Difference between revisions of "Mozambique Electricity Situation"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Portuguese Version|Situação_da_Eletricidade_em_Moçambique}} | {{Portuguese Version|Situação_da_Eletricidade_em_Moçambique}} | ||

=Overview= | =Overview= | ||

| − | Mozambique has undertaken significant efforts in recent years to electrify the country. The electrification rate has increased from 5% in 2001 to 24% in 2017, and to 31% in 2020<ref name=":0" />. Access to electricity, however, remains low and is mainly focused on urban areas. In 2020, 75% of the urban population had access to electricity compared to about 5% of the rural population<ref name=":0">World Bank, ‘[https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.UR.ZS?locations=MZ Mozambique | Data]’. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.UR.ZS?locations=MZ</ref>. This imbalance represents an important challenge to achieving country-wide electrification by 2030, considering that the vast majority ( | + | Mozambique has undertaken significant efforts in recent years to electrify the country. The electrification rate has increased from 5% in 2001 to 24% in 2017, and to 31% in 2020<ref name=":0" />. Access to electricity, however, remains low and is mainly focused on urban areas. In 2020, 75% of the urban population had access to electricity compared to about 5% of the rural population<ref name=":0">World Bank, ‘[https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.UR.ZS?locations=MZ Mozambique | Data]’. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.UR.ZS?locations=MZ</ref>. This imbalance represents an important challenge to achieving country-wide electrification by 2030, considering that the vast majority (62% in 2021) of Mozambique’s population lives in rural areas<ref>World Bank, ‘Mozambique | Data’. (2021)https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=MZ</ref>. |

=Electricity Situation= | =Electricity Situation= | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

The total energy production in 2019 was 7,089 GWh. The sources in the mix were 52% from Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB), 35% from other IPPs, 10% thermal (from EDM), 2% other hydro plants from EDM, and 1% of the total generated energy was imported from other countries<ref name=":3" />. | The total energy production in 2019 was 7,089 GWh. The sources in the mix were 52% from Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB), 35% from other IPPs, 10% thermal (from EDM), 2% other hydro plants from EDM, and 1% of the total generated energy was imported from other countries<ref name=":3" />. | ||

| − | In 2021 there were no large changes in the mix, (51% from HCB, 34% from other IPPs, 1% Imported), rather a small shift in the sources of generation from EDM. | + | In 2021 there were no large changes in the mix, (51% from HCB, 34% from other IPPs, 1% Imported), rather a small shift in the sources of generation from EDM. At the end of 2021, only 8% of the generation came from thermal EDM plants, while there was a notable increase in electricity generation from EDM hydro plants<ref name=":9" />. |

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

| − | There are six working hydropower stations across the country<ref name=":1" />. The largest hydroelectric plant is located in the Tete province and is operated by [https://www.hcb.co.mz/ Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB)]. HCB is responsible for most of the hydroelectric generation, with a capacity of 2,075 MW. In 2014, it supplied up to 88% of the power consumed in Mozambique<ref>EDM, Integrated Master Plan 2018-2043,https://www.edm.co.mz/en/document/reports/integrated-master-plan-2018-2043</ref>. HCB supplies about 400 MW to EDM<ref name=":10" />. Due to the low electricity demand (peak demand in 2014 was estimated at only 831 MW) resulting from scarce energy access in Mozambique, the majority of the generation from HCB is exported to South Africa. Smaller shares are exported to Zimbabwe and Botswana<ref name=":1" />. The rest of the hydropower plants are operated by EDM, as shown in the following table. | + | There are six working hydropower stations across the country<ref name=":1">‘Mozambique: Energy and the Poor’, K. Naidoo, C. Loots, 2020, https://sun-connect-news.org/fileadmin/DATEIEN/Dateien/New/2021-01-29_UNDP-UNCDF-Mozambique-Energy-and-the-Poor.pdf.</ref>. The largest hydroelectric plant is located in the Tete province and is operated by [https://www.hcb.co.mz/ Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB)]. HCB is responsible for most of the hydroelectric generation, with a capacity of 2,075 MW. In 2014, it supplied up to 88% of the power consumed in Mozambique<ref>EDM, Integrated Master Plan 2018-2043,https://www.edm.co.mz/en/document/reports/integrated-master-plan-2018-2043</ref>. HCB supplies about 400 MW to EDM<ref name=":10" />. Due to the low electricity demand (peak demand in 2014 was estimated at only 831 MW) resulting from scarce energy access in Mozambique, the majority of the generation from HCB is exported to South Africa. Smaller shares are exported to Zimbabwe and Botswana<ref name=":1" />. The rest of the hydropower plants are operated by EDM, as shown in the following table. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+'''Table: Hydropower installed capacity in Mozambique''' | |+'''Table: Hydropower installed capacity in Mozambique''' | ||

| Line 135: | Line 138: | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ | |+ | ||

| − | '''Table: Mozambique’s key energy indicators''' | + | '''Table: Mozambique’s key energy indicators (2020)''' |

|Energy production | |Energy production | ||

| − | | | + | |745.67 Tj |

|- | |- | ||

| Total primary energy supply | | Total primary energy supply | ||

| − | |10. | + | |10.82 Mtoe |

|- | |- | ||

|Total electricity consumption | |Total electricity consumption | ||

| − | | | + | |12.24 TWh |

|- | |- | ||

|Electricity consumption per capita | |Electricity consumption per capita | ||

| − | |0. | + | |0.4 MWh |

|} | |} | ||

| − | Source: IEA, | + | Source: IEA, 2020<ref name=":4" /> |

| − | Overall, the sector that consumes the most power is industry. In | + | Overall, the sector that consumes the most power is industry. In 2020, the total electricity consumption for industrial activities was 37,353 TJ; the residential sector consumed 5,437 TJ, commercial and public services consumed 134 TJ and agricultural activities 1 TJ. Electricity supplied from the grid, however, is mostly directed to residential users. Based on 2019 billing data from EDM, the on-grid electricity demand in Mozambique is the highest for domestic use (45%) followed by industries (37.3%) and commercial use (16%) <ref name=":4" />. |

In 2021 The total electricity consumption was 3,584 GWh. The most consuming sector is domestic, followed by industry, and commerce<ref name=":9" />. | In 2021 The total electricity consumption was 3,584 GWh. The most consuming sector is domestic, followed by industry, and commerce<ref name=":9" />. | ||

| Line 309: | Line 312: | ||

For a detail insights into the market scoping and potential of off-grid technologies in Mozambique, please refer to the folowing technology portals: | For a detail insights into the market scoping and potential of off-grid technologies in Mozambique, please refer to the folowing technology portals: | ||

| − | *[[Mozambique Solar Hub|Mozambique - Solar Hub]] | + | *[[Mozambique Solar Hub|Mozambique - Solar Hub]] - Information related to solar home systems (SHS) and solar energy in Mozambique |

| − | *[[Mozambique Cooking Energy Hub|Mozambique - Clean Cooking Energy Hub]] | + | *[[Mozambique Cooking Energy Hub|Mozambique - Clean Cooking Energy Hub]] - Information related to clean cooking energy and improved cookstoves in Mozambique |

| − | *[[Mozambique Nano/Mini Grid Hub|Mozambique - Nano/Mini Grid Hub]] | + | *[[Mozambique Nano/Mini Grid Hub|Mozambique - Nano/Mini Grid Hub]] - Information related to nano/mini grids in Mozambique |

| − | *[[Mozambique Productive Uses of Energy Hub|Mozambique - Productive Use of Energy Hub]] | + | *[[Mozambique Productive Uses of Energy Hub|Mozambique - Productive Use of Energy Hub]] - Information related to productive uses of energy in Mozambique |

| + | *[[Mozambique Regulation Hub|Mozambique - Off-grid Energy Regulations Hub]] - Information related to the latest laws, decrees and regulations for off-grid energy | ||

==Further Readings== | ==Further Readings== | ||

Latest revision as of 10:20, 20 June 2023

Overview

Mozambique has undertaken significant efforts in recent years to electrify the country. The electrification rate has increased from 5% in 2001 to 24% in 2017, and to 31% in 2020[1]. Access to electricity, however, remains low and is mainly focused on urban areas. In 2020, 75% of the urban population had access to electricity compared to about 5% of the rural population[1]. This imbalance represents an important challenge to achieving country-wide electrification by 2030, considering that the vast majority (62% in 2021) of Mozambique’s population lives in rural areas[2].

Electricity Situation

In 1977, two years after Mozambique’s independence, State-Owned utility, Electricidade de Moçambique (EDM), was founded. The purpose of EDM was to act as a unification body for the existing generation centres to promote industrial and agricultural development, as well as improve the extension and quality of household electrification. During the first years of operation, EDM functioned with a corporate management based on profit and later changed to a centralised price setting. However, it was not until the economic re-structuring of Mozambique in 1995, when EDM turned into a public company officially known as “EDM-E.P”[3].

The newly reformed EDM is now the responsible entity for generation, transmission and distribution of electricity as well as the regulator of electricity from renewable energy sources, as stated in the Electricity Law (Law No.21/91)[3].

Due to the vital role renewable energy plays in Mozambique’s electrification goal, the Electricity Law has been in constant review since 2017 to ensure technological development and clear tariff mechanisms as well as business models. The most recent update to the law came into force in October 2022 (Law No. 12/2022), which outlines the current state of the legal framework and the roles of participating stakeholders, and it highlights the involvement of the private sector participation and the presence of renewable energies in Mozambique's energy sector[4].

Generation

The total energy production in 2019 was 7,089 GWh. The sources in the mix were 52% from Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB), 35% from other IPPs, 10% thermal (from EDM), 2% other hydro plants from EDM, and 1% of the total generated energy was imported from other countries[5].

In 2021 there were no large changes in the mix, (51% from HCB, 34% from other IPPs, 1% Imported), rather a small shift in the sources of generation from EDM. At the end of 2021, only 8% of the generation came from thermal EDM plants, while there was a notable increase in electricity generation from EDM hydro plants[4].

Table: Electricity generation from RE sources (2019)

| Total electricity production from renewable sources | 7,089 GWh |

| Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa | 3,651 GWh |

| Other IPP | 2,491 GWh |

| Thermal (EDM) | 710 GWh |

| Other Hydro plants | 163 GWh |

| Imports | 74 GWh |

Source: ALER, AMER, with data from EDM[5]

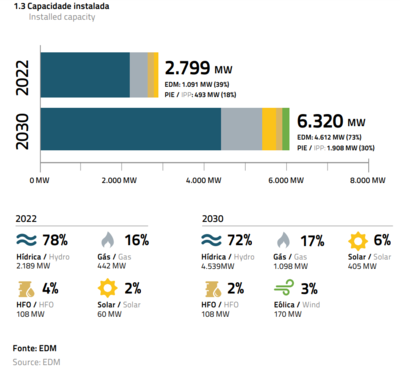

Installed capacity (Renewable sources)

It is estimated that Mozambique reached a total installed capacity of 2,799 MW by the end of 2022, from which 78% corresponds to hydropower, 16% to gas, 4% to heavy fuel oil (HFO), and 2% to solar. The installed capacity corresponds 39% to EDM and 18% to IPP[4]. The projections for 2030 from the Government's Five-Year Plan, show an expected increase in the total installed capacity to 6,320 MW.

Hydropower is the dominating electricity source with 2,189 MW, 78% of the total energy mix, followed by 442 MW from gas (16%), 108 MW from heavy fuel oil (HFO) (4%) and 60 MW from solar (2%) (2022)[4].

The following image shows the current total installed capacity and how much corresponds to each source compared to what the Government's Five-Year Plan forecasts for 2030.

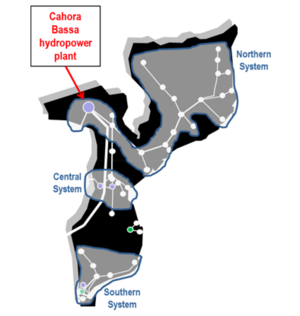

There are six working hydropower stations across the country[6]. The largest hydroelectric plant is located in the Tete province and is operated by Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB). HCB is responsible for most of the hydroelectric generation, with a capacity of 2,075 MW. In 2014, it supplied up to 88% of the power consumed in Mozambique[7]. HCB supplies about 400 MW to EDM[8]. Due to the low electricity demand (peak demand in 2014 was estimated at only 831 MW) resulting from scarce energy access in Mozambique, the majority of the generation from HCB is exported to South Africa. Smaller shares are exported to Zimbabwe and Botswana[6]. The rest of the hydropower plants are operated by EDM, as shown in the following table.

Source: Cahora Bassa Data from 2016[9].

Data for EDM plants from 2018[10]

By 2030, solar plants are expected to provide 266 MW of installed capacity as projected in the Power Sector Master Plan[5]. The latest installed PV-projects have been funded by several international energy programmes and foreign governments, such as the Government of South Korea and the Portuguese Carbon Fund[8] .

In terms of electricity from renewable energy sources, in 2019 Mozambique’s total renewable electricity production was 7,089 GWh. 52% of the total renewable power was generated by the largest independent power producer (IPP): Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa, 35% was generated by other IPP, 12% from EDM’s thermal and hydro plants, and 1% was imported from other countries[5].

As for installed solar capacity, the following table describes the capacity of existing solar plants, and of those under construction and planning.

Table: Capacity from RE sources

| Installed capacity (on-grid) solar | 60 MW |

| Under consturction | 15 MW |

| Signed PPA | 50 MW |

| PROLER tender | 140 MW |

| Pre-feasibility studies | 310 MW |

Source: ALER, AMER, with data from EDM[4]

Transmission and Distribution (Grid Structure)

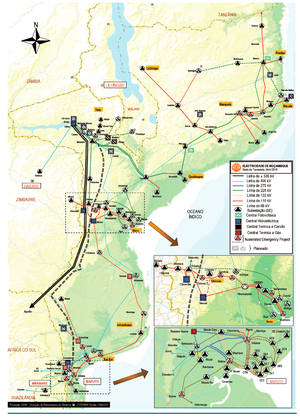

The map below shows the state of the transmission grid across the country in 2016. The provinces of Tete, Sofala and Maputo have the best grid connectivity. In 2016 there were already four substations planned for Beira, three for Maputo, and more spread throughout Mozambique. The southern grid network is not currently connected to the north and central networks; instead, the inter-connector with South Africa is used to power the city of Maputo. Thus, the majority of the electricity generated in the North is exported to South Africa and then re-imported[11].

The national grid has two isolated power components:

- Northern-central: 220 kV transmission lines from Songo to Nampula and then continuing at 110 kV to Nacala. 110 kV transmission lines from Chicamba and Mavuzi hydropower plants to Beira- Manica corridor.

- Southern: 110 kV transmission lines from Maputo to XaiXai, Chokwe and Inhambane[12].

The Mozambican Government is also planning a major transmission project called, Mozambican Integrated Transmission Backbone System (STE). This project will interconnect the isolated power systems and link Tete and Maputo province with extra high voltage transmission lines. Phase 1 of the project includes a 400 KV line connecting Vilanculos with Maputo and three new sub-stations in Vilanculos, Chibuto and Matalane[13] and was planned to commence in late 2021[14]. On April 2022, the Government of Mozambique announced the new grid interconnection lines between Malawi and Mozambique. This 440 kV transmission lines will supply 50 MW of power to Malawi and included 142 km of transmission lines, 527 high voltage pylons and a sub-station at Matambo to ensure grid reliability.[15]

The African Development Bank also approved a grant in Sep 2021 to construct and operate a new National Control Centre for connecting upto 150 substations above 66 kV in Mozambique. This control center help to increase the grid stability, integrate higher share of renewable energy into the grid and to export power with other countries via the Southern Africa Power Pool (SAPP). Implemented by EDM, the project is part of the Mozambique Energy for All programme.[16]

Electricity Consumption

The table below shows the most recent energy indicators reported by the IEA. In 2018, the total primary energy supply was 10.43 Mtoe, from a total of 20.23 Mtoe produced that year. Final electricity consumption was only 13.63 TWh, however, this number has increased drastically by more than 2000% since 1990[17].

| Energy production | 745.67 Tj |

| Total primary energy supply | 10.82 Mtoe |

| Total electricity consumption | 12.24 TWh |

| Electricity consumption per capita | 0.4 MWh |

Source: IEA, 2020[17]

Overall, the sector that consumes the most power is industry. In 2020, the total electricity consumption for industrial activities was 37,353 TJ; the residential sector consumed 5,437 TJ, commercial and public services consumed 134 TJ and agricultural activities 1 TJ. Electricity supplied from the grid, however, is mostly directed to residential users. Based on 2019 billing data from EDM, the on-grid electricity demand in Mozambique is the highest for domestic use (45%) followed by industries (37.3%) and commercial use (16%) [17].

In 2021 The total electricity consumption was 3,584 GWh. The most consuming sector is domestic, followed by industry, and commerce[4].

| Domestic | 44.9% |

| Industrial | 37.5% |

| Commercial | 15.0% |

| Agriculture | 0.9% |

| Public Lighting | 1.4% |

| EDM Consumption | 0.2% |

Source: ALER, AMER, with data from EDM[17]

Electricity Tariffs

EDM offers different tariff options. The following table shows the current prices (in MZN/kWh) for low voltage use for households and smallholder farmers. These tariffs are uniform across the country [18].

| Recorded Consumption (kWh) | Sale Price | Flat Rate (Mt/kWh) | |||

| Social Tariff (Mt/kWh) | Household Tariff (Mt/kWh) | Farming Tariff (Mt/kWh) | General Tariff (Mt/kWh) | ||

| From 0 to 100 | 0.97 | ||||

| From 0 to 200 | 6.00 | 3.69 | 9.32 | 233.37 | |

| From 201 to 500 | 8.49 | 5.26 | 13.31 | 233.37 | |

| Above a 500 | 8.91 | 5.75 | 14.56 | 233.37 | |

| Pre-Payment | 0.97 | 7.64 | 5.11 | 13.34 | |

One of the billing methods offered to EDM customers is through conventional electric meters. These meters are lent to the users and read monthly by trained EDM employees to calculate the user’s monthly electricity consumption. Customers may pay their electricity bill directly by bank deposits either by filling up an invoice inside the bank, by money transfer at the bank’s ATM, or as an automatic debit from their payroll accounts[19] .

Another alternative is the use of a pre-paid system called CREDELEC. This system allows users to have control over how much they want to spend in a specific time period by not being forced to pay a monthly fee. This avoids the risk of sudden disconnection due to lack of payment. Purchase options for pre-paid CREDELEC include scratch cards that are available in convenience stores, supermarkets, or by paying directly at EDM ATMs. In 2020, about 78% of electric energy consumers (more than 671,322 clients) got billed through the CREDELEC system[19].

The following table shows the current tariffs (in MZN/kWh) for major consumers for commercial and agricultural activities.

| Class of Consumers | Sale Price | Flat Rate (Mt) | |

| (Mt/kWh) | (Mt/kW) | ||

| Major Consumers of Low Voltage | 5.74 | 441.12 | 683.29 |

| Medium Voltage | 4.78 | 497.03 | 3,207.25 |

| Medium Voltage (Agricultural) | 2.72 | 313.29 | 3,207.25 |

| High Voltage | 4.70 | 600.10 | 3,207.25 |

Source: Data from EDM[18]

Over the past decade, EDM has been working on restructuring finances to reach a cost-reflective tariff system. In an attempt to lessen the debt and insolvency the company faces, there has been significant tariff increases, which have made it unaffordable for many electricity users to pay their bills. This reality has forced EDM to subsidise tariffs for poor households who are unable to pay, in order to keep them as customers, but at the same time sacrificing the company’s sustainability by keeping operation at a loss. It is estimated that EDM provides subsidies in the form of discounts of about 84% of the monthly electricity bill to most of their retail customers[6] .

As a measure to drive private investments in the energy sector, Independent Power Producers (IPP) were introduced in 2015. However, without a strong financial framework and clear business models, IPPs are expected to face the same fate as EDM and will be compelled to look for other forms of international funding[6].

Power Shortage/Load-shedding

The electricity service suffers from a circular problem. While electricity demand in Mozambique appears low, it is at an increase especially considering the projected growth in population. The IEA projects a primary energy demand of over 20 Mtoe by 2030 according to current stated policies, and a total population of 43 million by 2030 and 55 million by 2040. These factors result in electricity demand exceeding the share of electricity generated that is not for export, affecting business with South Africa and other countries[20]. Additionally, losses of 27% of the generated power, due to limited available technical staff and delays in the maintenance of the grid aggravate the already insufficient power supply[5]. As a measure to improve the conditions of the grid, EDM has programmed a series of scheduled outrages in 2018 for maintenance of the power system[21].

Access to the Grid / Grid Densification

Access to electricity provided by EDM has increased from 8% in 2006 to 31% in 2018, which translates into more than 1.89 million customers[22]. At the end of 2020, on-grid electrification rate increased to 34%[5], and in the end of 2021 it reached 40.8%[4]. However, grid connection is mostly concentrated in urban areas and scarce in poor rural communities. Geographically, Southern provinces close to Maputo Cidade i.e Maputo (62%), Gaza (40%), Sofala (37%) and Manica (34%) have higher electrification rate compared to northern provinces such as Tete (26%), Cabo Delgado (26%), Nampula (25%), Zambezai (18%) and Niassa (17%). Overall, Maputo city has the highest electrification rate of 95% (based on Finscope survey 2019)[23].

Despite living within the reach of the national grid, many Mozambicans do not have access to it due to the high connection fee. EnDev Mozambique has supported EDM with its grid densification programme and this effort made it possible for the Government of Mozambique to waive the connection fees in Dec 2020[24]. Nevertheless, extending the national grid to the rural remote communities is not a viable business solution as it requires large investment and the rural communities are not able to pay a tariff that can cover up this investment cost[25].

The table below summarises the ongoing grid densification projects in Mozambique (until 2022).

| Programme | Target | Timeframe | Donor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mozambique Energy for All (MEFA) | 48,955 new connections

(Nampula: 26,455 new connections and Zambezia 22,500 new connections) |

2022-2025 | African Development Bank[26] |

| Mozambique Energy for All (ProEnergy) | 250,000 households

(185,000 are in rural areas and 65,000 in peri-urban areas) |

2019-2025 | World Bank[27] |

Rural Electrification

Mozambique’s Fundo de Energia (FUNAE), is the public institution responsible for off-grid rural electrification with a special focus on renewable energy. Since its foundation in 1997 with monetary support from EDM, FUNAE has provided access to electricity to 580 schools and 561 health centres in 260 villages who previously relied on either kerosene or candles for lighting[22]. In 2020, about 5% of the total rural population had access to electricity[1]. However, since more than half of Mozambique’s population lives in rural communities, this increase is still low, posing a challenge to achieve the goal of electrifying all Mozambican households by 2030.

A major obstacle to the expansion of rural electrification is the lack of sustainability in FUNAE’s income. The cost of electrification programmes is not covered by EDM’s tariffs, due to electricity users not being able to afford them, even though the tariffs are highly subsidised and potential clients live within the reach of the grid. Since EDM does not receive any subsidies from the government to fund to sustain FUNAE’s electrification projects, FUNAE has to rely on external investments and donations to keep operating[22].

For detail information about the energy access situation (both on and off grid), rural electrification plan, access to energy for cooking please refer to the article on Energy Access in Mozambique.

For detail information about the different energy access programmes in Mozambique, please refer to the article on Energy Access Programmes in Mozambique.

Off-grid Market Situation Overview

For a detail insights into the market scoping and potential of off-grid technologies in Mozambique, please refer to the folowing technology portals:

- Mozambique - Solar Hub - Information related to solar home systems (SHS) and solar energy in Mozambique

- Mozambique - Clean Cooking Energy Hub - Information related to clean cooking energy and improved cookstoves in Mozambique

- Mozambique - Nano/Mini Grid Hub - Information related to nano/mini grids in Mozambique

- Mozambique - Productive Use of Energy Hub - Information related to productive uses of energy in Mozambique

- Mozambique - Off-grid Energy Regulations Hub - Information related to the latest laws, decrees and regulations for off-grid energy

Further Readings

- Energy Access in Mozambique

- Policy Framework & Energy Access Strategies in Mozambique

- Energy Access Programmes in Mozambique

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 World Bank, ‘Mozambique | Data’. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.UR.ZS?locations=MZ

- ↑ World Bank, ‘Mozambique | Data’. (2021)https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=MZ

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 EDM, ‘Legislation | EDM - Electricidade de Moçambique, https://www.edm.co.mz/en/website/page/legislation

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 ALER, AMER 2022, Briefing: Renewables in Mozambique, https://mocambique.lerenovaveis.org/contents/lerpublication/a4_resumo_renov_moz_2022_vfinal.pdf

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Aler_mar2021_resumo-Renovaveis-Em-Mocambique-2021.Pdf’, accessed 23 April 2021, https://www.lerenovaveis.org/contents/lerpublication/aler_mar2021_resumo-renovaveis-em-mocambique-2021.pdf

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 ‘Mozambique: Energy and the Poor’, K. Naidoo, C. Loots, 2020, https://sun-connect-news.org/fileadmin/DATEIEN/Dateien/New/2021-01-29_UNDP-UNCDF-Mozambique-Energy-and-the-Poor.pdf.

- ↑ EDM, Integrated Master Plan 2018-2043,https://www.edm.co.mz/en/document/reports/integrated-master-plan-2018-2043

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 GET.invest, ‘Renewable Energy Potential, https://www.get-invest.eu/market-information/mozambique/renewable-energy-potential/

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 IHA, Hydropower Status Report, https://www.lerenovaveis.org/contents/lerpublication/iha_2016_may_hydropower-status-report-2016.pdf

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 EDM, ‘Generation | EDM - Electricidade de Moçambique, https://www.edm.co.mz/en/website/page/generation

- ↑ SEforALL Africa Hub, AfDB, Mini Grid Market Opportunity Assessment, https://www.aler-renovaveis.org/contents/lerpublication/afdb_2017_abr_mini-grid-market-opportunity-assessment-mozambique.pdf

- ↑ Goodrich, G., Mozambique: A Regional Electricity Exporter | Energy Capital & Power, https://energycapitalpower.com/2020/10/09/mozambique-a-regional-electricity-exporter/

- ↑ AfDB, ‘Mozambique-Temane Transmission_Project , Mozambique Integrated Transmission Backbone System (STE_Project), Phase 1- Vilanculos – Maputo – ESIA Summary, https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Environmental-and-Social-Assessments/Mozambique_-_Temane_Transmission_Project_Mozambique_Integrated_Transmission_Backbone_System__STE_Project___Phase_1-_Vilanculos_%E2%80%93_Maputo_%E2%80%93_ESIA_Summary.pdf

- ↑ Power Africa, ‘Linking Electricity to Economic Growth and Energy Security, https://powerafrica.medium.com/linking-electricity-to-economic-growth-and-energy-security-mozambiques-temane-transmission-e47fe6936f07

- ↑ Mozambique and Malawi commence electricity interconnection project: https://www.esi-africa.com/mozambique-and-malawi-commence-electricity-interconnection-project/

- ↑ African Development Bank (2021). Mozambique Energy for ALL (MEFA) - Project Appraisal Report. https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/mozambique-mozambique-energy-all-mefa-project-appraisal-report

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 IEA, ‘Mozambique - Countries & Regions’ https://www.iea.org/countries/mozambique

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 18.2 EDM, ‘Electricity Tariffs | EDM - Electricidade de Moçambique, https://www.edm.co.mz/en/website/page/electricity-tariffs

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 EDM, ‘Contador CREDELEC | EDM - Electricidade de Moçambique, https://www.edm.co.mz/en/products/contador-credelec

- ↑ IEA, Africa Energy Outlook 2019, https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2019

- ↑ EDM, ‘Scheduled Outages | EDM - Electricidade de Moçambique, https://www.edm.co.mz/en/website/page/scheduled-outages

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 22.2 World Bank, Mozambique Energy for All ProEnergia Project, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/594061554084119829/pdf/Mozambique-Energy-for-All-ProEnergia-Project.pdf

- ↑ Finscope, ‘Mozambique: Finscope Consumer Survey Report 2019, https://finmark.org.za/system/documents/files/000/000/155/original/Mozambique_Survey-2020-07-311.pdf?1597303567

- ↑ Green Building Africa, Domestic Connection Fees Abolished in Mozambique, https://www.greenbuildingafrica.co.za/domestic-connection-fees-abolished-in-mozambique/

- ↑ EDM, ‘EDM Strategy 2018-2020’, https://www.edm.co.mz/sites/default/files/documents/Reports/EDM_STRATEGY_2018_2028.pdf

- ↑ African Development Bank (2021). Mozambique Energy for ALL (MEFA) - Project Appraisal Report. https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/mozambique-mozambique-energy-all-mefa-project-appraisal-report

- ↑ Mozambique-Energy-for-All-ProEnergia-Project.Pdf’, accessed 26 May 2021, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/594061554084119829/pdf/Mozambique-Energy-for-All-ProEnergia-Project.pdf