are tuned under the emission hood to a design with minimum of emissions such as PM or CO. In contrast, self-help stoves do not have specific design principles which would allow for significant emission reductions. Artisanal fixed or portable stoves may have some potential for emission reduction but not as much as stoves which are particularly designed for that purpose. However, the design of the kitchen and the user behavior are much more relevant for the scale of emissions rather than the stove design itself. A three-stone fire with dry wood in a well ventilated room will cause less indoor air pollution than an industrial stove used with wet wood in a closed room. Hence we can only compare the technical potential, whereas the reality in the households is much more influenced by the user’s behaviour (click here for more information on firewood management). - Retail price:

Self help stoves only require the opportunity costs of the materials and the labour. Imported industrial stoves are so far much more expensive as locally produced stoves if marketed without subsidies. Artisanal products have various prices depending on the costs of materials, labor input, competitive other income opportunities, relationship to the customer, distance to the market, season/purchase power of customers, cash need of the producer etc. GIZ has observed that rural households are more prepared to pay cash for a stove if it is build out of materials they cannot access themselves (e.g. metal, fired clay or cement). The commercialisation of improved mud stoves has often meet difficulties. They are rather subject to self-help or neighbourhood-help arrangements with “in kind” compensations such as food or livestock.

These differences can pose challenges for an ICS intervention:

- Magnitude of the quality control activities:

Portable stoves can be controlled at the production centers or the sales points. Fixed stoves can only be controlled at the home of the user. Thus, the quality control for self-help stoves or artisanal fixed stoves requires a huge outreach into the homes of the users, which is costly and cumbersome. Imported industrially produced stoves already arrive with a certain level of quality control. At the off-loading from the container, breakages have to be detected. Portable artisanal stoves can be checked at the place of production. For the same sample size, the effort of monitoring is far less as compared to fixed stoves. - Quantity of producers to be trained by the project:

Industrial cook stoves do not require any training of producers by the project as this is taken care of by the supplier of the stoves. For a “do-it yourself” approach, every household of the target group needs to be instructed. Commonly, a “trainer of trainers of volunteers” cascade concept is applied for this purpose. In contrast, artisans usually are all trained directly by the project or qualified training providers. As artisans supply stoves to a larger number of households, less producers needs to be trained as compared to the self-help approach. - Intensity of the producer training provided by the project:

Self help stoves are commonly simple stove designs. Hence households do not require an intensive training. The more complex the stove design and the more the production system is mechanised, the higher the need of qualified trainees and the more intense the training program. Again, imported stoves relieve the project from training activities for stove producers. - Potential need of micro finance for investments of stove producers:

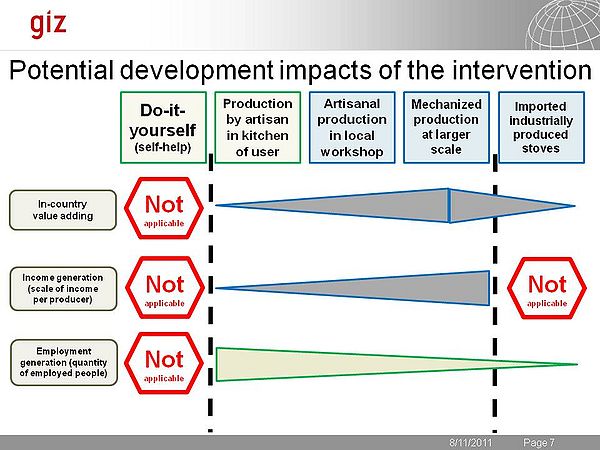

The start-up of stove production is linked to investments. The more the production system is mechanized, the higher the investment barrier is. The formal banking sector often does not permit the access of producers to formal sector loans. In such cases, the micro-finance sector can offer an alternative (see microfinance). Self help stoves do not require loans for investments in production infrastructure. Neither do producers of imported industrially produced stoves. Different production systems (and their products) have different potential impacts on some selected development goals:

- In-country value adding:

The promotion of improved cook stoves is sometimes employed as a mean to foster local economic development. An important aspect for this intention is the value adding which is associated with the production and marketing of ICS. Self-help stoves do not contribute to value adding. Imported stove are already produced before entering the country. Hence the larger part of the value adding has taken place outside the country. The value adding effect of artisanal production of stoves at the home of a user or in the workshop is difficult to estimate as it depends on the cost of the inputs as compared to the sales. It is assumed that large mechanized workshops are in the position to generate more value adding as compared to artisanal stove builders due to the level of efficiency in the production system. - Income generation (scale of income per producer):

Artisanal stove production of both fixed and portable stoves in rural areas is often not a full time employment but a seasonal activity. In the agricultural off season, stoves are produced and sold. This is also the time when the customers have money based on the income from selling agricultural produces. Mechanized production centers tend to be permanent operating with full time employees. It is assumed that a full time employee receives a higher income from the stoves work as compared to a part time artisan. - Employment generation (quantity of employed people):

A highly efficient production system requires less employees for the production of the same number of stoves. Hence the importation of ready-made stoves offers the least number of jobs. This applies also for the self-help stoves as they are not commercial. The efficiency of part-time local artisans is not as high as in mechanized production centers. Hence it is plausible to assume that for the same amount of stoves sold, the number of people who can find employment will be higher in artisanal production concepts as compared to mechanized production centers.

Questions for the inception study:

If a local production of stoves is to be considered in the planning process, the inception study has to provide information on the potentials for such a development path.

Please consider:

- Does the target group require a portable or a fixed stove?

- This relates to the question if people are cooking always inside their house/kitchen or if they often change the places of cooking e.g. because they are mostly cooking outside their homes?

- Which types of stoves are already existing in the intervention area?

- Who is currently producing stoves in the region? What are their skills? What is their capacity (how many stoves/ month)?

- Which materials could be used? (e.g. availability, accessibility including cost, vulnerability of access, risks of access);

- Which materials have to be purchased from somewhere else? How easy is this?

- What are the capacities for stove production? (e.g. kind of artisans, quantity, skill level, business orientation, openness to new products, level of organization, working capital, skills development mechanisms)

- What are the criteria for identifying potential new producers? (e.g. income level; successfully marketed products; interest in new products; production skills) How many producers would you need for the region?

- What kinds of support and /or training do they need? Are there credit schemes to support producers – particularly for large-scale dissemination? How easy is it for producers to access these schemes?

- Is there an opportunity to involve women in the production and marketing of ICS? Are there restrictions in terms of materials to work with or places to work in?

|

Points to consider:

|

Selection of Partners, Service Providers, Intermediaries

Often projects cooperate with partners such as NGOs, consultants, and public services for project implementation. In this case it is advisable to already collect information on potential partners during the inception study.

Who are the service providers in or near the region experienced in the following:

- Training in production of stoves (technical aspects)?

- Training in good kitchen, stove, and firewood management practices for stove users?

- Advice in business development (to support and train stove producers)?

- Product marketing (to make the stoves known to the public)?

- Awareness raising (to push the demand for stoves)?

For each potential partner/service provider it is useful to know the following:

- Do the service providers have a good approach and reputation (timeliness, accuracy, customer orientation of service provision; corruption; behavior towards customers, partners and donors)?

- Do the providers have the capacity to offer services (or are in the position to increase these capacities if required)?

- Which mode of service delivery do they apply to the target groups (free handout, service for fee, cost sharing, food for work, and cash for work...)?

- What would be the interest of this service provider to cooperate with your program? Does this potential interest support or contradict the aim of the establishment of sustainable markets for efficient stoves?

|

Points to consider:

|

References

This article was originally published by GIZ HERA. It is basically based on experiences, lessons learned and information gathered by GIZ cook stove projects. You can find more information about the authors and experts of the original “Cooking Energy Compendium” in the Imprint.

--> Back to Overview GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium