Air Quality Management And Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions

Approximately 6 million premature deaths occur annually due to air pollution, making it a major global health risk and top priority for international as well as national health and environmental politics. The main culprit for those deaths are small particles, especially particulate matter with a diameter of 10 μm (PM10) or even the smaller particulate matter with diameter of 2.5 μm (PM2.5). PM2.5 consists of different ingredients, with one of the most important ones being black carbon (BC). 55-65% of anthropogenic BC emissions are generated mainly by industry and transport through the incomplete burning of fossil fuels.

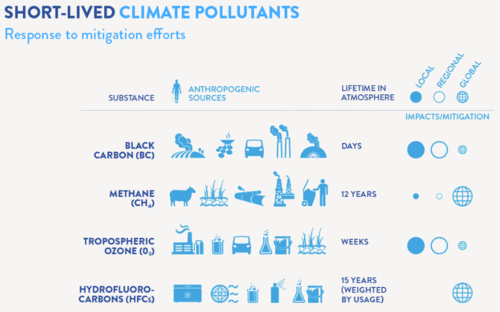

BC is a Short Lived Climate Pollutant (SLCP). Besides BC, the most common SLCPs are hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), tropospheric ozone (O3) and methane (CH4). SLCPs are responsible for approx. 40% of global warming[1]. They not only contribute to global warming and cause premature deaths, but also promote chronic diseases, e.g. acute respiratory infections or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Premature birth most likely is also related to air pollution[2], and it can hinder the effectiveness of antibiotics and medication[3]. SLCPs also damage plants, reducing their photosynthesis and CO2 absorption capacity, exacerbating hereby global warming and affecting agricultural yields. Reducing SLCPs therefore has positive effects on public health and on global warming alike. Reducing CH4 and BC alone can lower global warming by approx. 0.5°C until 2050[4]. Yet, since SLCPs are short lived in the atmosphere, their reduction has to go hand in hand with CO2 reduction to have lasting effect. Luckily, some strategies to reduce SLCPs serve also to reduce CO2 levels, e.g. regulations on fuel, phasing out coal burning etc.

Air Pollution in Lower and Middle Income Countries

Especially affected by air pollution are Lower and Middle Income Countries (LMIC). According to the World Bank, about 95% of adults and children impacted by pollution-related illnesses live in those countries. Those numbers show two things: the urgency to proactively address air pollution and the inability to do it effectively until now. Political arrangements, institutional settings, funds to tackle air pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as well as knowledge about the impact of air pollution, its relation with GHG emissions and ways to counter it are insufficient and have to be addressed in most of those countries. This is due both to insufficient capacities as well as political will. While generally PM10 -as one of the causes of deaths and illnesses due to air pollution- is considered in many countries' legal frameworks, the even more harmful PM2.5 is not. In other LMICs' national air quality standards, related regulations and monitoring systems are missing altogether. The World Health Organization (WHO) stated in 2016: "In general, urban air pollution levels were lowest in high-income countries, with lower levels most prevalent in Europe, the Americas, and the Western Pacific Region. The highest urban air pollution levels were experienced in low- and middle-income countries with annual mean levels often exceeding 5-10 times WHO limits, followed by low-income cities. In the African Region, urban air pollution data remain relatively sparse, however available data revealed particulate matter (PM) levels above the median[5].

The project “Integrated Air Quality Management and Climate Change Mitigation”

Only an integrated framework that tackles air pollution in the wider context of GHG emissions will be effective in the long term. Erecting moss walls, greening a city or implementing filter solutions to factories or vehicles, while all somehow effective and desirable, do not have the same profound effect like avoiding the pollution in the first place. An air quality management (AQM) plan that considers air pollution as climate related will therefore usually be better suited to improve air quality.

The project "Integrated Air Quality Management and Climate Change Mitigation", funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) and implemented by GIZ strives to bring about integrated planning as well as effective short term actions on air pollution and GHG emissions reduction. The project exemplarily works in three megacities: Pretoria (Tshwane) and Johannesburg in South Africa, and Hanoi in Vietnam. Each one is struggling with major air pollution. The project assists the administrations of the three cities in implementing effective AQM plans and concrete measures, which should lead to the improvement of their air quality.

The City of Tshwane in South Africa

The City of Tshwane in South Africa has a dedicated AQM unit. GIZ currently assists them in the review of their AQM plan, a document that is valid for five years, ideally guiding during that time all the efforts the city undertakes to improve its air. And this is Tshwane's vision: "Ambient air in the City of Tshwane is clean and healthy for all citizens through effective and collaborative management that ensures compliance and sustainable development".

While there may be divergent views on what "sustainable development" exactly means, a "clean and healthy air is clearly defined as an ambient air quality that complies with the health-based National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)". Thus, the guiding framework for any activity or policy on air quality is NAAQS. In order to put South African air quality standards into perspective, it is worth comparing them with WHO and European guidelines.

Standards: Comparison of South African NAAQS and WHO standards

| Pollutant | South Africa NAAQS | WHO | European Union Air Quality Directive |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 |

|

|

|

| PM10 |

|

|

|

| O3 (Ozone) |

|

|

|

| NO2 (Nitrogen dioxide) |

|

|

|

| SO2 (Sulphur dioxide) |

|

|

None |

Generally, South African standards allow for more legal air pollution than the WHO ones.

So, what does Tshwane plan to do to achieve better air quality? A first basic step and at the same time part of the implementation of AQM measures already is stakeholder participation. This is an essential ingredients well for the German Development Cooperation: Only when constantly in touch with the public can the city communicate the state of the air, identify needs, fears and demands and translate them into a sound plan and actions. Part of the outreach to the public (not only by Tshwane but nationally and all its cities) is the South African Air Quality Information System. Here, citizens can not only see real time air pollution indices for different locations but as well review literature and legal documents.

Air Pollution in Tshwane has several causes: Heavy traffic combined with low fuel standards, a lot of cooking and heating with coal and wood (including small boilers) (see also Indoor Air Pollution (IAP)), informal burning of waste, industrial activities like e.g. mining. This is insofar important as it describes responsibilities: public as well as private and business responsibilities with the lead and overall coordination of the efforts in the hands of the city.

Strategies to Improve Air Quality

The AQM plan of Tshwane details several strategies to improve air quality of which only some will be highlighted here:

- Tackle air pollution (most of all particulate matter) in high-density low-income residential areas where wood and coal still are the preferred energy option. This will be done by forging partnerships to provide cost-effective and sustainable clean energy alternatives to residents; by identifying and implementing clean-technology combustion devices; by promoting the co-benefits for air quality and health of energy-efficient houses. The GIZ will assist the City of Tshwane e.g. by checking feasibility of introducing renewable energy off-grid solutions to mentioned areas or introducing compressed liquid gas production from organic waste. This is accompanied by awareness raising work for the wider public.

- Address emissions from motor vehicles, e.g. by improving public transport, restricting vehicles in high traffic zones, provision of alternative non-car infrastructure. However, improving air pollution from traffic is a very hard task and needs piecemeal introduction. Part of this is awareness raising and induction of changes at the city level itself (different budget allocations, road planning, transport planning etc.). Roadside testing of vehicle emissions is another way to improve awareness and accompany the introduction of more stringent rules and standards. However, security is an issue - not everybody is willing to forgo his/her car and instead walk or cycle due to fears about potential attackers on the street.

- Reduce NOx emissions from small boilers. This starts with a proper stocktaking of small boilers. The form that has to be filled out to comply with the regulation to register boilers is still very complicated and could be simplified a lot. This would help compliance and inventory which is a cornerstone for effective regulation. Likewise, important is the enforcement of the regulations for small boilers including emission testing and reporting.

- Reduce informal burning of waste. Around 159,000 households (out of 906,000) are assumed to burn their waste due to inadequate waste collection. This makes burning a major emission sector in Tshwane, contributing considerably to emissions of particulates among others. The GIZ will assist the city of Tshwane in addressing this problem by checking feasibility of organic waste collection and turning it to compressed liquid gas (see point 1 above)

There are other emission sources like agricultural burning or mining close to the city, but those do have minor climate impacts (even if they pollute the air substantially).

A necessary condition for meaningful strategies for air quality improvement is to know the emissions, monitor their development and thereby be able to develop effective strategies (Are we focusing on the important emitters? Is what we are doing having an effect?). Therefore, the city of Tshwane needs a working monitoring network, which is why GIZ assistance is geared towards building up and maintaining their monitoring network as well. Planning, action and monitoring are different aspects of the same big task: improving the air while at the same time reducing GHG emissions!

Further Information

- Monitoring AQM: Air Quality Index (AQI) - Hanoiand Hanoi Air Quality Monitoring and South African Air Quality information System - SAAQIS

- Portal Mobility

- Climate Change and Transport

- Air Pollution in Hanoi, Vietnam

- Economic Costs of Air Pollution

- Enviromental Impacts

- Low Carbon Transport & Green Growth

- Climate Change and Transport

- Assessing Climate Finance for Sustainable Transport

- Resilience in the Transport Sector

- Promoting Rural Development through Mobility

- International Fuel Prices

- Cooking with Coal

- Cooking with Firewood

References

- ↑ Cf. http://www.igsd.org/documents/PrimeronShort-LivedClimatePollutants.pdf or http://www.iass-potsdam.de/sites/default/files/files/kurzlebige_klimawirksame_schadstoffe_0.pdf

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/feb/16/premature-births-air-pollution-maternal-health-who-study

- ↑ https://www.iol.co.za/mercury/environment/air-pollution-study-shock-8791974

- ↑ http://www.iass-potsdam.de/sites/default/files/files/kurzlebige_klimawirksame_schadstoffe.pdf

- ↑ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2016/air-pollution-rising/en/